The war had ended in Europe, but the prisoners carried their pride with them across the Atlantic. In June 1945, transport ships unloaded thousands of German soldiers onto American soil. They had been captured in France, in the rurer pocket, and even in Italy, and now they were herded through camp gates in Kansas, Texas, and Iowa.

Dust swirled around their boots, and their uniforms hung loose from weeks of rationing. Yet arrogance lingered, especially among the officers. One afternoon, when word spread that the Americans would feed them in something called a cafeteria, laughter erupted in the barracks. A lieutenant from Hamburg sneered that such a word could only mean a cheap tavern or a school child’s lunchroom.

Americans, he declared, know nothing of table ritual. Their meals are as childish as their films noisy, cheap, and tasteless. His comrades chuckled, adding that only in Germany was dining treated as an art, with dignity preserved, even in wartime. The irony, of course, was that many of them had not eaten a full meal in months.

Bread had been scarce, potatoes rationed, meat almost absent, yet pride was stronger than hunger. The memory of oak panled officer mesh halls lingered white tablecloths, sausages arranged neatly, wine bottles opened with ceremony. It was less about the food than the performance, the sense of hierarchy at the table.

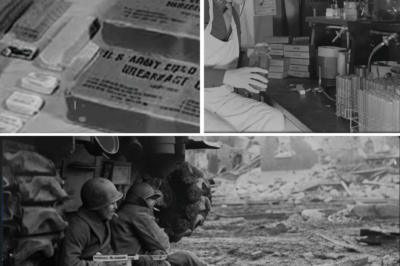

To the Germans, dining meant order and discipline, and they assumed the Americans had none. What they did not know was that by 1944, the US Quartermaster Corps had perfected a system that no army in history had ever matched. America could supply not just its soldiers on three continents, but also its prisoners. In that single year, American farms produced over 24 billion pounds of meat and flower mills churned out more than 120 million barrels of wheat.

Entire trains thundered across the Midwest carrying milk, vegetables, and sugar. It was not ritual that the Germans would encounter, but scale. Still, the prisoners laughed. They imagined tin cups and watered soup. Perhaps a slice of dry bread. A young private muttered that surely the Americans would make them eat like cattle. One pot, one spoon, no dignity.

Even hunger could not silence their smuggness. They believed America too crude, too brash to understand what a meal should mean. And so the stage was set, sneering prisoners, hollow with hunger yet wrapped in arrogance, about to walk into a place that would shake their confidence more than any battlefield defeat.

for behind those cafeteria doors under bright electric light was not humiliation but a revelation that would echo in their memories for decades. If you value stories like this, don’t forget to like and subscribe. It helps preserve forgotten chapters of history. And before we continue, share your location and local time in the comments.

It reminds us how history connects us across distance and generations. The first night in captivity passed with the usual mix of exhaustion and resentment. But as the prisoners awoke, they carried with them a curious pride rooted not in victory, but in memory. For what they missed most was not the battlefield, but the ritual of the German table in their minds.

Even the simplest military messaul in Germany carried an air of ceremony. There was order in every gesture the officers seated first. The folding of hands before eating, the measured serving of sausages and cabbage, sometimes even a small ration of wine. if fortune allowed. They remembered the sharp clatter of boots across polished floors, the smell of tobacco curling in the air, and the way silence was enforced until the senior officer lifted his fork.

It was more than food. It was hierarchy, discipline, and identity, even in defeat. These men clung to the belief that German meals were sophisticated, a reflection of a culture superior to the crude, noisy habits they imagined awaited them in America, in the barracks. The conversation circled endlessly.

A captain from Bavaria reminded younger men that the Americans think quantity is culture. He insisted that the Germans, even under bombs, had preserved the dignity of dining linen cloths when possible, toasts to fallen comrades, rules that made the table an extension of the officer corps. Food in Germany was scarce, but its scarcity gave ritual more meaning to him.

