For twenty years I wired my parents five thousand dollars a month for my sister’s treatment, lived on ramen to “save” her, flew home to surprise them, and found a mansion, new cars, and Marlene perfectly healthy on the porch laughing, “The loser believed it.” My father barked the line like a punchline, my mother smirked, my sister lifted her phone to make it viral, and I walked away without an argument because something colder than rage had already started to assemble. The next morning, they began losing everything—accounts frozen, loans called, a foreclosure notice stapled to the dream I had funded. Eviction arrived like winter at the door, and the neighborhood watched the moving truck swallow their pride one room at a time. That was later; before the collapse there were two decades of little screens and big sacrifices. There was a decade-old laptop flickering in a cold Chicago studio, a radiator that coughed instead of heating, and a wife who learned to sleep in layers. Another transfer went through, Joanna whispered, and I closed the computer on a life we had put on hold for someone else’s lie.

I was twenty-three when it started and forty-three now, a thousand month-ends stitched into one long apology to the people who raised me. By day I was a data analyst; by night I loaded pallets in a warehouse while Joanna pulled double shifts at the hospital and never once complained. She didn’t complain when we postponed a honeymoon indefinitely, or when we decided we couldn’t afford children, or when her nursing friends waved from porches in suburbs we would never afford. She patched holes in our rental with dollar-store spackle and told me she’d “signed up for me,” which was both a blessing and a weight. The script about Marlene never changed—mysterious autoimmune disorder, complications, maybe an experimental therapy next month if we hurried. Every plea slid into my ear with my father’s sturdy authority and my mother’s tears braided through the line like barbed wire wrapped in lace. Family was everything; they had taught me that, and I had tried to make the equation true with money.

Joanna asked the question we both knew was radioactive: in twenty years, had I seen Marlene once, even through a hospital window. There was always a reason to keep me away—too weak for visitors, in isolation, the facility prohibiting outside contact during “critical phases.” My father “sent updates,” which sounded more hollow each time the word left my mouth and failed to change the air. No photos, no video calls, no footprints except invoices and urgency, and the late-night doubts crept in like drafts under the door. I would crush them with guilt and tell myself good sons don’t question dying sisters; good sons don’t audit their parents. “He’s from another generation,” I said, as if that explained the absence of proof in a world where everything leaves a trail. Still, the seed once planted threw out roots because that’s what seeds do when you water them with hunger.

I built our life like an austerity budget turned into religion, made every dollar scream before I let it go, and learned to cut my own hair by YouTube light. Clothes came from thrift stores, the car died five years ago and stayed dead, and the Chicago transit map became our family tree. At work Warren Richardson, my manager and one of my few friends, told me I was the best analyst he’d ever seen and the most exhausted man he knew. He told me about counseling; I told him I was “just focused,” because vacations cost money and money belonged to a diagnosis that did not exist. On the bus one night, I called my father and said I was coming home that weekend, and the silence on the line had a temperature. “Not a good time,” he tried, “critical phase,” he said, but I said I wanted to see them, not the hospital. He agreed in a voice that reminded me guilt is a lever if you have the right fulcrum.

Ohio in late spring is green enough to break your heart if you let it, and the rental car rolled past fields that remembered me better than my parents did. The farmhouse on Maple Ridge should have been there like a sentence I could recite in my sleep, but a SOLD sign stood in a vacant lot where our porch once held summer. GPS took us through a neighborhood I didn’t recognize—brick facades, manicured hedges, circular drives, and the hum of engines that cost more than our lives. “Arrived,” the screen announced as we faced a three-story mansion with a silver Mercedes and a black BMW idling like guard dogs. On the porch swing, a woman in designer athleisure scrolled a phone and looked up with skin that glowed and a smile that cut. “Mom, Dad, the loser’s here,” she called, and my father came out in a polo and Rolex while my mother’s hair caught the light like a secret she would never share with me. My sister was not dying; she was thriving on the stipend I mistook for love.

“What is this,” I asked, and they laughed as if I had told a joke at my own expense. “You paid for all of it,” my mother said sweetly, and my father spread his arms to encompass the house, the cars, the European vacations, and Yale—“we chipped in about twenty percent.” There had never been an illness, my sister snorted, “you idiot,” and explained how the lie started to cover tuition and grew because easy things often do. “You should thank us,” my father said, rings flashing as his hand clapped my shoulder, “we taught you sacrifice, hard work, made a man out of you.” “The loser believed it,” he crowed, delighted by his own line, and my sister filmed my face for her followers. I stood still because something inside me had gone very quiet and very precise, the way it does before a cut that matters. “I need to go,” I said, and they were almost disappointed I didn’t give them the performance cruelty wants.

I drove ten minutes without speaking and pulled into a rest stop where semis mauled the air and the asphalt glittered with old spills. Only then did the grief hit with the full weight of its details—twenty years of thin dinners, Joanna’s tired hands, the cold apartment, the not-yet children, all of it collected like interest on a predatory loan. Under the pain, a different engine turned over, the one that runs on pattern recognition and the cold math of correction. Joanna’s hand found mine and asked what I would do, because love is both a heart and a calendar. I opened my phone and began a list the way I always begin: variables, resources, constraints, outcomes. “I’m going to think,” I said, “and then I’m going to act,” and she nodded because that is how you end a chapter without throwing the book.

Back in Chicago I stacked twenty years of bank statements on the kitchen table and called Warren, who came without questions because he had eyes. “My family defrauded me for two decades,” I said, and laid the facts out like data because the truth is always clearest in rows and columns. I sent 1.2 million dollars to a lie; I wanted it back and I wanted them to understand exactly what they had done. Warren read the plan I had drafted at four in the morning and said parts of it were “possibly illegal,” and I said “possibly effective,” and we found the legal spine to hold the weight. Public records put a price tag on the dream—1.8 million for the house, mortgage in my father’s name, and four hundred thousand I had wired that year for “emergencies.” My father’s LLC “Thompson Luxury Consulting” had no clients until you looked at the shells that led to other shells that led to my money; tax fraud sprawled like ivy across a fence. My sister’s social media supplied the rest—Gucci “bought by Christian’s treatment fund,” Paris gratitude for “big bro the sucker,” and dinners that tasted like contempt on camera.

