In the long dark history of submarine warfare, there is one rule that was never meant to be broken. You do not fight a destroyer. A submarine is a phantom, a ghost in the water. It hunts the slow, lumbering cargo ships and tankers that are the lifeblood of an enemy’s war machine. But the destroyer, the destroyer is the wolf.

It is fast, it is lethal, and it was built for one purpose, to hunt the hunter. In the Second World War, for an American submarine to be caught by a Japanese destroyer was in most cases a death sentence. Between December 1941 and the spring of 1944, Japanese destroyers had successfully sunk 14 American submarines in combat.

In that same period, the number of Japanese destroyers sunk by an American sub while both were actively engaged in a fight was zero. The math was simple. A destroyer could race along at 35 knots. A submerged submarine running on batteries struggled to reach 9. The destroyer had sonar and was loaded with depth charges. The submarine had to hide blind and silent. The doctrine was clear.

If a destroyer finds you, you dive deep. You rig for silent running and you pray. But in 1944, one man decided to rewrite the rules. His name was Commander Samuel De. And he didn’t just fight the wolf, he hunted it. What he and his 79 men did in just 4 days was so unbelievable, it not only shocked the Imperial Japanese Navy to its core, it changed the entire course of the war in the Pacific.

This is the story of the USS Harter, the destroyer killer. To understand what Samuel Dei did, you first have to understand the man himself. He was 37 years old, a 1930 graduate of the Naval Academy. He was quiet, unassuming, and wore spectacles. But beneath that calm exterior was a core of pure steel, forged under the command of the legendary William Mush Morton, the skipper of the USS Wahoo.

De had been Morton’s executive officer, and he learned from the best. He learned that aggression, surprise, and absolute audacity were weapons just as powerful as any torpedo. By 1944, Dei had his own command, the Gateau class submarine USS Harter. On his fifth war patrol, he put those lessons into practice in a way that left the Navy stunned.

On April 13th, 1944, near the island of Guam, the Harter, was hunting a convoy when its escort, the Japanese destroyer Akazuchi, spotted him. The Akazuchi turned and charged at flank speed, intent on ramming or depth charging the submarine into oblivion. Every man in Harter’s conning tower expected the order to dive.

Instead, Dei ordered, “Flank speed ahead. Make ready the bow tubes.” He was charging straight at the destroyer. This was a tactic so reckless it was barely even a theory. It was called the down the throat shot. You fire your torpedoes directly into the face of the charging enemy and then at the last possible second.

You crash dive and pray you get deep enough to pass under his keel. If your torpedoes miss, the destroyer is in the perfect position to drop its depth charges directly on your position. If you dive too late, his bow will slice your submarine in half. At a range of just 900 yardds, point blank range in naval terms. Harder fired a spread of four torpedoes.

Two of them struck the Ikazuchi amid ships. The destroyer erupted in a massive explosion, broke in two, and sank in less than 5 minutes. DIY surfaced, surveyed the wreckage, and sent one of the most famous radio reports of the entire war. It was short, and it was brutally clear. Expended four torpedoes and one destroyer.

This single act of defiance sent a shock wave through the Pacific submarine force, but it also put a target on DE’s back. Admiral Somu Toyota, the commander and chief of the Japanese combined fleet, was not amused. By the spring of 1944, Japan was in a desperate position. Between January and May alone, they had lost 23 destroyers, not just to submarines, but to carrier aircraft and surface battles.

These ships were the irreplaceable sheep dogs of the fleet. The only vessels fast enough to protect Japan’s carriers and battleships from American submarines. Toyota was gathering every ship he had for one last massive gamble. It was called Operation Ago, a plan to lure the American invasion fleet into the Philippine Sea and annihilate it in one Kai Kessan, the decisive battle that Japanese naval doctrine had dreamed of for decades.

To do this, he concentrated the entire Japanese mobile fleet at a remote forward anchorage called Tawi Tawi in the Sulu Archipelago. It was the largest concentration of Japanese naval power since the Battle of Midway. The numbers were staggering. Four battleships, including the super battleship Yamato, nine aircraft carriers, 15 cruisers, and 28 precious destroyers.

