North Atlantic spring 1943. Corvette and Captain Hansom Schwank, commander of U43, breaks radio silence to report a convoy. Convoy cited. Position 52° 14 minutes north. 35° 42 minutes west. Course 270. Speed 7 knots. 40 ships. 14 seconds. Encrypted. Unbreakable Enigma cipher. In that instant, an invisible web lights up.

Bearings snap to life across Allied boards. Three stations, Iceland, Newfoundland, one destroyer at sea, grab his signal within seconds. Lines converge on plotting boards. A position fix, accurate within 5 km. Schwanka doesn’t know it yet, but he has 36 hours before the pattern becomes undeniable. before the mathematics of systematic detection prove what German doctrine refuses to believe.

April 1943, the Mid-Atlantic Black Pit. For 2 years, this gap had been Germany’s hunting ground, 700 m from Newfoundland, 800 m from Iceland, beyond the reach of land-based aircraft where Allied convoys crawled westward at 7 knots, exposed and vulnerable. The German Yubot arm called it a happy time. Admiral Donitz had perfected the Wolfpack doctrine.

8 to 12 submarines coordinated by radio, massing against slow convoys, attacking from multiple directions simultaneously. The escorts couldn’t defend everywhere at once. The mathematics favored the hunters. A convoy moved at 7 knots. A surfaced hubot could make 17 knots. The Ubot could outrun, outmaneuver, and overwhelm any escort screen through sheer coordination.

And coordination meant radio communication, position reports every 6 hours, convoy sighting transmissions, weather updates, tactical coordination messages. The entire Wolfpack system depended on boats talking to each other and to Yubot command headquarters in France. German Naval Command believed this communication was safe.

The Enigma cipher was mathematically unbreakable. Even if the Allies intercepted transmissions, they couldn’t read them. And even if they could read them, radio signals didn’t provide location information. That was basic physics. Radio waves radiated in all directions. You couldn’t determine where a transmission originated, or so German doctrine stated.

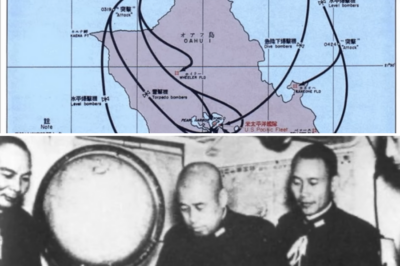

In late April 1943, Admiral Dernitz positioned two Wolfpacks, Groupupiser and Group, totaling 30 Ubot along the projected route of convoy NS 543 merchant ships departing Liverpool bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Course directly through the Black Pit. The convoy escort, seven warships, seven against 30. The mathematics were clear.

Schwanka commanded U43, part of groupies. His orders, coordinate with the Wolfpack, report convoy positions, mass for a night surface attack. Standard procedure. He’d done this successfully 17 times before. But April 1943 was different. The Allies had deployed a weapon the Germans didn’t fully understand.

Highfrequency direction finding. The British called it Huffduff. shore stations in Iceland, Newfoundland and Britain shipboard sets aboard every escort group, all monitoring German radio frequencies continuously. The system worked because physics worked differently than German doctrine claimed. When a yubot transmitted, shore stations and ships detected the signal and the antenna rotated until it found maximum signal strength.

That direction was a bearing, a straight line from the receiver toward the transmitter. One bearing gave a line. Two bearings gave a cross. Three bearings gave a position fix. And in April 1943, the Allies had HF/DF stations covering the entire North Atlantic. Convoy ONS5 entered the Black Pit.

On April 28th, Schwanka and 29 other Yubot commanders were waiting, ready to coordinate the attack. What happened over the next 7 days would change the Battle of the Atlantic forever. Highfrequency direction finding wasn’t new technology. The British had used radio direction finding in World War I, but by 1943, the Allies had perfected it into a weapon system.