Six months earlier, a crack had appeared in the story when my father asked for fifty thousand for a Cleveland specialist and I quietly called every autoimmune specialist in the city. There were twelve; none had heard of Marlene, and something inside me adjusted a dial I should have touched years ago. Ohio is a one-party consent state, so I recorded calls, saved texts, and hired a private investigator to photograph the facts my parents had refused to show me. The law offered a lever labeled fraudulent inducement; triple damages glittered on the end of it if I wanted to pull. But lawsuits take time and time is debt, so I built a parallel track where institutions do the lifting: IRS, lenders, employers, and the court of public record. Monday morning I filed a detailed complaint with the IRS Criminal Investigation division, and that same afternoon I filed a civil suit against Arnold, Dorothy, and Marlene for fraud, seeking the full amount plus interest. By nightfall I had contacted the three “clients” of my father’s LLC; two had never heard of him and the third was my uncle Clayton’s company, a laundering loop I closed with a cease-and-desist and a promise to add him as a co-conspirator if he didn’t cooperate.

The phone lit up like a switchboard in a movie—my father bellowing “we’re family,” my mother sobbing “misunderstanding,” my sister screeching “you bastard, they fired me,” and I answered each with the same sentence. I am collecting what you stole; family doesn’t do what you did; this isn’t revenge, it’s accounting, I am balancing the books. The IRS opened a formal case by Thursday, the banks called the loans by Friday, and Warren stopped by my cubicle to tell me the foreclosure had posted. It felt like watching a particularly clean regression confirm a messy hypothesis; the dominoes fell in the order I had mapped. I slept for the first time in years, not because I had won, but because physics had finally reported for duty.

The prosecutor from Fairfield County called to say the case could support charges—tax evasion, wire fraud, money laundering—and asked if I’d testify. Clayton, my father’s brother, asked me to dinner and told me a story about his son Marcus, leukemia real and remission hidden, three years of “experimental treatments” he had paid for while Arnold pocketed the money. He hadn’t reported it because shame is the quietest jail, and he told me not to make the same mistake with mercy. At deposition my father sat small in a cheap suit and admitted under oath there had been no illness, no treatment, and 1.2 million spent on a house, cars, trips, and tuition. “We wanted a better life,” he said, and when Blake asked if he had ever inquired whether I could afford his better life, he said no. “I’m sorry, son,” he said, and I told him he was sorry he got caught, because precision is cruel and fair. The motel where they lived after foreclosure smelled like mildew and microwaves, and I visited once because Joanna told me choices land harder when you see the ground.

They tried to settle; I offered terms that were not a pyre but a mirror—two hundred thousand up front, fifty thousand a year for twenty years under court supervision, wage verification, garnishment for all three, and a public apology on every platform my sister used to mock me. “You’re making them live your life,” Blake said, and I said that was the lesson they had insisted I learn. They accepted because evidence is a trap for people who make a sport of denial, and the apology video went viral for all the reasons my sister expected, just inverted. The first wire hit—two hundred thousand dollars in our account—and Joanna and I stood over the screen crying because relief has its own weather. We moved into a modest house with heat that worked, bought a couch that didn’t come with someone else’s story, and slept without wearing coats. I read the quarterly reports like any other file—my father mopping a warehouse at night, my mother on a grocery register, my sister at a call center—and felt complicated things that were not regret.

A year in, Marlene mailed a letter on lined paper about court-ordered therapy that had become voluntary, shame that had become a lens, and the cruelty she could not explain except as an attempt to make me small enough to justify theft. I put it in a drawer with the settlement and didn’t answer, but late at night I thought about sixteen-year-old Marlene, a story put in her mouth by a father who liked the way power sounded. We decided to try for a baby and learned the economics of hope, and after months and IVF and forty thousand dollars we met joy without qualifiers. When my mother died, my father asked the court to modify payments, and I agreed on the condition he send me a letter that told the truth. He wrote about jealousy and mediocrity, about the addictive hit of control each month my transfer arrived, about the day on the porch when he saw the real me instead of the son in his story. “I loved you and I destroyed you,” he wrote, “and those two things are not contradictions when love is selfish, cruel, and broken.” I understood without forgiving, which is a grown-up kind of mercy that tastes like work.

Our son Warren was born and we named him after the friend who stood beside me when I had nothing left, and I realized I did not want to be a father who ran on revenge. At three in the morning I called Blake and asked him to draft an early-termination option—one last lump sum they could realistically scrape together, then no more garnishments, no more reports, no more looking over their shoulders or mine. Two months later they sent seventy-five thousand dollars; I deposited it and felt the last piece of armor slide off. The internet stopped searching our names, the mail stopped carrying threats, and the house felt like a place instead of a plan. We found a rhythm that sounded like meals, bedtimes, paydays, and the soft click of a door locking from the inside because you live there. Some people called it weakness; I called it enough.

Five years later a nervous twenty-five-year-old named Joshua Spence—my cousin—walked into my office with a cheap suit, a folder, and a question about my father’s sudden interest in his mother’s Alzheimer’s care. The pattern glowed under the surface—medical crisis, power of attorney, “coordinating” information, and the pre-work for a fundraiser that would run through my father’s accounts first. I told Joshua how to verify everything without my father in the middle, to document every conversation, and to understand that an addict’s apology is not a cure, it is a symptom. Then I called Clayton, who hired a PI and an elder-law attorney; we revoked the POA, got a professional guardian appointed, and arranged care that did not require my father’s permission to be decent. He called to say he had changed, and I said maybe, but change doesn’t obligate trust, and this time there would be no victim apprenticeship on my watch. Months later Marlene phoned to say my father was dying of pancreatic cancer, and I had an oncologist friend read the charts because verification is respect for both truth and memory. Joanna told me to go “for me, not for him,” and I did, and in a hospice room that smelled like decency my father told the truth I had already learned without his help.