They were a coiled spring waiting for the American invasion of the Maranas to begin. But American codereakers at Hypo in Hawaii knew they were there. And Admiral Charles Lockwood, the commander of the Pacific Submarine Force, knew exactly who to send. He sent the one man who wasn’t afraid of destroyers. He sent Samuel Dy harder. His orders were simple.

Get into the Hornet’s Nest, patrol the waters around Tawittowi, and attack any targets of opportunity. For nine agonizing days, Harter operated completely undetected, slipping between Japanese patrols, charting the fleet movements. De was a phantom, just miles from the most heavily guarded anchorage on Earth. Then his luck ran out. At 0300 on June 6th, 1944, the same day Allied troops were storming the beaches in Normandy, a Japanese patrol plane flying in the dark spotted the faint feather of Harter’s Periscope Wake. The alarm was sounded. The hunt was on.

Within an hour, three destroyers, the Minazuki, Hayanami, and Tanekazi, were detached from the fleet with one simple order. Find and kill the American submarine. At 0647, as the first light of dawn streaked the sky, Commander De stood in the conning tower, his eye pressed to the periscope.

He watched as the three destroyers cut through the water, coming right for him. He was 37 years old. This was his fifth war patrol. He had already destroyed 18 enemy ships, but now three of the deadliest ships in the Japanese Navy were hunting him simultaneously. If you find this kind of detail forgotten history as fascinating as we do, we’d be honored if you’d hit that subscribe button.

We believe these stories of courage and sacrifice deserve to be told. And by subscribing, you help us ensure they aren’t forgotten. Back in the Conning tower, DIY studied the lead destroyer, the Minazuki. She was,50 tons of gray steel, armed with four 5-in guns, and closing fast, zigzagging to throw off a torpedo solution.

Behind her, the other two destroyers were spreading out. A classic search and destroy pattern designed to box the submarine into a kill zone. Every man in the harder knew the book. They were supposed to run. They were supposed to dive to 400 ft and pray the sonar operators were having a bad day. But Dei had no intention of running.

He swung Harter’s bow and pointed it directly at the charging Minizuki. Make ready the bow tubes, he ordered. The range closed 1,500 yd, 1,200 yd. The sonar pings from the Minizuki were now a frantic high-pitched clang clang clang that every man in the boat could hear through the hull.

The destroyer knew where they were. Range, 1100 yd, the fire control officer called out. The time to collision was just 96 seconds. Dei was calm. He was waiting for the Minazuki to commit. At 750 yards, less than half a mile, the destroyer was so close De could see the bone in her teeth, the white bow wave she was pushing. Fire one, fire two. Fire three. Three.

Mark 18 electric torpedo sped silently toward the target. Take her down 300 ft. All ahead full. The Harter pitched down at a brutal 30° angle. her motors screaming as she clawed for depth. This was the moment of truth. 40 seconds after firing, two massive explosions shook the harder so violently that light fixtures shattered and cork insulation rained down from the overhead.

Then a third shattering blast lifted the submarine’s stern 6 ft out of the water before slamming it back down, throwing men from their feet. De brought the boat back to Periscope depth where the Minizuki had been. There was nothing but a column of black smoke, debris, and a spreading oil slick. The destroyer had been broken in half. She was gone. But this was no time to celebrate.

The other two destroyers, the Hayanami and Tanakazi, were now racing away, not toward him, but away, dropping depth charges at random in a panic. They clearly believed they had stumbled into a whole wolf pack of American submarines. Not a single audacious attacker. Dadly let them go. He slipped away into the deep. One hunter was dead.

When Admiral Toyota received the news at 0900, he was incensed. He ordered six more destroyers to join the hunt. By noon, the sky over Tawi Tawi was thick with patrol planes, searching every 20 minutes. The entire anchorage was on high alert. Samuel Dy, however, wasn’t finished. In fact, he was just getting started.

He spent the rest of June 6th evading patrols, diving deep when the planes came over. His crew silent, the air in the boat growing thick with the smell of diesel, sweat, and stale coffee. They were being hunted by the most powerful fleet in the Pacific, and their commander was reloading.