The act of eating was not just survival. It was a performance of pride. The younger prisoners listened, nodding, some thought of home, of mothers who laid out steaming potatoes on chipped plates, of fathers who sliced bread with deliberate care. These memories carried an aura of superiority, a conviction that Germans had always eaten with more refinement than the Americans ever could.

The word cafeteria still tasted foreign in their mouths. They used it mockingly, as if describing a carnival booth. They could not imagine that within hours this pride would falter, that the careful rituals they remembered would crumble before something larger than etiquette. What they did not yet understand was that America’s strength was not in ritual, but in abundance, not in hierarchy, but in scale.

For the German PSWs, this would be the crulest twist of memory that the tables they longed for with their rituals and pride would suddenly feel small, almost fragile when confronted with the bright roaring democratic machine of an American cafeteria. And so they waited in line, their stomachs growling, still certain that they knew what it meant to dine with dignity, still unaware that the next door they would pass through was not just a messaul, but a mirror reflecting the true difference between two worlds.

The midday whistle blew across the camp, and the guards called the prisoners to assemble. Rows of weary Germans shuffled forward, boots scuffing against gravel, the sun glaring overhead. They followed the line, expecting some crude feeding trough, perhaps a pot of thin stew ladled into dented tins. Yet, as they turned the corner, what awaited them looked nothing like humiliation.

The cafeteria doors swung open, and the PS froze. Before them stretched a hall blazing with electric light, rows of polished tables gleamed beneath fluorescent bulbs, their surfaces spotless, their order precise. Along one side ran the serving line’s stainless steel counters, reflecting the heat rising from great pans of food.

Steam curled upward from trays of beef stew and mashed potatoes, while loaves of bread sat stacked higher than any prisoner had seen since the war began. The sight was cinematic, overwhelming, as if staged to shock men who had lived in shadows. Green beans glistened under lamps. Cakes were arranged neatly in rows. Pictures of milk and coffee stood ready, waiting to be poured.

The air itself carried the warmth of roasted meat and baked sugar. For a moment, silence fell among the prisoners, their arrogance faltering under the sheer sensory force of abundance. A young corporal whispered, “This This is for prisoners.” Another soldier, barely 20, blinked rapidly as though fearing the vision might vanish. Their eyes darted to the guards, half expecting laughter or a trick.

But the Americans simply gestured toward the trays, impatient and business-like, as though this mountain of food was ordinary, nothing remarkable at all. The contrast was devastating, only months earlier. Some of these same men had stood in Berlin’s ration lines, waiting for a scrap of bread or turnup soup, now in captivity.

They faced more food in a single glance than they had seen in weeks. The polished trays reflected not just steam but an image of America itself industrial might translated into sustenance. Power measured in calories and cups of milk behind them. A Luftwaffa sergeant clenched his jaw unwilling to let his men see awe in his face.

But even he faltered as the line moved forward and the clatter of steel trays rang in the air. For in that moment, the proud rituals of German dining, the sausages and wine, the toasts and silence seemed almost quaint, fragile against the scale of this glowing hall, the men stood on the edge of something more than hunger. They stood before a revelation.

And as they stepped across the threshold, the first to take hold of a shining American tray, they realized that what they had mocked only hours before was about to strip away the very pride they had carried across the ocean. The line shuffled forward, each step echoing against the spotless tile floor.

The guards handed out trays, cold steel in their hands, and pointed toward the counters. What happened next would bewilder the Germans more than any weapon they had faced on the battlefield. There was no single pot into which food was dumped. No officer barking orders. Instead, they saw an orderly flow. Each man walked forward, slid his tray along the rail, and chose a spoonful of potatoes or not, beef stew or chicken, a slice of bread, then butter or jam if he wished.

The rhythm was mechanical yet strangely democratic, a production line of nourishment where each man became his own master. One prisoner muttered in disbelief, “We We may choose.” The guard simply nodded. Another P whispered, “Like American soldiers, the idea struck them harder than the smell of roasted meat.