“I forgive you,” I said, not because he deserved it, but because I refused to carry him into the rest of my life like a suitcase packed by a thief. Forgiveness didn’t rewrite the ledger or erase the interest; it put down the weight I could no longer justify bearing. He asked if I would come back, and I said I didn’t know, and I told him I hoped he found peace, and I left. Six weeks later he died; I didn’t attend the funeral, but I sent flowers with a note that read, simply, Rest in peace. Years passed the way good years do—Warren grew, Emma arrived, Joanna tended a small garden, and I became the kind of leader who remembers what scarcity feels like and refuses to manage by it. Sometimes Marlene sends a holiday card from a life she is building as a nurse who earns what she has, and sometimes I feel hope instead of heat when I see her name. One night I opened the drawer with the lawsuit, the settlement, the letters, the quarterly reports—the paper trail of betrayal and balance—and fed it all to a shredder that hummed like a benediction.

Warren asked about a grandfather he never met, and I told him people can teach good lessons with bad lives if you have the wisdom to take what’s useful and reject what’s toxic. Joshua wrote to say he tells his daughters about the cousin who broke the cycle instead of passing it on, and I kept the email because I want my kids to know what strength is for. If you ask me whether I regret anything, I’ll tell you I regret that it happened, I regret the twenty years we lost, and I do not regret the way I answered. I held them accountable, I protected the next person in line, and I forgave when forgiveness was the only door left between me and freedom. In the backyard on a Saturday the fort is made of couch cushions and the laughter is made of air I earned the right to breathe. The cycle is broken; the patterns are rewritten; the price of loyalty has been paid without passing the poison forward. Living well turned out to be not just the best revenge, but the only victory I wanted my children to inherit.

Years later, I built something I wish I’d had at twenty-three—a small nonprofit that teaches people how to verify, document, and say no without setting themselves on fire.

We called it The Quiet Ledger because most rescues don’t look like sirens; they look like spreadsheets, affidavits, and a voicemail saved twice.

Joanna ran a clinic night once a week, showing young nurses how to set boundaries with relatives who confuse sacrifice for entitlement.

Warren set up the databases and taught teenagers that money is a tool, not a mirror, and that love doesn’t require receipts.

Emma decorated the classroom corkboard with crayon suns and a banner that said, “We keep what we can prove, and we prove what we keep.”

On Tuesdays, I sat with people at metal tables and translated panic into steps: verify, document, escalate, rest.

No one clapped, but the room got warmer, which is the applause I trust now.

Sometimes a survivor would ask whether forgiveness was required to move forward, and I told them a truth that took me ten years to earn.

Forgiveness is a key you cut for your own door; it may open theirs, but that’s not your house to live in anymore.

Accountability, I said, is architecture; it makes rooms bear weight without collapsing on whoever is standing there.

Revenge feels like momentum until you realize you’re running on a treadmill someone else plugged in.

Justice is a budget you balance, not a bonfire you dance around; the light doesn’t last if you burn the furniture.

We kept the lights on with small donations and one quiet grant from a man who’d once been a boy standing in my office with shaking hands.

I filed every thank-you note the same way I filed every affidavit—alphabetized, dated, and believed.

Marlene sent a photo one spring of a backyard wedding under strings of lights, her husband in shirtsleeves, her hands steady on a cake knife.

I sent a card and a stand mixer because earned joy deserves equipment, not commentary, and she wrote back that the lemon curd finally set right.

We were not close, but we were no longer a case file; we were two adults who had learned to stop asking the past to pay our present bills.

When her first child was born, she mailed a picture with a note that said, “I’m doing the math differently this time,” and I believed her.

At Christmas, she addressed an envelope “To the uncle who taught me that proof can be kindness,” and I set it under the tree without explaining more.

Warren asked if people can become safe, and I said some do and some don’t, and our job is to build railings either way.

He nodded like a boy who already knew the answer and wanted to see if I would say it out loud.

One fall weekend, we drove to the old road where the farmhouse used to stand, now just a memory mapped by muscle and corn.

I planted a maple sapling at the edge of the public right-of-way, a legal kindness with roots, and told the kids it was for shade we would never sit under.

Emma asked what we were doing, and Joanna said we were making sure someone else’s summer would be kinder than ours had been.

I told them that legacies are not only the stories we repeat, but the heat that works, the porch that holds, the habit of telling the truth.

Warren pressed the soil with both palms the way you pat a stubborn blanket flat, and I thought about all the rooms I had kept upright since the collapse.

On the drive home, the sky turned the soft orange that makes even strip malls look temporary, and I felt exactly as temporary as I should.

Living well hadn’t erased anything; it had simply made room for everything else worth keeping, which is all victory ever needed to be.

A year after we planted the maple, a state senator asked me to testify about familial financial fraud, the kind that hides behind casseroles and prayer chains.

I told the committee the truth that doesn’t fit on bumper stickers—that love without verification is how predators get uniforms.

We drafted a bill that required independent confirmation for long-term support, third-party guardians for cognitively impaired relatives, and a paper trail worth more than anyone’s story.

Hospitals added a one-page consent that routed “helpful” relatives through an ombudsman, and banks built flags for “emergency wires” that repeated like weather.

The lobbyists called it overreach until a nurse read her father’s balance sheet into the record and the room remembered what grief sounds like in daylight.

When the vote passed, no one cheered, but three clerks wiped their eyes and I wrote Joanna a text that said, simply, We raised the floor.

Back at The Quiet Ledger, we printed the statute on bright paper and taped it over the coffee maker so no one would forget what a Tuesday can do.

Two months later, a kid who could have been me at twenty-three showed up with a folder and a tremor he tried to hide.

His aunt “needed help right now,” his mother was “sure,” and every sentence he brought me had a calendar stapled to it.

We walked through the steps—verify, document, say you’ll help after the doctor calls you back—and his hands steadied as verbs replaced panic.

He sent one wire for a legitimate copay, declined three for “consulting fees,” and learned that boundaries, kept early, don’t shatter later.

When it was over, he emailed a line I kept: “Thank you for teaching me that no is a form of love that survives the audit.”

I filed it next to a photo of Emma holding a cardboard sign that read, “Ask for proof, not apology.”

If you want to know what hope looks like where I live, it looks like a spreadsheet printed on a cheap laser, signed, dated, and believed by the person who needed it most.