Early in the morning of June 7th at 0230, harder surfaced to recharge her batteries. The night was pitch black with no moon and a heavy cloud cover. It was perfect submarine weather. At 0312, the radar operator called out, “Radar contact, single ship, bearing 095, range 8,000 yd, closing fast.” De was on the bridge in an instant.

The contact was moving at 28 knots. There was no question it was another destroyer. This was the Hayanami, one of the two destroyers that had fled the previous day. Her captain, Commander Hideo Kuboki, had been searching for the American sub all night. He was exhausted, and at 0300, he had received orders to return to Tawi. He was heading home.

In the dark, nobody on his bridge expected an American submarine to be waiting for him, let alone to attack him on the surface. De ordered flank speed harder as big diesel engines roared to life, pushing the submarine to 21 knots, a race in the dark. De was deliberately closing the range, trying to get inside the destroyer’s radar detection ring before they could get a clear picture of him.

At 4,000 yd, the Hyanami’s radar operator finally picked up a contact. It was small, moving fast. He likely assumed it was just another Japanese patrol boat returning to base. At 3,000 yd, Commander Kaboki realized his fatal mistake. That wasn’t a patrol boat. It was an American submarine, and it was attacking him.

He ordered flank speed and a hard turn to ram, but it was too late. Deeriscope. Standing on the open bridge, he gave the firing order. Fire one. Fire two. Fire three. Fire four. From 2300 yardds, four torpedoes leaped from the harder. Two of them struck the Hyanami’s starboard side right near the aft magazine. The resulting explosion was catastrophic.

The entire stern of the destroyer was torn completely off. The ship rolled over 90°, her propellers still spinning uselessly in the air, and she sank stern first. Commander Kuboki and 147 of his sailors went with her. Di gave the order. Crash dive. He knew that patrol planes would be overhead within minutes.

He had just sunk two Japanese destroyers in less than 24 hours right on the doorstep of their main fleet anchorage. The Imperial Japanese Navy wasn’t just hunting him anymore. This was personal. Admiral Toyota was furious. He was now facing a crisis. Two destroyers gone, sunk by the same submarine. This was not just a nuisance.

It was a profound humiliation and a critical loss of his anti-submarine screen. He immediately pulled eight more destroyers from convoy escort duty, ships that were desperately needed to protect his tankers and transports and organized them into dedicated hunter killer groups. Their only mission, find and destroy the American submarine at Tawi Tawi.

Every Japanese destroyer captain in the area received the same orders. Maximum aggression, no retreat. Kill that submarine. Samuel Dy knew the Hornet’s nest was well and truly stirred. A sane commander would have taken his two victories and left the area at high speed. But De was not a sane commander. He was a hunter. On June 8th, he took harder south toward the Sabutu passage.

This was the narrow deep water straight between Tawittowi and Borneo. It was the main shipping lane and Dei knew the Japanese destroyers would be patrolling it heavily. He wanted to see just how many he could sink before they finally figured out what he was doing. At 1,400 hours, the lookout spotted them. Smoke on the horizon. two ships.

It was the Tanakazi, the third destroyer from the original hunting party, along with an unidentified escort. They were steaming in formation at 25 knots, sweeping the passage. Dei submerged and began his approach. For 90 long minutes, he just watched. He studied their movements. He saw they were following a predictable zigzag pattern, changing course every 8 minutes. This was sloppy.

It gave him a window maybe 30 seconds after each turn to set up and fire. So he positioned harder directly in their path, raised his periscope and waited. At 16:30, right on schedule, the Tanakazi turned toward Harter’s position. Range 3,000 yd, Dei said, his voice calm. He let her come. 2500 yd, 2,000,500. The Tanakazi was so close her bow filled the periscope’s view. At 12,200 yd, De gave the order.

Fire one, fire two, fire three, fire four. He fired a wide spread with 17-second intervals between each torpedo to make sure one of them hit. The first torpedo missed, running just ahead of the bow, but the second struck the Tanakazi right near the bridge. The third torpedo hit just seconds later, detonating the forward magazine.

