At 8,000 feet over Dover harbor, a group of Fw 190s owned the sky. The English coast spread below them, defenseless. Then a British fighter appeared, closing fast. It had a massive four-bladed propeller, thick wings, and bold yellow stripes across its fuselage. The aircraft looked brutish, almost primitive compared to their sleek Focke-Wulfs.

They dove to escape, but somehow the striped fighter stayed glued to their tails. Its engine screamed at full throttle, a sound unlike any aircraft powerplant they’d heard. Then came the 20-millimeter cannon fire. Weighed down by their bomb loads, the Fw 190s couldn’t shake their pursuer.

In desperation, they jettisoned everything, their ordnance splashing harmlessly into the channel below, while they headed back to safety. At 440 miles per hour, the striped fighter made clear the Luftwaffe’s dominance was over. The Challenge England’s southern coast lay exposed in 1940, with defenders scanning gray skies for the next wave of Luftwaffe bombers.

The Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane, while heroes of the Battle of Britain, faced an increasingly formidable opponent. The Messerschmitt Bf 109E, with its superior rate of climb and speed at altitude, began to systematically outclass Britain’s fighters. Air superiority, a cornerstone of defense, hung by a thread.

RAF commanders understood this new threat. Intelligence warned that the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, an advanced German fighter, would soon make existing aircraft obsolete. In response, the Air Ministry issued Specification F.18/37, calling for a fighter that could operate at speeds approaching 450 miles per hour at 15,000 feet, armed with a powerful battery of cannons.

Sydney Camm, the brilliant designer behind the Hurricane, faced an audacious challenge. His response was to install the massive Napier Sabre engine into an entirely new airframe. The Sabre’s 24 cylinders were arranged in an H-configuration, displacing 2,238 cubic inches and generating over 2,200 horsepower—more than double the power of the Merlin engine in a Spitfire.

Fully loaded, the new aircraft would weigh around 11,000 pounds, with a 41-foot wingspan and a 14-foot propeller—the largest ever on a single-engine fighter. Initial designs for armament included 12 .303-inch Browning machine guns, but it was quickly decided that the future lay with heavier firepower.

On paper, the new aircraft, the Hawker Typhoon, promised to be a dominant force, capable of speeds of 400 miles per hour at 18,000 feet. The Air Ministry, convinced by the projected performance, ordered 1,000 aircraft before the prototype had even left the ground. First Flight Terror The morning of February 24, 1940, at Hawker’s Langley airfield was cold and gray.

Philip Lucas, chief test pilot, squeezed into the cramped cockpit of Typhoon prototype P5212. He’d flown dangerous machines before, but nothing as experimental as this. The Napier Sabre engine, 24 cylinders primed with exacting fuel and ignition timing, was a beast waiting to wake.

Two Coffman starter cartridges sat ready, explosive jolts to drag the engine into life. The first cartridge fired. The Sabre coughed, shuddered, then erupted in a roar that rattled hangars and sent ground crews diving for cover. Blue-white flames spat six feet from the stub stacks. Taxi tests were unnerving. Controls were heavy, sluggish.

Even at 40 miles per hour, the rudder demanded every ounce of Lucas’s strength. Torque from the massive propeller yanked the Typhoon sideways with each throttle input. Takeoff magnified every danger. Lucas shoved the throttle forward. The Typhoon surged down the runway, hitting 100 miles per hour in eight seconds, nose swinging wildly under torque.

Sweat beaded as he wrestled the rudder, easing the stick only at 120 miles per hour. The climb was furious, 2,740 feet per minute, but the plane trembled under its own power. Then, at 15,000 feet, a violent flutter ran through the controls. Pressure shifted at the rear fuselage where the main section joined the empennage. The metal twisted, a jagged line splitting open, daylight glaring through the gap.

Lucas’s mind raced: Bail out and risk the Sabre exploding. Or wrestle the Typhoon down. He chose the latter, gripping the controls, praying the fuselage held. The descent was a battle. The landing gear shuddered on contact, the airframe groaning, but Lucas coaxed the aircraft to a stop. The Typhoon survived, but its troubles had only just begun.

Hawker’s design team raced through the summer of 1940 to fix the flaws exposed by Lucas’s test flights. The Typhoon’s tail section was redesigned with external fishplates, and internal bulkheads were reinforced. Wing spars were strengthened to handle the massive engine’s torque.