Marlene came by on a Saturday with her husband and the baby who had her eyes and none of her history.

Joanna set out lemonade and a bowl of blueberries, and we talked about weather first, because most hard things need a soft on-ramp.

Marlene asked to see the maple we planted, and I told her it belonged to everybody, which is what good shade always does.

She apologized again—not like a ritual, but like an inventory—and I said the forgiveness had already happened and the trust would take the time it needed.

We didn’t touch the past beyond what the children could carry; we touched the herb garden instead and sent them home with basil like a blessing.

At the car, Marlene said, “Thank you for not making me the worst thing I did forever,” and I said, “Thank yourself for the next right thing, then do it again.”

When the door closed, Joanna leaned into my shoulder and whispered, “That was a good thing,” and I said, “So is this house with the heat on and the couch that’s ours.”

That night, Warren asked if Aunt Marlene was “safe,” and I told him safety is a project, not a label.

We talked about locks you fix and habits you fix and how both count as doors you get to walk through twice.

He wanted a rule, and I gave him a practice: believe change the way you believe a budget—after the numbers run, not before.

He smiled like a boy who already keeps receipts for feelings and filed the evening under “adults doing their best.”

Emma declared herself the basil police and wrote a rule on a sticky note: “No stealing plants from neighbors unless they say yes,” which is almost policy.

We laughed, and the room held the sound like it had waited its whole life to do that job.

Later, I checked the locks anyway, because some caution is stewardship and some is leftover weather; both let my children sleep.

I wrote a letter to the kid I was at twenty-three and sealed it in an envelope I hope my son never needs to open.

I told him to verify the first ask, because the first ask teaches every ask after it how to speak.

I told him love doesn’t require proof, but money always does, and that mixing the two without a ledger is how you drown quietly.

I told him the ramen years were not noble; they were unnecessary, and there is no valor in sleeping cold for a lie.

I told him the anger would keep him warm until it didn’t, and that forgiveness would feel like failure until it didn’t, and that both are just temperatures.

I told him to marry someone who can hold a room together with a sentence and then keep listening when she tells him to put the sword down.

I told him he will survive, not by being harder, but by being exact, and that exactness, kept kindly, is the door out.

The envelope went in the safe with birth certificates and the title to a car we paid off early because we finally could.

I labeled it “Only if needed,” which is how I feel about most of my old stories now.

Some nights I imagine the boy opening it and decide I’d rather he never has to; some nights I am the boy, and I read it to myself.

Joanna says the point of a past is not to disappear, but to be carried correctly, like a toolbox instead of a burden.

I keep the hammer and the level and the tape measure; I left the anvil by the highway.

When the house creaks, I listen and then I tighten what needs tightening, and I don’t hate the carpenter who came before me.

He tried with what he had, and now I try with more, which is the point of an inheritance that doesn’t ruin the next room.

On a Sunday that sounded like sprinklers and neighbor kids, I grilled chicken while Warren built a ramp for Emma’s scooter out of scrap wood that used to be a worry.

Joanna brought out potato salad and the kind of laughter that makes a place feel held, and the dog did crowd control like he was on salary.

Next door, a new couple asked about our maple, and I said it wasn’t ours, and they looked relieved without knowing why.

We ate on paper plates under a string of lights I swore I’d take down after last Christmas and never did because glow is a habit I’m keeping.

After dishes, I sat on the steps and watched the street do its evening shift—porch lights choosing on, a jogger waving, a delivery driver nodding like a priest.

In the living room, the kids turned the couch into a fort and then into a boat and then into a castle because nobody told them it couldn’t be all three.

I thought about what my father had wanted to matter to and decided this was better: a house with heat, a map with shade, and a ledger that closes every night at peace.

Later, when the lights were out and the dishwasher sang its small song, I looked at Joanna and said, “Thank you for teaching me when to stop.”

She smiled the way she did the first day we decided to live, not just survive, and said, “Thank you for learning.”

The maple outside lifted its dark hands against a sky I have no claim on and offered itself anyway, which is how gifts should work.

I don’t know what storms are coming; I know we built for them—policies and railings and a community that understands the word boundary.

If anyone asks me what the moral is, I tell them we don’t do morals here, we do maintenance: of houses, of laws, of hearts.

We keep the receipts that count and shred the ones that only keep us angry.

Then we wake up, turn on the heat we paid for, and try—in seven small ways before breakfast—to make sure no one else has to live cold for a lie.

By autumn, credit unions started calling to ask how to design accounts that loved generosity without enabling exploitation, and I told them to treat large recurring family transfers like scaffolding: inspect them on a schedule.

We wrote a two-signature rule for long-term care payments—one from the giver, one from a neutral verifier—and built a slow lane for emergencies that kept panic from breaking the speed limit.

The Quiet Ledger published a booklet with plain-English checklists and a sample phrase you can hand to a relative who thinks urgency outranks proof: “I will help after I confirm with your doctor.”

At night, I taught a six-week community course called Receipts and Mercy, and the only homework was to sleep with the heat on because you could.

Marlene mailed a photo from her nursing pinning ceremony, a white cap tilted over a face that finally looked like a future earned the hard way.

Joanna and I sat in the last row and clapped like strangers who had decided to be kind on purpose, then slipped out before the hugging started, because gratitude and boundaries can share a room without touching.

On the way home, we drove past the public right-of-way and the maple we planted had learned the trick of looking inevitable.

There was a winter where I realized my father had been dead long enough that I no longer expected the late-night call that required me to become architecture.

The quiet felt untrustworthy at first, like a street you walked after the plows finally came through, but the pavement held, and I learned not to invent storms out of habit.

Warren asked if he should write his college essay about resilience and I said try joy instead, because no one builds a house out of scars on purpose.

He wrote about the maple, Emma’s basil “policy,” and the day he taught a neighbor to say no without apology, and the admissions officer circled a line: “We kept what we could prove.”

Emma organized a “Proof Week” at her middle school—bring the source, cite your claim, change your mind in public if you learn something—and I sat in the back row grinning like a man who had lived long enough to see culture move.

