For 80 terrifying days, London was on the brink of collapse under the V-1 buzz bomb attacks. What the public never knew was that their salvation came from a tiny American invention that German physicists had already declared scientifically impossible. This is the story of that weapon, the American VT fuze, and how a tiny device, no bigger than a man’s hand systematically dismantled Hitler’s campaign of terror and saved London from utter devastation.

And the most remarkable part? The Germans never saw it coming. Our story truly begins just one week after D-Day, on June 13th, 1944, as Allied troops fought their way through the hedgerows of Normandy. Hitler unleashed his promised vengeance weapon, the V-1, at 4:15 in the morning. The first one slammed into a railway bridge in London.

The blast killed six people, injured 30 and left 200 homeless. It was a terrifying announcement that a new phase of the war had begun for the German high command. The V-1 was a source of immense pride. It was the world’s first cruise missile, a technological triumph years in the making. It carried nearly a ton of high explosives and flew at 400mph.

German leadership believed this weapon would finally break the will of the British people. Major General Walter Dornberger, the head of Germany’s advanced weapons program, had done the math. Even if only a quarter of the missiles got through. They would deliver more explosive tonnage to London than the entire Blitz of 1940 and 41.

And they could do it for a tiny fraction of the cost of a manned bomber with zero risk to their pilots. The scientists at the Peenemünde Army Research Center had every reason to be confident. They were the minds behind the world’s most advanced rocket and jet technology. Dr. Robert Lusser, the V-1 designer, had calculated that interception was a statistical impossibility.

The missile was simply too fast and flew at altitudes that made it a nightmare for Allied fighters to even have a chance. A British pilot had to push his plane to its absolute limits, dive down on the V-1 and get within 200 yards close enough to be obliterated by the explosion if he was successful. If stories like this about the hidden genius that won the war are important to you, a quick click on the like button tells us to make more of them.

But what about the anti-aircraft guns ringing the British coast? Well, German ballistics experts had calculated the odds of a direct hit on such a small, fast moving target at less than 1 in 10,000. Think about that for a moment. For every 10,000 shells fired, they expected only one to hit its mark. This wasn’t propaganda.

It was the cold, hard reality of warfare. At the time, a traditional anti-aircraft shell used a time fuze. The gun crew had to spot the target. Their brand new radar systems had to calculate its speed, altitude and direction. And then they had to manually set a tiny timer on the shell itself to explode at just the right moment in its trajectory.

From the moment a V-1 was spotted, gunners had maybe 30s to do all of this perfectly. A split second error in timing, a slight miscalculation in speed, and the shell would explode in empty air completely harmlessly. The Germans knew this because they used the exact same technology themselves. They were certain the V-1 was invincible.

And for a little while they were right. The first few weeks of the V-1 assault were terrifying for the people of London. The sound of the pulsejet engine, a rough, sputtering roar that earned it the nickname buzz bomb, became a sound of pure dread because when that sound cut out, everyone on the ground knew the bomb was in its final dive and they had only seconds to pray it wouldn’t land on them.

However, back in France, unsettling reports began to trickle into German intelligence. The British were adapting with an almost unnatural speed. By the end of June, the interception rate had rapidly climbed from around 24% in the first week to over 60%. This was higher than they had predicted, but their scientists reasoned it was possible.

Perhaps the British had better radar or more disciplined gun crews. It was explainable. But then came July and the numbers stopped making any sense at all. German observers started reporting something truly bizarre. They saw V-1s flying perfectly straight and level, suddenly erupt in a ball of fire. But the anti-aircraft bursts weren’t direct hits.

The shells were exploding near the missile. Sometimes 50 or even 100 ft away. Yet the V-1s were tumbling out of the sky as if they’d been hit by a sledgehammer. At the same time, intelligence analysts noted that British gun batteries were reporting an impossibly low number of shells fired for every V-1. They claimed to have shot down.

It was as if every British gunner had suddenly become the world’s greatest marksman overnight. Oberst Max Wachtel, the commander of the entire V-1 offensive, was alarmed. He suspected sabotage at the launch sites, or perhaps a flaw in the missiles themselves. He ordered emergency inspections, ran diagnostic tests, and even conducted test firings over German-held territory.

The results were always the same. The V-1s performed flawlessly. The problem, it seemed, only occurred when they were flying over the English Channel directly into the teeth of British defenses. The German leadership was forced to confront a deeply uncomfortable possibility. The Allies had developed some kind of revolutionary new weapon, but without a single piece of captured evidence, they had no idea what it was.

What they were facing was the technology born not in a single brilliant moment, but from years of quiet, relentless American ingenuity. It was called the VT fuze or variable time fuze. A deliberately misleading name meant to suggest it was just a better version of the old clockwork timers. The truth was far more radical.

It was a proximity fuze, a miniature marvel of electronics that contained its own tiny radio transmitter and receiver packed into the nose of an artillery shell. This little device sent out a continuous radio wave when the shell passed close to a target, like the metal fuselage of a V-1 bomb. The radio waves would bounce back and the receiver would detect the echo.