The original 12-gun layout was scrapped in favor of four 20-millimeter Hispano cannons, giving the fighter a sharp increase in firepower. September brought the second prototype, P5216, but new problems surfaced. The Napier Sabre’s sleeve valve timing remained erratic, cylinder temperatures swung wildly, and power surged unpredictably, causing frequent engine failures.

Starting the engine had become an elaborate ritual of fuel priming, ignition timing, and sheer hope. Mechanical gremlins haunted every flight. Fuel vapor ignited on hot exhausts, forcing pilots to scramble free while crews doused the nose with foam. Engines often had to be replaced entirely.

Even more insidious was carbon monoxide leaking into cockpits, forcing pilots to wear oxygen masks even below 10,000 feet. In training, a Typhoon suddenly twisted into a spin, its pilot overcome by fumes before he could react. It plunged toward the ground. Another hazard was the car-door canopy, hinged like an automobile door. It made ground servicing easier but in combat turned into a cage.

At speed, wind pressure jammed it shut, trapping pilots inside damaged aircraft, even when fire spread through the cockpit. As one pilot put it, describing the stopgap protections: [QUOTE] “They got fire extinguishers like they are going out of fashion.” By December 1940, the Typhoon program teetered on the brink. Every flight revealed new mechanical or structural failures, and squadrons reported more losses from faults than enemy action. The fighter meant to dominate European skies had become a liability.

But salvation would come from an unexpected source. June 1941 brought alarming intelligence from RAF photo reconnaissance over northern France. German airfields revealed short-winged, radial-engined fighters unlike anything seen before. By August, the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 began appearing over the English Channel.

Designed by Kurt Tank, the Fw 190 was a compact machine. Its BMW 801 radial engine produced 1,677 horsepower in an 8,770-pound frame. With wing loading around 42.3 pounds per square foot, it had exceptional maneuverability, while top speeds exceeded 400 miles per hour at 20,600 feet—faster than the Spitfire Mark V at operational altitudes.

Armament was equally formidable: two 13-millimeter machine guns and two to four 20-millimeter MG 151/20 cannons allowed German pilots to engage from long range with devastating effect. RAF Fighter Command faced a crisis. Spitfire Mark Vs were outclassed below 25,000 feet. The Fw 190’s blistering roll rate gave Luftwaffe pilots clear advantages, allowing German formations to strike coastal targets before interceptors could respond.

Squadron Leader Douglas Bader, the legless ace, encountered Fw 190s over northern France in August 1941. After an engagement where his squadron lost three Spitfires without downing a single German fighter, he reported facing aircraft that: [QUOTE] “climbed like rockets [and] rolled faster than anything we’ve seen,” The Typhoon program suddenly became urgent.

But despite its mechanical flaws, it offered one critical edge: speed. Below 15,000 feet—the Fw 190’s favored altitude—the Typhoon could reach over 400 miles per hour in level flight, with dive speeds exceeding 520 miles per hour, allowing pilots to chase fleeing Germans across the Channel. Flight Lieutenant Ian Mallet recalled the acceleration when hot pursuit was set in motion: [QUOTE] “It was like being hit in the back with a sledge hammer when you opened the throttle.

” The Typhoon, once on the verge of abandonment, would find its purpose. By December 1941, No. 56 Squadron was operational at RAF Duxford. The Typhoon still had reliability headaches, but key improvements had enhanced safety and performance. Car-door canopies were swapped for sliding bubbles, giving pilots better visibility—and a real chance at escape if things went wrong.

Tail sections received external fishplates, and oxygen masks became standard to fight carbon monoxide leaks. On January 20, 1942, Typhoon pilots flew the aircraft’s first operational interception. A Mark IB, decorated in bold yellow recognition stripes, closed in on German fighters over Dover harbor at 8,000 feet.

The Napier Sabre screamed at full throttle, pushing the fighter to 440 miles per hour—unheard-of speed at that altitude. German pilots, pushed to their limits, broke formation and dove for the French coast. The Typhoon stayed glued to them, 20-millimeter cannon fire tearing through wings and fuselage. The Germans weren’t ready. Shocked by the Typhoon’s speed, they jettisoned their bombs and fled back east.

Within weeks, these low-level interceptions became routine, sealing the Luftwaffe’s daylight fate over the Channel. By March 1942, German daylight raids had effectively ended. With its role locked in, the Typhoon was reshaped into the RAF’s most feared ground-attack weapon. But the aircraft’s transformation was far from complete.