Choice was a privilege they had not imagined for prisoners. In the Vermacht, rations were handed down without question. Eat what was given. No discussion. Here in captivity, they were confronted with the freedom to decide cornbread or biscuits, carrots or beans, coffee or milk. Some hesitated, as if reaching for too much might expose a trap.

A few looked back nervously at their comrades before scooping gravy onto their plates. But as the line moved, hesitation gave way to wonder. Trays filled, steaming and colorful, as though the very concept of hunger had been banished from this place. The irony was brutal. Back home, families in Hamburg and Cologne survived on meager slices of bread.

Children shared watery soup. Yet here, the defeated enemy could select between options and act so simple that it shook their notions of superiority. The cafeteria embodied something they had not prepared for abundance linked with liberty. Each tray was a silent lecture, a demonstration that in America even prisoners could exercise choice, dignity, and fullness.

It was democracy translated into food, a weapon without gunpowder, no less devastating than artillery. As they sat down, forks clattering, the PS glanced at one another with uneasy expressions, pride and disbelief tangled in their throats. One whispered, “We thought they would humiliate us.

But what is this?” if not humiliation of a different kind. For the first time, the laughter that had filled the barracks was gone. In its place came the quiet confusion of men forced to see freedom not in speeches or banners, but in the steaming haze rising from their own plates. The first bites silenced the room.

Forks scraped gently against trays as the men tasted what they had mocked hours earlier. A private from Bremen, who had not tasted meat since the winter of 1944, closed his eyes as Stew coated his tongue. Another, skeptical of the pale spread called peanut butter, dipped bread into it. grimaced, then smirked as he reached for more.

The initial snears dissolved into hurried chewing, eyes darting to see who would admit it first. Within minutes, the order of the line broke down. Men who had finished their portions rose awkwardly, trays still clutched in their hands and drifted back toward the counters. The guards looked on with faint amusement as the same Germans who had laughed at American cafeterias returned for seconds.

One Luftwafa officer muttered to his comrade. In Germany, even civilians starve. Here, even captives eat their fill. His words spread quietly, repeated like a confession across the tables. The atmosphere shifted. The first meal had been shock. The second helping became surrender of pride. A sergeant who once lectured on the refinement of German dining now shoved cornbread into his mouth with boyish hunger.

A young private licked frosting from his fingers, whispering that it tasted sweeter than any ration his mother had stretched across a month. In the barracks later that night, men laughed nervously, not at the Americans, but at themselves how quickly hunger had defeated their arrogance. Yet gossip festered as well.

Some muttered that the abundance was a trick, that Americans staged this bounty to weaken German resolve. Others claimed that the US wasted food while Europe bled and that such waste was proof of decadence. But for most, the memory of that first cafeteria meal would not fade because it filled not just their stomachs but their imagination.

What they did not know was that US agriculture had reached unprecedented scale. In 1945 alone, American farms produced over 55 billion quarts of milk, and sugarbeat fields stretched across the Midwest like oceans of white. The cafeteria was not a performance. It was the byproduct of a system that dwarfed anything in Europe. To the prisoners, every slice of cake and every glass of milk was proof that the war had been lost long before they surrendered.

That night in the barracks, the men argued, “Was America strong because of its weapons or because of its food?” “Could an empire built on abundance be beaten by one that glorified discipline?” A captain stared at the ceiling in silence, unable to answer. “And here, dear viewer, is where I ask you directly, if you had been one of those men, stripped of pride and hunger alike, what would have broken you first, the enemy’s guns or his food? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

Because history is not just about armies. It is about the taste that lingers after the battle ends. By the second week, the cafeteria had become routine, but the shock had not faded. Each day, the prisoners filed in, trays clattering, steam rising, choices unfolding like a quiet parade of plenty. The arrogance that once wrapped their shoulders like a cloak had thinned, thread by thread, until even the proudest among them stood quietly in line.

One Luftwafa captain, known for his clipped orders and disdainful gaze, was spotted slipping back into line for seconds. His men watched in silence, a mixture of relief and discomfort settling in their eyes. Pride was hard to maintain when roast beef, coffee, and cornbread sat waiting only a few steps away. Another officer, who had once lectured the barracks on American vulgarity, now held his tray close to his chest, balancing two slices of pie with care. Nobody mocked him.