An electrical switch called a thyratron would then instantly trigger the detonator. In simple terms, the shell knew when it was close enough to do damage. It didn’t need a direct hit. A near miss was now just as deadly. This turned the entire equation of anti-aircraft warfare on its head. Instead of needing to hit a tiny target moving at 400mph, gunners just had to get a shell into the general vicinity.

The fuze did the rest. The very idea of this was something German engineers had already considered and dismissed as impossible. They had actually researched just over 30 different designs for a proximity fuze during the war, but every single attempt had failed. The technical hurdles just seemed too immense. First, you had to build a complete radio set transmitter, receiver, antenna and power source small enough to fit inside the tip of a shell.

Second, and this was the big one, you had to make it tough enough to survive being fired out of a cannon. The delicate vacuum tubes and glass batteries of the 1940s had to withstand forces of 20,000 times the force of gravity, and the spin rate of over 25,000 revolutions per minute. To German physicists, it was a laughable proposition.

It was like trying to build a grandfather clock out of fine crystal, then firing it out of a cannon and expecting it to still tell time. And yet, by the summer of 1944, American factories powered by the spirit of a nation at war were churning out 40,000 of these impossible devices every single day. The story of how this happened is a testament to the American way of war not just fighting on the battlefield, but winning in the laboratory and on the assembly line.

The project was handed to the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory under the direction of a brilliant scientist named Dr. Merle Tuve. He brought together the nation’s brightest minds from universities and corporations. It was a massive collaborative effort, the kind of thing America has always done best in times of crisis to solve the problem of the fragile vacuum tubes.

They turned to a company you might recognize. Sylvania Electric, their engineers took designs used for hearing aids with their tiny, delicate components and figured out how to reinforce them, encasing them in special wax and plastic to withstand the incredible G-forces. To power the device. They developed an ingenious glass battery that was kept inert until the moment of firing.

The shock of the shell leaving the gun barrel would shatter the glass vial, mixing the electrolyte and instantly bringing the battery to life. Every piece of the puzzle was a small miracle of engineering. This achievement wasn’t just about scientific genius, though, it was about industrial might. The scale of the American effort was something Germany simply couldn’t comprehend, let alone match.

The production of the VT fuze was spread across more than 110 different factories. It was so compartmentalized that most of the workers had no idea what they were actually building. One factory would make the batteries, another, the vacuum tubes, another the plastic casings. They just knew they were working on something vital for the war effort.

Companies that made refrigerators and radios before the war, like Crosley Corporation, completely retooled their assembly lines. At their peak, Crosley’s 10,000 workers, many of them women who had joined the workforce to support their husbands and sons overseas were producing 16,000 fuzes a day. It’s a detail many history books skip over, but if you agree these stories of the home front are just as important as the battles.

Consider subscribing so you don’t miss what’s coming next. The numbers tell a staggering story of two nations at war. While Germany was using forced labor from concentration camps to build its V-1. American workers were voluntarily putting in overtime. Driven by patriotism. By the end of the war, America had produced 22 million proximity fuzes at a cost of over $1 billion in 1940s money in a single month.

American factories produced more of these high-tech fuzes than the total number of V-1s Germany launched during the entire war. The German wonder weapon was being defeated not by another weapon, but by an entire industrial system. By the end of August 1944, the British had completely reorganized their defenses.

To take full advantage of this new American technology. They moved almost all of their anti-aircraft guns to the coast, creating what they called the Diver Belt. This was a genius move for two reasons. First, it created a concentrated wall of fire that every V-1 had to fly through. Second, it ensured that any shells that failed to explode would fall harmlessly into the sea.

Keeping the secret of the proximity fuze safe from German hands. Now picture that coastal gun belt. On that peak day in late August, a flight of V-1s cross the French coast. Their engines thrumming as they approach England. They are picked up by American-made SCR-584 radar sets. This wasn’t like old radar, where a man had to watch a blurry screen.

This new system automatically locked onto the target, calculated its speed and trajectory and fed that information directly to the guns, which would then automatically aim themselves. All the gun crews had to do was load the shells. And these weren’t just any shells. They were tipped with the VT fuze ready to turn the sky into a death trap.

As the V-1s entered the kill zone, the guns roared to life. Shells screamed into the air and instead of needing one lucky shot in 10,000, they just needed to get close. And they did. One after another, the shells’ tiny radios detected the flying bombs, and in a flash of light and a cloud of shrapnel, Hitler’s vengeance weapons were torn to pieces, plunging into the English Channel.

On that single day, 82% of the incoming missiles were destroyed. It was a level of effectiveness that, just weeks before, would have been considered a fantasy. For the Germans, it was a catastrophe. The 82% interception rate triggered crisis meetings at the highest levels. Wachtel was convinced it had to be sabotage.

How else could their wonder weapon be failing so spectacularly? But the frantic search for traitors and faulty parts turned up nothing. The only conclusion left was the one their own scientists had deemed impossible. The Allies had perfected the proximity fuze. They tried everything to counter it. They launched the V-1s at different altitudes, from treetop level to high in the stratosphere.