The Typhoon had proven its worth against Fw 190 formations, but by late 1942, RAF planners envisioned a more aggressive role. Any invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe would demand aircraft capable of destroying armor, fortifications, and supply lines. The Typhoon’s immense Napier Sabre engine provided power unmatched by other fighters.

While a Spitfire Mark IX struggled with a single 500-pound bomb, the Typhoon was capable of lifting two 1,000-pound bombs with minimal effect on its handling. No. 181 Squadron, formed at RAF Duxford in September 1942, was the first to fly bomb-equipped Typhoons operationally. Press correspondents quickly dubbed them “Bomphoons,” a nickname that stuck despite official scowls.

Squadron Leader Derek Walker-Smith led the first missions in October to strike German supply dumps and coastal batteries near Cherbourg. His formation cut through thick coastal haze, a fragile cloak against the dangers below. Waiting in the gray sky, German 88-millimeter flak guns, radar-directed and potent, shredded the air.

Walker-Smith’s flight often plunged straight into a ‘flak wall,’ exploding fragments whistling past, hammering wings and fuselage. Each Typhoon carried its two 1,000-pound bombs with delayed fuses, forcing pilots to hold level, straight flight for 15 tense seconds under concentrated fire. Every nerve screamed to maneuver or peel away, but discipline held them steady.

Then, the bombs dropped, detonating in towering fireballs that shattered supply dumps below. Yet the cost was stark: two Typhoons never returned, and three more limped back with heavy flak damage. Aircraft would return riddled with holes, trailing fuel vapor, and often requiring major repairs.

The limitations of bombing heavily defended targets were becoming clear, but a revolutionary solution was already in development. The solution came from the RP-3 rocket. This 60-pound projectile, with a high-explosive or armor-piercing warhead, could penetrate up to four inches of armor. Unlike bombs, rockets allowed for attacks from varying altitudes and angles, letting pilots maneuver defensively while striking with immense firepower.

Installation was tricky. Each Typhoon carried eight rockets on rail launchers, four under each wing. The rails added 400 pounds and created significant drag. The rockets’ forward center of gravity altered the aircraft’s trim, forcing pilots into extensive retraining. Additional armor was added to protect the pilot and critical systems.

Combined with its four 20-millimeter Hispano autocannons, the Typhoon’s firepower was so destructive that it earned comparisons to a naval destroyer. A two-second burst could deliver 86 cannon shells. In October 1943, No. 181 Squadron launched the first operational rocket strikes with RP-3s against German coastal radar stations near Calais.

Each rocket carried a 25-pound warhead, aimed at the concrete bunkers and flak positions of the Atlantic Wall. Pilots dove at shallow angles, rockets streaking past wingtips in pairs. The warheads ripped through fortifications that had shrugged off conventional bombs. Concrete splintered, steel twisted, and radar antennas toppled in clouds of smoke and dust.

The strikes were precise, ruthless, and spectacular—a new weapon that turned previously impregnable positions into shattered wrecks. By December, 18 rocket-equipped squadrons formed the core of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force. Intensive training covered target identification, ammunition selection, and coordination with forward ground controllers.

By spring 1944, the Typhoon had transformed from a troubled interceptor into a fearsome fighter-bomber. The morning of June 6, 1944, began with an eerie stillness, over the fields of southern England. In briefing huts lit by dim lamps, young pilots leaned forward, listening as fingers traced lines across a giant map of Normandy.

The German defenses were marked in thick red, a wall of artillery and armor waiting on the far shore. Outside, crews worked furiously in the gray dawn. Paint still tacky on their hands, they had slapped on the new invasion stripes overnight—black and white bands circling fuselage and wings. It was a desperate safeguard to prevent Allied gunners from mistaking friend for foe in skies about to fill with hundreds of aircraft.

The Hawker Typhoons squatted on the grass, brutish machines built not for grace but for power, their four-bladed props gleaming in the first light. Ground crews pulled the chocks. Compressed air hissed. Then the Sabre engines came alive with a guttural snarl that shook the huts and rattled windows. One by one, the Typhoons surged forward.

They climbed into a bruised sky, clouds hanging low and heavy. Beneath them stretched the English Channel, gray and restless, yet transformed by the invasion armada. From horizon to horizon, ships covered the water: destroyers, transports, landing craft, and battleships. The Typhoons leveled off at speed, 380 miles per hour, each carrying eight rocket projectiles and the brutal punch of four 20-millimeter cannons. The crossing lasted 20 minutes.