City Hall passed an ordinance that folded our verification model into the clerk’s office, and the clerk hugged me in the lobby because bureaucracy can be tender when it remembers who it’s for.

That night I thanked Joanna for teaching me that warmth is a practice, not a miracle, and she said, “So is sleep,” and turned off the light.

On the twentieth anniversary of the first wire I shouldn’t have sent, a publisher offered me a memoir deal with a title about betrayal, and I said no because some stories should earn their quiet.

I gave a keynote instead to a room full of social workers, bankers, and pastors, and the talk was seven verbs long: verify, document, translate, escalate, rest, forgive, maintain.

Afterward a woman pressed my hands and said her church had adopted our “compassion with receipts” policy and the only thing they lost was confusion.

I went home to a porch light we never forget to turn on anymore and a couch fort that had become a spaceship and then a library, which is how furniture should live.

Joanna fell asleep with a book on her chest; I carried it to the nightstand and stood in the doorway long enough to believe my eyes.

Outside, the maple threw our shadow twice the height of the house, and I let it own the yard a while because some legacies grow better when you don’t tell them how.

I locked the door, checked the thermostat we paid for, and whispered the only benediction I trust now: the ledger balances, the heat holds, the house stands, and we keep the light on for whoever needs a better map.

Warren chose a college two states away with a dorm that smelled like detergent and possible, and we packed a minivan with bins that made his childhood look shockingly finite.

On move-in day, Joanna labeled cords like a quartermaster while I checked the window latch twice and taught his roommate how to file a maintenance request without apologizing.

At the parent session, I raised my hand and asked the dean whether the emergency fund had receipts, and three moms wrote down the question like a recipe worth keeping.

Before we left, I pressed an index card into Warren’s palm—the seven verbs in my handwriting—and he rolled his eyes like a person who would use them anyway.

He hugged Emma hard, promised to FaceTime on Sundays, and whispered to me, “I’ll build railings first,” which is the kind of sentence you let echo.

Driving home, Joanna said the quiet felt big, and I said big quiet is a room we earned, not a room we have to fill.

That night the maple shifted against the window like a good neighbor, and we slept with the heat set exactly where comfort turns into rest.

I wrote a will that didn’t read like a treasure map so much as a maintenance manual, and the first page said, “Leave the heat on for others.”

We set aside money for The Quiet Ledger, for saplings on public right-of-ways, and for the kind of no-questions fund that answers with documentation and a warm blanket.

I wrote letters to both kids explaining that money is a tool, love is a practice, and legacy is the shape of rooms that keep strangers safe.

I told them if anyone asks for help loudly, listen softly, and if anyone asks for proof gently, provide it without turning it into a performance.

I named Joanna executor because she can keep a kitchen and a boardroom upright with the same sentence, and that’s the only qualification I trust.

At the end, I added a line I wish my father had left me: “If you must choose between being right and being kind, be exact and then be kind.”

We signed the papers at a cheap oak desk that had seen better water rings, and it felt like tightening a hinge before a storm we might never meet.

Years turned like sensible pages, and Marlene drove up one Sunday with a teenager who wore honesty like a jacket that fits.

They brought lasagna and a story about a patient who died held, not alone, and we ate on the deck while shade did what shade is for.

She asked if the house ever felt too quiet, and I said quiet is not emptiness, it is room for the good noise to pick its time.

We walked to the maple and she ran her fingers along the bark the way people read names on old monuments, then she planted basil starts in Emma’s square and didn’t take any home.

On the way back, we passed a flyer for a neighborhood meeting about “compassion with receipts,” and I didn’t have to explain whose idea that had been.

That night Joanna and I took the long loop around the block because our knees like even sidewalks, and we talked about nothing urgent until it became everything important.

In bed, with the thermostat humming and the house breathing evenly, I thought about the ledger, the heat, and the light, and realized we had built a place where all three hold without me watching.

The first real storm in years came sideways, a wall of rain that made the gutters speak and the street forget its lines.

The power flickered once, considered its options, and stayed, because the panel labels were honest and the maintenance wasn’t theater.

I stood at the window and watched the maple bend with grace instead of panic, the exact angle a good life learns after enough wind.

Across the street, a neighbor’s porch light went dark, and two doors opened—ours and theirs—and the extension cord crossed like a handshake.

Emma brought blankets without asking and Warren set the kettle on, and no one announced that this is what family does.

When the power came back, we untangled the cord and waved like people who had practiced for a moment they hoped would never arrive.

I slept hard that night, not because nothing broke, but because what held held for the reasons we built it to.

Warren graduated under a sky that threatened rain and kept its word only after the speeches, which felt like manners.

He hugged us in a gown that smelled like gym dust and ambition, and he whispered he’d found a job with a clinic that calls “no with proof” a vital sign.

Emma started a neighborhood zine called Receipts & Sunlight and interviewed elders about the best “yes” they ever had to earn.

Joanna framed a picture of the four of us at the ceremony, the maple a green smudge in the background like a signature we learned to write together.

That night we ate takeout on the floor because the table was full of frames and envelopes and the dog had claimed the rug with missionary zeal.

I told them I was proud in the clumsy way men like me do—too many facts, not enough adjectives—and they forgave me with laughter.

Later, I turned off the porch light and turned it back on, the smallest vow I know how to keep.

I stepped back from The Quiet Ledger on a Wednesday that felt like Tuesday in the best way, and the new director brought fresh markers and the same verbs.

We took a picture in the empty classroom with the banner Emma made, and I slid my key across the table like a tool, not a trophy.

The board baked a cake in the shape of a file folder and we ate it with plastic forks because sincerity doesn’t need china.

Afterward, I walked past the community bulletin board and saw a flyer I didn’t write for a workshop I used to teach, and nothing in me flinched.

At home, I put the key on a nail in the garage with the spare extension cord and the jumper cables, right where future-me would reach without thinking.

Joanna met me on the porch with two mugs and one look that said the calendar had been waiting for this empty square.

We sat shoulder to shoulder while the house breathed even and the maple drew slow circles on the lawn, and I understood that letting go, done right, is just another form of keeping.