The physics were simple. Radio waves travel in straight lines. When U43 transmitted, the signal radiated outward in all directions at the speed of light. An HF/DF receiver detected the signal. The operator rotated the antenna until the signal strength peaked. In that direction, that bearing was a straight line from the receiver to the transmitter.

The challenge was that one bearing only told you direction, not distance. The hubot could be 50 mi away, could be 500. But if two stations took bearings simultaneously, the lines intersected. That intersection was the hubot’s position. Three stations made it certain and the allies had built a network covering the entire Atlantic.

Shore stations operated continuously. Reikavik, Iceland, Argentia, Newfoundland, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, Bermuda. Each station monitored German radio frequencies 24 hours a day. When they detected a transmission, operators grabbed bearings and transmitted coordinates to the Admiral T in London within 5 minutes.

The Admiral T calculated the position fix and radioed escort commanders. Yubot transmission detected position 52° 14 minutes north, 35° 42 minutes west, time 08 47 hours. But shore stations alone weren’t enough. The Allies needed mobile detection platforms. So they installed HF/DF equipment aboard escort vessels, destroyers, corvettes, frigots.

Every escort group carried at least one ship with HF/DF capability. These shipboard sets provided the third bearing, the one that turned two lines into a confirmed position. The system worked because it was passive. HF/DF receivers didn’t transmit anything. They just listened. The Ubot never knew they were being detected, and the system was fast.

From transmission to position fix to orders, transmitted to escort groups, 5 to 10 minutes. But HF/DF was only the first layer. The Allies had integrated it with other detection systems. Centimetric radar, 10 cm wavelength, could detect a surfaced hubot at 12 km in darkness or heavy weather. Attic sonar tracked submerged contacts. Hedgehog mortars, forwardthrowing weapons allowed escorts to attack without losing sonar contact, and escort carriers provided air cover.

Aircraft forced Ubot to stay submerged, draining batteries, preventing coordination. The entire system worked because each component fed the next. HF/DF narrowed the search area. Radar found the surface contact. Sonar tracked the dive. Hedgehog delivered the kill. The Germans called it the Huffduff net. They knew it existed.

What they didn’t understand was its coverage, its accuracy, or its integration with other systems. Schwantki was about to receive a comprehensive education, and the tuition would be measured in Ubot. April 28th, 1943. 0847 hours. Schwanka’s transmission lasted 14 seconds. A tur report to Yubot command.

Convoy position, course speed, composition. In Rekuik, a British operator heard the signal. He rotated his antenna. Peak signal at bearing 195°. He marked his plot and transmitted to the Admiral T. Ubot transmission frequency 12,040 kHz, bearing 195° from Reiki time 0847. In Argentia, Newfoundland, a Royal Canadian Navy operator detected the same signal.

Bearing 087° transmitted to Admiral T aboard HMS Duncan, a destroyer escort 40 km from the convoy. The radio operator heard it bearing 342° reported to the ship’s commander, then transmitted to Admiral T. Three bearings converging on the plot. At the Admiral T submarine tracking room in London, Lieutenant Commander Roger Wyn marked the intersection.

Position 52° 16 minutes north, 35° 40 minutes west. Accuracy estimated at 4 km. Elapse time from transmission to fix 90 seconds. Wind transmitted to Commander Peter Gretton aboard HMS Duncan, escort commander for ONS5. Yubot transmission detected. Position 52° 16 minutes north, 35° 40 minutes west, 11 km ahead of convoy track.

Gretton received the message at 0852 hours, 5 minutes after Schwanki’s transmission. Gretton made immediate tactical decisions. First, alert all escorts. Ubot ahead of the convoy, preparing an attack position. Second, vector support group B7 to intercept. Three destroyers and one frigate currently 60 km northwest. Course 045°.

Speed 28 knots. Estimated intercept time 2 hours 15 minutes. Third launch aircraft from escort carrier HMS Biter. Search pattern centered on HF/DF fix position. The convoy maintained course and speed seven knots west. The escorts formed anti-submarine screen, but the hunters weren’t the escorts anymore. The hunters were the support groups, racing toward mathematically derived intercept positions.