The explosion was so massive that the crew inside harder deep underwater heard it clearly. A deep crunching hump that vibrated through their bones. The Tanakazi’s entire bow section was separated from the main hull and both pieces sank in less than 3 minutes.

The escort destroyer, seeing its partner disappear in a ball of fire, went berserk. It immediately turned and charged Harter’s position, dropping depth charges as it came. “Take her deep, 400 ft,” Dei commanded. The depth charges exploded overhead, shaking the submarine violently, but they were dropped in panic, not with precision. They caused no serious damage.

After 40 minutes of this, the lone destroyer, likely fearing it was next, gave up the hunt and withdrew to rescue survivors. Three destroyers, three days. The news hit Admiral Toyota’s flagship like a physical blow. The devil of Tawiti, as the Japanese were now calling this lone submarine, had struck again.

Toyota was about to make a decision that would change the entire course of the Battle of the Philippine Sea. But first, Samuel Dei had one more destroyer to sink, and this time he was going to do it in broad daylight with two other Japanese destroyers watching. On June 9th at 0500, De brought harder to periscope depth just 12 mi southwest of the Tawittowi anchorage.

What he saw made every man in the conning tower hold his breath. Dead ahead, steaming in a perfect line of breast formation, were four Japanese destroyers. They weren’t transiting. They were actively hunting. Their sonar was pinging so loudly that Harter’s sound operator could hear it clearly without his headphones.

This was the hunter killer group sent specifically for him. De checked his torpedo status. He had eight torpedoes remaining, four destroyers. This meant he would get maybe one shot before all four of them converged on his position and buried him under an avalanche of depth charges. He studied their formation. The lead destroyer on the end was zigzagging aggressively.

The third and fourth destroyers were also moving erratically, but the second destroyer in the line, for some reason, she was maintaining a steady course. That was his target. At 0612, the second destroyer turned directly toward Harter’s position. It was a routine turn in her search pattern, but it sealed her fate. Range 4,000 yd. De waited.

3,000 yd. The sonar pings were deafening. 2500 yd. At 1,800 yd, De spoke. Fire one. Fire two. Fire three. He didn’t fire his usual spread of four. He needed to save his torpedoes. He was betting everything on this one shot. All three torpedoes struck the destroyer’s port side within 5 seconds of each other.

The ship didn’t just explode. It disintegrated. The blast was so violent that debris, chunks of the deck, guns, pieces of the superructure flew 300 ft into the air. The ship rolled over and was gone in 90 seconds. The other three destroyers witnessing this reacted with absolute fury. They immediately converged on Harter’s last known position. Emergency deep. 500 ft. De roared.

The Harter nosed over and plunged. Depth charges began exploding overhead almost immediately. 23 of them in the first 10 minutes. The explosions were bonejarring. The lights in the submarine went out and the dim red emergency lighting kicked in. The hull plates groaned and popped under the immense pressure.

A sound the crewman called the bends. A pipe burst in the forward torpedo room, spraying high pressure seawater across the deck. But the crew was silent. They were veterans. They moved in the dark, repairing the damage, while the world outside their thin steel hull was nothing but thunder. For two solid hours, the three destroyers hunted them.

They crisscrossed the spot, dropping charge after charge. But Dei was just as good at evasion as he was at attacking. He kept harder, deep, and silent, anticipating their moves until finally the destroyers gave up. They likely assumed the submarine had been destroyed by the sheer volume of their attack.

At periscope depth, the sea was empty. Four destroyers sunk in just 4 days. De wasn’t thinking about his success. He was thinking about his fuel gauges. harder had burned through 60% of her diesel reserves. She had five torpedoes left, but she could only stay on station for maybe three more days. While DI was checking his fuel, the report of the fourth sinking reached Admiral Jizaburo Ozawa, the commander of the mobile fleet, who was still at Tawi Tawi. Ozawa did the math.