Clayton called to say Paula had slipped away on a Wednesday that felt orderly, and Joshua asked if I would speak at a small gathering under a cottonwood behind the facility. I said a few plain sentences about care that arrives with proof and leaves with dignity, and people nodded because grief prefers declarative grammar.

Afterward Joshua introduced me to his twins, who wore matching sneakers and the look kids have when grownups tell stories without monsters.

Clayton squeezed my shoulder and said, “You kept the worst from repeating,” and I told him the truth—I had only slowed it down and taught others where the brakes were. On the drive home, Joanna said it was good work even if no one clapped, and I said good work doesn’t need applause, just continuity.

That night I wrote a one-page test for anyone who would ever ask my kids for money: Who’s the doctor, what’s the plan, where’s the consent, when did we verify, why is this urgent, how do we audit the follow-up. I taped it inside the hall closet where we keep the flashlights, because the best tools are the ones you can find in the dark.

A new couple moved in next door with a baby who hiccuped like a metronome, and they asked about our maple as if it were a neighborhood elder.

We told them what we tell everyone now—that good shade belongs to anyone who needs to stand under it, and the only rent is respect.

A week later their furnace died on the coldest night of the year, so I ran an extension cord and Joanna knocked with a thermos and no speeches.

They tried to apologize for the inconvenience and I said inconvenience is what you call generosity before it becomes a habit.

By morning the repair truck was in their driveway and the cord was coiled back on its nail, and I felt the house exhale like it approved.

Emma put a flyer on the block email list titled “Compassion With Receipts—Home Edition,” and the bullet points read like a checklist we’d been writing for years.

By spring, three more porches had spare cords on labeled hooks, and our street had quietly learned a word I spent half my life chasing—enough.

When I finally retired, the team gave me a plaque shaped like a spreadsheet, and I laughed because they knew the language I spoke when feelings got complicated.

Joanna booked us a long drive with no itinerary and a glove compartment full of state park maps, the kind that fold wrong and still get you there.

We sent the kids a group text with the alarm codes and a note that said, “The thermostat is set where comfort becomes stewardship—keep it that way.”

On a blue afternoon in a town with one stoplight, we found a nursery that sold saplings wrapped in burlap, and we bought two without deciding where they’d go.

That night we stayed in a motel that smelled like lemon cleaner and promised nothing, and we slept hard because the promise was kept anyway. In the morning I wrote a postcard to The Quiet Ledger’s new director: “The work was never mine, it was Tuesday’s; keep Tuesday honest.” We turned the car toward home, and when the roofline appeared and the porch light blinked on, I understood that the quiet I’d been chasing wasn’t silence at all—it was a house where the heat holds, the maple leans, and the doors we built stay open just long enough for the next person to walk through.

We planted the first burlap-wrapped sapling on the public trail behind the elementary school, just off the footpath where parents wait with coffee and patience.

The second went into the median by the library, a place that already knew how to hold quiet and wanted shade for the line that forms before story hour.

Warren called the city, filed the right forms, and taught me the romance of permits—how rules, obeyed on purpose, can be love in municipal clothing.

Emma painted a small wooden sign that said, “Public Shade—Please Water When It’s Hot,” and three days later someone else added, “We Did.”

Joanna convinced the PTA to stock a bin of five-dollar gift cards next to the lost-and-found, labeled “Compassion With Receipts,” and the bin never stayed empty for long. A bench arrived one Saturday with a plaque that didn’t mention us, only a sentence: “For anyone who ever had to wait in the sun alone.” I sat there longer than I meant to, watched people choose the shade without thinking, and felt the odd mercy of not being the story anymore.

Warren’s clinic put our seven verbs on the intake clipboard and called it bedside policy; outcomes improved, tempers didn’t, and that was the right order.

Emma’s zine grew into a community newsletter with footnotes, corrections, and a monthly feature where elders changed their minds in print with grace.

Joanna started a scholarship for home-health aides who keep families honest with kindness, and every recipient sent a postcard that smelled like effort.

The Quiet Ledger hired someone younger, sharper, funnier, and the first thing she did was cut three pages from our handbook and add a nap policy.

A letter came from a man I’d never met who said, “Your checklist made me keep the heat on, and the heat made me sleep, and the sleep made me kind,” and I filed it under Enough. I wrote one last list for myself—wake grateful, verify gently, hug on purpose, water the trees, call your kids, forgive without applause, sleep with the thermostat set to merciful. Then I stopped writing lists for a week and nothing broke, which felt like the graduation I didn’t know I’d been studying for.

If anyone ever writes my obituary, I hope they keep it short—he left the light on, he labeled the breaker panel, he said no with proof and yes with warmth.

Tell them I learned too late that ramen is not a sacrament and that anger is a coat you can hang up when the weather changes.

Tell them the first maple taught me patience and the second taught me humility, and neither asked me who I had been before I showed up with water.

Tell them my father taught me hard work and the cost of not doing it on yourself, and my mother taught me apology and the cost of waiting too long to say it.

Tell them my wife built a house by speaking in complete sentences, my son built railings before bridges, and my daughter turned sunlight into policy.

If there must be a moral, let it be maintenance: of heat, of ledgers, of promises that keep a stranger warm when you have already gone to bed.

As for me, I will sleep now, with the porch light on and the thermostat steady, grateful that the balance held and that the doors we built stayed open just long enough for the next person to walk through. On a Tuesday, because it was always a Tuesday, the mailbox held three things that felt like a chord—an alumni magazine, a water bill, and a note from a woman whose mother finally slept warm.

I paid the bill first because keeping the heat on is how faith behaves when it grows up, then opened the note and let it say what numbers can’t without help.

She wrote that our checklist had made Christmas gentle, that proof had quieted an uncle who specialized in emergencies, and that the thermostat felt like a prayer answered responsibly. The alumni magazine ran a feature about “impact,” and my name wasn’t in it, which struck me as accurate and comforting. Impact is a dent; care is a contour, and I had learned to prefer one shape to the other when the wind picked up. I put the note on the fridge between Emma’s basil policy and Warren’s seven verbs, and the kitchen felt like a map anyone could read. Then I took a walk to the library median, touched the second maple, and said out loud to no one that Tuesday had kept its promise again.

