June 7th, 1944, near smellers Normandy, Oberator, Klaus Miller of the 709th Infantry Division stared in disbelief at the column of American vehicles streaming inland from Utah Beach. In the span of 2 hours, he had counted 117 identical military reconnaissance cars, each one appearing as fresh as if it had just rolled off a factory floor.

What Miller witnessed that morning was not just an invasion, but an industrial phenomenon that would shatter every assumption the Vermach had made about warfare. These vehicles, which the Americans called jeeps, had crossed the Atlantic Ocean by the thousands, and their sheer numbers revealed a truth more devastating than any artillery barrage.

Germany was not fighting an army, but an entire industrial system that had transformed warfare into mass production. The jeeps had begun arriving with the first wave of landings driven directly off landing ship tanks that had crossed the English Channel in endless convoys. Each LST could carry up to 30 fully assembled jeeps and hundreds of these ships were delivering their cargo to the Norman coast.

The vehicles bore the markings of either Willis Oland Motor Company of Toledo, Ohio, or Ford Motor Company of Dearborn, Michigan. Their official designation read truck 1/4ton ton 4×4 command reconnaissance. But to the German soldiers watching them pour onto French soil, they represented something far more ominous.

Evidence of an industrial capacity that defied comprehension. Haltman Vera Linderman commanding the third company of the 919th Grenadier Regiment recorded in his afteraction report dated June 9th, 1944. The enemy possesses vehicles in quantities we reserve for ammunition rounds. Every American unit down to the squad level appears to have motorized transport.

We destroyed 12 of their reconnaissance cars yesterday. This morning, I count 40 in the same sector. They treat complex military vehicles the way we treat rifle cartridges as items to be used and discarded without thought. The statistics of American jeep production would have stunned German military planners had they known them. Between 1941 and 1945, American factories produced over 640,000 Jeeps.

At peak production, Willis Overland and Ford were completing one vehicle every 90 seconds on their assembly lines. This single vehicle type represented one quarter of all American military motor transport production. The Germans, who had managed to produce barely 50,000 cabal bargains during the entire war, could not conceive of such numbers.

What made this production miracle possible was a standardization that exceeded anything in German military experience. Every Jeep, whether built by Willis or Ford, used completely interchangeable parts. A transmission from a destroyed Ford GPW could be installed in a Willis MB in minutes.

Wheels, engines, axles, and even minor components like spark plugs and fan belts were identical across all production runs. This standardization extended to the supply system where spare parts were prepositioned based on statistical analysis of failure rates ensuring that replacement components were always available.

Feld Valhanrika of the 716th Static Infantry Division observing American operations from a concealed position near Karant wrote in his diary, “The Americans do not repair their vehicles. They simply replace broken parts with new ones from an endless supply. I watched a damaged vehicle restored to operation in less than an hour.

The engine was not repaired, but replaced entirely, unbolted, and lifted out with a fresh engine installed as casually as changing a tire. Our mechanics would require a week to perform such an operation. The Americans did it in a field under sporadic artillery fire while smoking cigarettes. The German military mind, trained in the tradition of preserving and maintaining every piece of equipment, struggled to comprehend the American approach.

In the vermachar, a vehicle was assigned to a unit and carefully tracked throughout its service life. Losing a vehicle through negligence was a court marshall offense. Mechanical problems were diagnosed with precision. Parts were carefully repaired or manufactured when replacements were unavailable. The Cubalva, Germany’s equivalent to the Jeep, required factory trade mechanics for any significant maintenance.

The Americans operated on entirely different principles. They had calculated that a Jeep’s combat life expectancy was 90 days and planned accordingly. Rather than investing in elaborate repair facilities, they simply manufactured replacements in quantities that exceeded any possible loss rate. When a jeep was damaged beyond immediate repair, it was stripped of usable parts and abandoned.

A new vehicle would arrive within hours or days, delivered by the endless convoys that connected the beaches to the advancing front lines. Lieutenant Colonel Otto Fon Schroeder, chief of staff of the 352nd Infantry Division, captured the German bewilderment in a letter to his wife. The Americans fight a rich man’s war. They expend vehicles the way we expend ammunition.