Four destroyers sunk in 4 days by one submarine. right outside his main fleet anchorage. If a single American submarine could penetrate his defensive screen this easily and sink his best escorts at will, the entire anchorage was a death trap. All his carriers, all his battleships were just sitting ducks. He sent an urgent panicked message to Admiral Toyota.

The mobile fleet must depart Tawittowi immediately. The Americans knew where they were. Toyota agreed. The original plan for Operation Ago was to wait until the Americans committed to their invasion and then sail on June 15th to intercept them. But staying at Tawitawi was no longer an option. It was suicide. On June 10th at 0800, the entire Japanese mobile fleet, four battleships, nine carriers, 15 cruisers, and the remaining 24 destroyers weighed anchor and steam northeast 6 days early heading for the Philippine Sea. Their departure was a mess. They were disorganized and they

were leaving in a hurry. American codereakers intercepted their movement orders within hours. Admiral Raymond Spruent, commander of the American Fifth Fleet, now knew exactly where Ozawa was going, and he had an extra 6 days to prepare his reception. Daly, of course, knew none of this. He was still hunting.

Later that same day, June 10th, at 16:30, he spotted two more destroyers patrolling the Sabutu Passage. He had five torpedoes left, enough for one more attack. At 1715, he fired a spread of three torpedoes at the lead destroyer. One struck the bow. The destroyer was heavily damaged and slowed to a stop, but it didn’t sink. The second destroyer, seeing its companion hit, instantly charged Harter’s position.

Deired his last two torpedoes. Fire four. Fire five. Both of them missed. The conning tower was silent. They were out of torpedoes. They had no way to defend themselves. And a Japanese destroyer was bearing down on them at 32 knots, less than a mile away. Its bow wave a white line of pure vengeance. Emergency deep. Take her down. 500 ft.

Harter’s diving planes bit hard, pushing the submarine down at a maximum angle. The men grabbed for handholds. 300 ft. 400 ft. 500 ft. The destroyer passed directly overhead. Its propellers churned the water so loudly that the crew could hear the wump wump wump of the individual blades through the hull. Then silence.

The destroyer was circling back. Dei knew the pattern. The destroyer would make multiple passes, dropping depth charges on each run until the submarine either surfaced or imploded. Harder had no torpedoes to fight back. Her only option was to endure the storm and hope the destroyer ran out of depth charges first. The first pattern of six depth charges dropped at 1723.

They exploded in a tight, perfect pattern right around the submarine. Harder, rolled 15° to starboard. Light bulbs shattered. Men were thrown against the bulkheads. A second pattern dropped 2 minutes later, even closer. The explosions lifted the submarine’s stern and slammed it back down. A hydraulic line burst in the control room, spraying a fine mist of oil.

For 90 minutes, the destroyer hunted them. 42 depth charges. Most exploded too shallow or too deep, but three came close enough to crack gauge glasses and spring minor leaks. De kept harder at 500 ft, moving at a dead slow two knots, making as little noise as possible. Finally, at 1900 hours, the destroyer withdrew.

She had exhausted her depth charge supply. De waited another hour in the crushing silence before surfacing. The ocean was empty. Harter was battered, but alive. She was out of torpedoes and low on fuel. The patrol was over. She limped south toward Fremantle, Australia. Arriving on June 26th, the moment Harter tied up at the pier, Admiral Lockwood was waiting for him. He had been tracking De’s reports.

Five destroyers attacked, four confirmed sunk, one heavily damaged. In 12 days, it was and still is the most successful anti-destroyer patrol in the history of naval warfare. Lockwood awarded Dei the Navy Cross right there on the deck. Then he asked the question every submarine commander dreaded after a grueling patrol. Can you do it again? De’s answer was immediate.

Give me torpedoes and I’ll sink 10. The Harter’s crew spent July in free metal repairing the sub and resupplying. Dei, now a legend in the force, trained new crew members on his down the throat tactic. By late July, every submarine commander in the Pacific had studied his patrol reports. The tactic worked.

Between June and August, American subs emboldened by De’s success, sank 14 more Japanese destroyers using variations of his aggressive approach. The hunters had become the hunted, but the full impact of Harter’s patrol was only just being understood. The battle of the Philippine Sea began on June 19th, just 9 days after Dei sank his fourth destroyer.