They sent them over in massive waves, hoping to overwhelm the defenses. They launched them at night and in bad weather. But nothing worked. The kill rate remained devastatingly high. The invisible shield held. The proximity fuze program was one of the greatest successes of the war. Not a single intact fuze fell into German hands during the entire V-1 campaign.

In a moment of supreme irony, during the Battle of the Bulge, German troops actually captured an entire American ammunition depot filled with crates of artillery shells equipped with VT fuzes. But because their own experts had declared such a device to be impossible, they never even thought to examine them.

They were holding the answer to their biggest mystery in their hands and simply didn’t recognize it. Blinded by their own scientific arrogance, the V-1 offensive, which was supposed to bring Britain to its knees, was effectively over by September 1944. Out of more than 9500 V-1 launched at Great Britain from the ground, only about 2500 ever made it to London.

While they caused tragic loss of life, killing over 6000 civilians, the number was a fraction of what the Germans had intended. General Frederick Pile, the head of Britain’s Anti-Aircraft Command, later estimated that without the proximity fuze, the casualties would have been at least four times higher. The little electronic device had saved tens of thousands of lives and may well have saved London itself.

After Germany’s surrender, Allied officers interrogated the men who had run the V-1 program. Their ignorance was total. Colonel Wachtel admitted. They suspected the British had better radar, but they never, ever imagined a shell that could think for itself. When German scientists were finally shown a captured American VT fuze.

They were in a state of disbelief. They couldn’t understand how the vacuum tubes could survive the launch or how the batteries could work. They looked at the sophisticated circuitry and admitted, with a sense of humiliation, that they were at least ten years behind American technology. Dr. Tuve, the American scientist who led the project, believed their success came from a uniquely democratic spirit of collaboration.

Scientists, engineers and factory workers all pulling in the same direction. It was a powerful contrast to the rigid top-down system of the German war machine. The proximity fuze proved that the outcome of the war was being decided in laboratories in Maryland and on assembly lines in Ohio, just as much as on the battlefields of Europe.

While Germany poured its resources into exotic, revolutionary wonder weapons, America was focusing on what are called multiplicative technologies—clever innovations that made existing weapons exponentially more effective. The VT fuze didn’t replace the anti-aircraft gun. It simply made every single one of them 5 to 10 times deadlier.

The change was dramatic. Before the fuze, it took on average, 2500 heavy artillery shells to shoot down a single V-1. With a fuze, that number dropped to just 100. It was a victory, one not through sheer bravery but through the mass production of a superior idea. On a scale Germany couldn’t begin to fathom.

The secret was finally declassified in August 1945, shortly after the end of the war. The official announcement from the War Department called it one of the most important weapons developed during the war. Surpassed in effectiveness only by the atomic bomb. For the German scientists who had been so baffled by their failures, it was a moment of shocking clarity.

They hadn’t been outfought. They had been out-thought and out-produced. They had lost not to soldiers, but to assembly lines. They had staked their hopes on a few perfect handcrafted weapons, while America had built millions of good-enough life-saving devices. Sharing this story with someone you know helps ensure that this incredible chapter of our history is never forgotten.

The legacy of the proximity fuze is all around us today, in the technology that powers modern air defense radar systems and countless other electronic devices. But its most important legacy was written in the skies over London in 1944. On that day, when 82% of Hitler’s terror weapons fell harmlessly into the sea, the nature of warfare had changed for good.

News

“Stop! You didn’t let my father into the apartment?” Igor asked his wife in surprise.

Lena slowly raised her eyes from the book she’d been reading, curled up in the corner of the sofa. Something…

Hearing that his parents were coming to visit, the rich man begged a homeless girl to play the role of his fiancée for just one evening.

And when she entered the restaurant, her mother couldn’t believe her eyes…” “Have you completely lost it?” she almost shouted,…

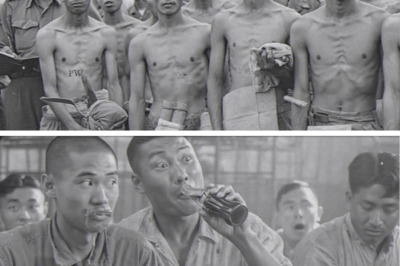

CH1 Japanese POWs Broke Down After Tasting Hamburgers and Coca-Cola in U.S. Camps

they were told Americans would torture them starve them and strip them of dignity but when Japanese prisoners stepped into…

CH1 What Japanese High Command Said When They Finally Understood American Power

August 6th, 1945, 08:15 hours. Imperial General Headquarters, Tokyo. A single decoded transmission from Hiroshima would shatter 3 years of…

CH1 Single American Sub Destroys Japan’s Largest Carrier! Archerfish vs Shinano 1944

She was a monster of steel, the largest aircraft carrier ever built. So secret that even most of Japan’s navy…

CH1 Japan Was Stunned When One U.S. “Destroyer Killer” Sub Sank 5 Ships in Just 4 Days

In the long dark history of submarine warfare, there is one rule that was never meant to be broken. You…

End of content

No more pages to load