Yesterday, I observed a jeep strike a mine. The crew emerged unheard, transferred their equipment to another vehicle that appeared within minutes, and continued their mission. The destroyed Jeep was pushed to the roadside and forgotten. in our army. Such a loss would require reports, investigations, and weeks of effort to obtain a replacement.

By June 10th, American forces had landed over 12,000 vehicles in Normandy, with jeeps comprising the largest single category. These vehicles transformed the battlefield in ways German doctrine had not anticipated. American reconnaissance units penetrated German lines with unprecedented speed and flexibility.

Artillery, forward observers, and jeeps could rapidly relocate, making counter fire nearly impossible. Supply units maintained continuous contact with advancing forces, eliminating the pauses for consolidation that German commanders had expected to exploit. The Jeep’s capabilities compounded German difficulties.

With its four-wheel drive and low weight, it could traverse terrain that German planners had considered impossible for vehicles. The Norman Boge Country with its sunken roads and thick hedge should have channeled American vehicles into kill zones. Instead, Jeeps simply drove through fields over embankments and around obstacles.

They created their own road network independent of the mapped routes German forces had prepared to defend. Ust Hans Fonlook commanding a battle group of the 21st Panza Division wrote after the war, “The jeep gave every American unit the mobility we had, achieved only with our elite mechanized forces.

A single vehicle could carry a machine gun team, a mortar crew, communications equipment or supplies. They appeared everywhere in places we thought secure, bringing firepower or calling in artillery with their radios. We could not establish a continuous front because the Americans simply drove around our positions. The maintenance and supply system supporting these vehicles proved equally overwhelming.

American logistics units had prepared for operations on an industrial scale. Ships arrived daily carrying not just fuel and ammunition, but entire vehicles, spare engines, transmissions, and prepackaged component sets. Mobile workshops advanced immediately behind combat units capable of performing any repair or replacement.

If a unit lost 10 jeeps in combat, 10 replacements would arrive within 48 hours, often less. Major Henrik Zimmerman of the 12th SS Panza Division observed, “The American supply system operates like a factory production line extended to the battlefield. Everything is standardized, packaged, and delivered on schedule. They have removed the friction from warfare that Clauswitz described.

While we struggle to maintain our existing equipment, they simply order replacements as if from a catalog.” The psychological impact on German forces became evident within days of the invasion. Soldiers who had been told that Americans were soft and dependent on material comfort discovered an enemy who possessed material abundance beyond imagination.

The sight of endless columns of identical jeeps. Each one new and fully equipped demoralized troops who were carefully preserving vehicles that had been in service since the Polish campaign. Gret Wulf Gang Brown, a mechanic with the 21st Panza division, examined captured Jeeps and reported, “Every component is designed for mass production and easy replacement.

The engine is simple but adequate. The transmission is robust rather than refined. Nothing is polished or precisely fitted, yet everything functions reliably. They have sacrificed elegance for quantity, and quantity is winning the war.” The racial integration visible in American motorpools particularly troubled German observers indoctrinated in Nazi ideology.

African-Amean soldiers drove jeeps, maintained them, and supervised motorpools. This challenged fundamental Nazi assumptions about racial hierarchy and military effectiveness. Felval Kurt Vagnner noted with bewilderment, “Negro soldiers operate and repair these vehicles with the same efficiency as white soldiers.

Our racial theories suggest this should be impossible. Yet the evidence is undeniable. American modifications to their jeeps demonstrated a flexibility that German military culture could not accommodate. Within days of landing, units were welding additional armor plate, installing wire cutters to counter German piano wire traps, mounting multiple machine guns, and adapting vehicles for specialized roles.

Medical units converted jeeps to ambulances by installing stretcher racks. Signal units loaded them with radio equipment. Engineers mounted mine detectors. Each modification was crude by German standards, but immediately effective. The contrast with German equipment became increasingly stark as the campaign progressed.

The Vermacht’s vehicles required specific fuel grades, specialized spare parts, and trained mechanics. Many German units still relied on horsedrawn transport with a single division, requiring thousands of horses that consumed tons of FOD daily. The horses were vulnerable to artillery, required constant care, and limited mobility to walking pace.