Because Admiral Ozawa’s fleet had been forced to leave Tawitawi 6 days early, his entire battle plan collapsed. His fleet arrived scattered and disorganized. His reconnaissance planes had burned through their fuel reserves during the hasty departure and couldn’t find the American fleet. His destroyers were still regrouping.

His supply ships were 3 days behind schedule. When American carrier aircraft found Ozawa’s fleet, the Japanese were completely unprepared. The result was a slaughter. American pilots facing disorganized and undermanned Japanese air patrols shot down 376 Japanese aircraft while losing only 30 of their own.

They called it the Great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot. American submarines, including the Cavala and Albakor, sank two of Ozawa’s largest carriers, the Shokaku and Taiho. American planes sank a third, the HEO. The Imperial Japanese Navy lost 75% of its carrier air groups in two days. It was a blow from which they would never recover.

And it all happened because one submarine commander Samuel Dy was aggressive enough to sink four destroyers in four days, convincing the Japanese that their fortress at Tawittowi was a death trap. Admiral Lockwood in his post-war memoir called Harter’s Fifth Patrol the single most strategically important submarine operation of the entire Pacific War.

On August 5th, 1944, Harter departed Fremantle for her sixth war patrol. She was assigned to a three submarine Wolfpack with the USS Hado and USS Hake De as the senior skipper was in command. Their mission was to patrol the waters west of Luzon in the Philippines and destroy Japanese shipping. The patrol started with incredible success.

On August 21st, the Wolfpack sank four large cargo ships. On August 22nd, Harter and Hado attacked a group of coastal defense vessels, sinking three of them. Harter was credited with two, the frigots Matsua and Hibburi. By August 23rd, Hado had expended all her torpedoes and withdrew. This left Harder and Huck operating together off Dassel Bay. But the Japanese were learning.

Their intelligence had tracked the Wolfpack’s movements. They knew where the American submarines were. And this time, they had sent something special to deal with them. At 0453 on August the 24th, the USS Hake was submerged 4 miles off the coast. Through her periscope, her captain could see harder on the surface 45,500 yards to the south. They were coordinating an attack on a Japanese ship.

Suddenly, Hakes sonar operator heard the one sound that made his blood run cold. Echo ranging. Close. Getting closer. Two Japanese escort ships CD22 and Mind Sweeper PB102 were closing fast on Harter’s position at 18 knots. They were actively hunting. Japanese intelligence had intercepted the radio transmissions between the Wolfpack and knew they were in the area.

Hank’s captain immediately ordered his submarine deep and silent. He watched through his periscope as the two Japanese ships closed on Harter. His radio operator frantically tried to warn De, but there was no response. At 0530, Harter finally saw them. She crash dived, but it was too late. The Japanese ships were less than 2,000 yd away.

Dele took harder down fast at a 35 degree angle, but in his haste, his diesel engines were still running as he submerged, leaving a massive trail of bubbles on the surface. A perfect target. The sonar operator on CD22 had a perfect contact, range, 1200 yd, depth 200 ft, and still diving. At 0547, CD22 made her first pass and dropped a full pattern of depth charges, all set to detonate at 250 ft. The explosions bracketed harder perfectly.

At least three detonated within 50 ft of her hull. The pressure hull of the Harter cracked near the after torpedo room. Seawater flooded in at a tremendous pressure. The stern compartments flooded completely in 90 seconds. The submarine’s bow rose sharply as the stern dragged her down. In the control room, De would have been roaring blow all ballast emergency surface, but the compressed air system fighting against the weight of thousands of tons of flooding water couldn’t save her.

At 0552, CD22 made a second pass. This pattern hit even closer. The explosions ruptured. Harter’s main pressure hull in multiple locations. The control room flooded. All electrical power failed. At 600 ft, well below her maximum operating depth. Harder’s hull began to implode. The bulkheads collapsed. The compartments were crushed like tin cans.