Hunger had united them more effectively than rank or ideology. But there was another layer to the cafeteria experience that unsettled them even more. Behind the counters stood not just white American cooks, but African-American mess workers and sometimes women in uniform serving prisoners with a matter-of-act efficiency.

for men who had been fed propaganda about racial hierarchy. The moment was shattering, to be handed food respectfully, silently by someone whom their Reich ideology had condemned as inferior shook them more deeply than they admitted aloud. Whispers spread in the barracks that night. Some muttered shame, others deflected, claiming it was just America’s way.

But the silence of the officers told its own story. The cafeteria was not only a place of abundance, but a daily reminder that the world they had believed in order, ritual, superiority was collapsing with every spoonful of stew. Statistics sharpened the humiliation. Each camp cafeteria could serve thousands of meals within an hour.

Conveyor belt efficiency matched with industrial might at Camp Swift in Texas alone. Records show that over 20,000 lbs of flour were baked into bread each week. The numbers were staggering, relentless, undeniable. Where Germany struggled to feed its children, America fed its prisoners as if scarcity did not exist. As the trays clattered and the line moved forward, many PS found themselves lost in thought.

What did it mean to be fed so well by an enemy? Was it kindness or domination dressed as mercy? A young corporal admitted in his diary that he feared the food more than the barbed wire because it made him forget his hatred. And so audience, I pose the question to you if your captor treated you not with cruelty but with abundance. Would your loyalty to your old beliefs hold firm or would each meal weaken it? Spoonful by spoonful, share your reflections.

Because in that question lies the hidden weapon of America’s cafeterias. Autumn sunlight slanted across the camp when the cafeteria doors opened once more. By now the ritual was familiar. The shuffle of boots, the gleam of trays, the rising steam of food. Yet something deeper had shifted. What began as laughter had turned to awe, then to uneasy acceptance.

Now it lingered as memory being etched into the very marrow of men who had once sworn allegiance to the Reich. A gray-haired officer, once a veteran of the Eastern Front, sat quietly at a corner table. He held his tray as though it were a relic. Before him lay mashed potatoes, green beans, and a slice of chocolate cake.

He ate slowly, almost reverently, as if each bite carried the weight of a lesson he could not escape. Later, in the barracks, he whispered to a comrade. They win not only with guns, but with their ability to feed even us. We were wrong to laugh. The cafeteria had become a symbol, a theater of abundance. Its very mechanic steel trays sliding across rails, milk jugs clinking, loaves of bread stacked endlessly testified to something greater than taste.

It was industrial democracy in motion. A machine built not just to fight, but to nourish. For the Germans, it was impossible to ignore that such power made their once proud rituals of wine and sausages feel like echoes from another century. Stories spread beyond the camp fences. Some prisoners wrote letters home, careful with censorship, hinting that captivity was less brutal than feared.

Others remained silent, ashamed that their most haunting memory of war was not gunfire or bombings, but the abundance of an enemy cafeteria. The irony cut deep. The Reich had promised supremacy. But the lesson they carried home was the humiliation of second helpings. Years later, when the war was long past, these memories resurfaced.

Old men, now grandfathers, spoke less of battlefields and more of meals. A former soldier told his grandson not of tanks or artillery, but of the day he mocked a cafeteria, and then stood in line for seconds. His voice trembled as he described the clatter of trays, the flood of milk, the sweetness of American cornbread.

That image, more than the crack of rifles, had revealed the scale of America’s true power. And so the story closes not with thunder or fire, but with a quiet, lingering picture, a shining steel tray piled with food under the hard glow of electric light. For the prisoners who once scoffed, it was a weapon stronger than canon.

A lesson carried across oceans and through decades that abundance itself could break the walls of pride more surely than any bomb. History often teaches us through noise the roar of cannons, the thunder of engines, the shouts of armies in the field. Yet sometimes its deepest lessons come quietly in the clatter of trays and the steam of food drifting through a hall.