Watching American units advance at 30 mph in vehicles that required only gasoline and basic maintenance was deeply demoralizing. By June 15th, German intelligence estimated that American forces in Normandy possessed over 4,000 jeeps with hundreds more arriving daily. This number seemed impossible to officers who remembered the entire German army invading Poland with fewer than 3,000 motor vehicles of all types.

The mathematics of American production suggested that the United States could lose every vehicle in Normandy and replace them all within 2 weeks. Colonel Ernst Vagnner of the Panza Division compiled a report that reached Field Marshall Raml shortly before his injury. We face an enemy who has industrialized warfare to a degree we never imagined possible.

They mass-produce military vehicles with the same methods they produce civilian automobiles. Every American soldier seems to know how to drive and perform basic maintenance. Their entire society is mobilized for mechanical warfare in a way ours never achieved. The disparity in production philosophy proved unbridgegable.

German vehicles like the Cabalva were well engineered, carefully constructed, and designed for longevity. But Germany could produce only a few dozen per day at peak output. American jeeps were simple, crude by German standards, but rolled off assembly lines at rates Germany could not match with all its factories combined. Where German industry sought perfection, American industry sought adequacy multiplied by overwhelming numbers.

General Major Fritz Bioline, commander of the Panza Division, provided a stark assessment. We are fighting the last war while the Americans fight the next one. We perfect individual vehicles while they perfect the system that produces vehicles. We train specialist mechanics while they design vehicles any soldier can maintain.

We are artisans fighting an assembly line and the assembly line is winning. The American systems redundancy frustrated German tactical planning. Destroying a bridge to halt American supply columns proved futile when engineers appeared with portable bridging equipment carried on jeeps. Ambushing reconnaissance patrols achieved little when identical replacement vehicles and crews appeared within hours.

Mining roads only caused Americans to drive through fields. Every German tactical success was negated by American material abundance. The jeep became a symbol of this abundance that transcended its military function. German soldiers reported seeing jeeps used for tasks that would have been unthinkable in the Vermacht. delivering mail, transporting journalists, carrying chaplain to forward positions, even moving generals personal baggage.

This casual use of military equipment for convenience rather than necessity, demonstrated a wealth that German soldiers, accustomed to scarcity and careful preservation, found both amazing and demoralizing. Leitant Friedrich Hoffman wrote to his family, “The Americans use their vehicles like we use bicycles for everything and without concern for wear.

I saw a jeep being used to deliver hot food to a single outpost. A trip that wore the engine and consumed fuel for the comfort of three men. In our army, those men would walk and eat cold rations. This wastefulness should be a weakness, but when you can waste without consequence, it becomes a form of strength. The technological gap appeared in unexpected ways.

American Jeeps came equipped with standardized toolkits, comprehensive maintenance manuals printed on waterproof paper, and spare parts packages calculated by statistical analysis. German vehicles often lacked basic tools, relied on mechanics experience rather than documentation, and competed for scarce spare parts through a complex requisition system that could take weeks.

As June progressed into July, German forces found themselves increasingly unable to compete with American mobility. Static defensive positions were outflanked by jeep-mounted reconnaissance units. Artillery positions were overrun by rapidly advancing motorized infantry. Supply lines were cut by fastmoving patrols that appeared behind German lines, struck and disappeared before reserves could respond.

The battlefield had become fluid in ways that favored the side with unlimited motorized transport. Major Wilhelm Vontobin observing the American breakout preparations in late July wrote, “They have achieved something we thought impossible. The complete motorization of an army. Every soldier can be moved by vehicle. Every gun can be towed at highway speeds.

Every supply item can be delivered directly to the consumer. We’re fighting a 19th century war against a 20th century enemy.” The German high commands attempts to counter American motoriization proved futile. Orders to target vehicle concentrations were meaningless when vehicles were everywhere.

Efforts to interdict supply lines failed when every unit possessed organic transportation. Plans to exploit American dependence on fuel were negated by a supply system that delivered gasoline in quantities Germany hadn’t seen since 1940. By the time of Operation Cobra in late July, American forces in Normandy possessed over 15,000 vehicles with jeeps comprising the single largest category.

The German estimate compiled from prisoner interrogations and aerial reconnaissance suggested the Americans could suffer 50% vehicle losses and remain more motorized than any German division at full strength. This calculation, when reported to Berlin, was dismissed as defic. It was actually conservative. The influence of American motorization extended beyond immediate military impact.