The library built a small exhibit on neighborhood kindness that didn’t look like much—two benches, a looping slideshow, and a pegboard of printed checklists with take-one clips. Kids drew their houses with labeled breaker panels, grandmothers shared soup recipes with margins that said “check the pilot light,” and someone framed our “compassion with receipts” flyer like a hymn.

Marlene stopped by in scrubs between visits, left a photo of a hand she was holding at 3 a.m., and wrote “held” on the label instead of the patient’s name.

Joanna pointed to a corner where a teenager had taped up a college essay prompt and a receipt from a thrift-store suit, and we both nodded at the economy of hope.

I added a single laminated card—“Verify, Document, Translate, Escalate, Rest, Forgive, Maintain”—and the librarian slid it higher where small hands wouldn’t tear it. A man I didn’t know stood a long time in front of the slideshow, then borrowed a pen from the desk and wrote “thank you” on the sign-in sheet like a signature.

We left without a speech, bought lemonade from the kids’ table out front, and decided to overpay because their ledger didn’t need to learn scarcity today.

Years later, when the doctor spoke gently about clocks and comfort, I asked Joanna to read the letters in the safe and keep only the map.

We made a list not because we had to, but because lists had turned our lives from weather into seasons—call the kids, water the trees, tell Tuesday it did fine.

Warren brought the grandkids to jump on the couch cushions and call it a spaceship, and Emma checked the thermostat and declared it “merciful,” which made me prouder than any plaque. At dusk, the maple laid our shadows across the lawn like a blanket that knew our measurements by heart.

I walked the circuit one last time—breaker panel, porch light, spare cord on its nail—and touched each thing the way you thank a tool for outlasting the job.

Joanna took my hand and said, “Everything that needed doing got done,” and I believed her the way you believe a well-balanced ledger.

When the house settled and the night chose quiet, we left the porch light on, not as a metaphor, but as maintenance for whoever might still be finding their way.

The week after the doctor’s talk, I made a binder labeled HOUSE, PEOPLE, TUESDAY, because instructions are the kindness you leave behind.

Inside I drew a map of the breaker panel, taped the seven verbs to the first page, and wrote “Leave the heat on for others” in my best block letters. I added the passwords in pencil, the safe combination in metaphor, and a note to Warren that said he could change both as long as he left the porch light alone.

I told Emma the basil policy could outlive me if she kept rewriting it every spring, and she promised like a legislator who understands seasons. Joanna checked my checklists for holes and found none I wasn’t already plugging with tape and intention. We set the binder on the closet shelf beside the flashlights and the spare cord on its nail so the future would know where the past kept its tools. Then we took the long drive to the library and back, because good handoffs happen before the meeting, not after the emergency. On a Tuesday, because it was always a Tuesday, I slept past the thermostat’s first click and didn’t wake again, which is a kind of punctuality I’d been practicing for years.

Joanna called the kids, opened the binder, and let the house tell them what needed doing without making grief do the work. Warren checked the panel and the light, Emma watered the basil and the maples, and the dog laid down like he had memorized this duty too. The Quiet Ledger sent a card with a receipt for a scholarship in my name, and Joanna smiled because even our memorials filed clean. The service was small and practical, more like a maintenance window than a spectacle, and the eulogy fit on one page with verbs instead of adjectives. Afterward they set the thermostat to merciful, left the porch light on, and wrote “Tuesday kept its promise” on the family calendar in ink. The house held, the heat held, and the maples lifted a shade that belonged to anyone who needed to stand there a while.

In spring they planted a third maple by the bus stop where tired people learn how long a minute is. The plaque didn’t have my name; it said only, “Proof and kindness,” which sounded like a marriage worth keeping. Warren brought a level, Emma a watering can, Joanna a bag of mulch that smelled like patient work. Neighbors stopped, smiled, and pressed the soil flat with their palms as if swearing a quiet oath together. A kid leaned against the trunk and kept reading, which is the only dedication I ever wanted. That night the wind came soft and the new leaves trembled like a receipt still warm from the printer. Joanna slept with the window cracked, and the house breathed evenly, unafraid to remember how the story had learned to end.

Years later, Warren wrote the third edition of the clinic’s “No With Proof” protocol, and the footnotes thanked his mother for still labeling cords.

Emma turned Receipts & Sunlight into a civics unit for eighth graders, and the principal sent Joanna a note that said, “Your daughter made our school honest.”

The city folded “compassion with receipts” into its grant guidelines, and people started saying, “That sounds like maintenance,” when they meant love.

The Quiet Ledger celebrated ten years without me by making the nap policy mandatory and mailing stickers that read, “Rest is part of verification.” On the anniversary, they sent Joanna a one-page report with heat maps instead of headlines, and she framed it because quiet is her favorite graph. The family still met on Tuesdays to water trees, check lights, and read one line from the binder aloud so the house would remember its job. At dusk, the porch light chose on by itself, which was a lie the fixture told kindly to make everyone feel the continuity we had built into the walls.

The house lived by the rhythms he had written onto card stock: the labeled breaker panel, the spare cord hanging on its familiar nail, the thermostat stopped at “merciful,” and the porch light choosing “on” like a small promise. Joanna kept the “HOUSE, PEOPLE, TUESDAY” binder the way a lighthouse keeps its lens, patiently polishing, resetting to center, leaving it ready for the hours when fog keeps pretending to be weather.

Warren replaced bulbs before they burned out, because there are promises you are only allowed to keep, not gamble with. Emma kept updating the “basil policy,” adding a line he would have nodded at with a grin: “Kindness is payable upon receipt, interest charged in sunlight.” Thank-you letters from strangers still arrived, neat as invoices stamped “PAID,” saying a list of seven verbs had kept a winter night warm or pulled an “emergency” phone call without proof out of someone’s throat. On the kitchen shelf, the small slip of paper with the italic line—“Leave the heat on for the next person”—had yellowed with years, but the ink refused to fade. In that amber light, everything he built kept going, not by miracle, only by good habits performed on time.