Then the coastline broke through the clouds. Normandy spread below, already torn by naval bombardment. Pillars of smoke twisted into the sky. Roads behind the beaches were crawling with German reinforcements, Panzer IVs, half-tracks, supply trucks, funneling forward through hedgerows.

The RAF’s revolutionary close support system kicked into motion. Forward observers lit the fields with white phosphorus markers, each burst painting a target in the bocage. Typhoons rolled into dives, the horizon flipping as the Sabre engine’s howl deepened into a growl. At 800 yards, pilots let loose their rockets. They ripped away in streaks of fire, slamming into lead Panzers and other German positions.

More followed in quick succession, squadrons peeling into steep attacks, cannons hammering. Half-tracks disintegrated, anti-tank crews broke and scattered as 20-millimeter shells walked across their positions. In the hedgerows, vehicles burned. By afternoon, the 21st Panzer Division’s assault timetable lay in ruins.

German commanders grimly reported that daylight movement near the beaches had become impossible. Above the invasion fleet, the Typhoons circled back through the clouds, their wings empty. The RAF’s close air support in Normandy broke with every tradition. Forward air controllers advanced alongside the infantry, VHF radios clutched securely.

With a smoke marker and a quick call, Typhoon strikes could hammer enemy positions within minutes, bypassing the slow, bureaucratic chains of command that had plagued earlier battles. This immediacy became the key that unlocked the German defenses. Through June and July 1944, Typhoon squadrons became the spearhead of Allied tactical air power.

They tore through German armor, columns of troops, and headquarters with mounting accuracy. One raid near La Caine left an unforgettable mark: Typhoons struck a German headquarters, wounding General Geyr von Schweppenburg, commander of Panzergruppe West, and eliminating most of his staff. German armored coordination stalled for two full days, granting the Allies crucial breathing room to press forward. The strike’s efficiency sent a chilling message across the battlefield.

The tempo was relentless. Four or five sorties per pilot per day became routine, a punishing cycle of climb, attack, and return. On the ground, Typhoon turnarounds were a spectacle of organized chaos. Ground crews, smeared with oil and sweat, replaced rocket loads in under 10 minutes, often while pilots remained strapped in.

The Typhoon struck with a force that seared itself into memory. Horst Weber, an SS panzergrenadier, remembered: [QUOTE] “We had four Tiger tanks and three Panther tanks … We were convinced that we would gain another victory here, that we would smash the enemy forces.

But then Typhoons dropped these rockets on our tanks and shot all seven to bits. And we cried…” Stuart Hills, a British tank commander, recalled what happened when his column was ambushed by a Tiger on 2 August 1944: [QUOTE] “…the [Typhoons] came in, very low and with a tremendous roar. The second plane scored a direct hit and, when the smoke cleared, we could see the Tiger lying on its side minus its turret and with no sign of any survivors.

” But the heavily defended intersections of inland France lay ahead. Nobody spoke it aloud, but every pilot understood: this would be one of the hardest runs since D-Day. The morning briefing carried a weight all its own. Reconnaissance photos lay across the table, cold and clinical.

A lattice of tracks converged on Falaise, sidings jammed with fuel wagons and ammunition cars. Over 40 flak positions ringed the target, the inner defenses bristling with radar-guided 88-millimeter guns. On the dispersal line, Typhoons crouched beneath eight RP-3 rockets and full 20-millimeter belts. The extra ordnance added more than 1,200 pounds, weight that dulled agility and climb.

Rocket rails dragged at top speed. Overcast skies offered concealment, but the hidden landmarks forced navigation by compass and gut instinct. Falaise emerged from the haze. The rail yard sprawled below them, smoke curling from earlier strikes. Then the flak opened. Black puffs of 88-millimeter fire blossomed at 3,000 yards.

The Typhoons shuddered as fragments ripped at wings and fuselage. The shorter bursts of 40-millimeter Bofors and 20-millimeter cannons stitched the sky with flashes. Approaching from the southwest, pilots dove at 420 miles per hour, air screaming past the canopy. White rocket trails arced across the maelstrom, bracketing moving targets with pinpoint timing.

Within seconds, pilots calculated range, wind, and target speed, firing pairs and singles in rapid succession. During the pullout, chaos filled their cockpits. Concussion waves rocked the fuselage, shrapnel pinged against armored glass, and cylinder temperatures spiked as Sabre engines strained.

The stick shuddered in the pilots’ hands, every control heavy and sluggish, G-forces slamming them into their harnesses. Compressibility buffeted the wings past 500 miles per hour, shaking the airframe and testing every ounce of skill. But the run was a success. The Falaise strikes left the Germans reeling.