Schwank didn’t know he’d been detected. He remained on the surface, charging batteries at 15 knots, moving to a forward attack position. He was waiting for other Wolfpack boats to report positions so they could coordinate a multi-directional attack after sunset. Standard Wolfpack doctrine. He’d executed it 17 times successfully.

At 0920 hours, 33 minutes after Schwanki’s transmission, a Swordfish aircraft from HMS Biter spotted a surfaced Hubot. Position 52° 18 minutes north, 35° 38 minutes west. Distance from HF/DF is 3 km. The pilot attacked immediately. U43 crash dived. The depth charges missed. Schwanki had seen the aircraft early, dove fast, but the attack forced him deep, interrupted his battery charge, disrupted his positioning.

More importantly, it confirmed the system worked. From transmission to aircraft contact, 33 minutes. The invisible net had closed. Schwank just didn’t know it yet. 6 hours after Schwank’s first transmission, 1450 hours. The weather deteriorated. Wind force 7. Heavy seas. Visibility dropped to 3 km.

For Ubot, heavy weather has always been an advantage. Surface radar performance degraded in rough seas. Visual detection became nearly impossible. Escorts had to reduce speed in high waves, losing their speed advantage. But heavy weather also forced Ubot to surface more frequently. Submerged boats in rough seas rolled violently.

Crews became exhausted quickly. Battery drainage increased. The boats had to surface to recharge more often than in calm conditions. The Wolfpack needed to coordinate, and coordination meant communication. Between 1450 and 1630 hours, a 90-minute window, five Ubot from Group Misa transmitted position updates, five transmissions, five HF/DF fixes, five positions plotted at the Admiral T.

The pattern was now clear to Commander Win in London. Eight Ubot including Schwanki’s U43 formed a loose arc north and west of convoy ONS5. The classic Wolfpack deployment strung along the convoy’s projected track, ready to converge for coordinated night attack. Wind transmitted the complete tactical picture to Gretton. Gretton coordinated the Allied response.

Support group B7 moved northwest, positioning to block the most likely Yubot approach routes. HMS Biter’s aircraft maintained continuous patrol over the suspected hubot positions. Escorts equipped with 10 cm radar move to the convoys flanks. Their mission, detect surfaced hubot attempting to charge batteries or move into attack positions.

The integration of HF/DF and radar created a lethal combination. HF/DF narrowed the search area to a box 20 km on each side. Radar could detect a surfaced hubot at 12 km, well within the HF/DF box. At 1705 hours, HMS Videt detected a surface contact, range 11 km, bearing 285°. Videt increased speed to 24 knots. At 1721 hours, at a range of 4 km, the Hubot detected the destroyer’s approach and crash dived. Too late.

Videt’s Azdic operator gained solid sonar contact at 1,200 m. Depth 60 m, speed 4 knots. Course steady. Videt’s captain positioned for the hedgehog attack. The forwardthrowing mortar system launched 24 projectiles in an elliptical pattern 230 m ahead of the submarine’s position. The projectiles parked through the air, splashed into the water, and sank.

Three detonations, contact hits. At 1734 hours, debris surfaced, oil slick spreading, pieces of wooden decking, a life jacket. U258 destroyed. Schwank was 40 km away, submerged, conserving battery power. He heard nothing. But at 1900 hours, when U258 failed to make its scheduled transmission, he noted it in his log.

Radio silence from a boat meant one of two things. Mechanical failure or death. April 29th, 1943. 0245 hours. 22 hours since Schwank’s first transmission. Night. The traditional time for wolfpack attacks. Ubot surfaced under cover of darkness. Attacked at close range. Used night as concealment. But 10 cm radar changed everything.

HMST detected a surface contact. Range 9,200 m, bearing 047°, moving slowly, likely charging batteries. TA’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Robert Sherwood, increased speed to 26 knots. Silent approach. The radar contact remained steady. The Yubot hadn’t detected the destroyer’s approach. At 0312 hours, range 2,800 m, the yubot dove.