At 0600, the Japanese ships reported a successful kill. Large quantities of oil, wood debris, and cork floated to the surface. They circled for 2 hours, dropping more charges to be certain. They recovered no survivors. All 79 men aboard the Harter were gone. Commander Samuel Dei, the destroyer killer, had been killed by the very escorts he had taught the Navy how to destroy.

The news of Harter’s loss was a devastating blow to the submarine force. Admiral Lockwood immediately suspended all submarine operations in the area. The American public wouldn’t learn the full story until after the war, but the Japanese knew. Admiral Toyota received the report on August 26th. The devil of Tawittowi was finally gone. He ordered a commendation for the crew of CD22.

What Toyota didn’t know was that the damage was already done. The tactics De had pioneered were now standard doctrine. Before Harter’s fifth patrol, submarines ran from destroyers after they hunted them. By the end of the war, American submarines using De’s down the throat tactic had sunk 214 Japanese warships.

This included four aircraft carriers, one battleship, nine cruisers, and 38 destroyers. Dele’s legacy was written in the wreckage of the Imperial Japanese Navy. On March 27th, 1946, President Harry Truman presented Commander Dele’s Medal of Honor to his widow, Edwina, on the White House lawn. The citation read in part, “This remarkable record of five vital Japanese destroyers sunk in five short-range torpedo attacks attests the valiant fighting spirit of commander Dei and his indomitable command.

” The Navy named a destroyer escort after him, Harter. Herself received the presidential unit citation. Her motto, hit him harder, became legendary. Today at the Naval Academy, instructors still teach the down the throat attack. Not because modern submarines would use it, our new torpedoes are far too advanced for that, but because it demonstrates a fundamental principle.

When your enemy expects you to run, charging is the one thing they can’t defend against. The 79 men aboard Harter came from 38 different states. They were farm boys from Iowa, factory workers from Michigan, college graduates from California. They volunteered for the silent service, knowing the odds. 22% of all submariners who served in World War II died. The highest casualty rate of any branch of the American military.

They knew the risk and they served anyway. The last survivor of Harter’s crew, Paul Bryce, passed away in 2022 at the age of 98. With his death, no one who served aboard that legendary boat remains to tell their story firsthand. That is why these stories matter. The official reports tell us what they did. But they can’t tell us what it felt like to hear those depth charges explode or to trust your life to the man at the periscope. If this story moved you, please hit that like button.

Every click tells the algorithm that this piece of history is worth remembering and it shows this story to more people. We’re dedicated to rescuing these forgotten stories of real heroism from the archives. If you want to join us on this mission, please subscribe and turn on notifications. And finally, we have one question we always ask.

Where are you watching from? Our community stretches across the entire globe. From the United States to the United Kingdom, from Canada to Australia. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of a community keeping these memories alive. Please drop a comment and let us know your city or state and tell us if someone in your family served.

Thank you for watching and thank you for ensuring that Commander Samuel Dy and the 79 men of the USS Harter do not disappear into silence. They deserve to be remembered.

News

“Where do you think you’re going?! Your guests have arrived!” the mother-in-law exclaimed—only to get exactly the answer she deserved.

Anna carefully parted the curtain and looked out the window. The familiar white Logan pulled up to the gate, and…

The husband left for a younger woman, leaving his wife with enormous debts. A year later, he saw her behind the wheel of a car that cost as much as his entire company.

“I’d leave you the keys, but there’s no point.” Elena slowly raised her head. Andrey was standing in the doorway,…

CH1 THE ENTIRE World War II From The German Perspective | Documentary in PURE COLOR

When Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Germany was still bound by the impositions of the Treaty of…

CH1 Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

four hundred planes vanished 400 aircraft launched into the Pacific sky only a handful returned what happened on June 19th,…

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

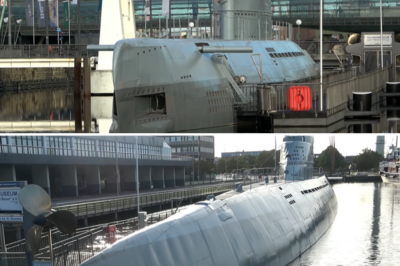

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

End of content

No more pages to load