Ammunition depots and marshaling yards burned. Tracks twisted under rocket impact, tanks rendered immobile. Typhoons had not just attacked—they had shredded the infrastructure of resistance, carving a corridor for the Allies to push deeper into France. The liberation of Paris in August 1944 shifted momentum, but German resistance stiffened as Wehrmacht units fell back toward the Rhine.

Typhoon squadrons adapted quickly, shifting from close support to exact strikes on command and logistics networks. Ultra intelligence revealed the locations of headquarters and staff officers, allowing Typhoons to hit key targets with devastating effect. RAF Second Tactical Air Force Typhoons, loaded with armor-piercing RP-3 rockets, dove on enemy buildings.

Within minutes, headquarters were reduced to smoldering ruins, valuable officers buried with them. Communications got shredded, and operations paralyzed for days. German commanders scrambled, moving HQs underground or dispersing staff, making coordination even more fragile through the war’s final months. In March 1945, Operation Varsity—the massive Allied airborne assault across the Rhine—put Typhoons to their next test.

Over 1,700 transports and gliders carried two divisions behind German lines. Typhoons suppressed radar-directed 88-millimeter guns along the Rhine, attacking low to avoid detection yet within range of light AA fire. Rockets tore through emplacements, scattering crews and neutralizing defenses. Over 400 sorties delivered paratroopers, often with pilots flying six missions a day while ground crews refueled and rearmed in near-assembly-line fashion.

By April, Group Captain J.R. Baldwin scored his 15th and final Typhoon victory. Pilots were credited with roughly 246 enemy aircraft destroyed—an extraordinary record for a primarily ground-attack plane. Victory in Europe Day arrived on May 8, 1945, but Typhoon squadrons faced uncertainty.

The RAF rapidly demobilized; aircraft that had been indispensable months earlier became surplus. By October, squadrons disbanded, Typhoons scrapped, and the Napier Sabre engines dismantled. Despite this, the Typhoon’s impact endured. Its constant attacks in Normandy disrupted German counterattacks, accelerating the breakout. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt later called Allied air power, particularly rocket-equipped aircraft: [QUOTE] “Absolutely decisive.

” Sydney Camm learned the hard way with the Typhoon—thick wings, compressibility quirks, and an engine that could bite back. Those lessons shaped the Hunter: thin, swept wings and a sleek airframe built to slice cleanly through transonic flight. With the Harrier, Camm went further—rugged, simple airframe wrapped around the radical Pegasus vectored-thrust engine.

Wrestling the Napier Sabre taught him how to harness raw power without letting it destroy the aircraft. From Typhoon to Hunter to Harrier, Camm’s genius was clear: build tough machines around brutal engines, and push the limits. Today, only one Typhoon remains, displayed at the RAF Museum in Hendon, North London.

News

Have you come to scold me, mother-in-law? Wasted effort. Your son is a traitor and a cheat, and this apartment is my legal property and mine alone.

“Are you kidding me or what?” Sasha’s voice rang like a tight string. “I came home and you didn’t even…

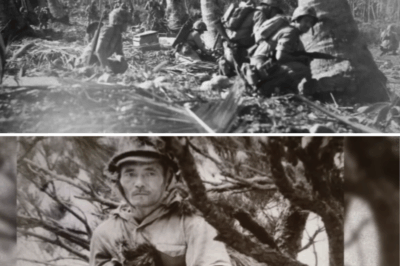

CH1 Engineers Called His B-25 Gunship “Impossible” — Until It Sank 12 Japanese Ships in 3 Days

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1942, Captain Paul Gun crouched under the wing of a Douglas A20 Havoc at…

CH1 They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

CH1 How a Farm Kid’s ‘INSANE’ Trick Shot Down 37 German Planes — Saved 300 Bomber Crewmen

At 0847 on the morning of October 14th, 1943, Staff Sergeant Raymond Sullivan watched a formation of 291 B7 bombers…

CH1 German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them

April 8th, 1943. 27,000 ft above Kong, France. The oxygen mask couldn’t hide Oberloitant Ralph Hermachin’s smirk as he watched…

CH1 How One Marine’s ‘INSANE’ Aircraft Gun Mod Killed 20 Japanese Per Minute

September 16th, 1943. Tookina airfield, Buganville, Solomon Islands. Captain James Jimmy Sweat watches his wingman die. The F4U Corsair spirals…

End of content

No more pages to load