German officers who survived the war would carry these lessons into the reconstruction of postwar Germany. The American model of standardization, mass production, and design simplicity would influence German industrial development. The Volkswagen, which had failed as the Cubalvar to compete with the Jeep in war, would succeed as the Beetle in peace, applying mass production principles the Americans had demonstrated so devastatingly.

Felvable Otto Schultz, who spent 3 years as a prisoner of war in America, later reflected in Normandy. We learned that modern war was not about courage or skill, but about industrial capacity. The Americans showed us that victory belonged to whoever could produce the most ship the fastest and replace losses immediately.

The Jeep was not just a vehicle, but a symbol of a new kind of warfare we were not prepared to fight. The story of German troops encountering American mass motorization in Normandy represents more than a military mismatch. It was a collision between two different civilizations approach to warfare. The Germans, with their tradition of professional military excellence and carefully maintained equipment, met an American military that had transformed warfare into an exercise in industrial management and mass production. In the end, the endless

columns of jeeps that poured across Normandy represented something more profound than military vehicles. They were the physical manifestation of the arsenal of democracy, proof that American industrial might could be projected across oceans and delivered to battlefields in quantities that rendered traditional military calculations obsolete.

For German soldiers watching those columns advance, each jeep was a messenger bearing the same simple truth. The age of artisan warfare had ended, and the age of industrial warfare had begun. The last word belongs to Hedman Erns Bergman, who observed American operations throughout the Normandy campaign and survived to become an automotive engineer in postwar Germany.

The Americans taught us that in modern war, the factory is more important than the battlefield. Their jeeps arriving in endless numbers, each one identical and replaceable, showed us that warfare had become a branch of industry. We thought we were soldiers. They showed us we were simply workers in a factory of destruction.

News

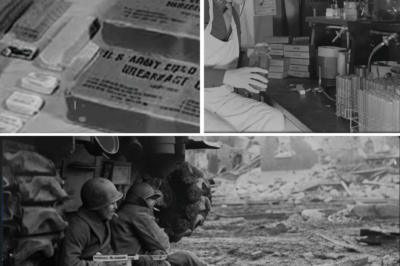

CH1 German POWs Laughed at U.S. Cafeterias — Until They Lined Up for Seconds

The war had ended in Europe, but the prisoners carried their pride with them across the Atlantic. In June 1945,…

CH1 German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted the Army That Never Starved

December 17th, 1944. The frozen earth of the Arden’s forest crunched beneath Vermach boots as German officers surveyed their latest…

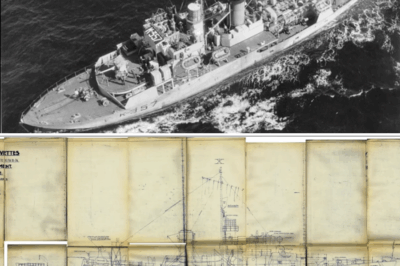

CH1 Why British Corvettes Cost 1/10th of a Destroyer — But Sank More U-Boats

March 1940, Britain’s accountants were calculating how long the nation could survive, and the numbers told a story more frightening…

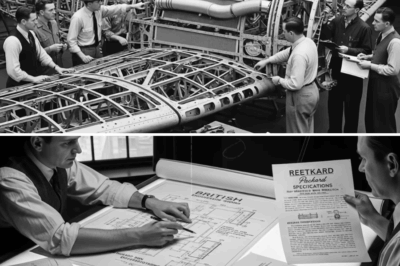

CH1 THE P-51’S SECRET: HOW PACKARD ENGINEERS AMERICANIZED BRITAIN’S MERLIN ENGINE

August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside Packard Motorcar Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant, two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines roared to life…

HOA Called Cops When I Moved Out of the HOA — Lost It When She Learned I Bought the Entire Block

She dialed 911 the moment I packed my first box. “He’s abandoning the rules,” she shrieked into her phone, her…

My Parents Wanted Me To Support My Sister Marrying My Ex-Husband & Took His Side—So I Walked Away..

My parents wanted me to support my sister marrying my ex-husband and took his side. So, I walked away and…

End of content

No more pages to load