The watch officer had finally spotted TA’s silhouette. TA’s Azdic operator gained contact immediately. Target depth 40 m, speed 5 knots. Course 175°. Sherwood positioned for the Hedgehog attack. Hedgehog’s advantage over conventional depth charges was simple. The contactfused projectiles only detonated on direct hit.

If they missed, they sank silently to the ocean floor. No explosions to blind sonar. No loss of contact. TA’s Hedgehog fired at 03 27 hours. 24 projectiles splashed ahead of the submarine’s predicted position. 4 seconds later, two detonations. At 03 29 hours, a massive underwater explosion. The submarine’s pressure hull imploding under depth pressure.

U386 destroyed from radar contact to confirm the kill in 17 minutes. Schwanki surfaced at 0430 hours. He needed to charge batteries down to 40%. He maintained strict radio silence, no transmissions, just charging. No destroyers appeared, no aircraft, no contacts. He submerged at 0630 hours after 2 hours on the surface. batteries at 70%.

Enough for another submerged day. But he’d noticed something. U386 had transmitted a position report at 1507 hours the previous day. At 0400 hours, 11 hours later, Schwanki heard distant underwater explosions. The direction matched U386’s last reported position. One boat transmits. 11 hours later, destroyed. U258 transmitted at 1451 hours, destroyed at 1734 hours, 3 hours.

Schwanki pulled out his chart. He marked every transmission time from the previous day, then marked every explosion he’d heard or boat that went silent. The correlation was absolute. Every boat that transmitted was contacted by Allied forces within hours, usually within 30 minutes to 2 hours. Boats that maintained radio silence like U43 after the first transmission weren’t contacted.

The variable was clear. Radio transmission equal detection. But how? Enigma was unbreakable. Radio direction finding from shore stations couldn’t be that accurate. There had to be shipboard detection mobile platforms that could triangulate positions in real time. Schwanki understood the implications immediately. Wolfpack doctrine.

Coordination through radio had become a death sentence. Every position report painted a target. Every weather transmission gave away location. Every coordination message summoned hunters. The system that made wolfpacks effective had become the system that killed them. April 29th, 1800 hours. 36 hours since Schwanka’s first transmission.

Yubot command transmitted orders to all group Amisa boats. Report positions immediately for coordinated night attacks. It was a direct order. Disobeying meant court marshal. Between 1800 and 1845 hours, 12 Ubot transmitted positions. Schwank monitored the radio frequencies. He heard each transmission. 14 seconds, 18 seconds, 22 seconds.

Brief, encrypted, professional. The Admiral T’s HF/DF network captured all 12 transmissions. Within 40 minutes, Commander Wyn had a complete tactical picture. He transmitted positions to all escort groups. Commander Gretton didn’t wait for the Ubot to attack. He went on offense.

Escorts moved directly toward HF/DF positions. Support groups positioned to cut off retreat routes. Aircraft from HMS BER launched for night patrols. Between 2,000 hours, April 29th, and 0400 hours, April 30th, Allied forces made contact with six different Ubot. U613, forced to dive by destroyer, depth charged, damaged, forced to abort patrol.

U415, contacted by aircraft, bombed, with moderate damage. U84 engaged by a support group, severe depth charge damage, sinking. U630 contacted by escorts using HF/DF fix hunted for three hours. Sun sunk by hedgehog U264. Forced deep by a destroyer. Battery exhausted. Forced to the surface. Captured crew after scuttling.

Five boats contacted. Three destroyed or captured. Two damaged and forced to abort. None got into an attack position. Not one torpedo fired at the convoy. Schwanki heard it all through his hydrophones. Distant explosions, depth charges, the unmistakable sound of pressure hulls imploding. At 0600 hours, April 30th, he calculated the Wolfpack status.