The story of German prisoners who once mocked American cafeterias only to stand humbly in line for second helpings reminds us that power is not always expressed in violence. Sometimes it is revealed in the simple ability to nourish, to sustain, to provide without fear of scarcity for the men who lived it. The cafeteria became a memory sharper than battle.

It stripped away layers of pride and revealed how fragile ideology can be when confronted with ordinary abundance. The Reich had promised them supremacy, discipline, and order, but it could not fill their stomachs. America, with its vast fields and tireless factories, offered something their homeland could not, a vision of plenty so vast it extended even to enemies.

In later years, when those prisoners returned home, many carried this paradox within them. They had been defeated in war, yet fed in captivity, they had laughed at the thought of eating like children, yet found dignity in choosing their own meals, and in the stillness of old age, when memories of war blurred.

It was not always the battlefield they spoke of, but the cafeteria. An old soldier once said that he could still hear the sound of trays sliding along the rail decades after the war had ended. To him, it was the echo of a truth he could never forget. That strength is not only measured in weapons, but in the quiet, relentless power of a society able to feed even its foes.

News

CH1 German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted the Army That Never Starved

December 17th, 1944. The frozen earth of the Arden’s forest crunched beneath Vermach boots as German officers surveyed their latest…

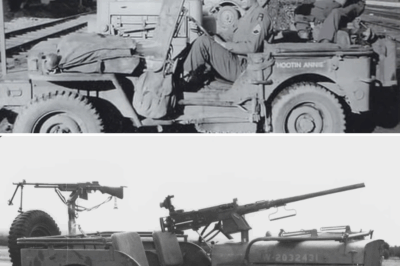

CH1 How the American Jeep Shocked the Germans on D-Day

June 7th, 1944, near smellers Normandy, Oberator, Klaus Miller of the 709th Infantry Division stared in disbelief at the column…

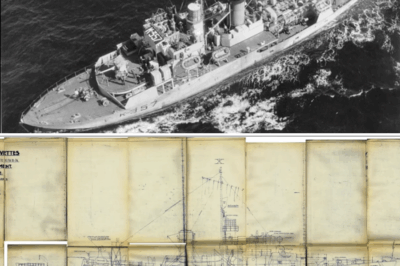

CH1 Why British Corvettes Cost 1/10th of a Destroyer — But Sank More U-Boats

March 1940, Britain’s accountants were calculating how long the nation could survive, and the numbers told a story more frightening…

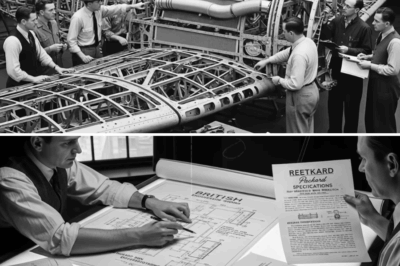

CH1 THE P-51’S SECRET: HOW PACKARD ENGINEERS AMERICANIZED BRITAIN’S MERLIN ENGINE

August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside Packard Motorcar Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant, two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines roared to life…

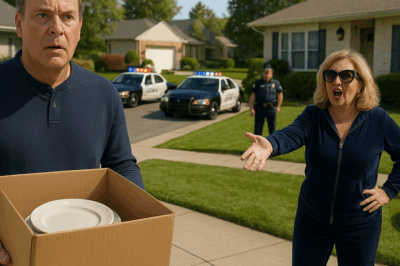

HOA Called Cops When I Moved Out of the HOA — Lost It When She Learned I Bought the Entire Block

She dialed 911 the moment I packed my first box. “He’s abandoning the rules,” she shrieked into her phone, her…

My Parents Wanted Me To Support My Sister Marrying My Ex-Husband & Took His Side—So I Walked Away..

My parents wanted me to support my sister marrying my ex-husband and took his side. So, I walked away and…

End of content

No more pages to load