The street learned the language of “enough”: cords on the right hooks, color-coded panels, a water heater tagged with its service date, and a text chain that asked “proof?” in a gentle voice. When the house next door lost heat on the coldest night, two doors opened at once—ours and theirs—and a cord arced between them like a handshake that didn’t need words.

An elderly neighbor brought over a pot of soup and a receipt for the new propane tank; a kid returned a pack of batteries with a sticky note that read, “all set—thanks for the labels.” In front of the library, the second maple laid shade over the line for story hour; on Emma’s little wooden sign “Please water when it’s hot,” someone had scribbled, “We did.” In the corner of the schoolyard, the bench with its small inscription—“For anyone who ever had to wait in the sun alone”—was never empty, and the quiet there was never empty either. Block meetings stopped being speeches and became a “neighborhood accord” taped to butcher paper with exactly three items: plug in, label, verify. The entire block switched on in a slow wave, like a runway for decent landings, and no one posted a photo except to pin it on the library board.

Inside that house, the newer generations chose their parts in the small music he left behind: Warren rebuilt the “No With Proof” protocol at the clinic, Emma turned “Receipts & Sunlight” into a hands-on civics unit for eighth graders. They knew without prompting to open the binder to the first page, where seven verbs stood in a straight line like lane markers: verify, document, translate, escalate, rest, forgive, maintain. The thick binder began to look like a thin prayer book, not to be worshiped but to be used—like a wrench, a marker, a cord.

And “forgiveness,” when it arrived on time, was no longer a ritual for the offender, but a permit for the living to travel light. Anniversaries didn’t need names; the house just ate soup, checked locks, turned the porch light on, and wrote “Tuesday kept its promise” on the calendar in durable ink. In every corner, there was evidence of a love that had grown up: pencil marks on the doorframe measuring the kids, the wear on the step from the same pair of shoes going out to water. And in the middle of the room, laughter lay easy across the cushions like an asset no one wanted to pawn again.

The city learned a few simple, difficult things: emergency aid required a second set of eyes, powers of attorney got reviewed by a judge, and hospitals issued a consent form exactly one page long and readable in one breath. Pastors, social workers, and bankers wound up in the same room and agreed that “receipts with heart” didn’t shrink compassion; it just kept it from leaking.

The librarian nudged the laminated “Seven Verbs” card higher on the shelf, just out of reach of small hands—but not so high grownups had to stretch. The bulletin board added more sheets—“Shade Tree Permit,” “Front-Porch Cord Guide,” and a tiny corner that read, “Nap Policy: Rest is part of verification.” Even the local newsroom hung a strip above the coffee maker: “We thought we needed heroes; turns out we needed checklists.” In the comments of one piece, a man typed exactly two words, “thank you,” as if signing a normal, durable pledge. In that picture, he was no longer the center, which is exactly why the story stood.

A storm came the old way—rain slanting, tree shadows tilting just enough—and everything kept the function it had rehearsed. The porch light didn’t speak in metaphor; it did its job—called the lost, kept the key dry, threw a warm stripe across the house number that had long since stopped being a code. The kettle’s whistle in the kitchen sounded like a prayer that pays the electric bill; the smell of tea was a lingua franca every porch could speak.

When the neighbor’s power died, the spare cord already hung on its nail, stepped across the painted line like a handshake that walks straight. The night’s only commentary was a note taped to the door: “Plugged in—No. 12,” under which a child’s careful signature trembled with pride. In the morning they unplugged, coiled, rehung, and everyone felt they had crossed something that was not luck. In the kitchen the binder shut as if to say “roll call complete,” then translated itself into silence so people could eat breakfast.

In the end, the story didn’t hunt for an ending; it looked for a way to keep working longer than the people who started the machine. Some days Joanna sat on the step, fingertips on the edge of the “Public Shade” plaque, thinking about a whole life distilled to a handful of good habits and one sentence written neatly. Some days Warren stood before a room pointing to a heat map he called “the quiet graph,” explaining why “merciful” is the default setting a house can be proud of.

Some days Emma pasted another line onto the basil policy—“Water a neighbor’s garden when they’re away”—and got a bag of lemons and a “watered” note in return, the kindest proof there is. And some nights the street lit up in a slow, breathing wave, the maple shook like a yes, and the door locks slid home as gently as a well-balanced ledger. If anyone asked “what’s the lesson,” they heard the same answer as always: there isn’t a moral, there is maintenance—of heat, of books, of the promise kept for the next person. In that deliberate ordinary, victory wasn’t revenge and wasn’t only justice; it was living better, day by day, and leaving the porch light on for anyone still finding their way home.

News

🧾Grab a mop,” the officer sneered when she spilled her coffee. By noon, he was standing in front of her bench — shaking.

A prejudiced cop mocked a middle-aged Black woman by spilling coffee on her. Moments later, he learned who she really…

🚨He mocked her in a coffee shop. Two hours later, he realized she held his career in her hands.

A prejudiced cop mocked a middle-aged Black woman by spilling coffee on her. Moments later, he learned who she really…

⚖️police officer laughed when she spilled coffee. He had no idea she was the judge he’d stand before by noon.

A prejudiced cop mocked a middle-aged Black woman by spilling coffee on her. Moments later, he learned who she really…

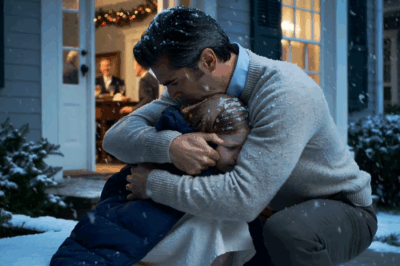

🧨My wife left my daughter outside on Christmas Eve.

That first night in the hospital felt like a borrowed hallway, too bright and too quiet for honest sleep. A…

🧊They left my daughter out in the cold. I walked in, hit record, and watched their faces fall.

That first night in the hospital felt like a borrowed hallway, too bright and too quiet for honest sleep. A…

❄️On Christmas Eve, I found my daughter freezing on the porch. Inside, my wife was laughing by the fire. That was the night everything broke.

That first night in the hospital felt like a borrowed hallway, too bright and too quiet for honest sleep. A…

End of content

No more pages to load