April 28th, 30 boats operational. April 30th, 18 boats are still operational. Losses, six destroyed, six damaged and aborting. Time elapsed, 54 hours. The merchant ship sank zero. The mathematics were final. Wulpac grouper had achieved nothing. The convoy was escaping and the boats were dying one by one because they couldn’t stop talking. May 6th, 1943.

U43 returned to base at Laurant, France. Schwanka had maintained almost complete radio silence for the final week of patrol. Two transmissions total, both brief, both unavoidable responses to direct orders from Yubot command, no Allied contacts, no depth charges, no aircraft attacks. He’d survived by not talking.

Schwanki submitted his patrol report immediately. He detailed everything. the pattern of detections following transmissions, the correlation between radio communication and allied response times, his conclusion that the allies possessed realtime direction finding capability. He recommended immediate revision of Wolfpack doctrine, minimize radio transmissions, coordinate through pre-arranged positions rather than radio updates, and accept reduced coordination efficiency in exchange for reduced detection risk.

The response from Yubot command came 3 days later. His observations were noted. His recommendations were under review. Continue following standard communication procedures. But Schwanka knew the truth would emerge in the statistics. May 1943 became Black May in the Marine Corps. 43 Yubot sank. Over 1,000 submariners killed.

One quarter of the operational fleet was destroyed in 30 days. On May 24th, Admiral Donitz ordered all Ubot to withdraw from the North Atlantic convoy routes. The Battle of the Atlantic was effectively over. Postwar analysis confirmed what Schwanka had discovered in April 1943. The Allied HF/DF network had achieved comprehensive coverage by early 1943.

Detection rate 95% of all Hubot transmissions. Position accuracy 5 km average. German Ubot losses from April to May 1943, 76 boats, approximately 60% were detected via HF/DF before being destroyed by radar, sonar, and hedgehog. The invisible weapon had worked exactly as designed. Radio waves had become kill orders.

Communication had become death. and the Wolfpack doctrine built on coordination had collapsed because coordination required talking and talking meant dying. This story is based on documented HF/DF operations during the battle around convoy April 28th to May 5th 1943. Corvette and Captain Hans Yakim Schwanka commanded U43 and survived the war.

The six yubot losses, detection patterns, and systematic methodology are verified through British Admiral Ty records, German war diaries, and convoy action reports. The invisible net had worked not through firepower, but through mathematics. Subscribe for more enemy POV technology and consequences. Thank you for reading.

News

My Parents Put $12,700 On My Credit Card For My Sister’s “Luxury Cruise Trip.” When I Called, My Mom Laughed, “It’s Not Like You Ever Travel Anyway.” I Just Said, “Enjoy Your Trip.” While They Were Away, I Quietly Sold The House They’d Been Living In Rent-Free. When They Came “Home”…

It’s not like you ever travel anyway, Holly. Stop being so dramatic about this whole situation right now. My mother’s…

CH1 The Secret German Fighter That Could Have Won WWII

Hotbus, Germany. January 1945. Kurt Tank stood beside his latest creation as the ground crew completed final preparations. The TAR…

CH1 Japanese Destroyer Captain Faced American Radar Guided Night Fighting Lost 4 Ships in 90 Minutes

August 6th, 1943, 11:30 p.m. Velf, Solomon Islands. Commander Kaju Sugura stood on the bridge of the destroyer Shigur, scanning…

CH1 Admiral Genda Shocked When He Realized The War Was Lost In Just 6 Months

September 1941, Major General Minoru Jenda stood before the Imperial Japanese Navy’s war council with absolute confidence. The plan was…

CH1 German Engineer Watched Americans Build 60-Meter Bridge in 8 Hours

March 1945, East Bank of the Rine, Germany. Hedman Klaus Bergman peers through his binoculars. On the opposite bank, American…

CH1 The “Das Boot” U-Boat Commander Hunted by Allied Radar – 43 Subs Lost in One Month

May 1943 breast France Capitan Zor Hinrich Layman Villinbrock stood at the window of his office overlooking the submarine pens…

End of content

No more pages to load