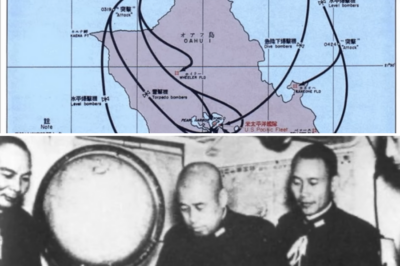

August 6th, 1943, 11:30 p.m. Velf, Solomon Islands. Commander Kaju Sugura stood on the bridge of the destroyer Shigur, scanning the darkness ahead. The sea was calm, no moon, perfect conditions for what the Japanese Navy did best. Night fighting. Behind Shigur, three more destroyers cut through the black water in perfect formation.

Hagaz, Arashi, Kawakaz. four warships carrying 900 troops and supplies to reinforce Japanese positions at Colombangara Island. This was the Tokyo Express, the Rat Run. For 18 months, Japanese destroyers had owned these waters after dark. American ships feared the night. Japanese crews mastered it. Sugiura had run this mission 14 times.

14 times he delivered troops, engaged enemy ships, and returned to base. The Americans called it the Tokyo Express because it ran on schedule and nothing could stop it. Tonight would be different. In August 1942, American forces landed on Guadal Canal. The island became the pivot point of the Pacific campaign. Whoever controlled the Guadal Canal controlled the Solomon Islands.

Whoever controlled the Solomons controlled the sea lanes to Australia. The Japanese needed to reinforce their garrison, but American aircraft controlled the daylight hours. Any Japanese ship caught in the slot during the day would be bombed into scrap metal. So the Japanese Navy developed a solution. High-speed destroyers run under cover of darkness.

Load troops and supplies at dusk. Race down the slot at 30 knots. Unload before dawn. Return to base before American planes could find them. They called it the rat run. The Japanese called it the Tokyo Express. And for 18 months it worked. The reason was simple. Japanese crews were the best night fighters in the world.

Every officer spent two years training in optical night combat. They could spot enemy ships at 12 km in total darkness. American lookouts could barely see 8 km. Japanese destroyers carried the Type 93 torpedo, the Long Lance. Oxygenfueled, wakeless with a 20 km range. American torpedoes left visible trails and ran half the distance. Japanese tactics were refined through hundreds of night engagements, coordinated turns, synchronized torpedo spreads, and radio silence.

They fought like a pack of wolves in the dark. The statistics told the story. In 1942, Japanese destroyers won 80% of night engagements in the Solomons. They sank two American cruisers at Tsavo Island without losing a single ship. They delivered 30,000 troops to Guadal Canal despite American air superiority. By August 1943, the Tokyo Express had run over 60 missions.

The Japanese Navy believed the night belonged to them. Commander Sugura believed it, too. Kaju Sugura was 34 years old. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1931, ranked seventh in his class. He’d served on destroyers for 12 years. He fought at the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942. He participated in the bombardment of Henderson Field on Guadal Canal.

He’d run the Tokyo Express 14 times without losing a ship. His first Tokyo Express mission came in October 1942. Sugura commanded Shigur through Iron Bottom Sound at midnight, evading American cruisers through precise navigation and radio silence. He delivered 240 troops to Guadal Canal and returned to Rabul before dawn.

Zero casualties. Mission success. By August 1943, Sugura had perfected the art. He knew every reef in the slot. He could identify American destroyer silhouettes at maximum visual range. His crew executed evasive maneuvers without verbal orders. Hand signals and practiced coordination were enough. Sugura was an expert in night combat.

He could identify ship silhouettes at extreme range. He could calculate firing solutions in his head while maneuvering at full speed. He trained his crew to execute complex tactical maneuvers in complete darkness without radio communication. His confidence wasn’t arrogance. It was an experience. 14 missions, 14 successes.

The Americans had tried to stop the Tokyo Express dozens of times. They’d failed. On the night of August 6th, Sugura commanded a four ship formation. His orders were straightforward. Deliver 900 troops and 40 tons of supplies to Colombangara. Engage any enemy forces encountered. Return to base before dawn. Standard mission routine operation.

Sujiraa stood on Shigar’s bridge as the four destroyers entered the Gulf at 11:30 p.m. The night was moonless. Visibility was less than 2 km. perfect conditions. He raised his binoculars and scanned the darkness ahead. He saw nothing. That was normal. In night combat, you rarely saw the enemy until you were within 8 km, some

times closer. 11:43 p.m. Shigur’s primitive radar warning receiver crackled. It detected radio waves, but couldn’t determine direction or distance. Just a vague alert. Something out there was transmitting. Sugura ignored it. Japanese radar technology was years behind American development. The warning system gave false alerts constantly.

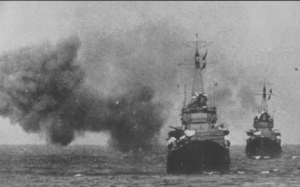

It was useless for tactical decisions. He relied on his eyes, his binoculars, his experience. 11:46 p.m. A massive explosion lit up the sea 300 m to starboard. Hagazi, the lead destroyer, erupted in flames. Her forward magazine detonated. The ship broke in half. Sugura spun toward the explosion, binoculars raised. He scanned the darkness beyond Hajikazi’s burning wreck. Nothing.

No enemy ships, no muzzle flashes, no torpedo wakes. 11:51 p.m. Arashi, 500 m ahead, took three torpedo hits in rapid succession. The destroyer rolled onto her side and sank in 4 minutes. Sujura ordered his crew to fire star shells. Illumination rounds raked into the sky and burst above the sea, casting harsh white light across the water. The ocean was empty.

No American ships were visible, but the torpedoes had come from somewhere. Sugura ordered Shigur to turn hard to port, increasing speed to 32 knots. Evasive maneuvers, break contact. Survive. 11:58 p.m. Kawakas attempting to rescue survivors from Arashi took two torpedo hits amid ships. She went down in 6 minutes.

Three ships were gone in 15 minutes. Sujura never saw the enemy, not once. His lookouts, trained for 2 years in night optical combat, saw nothing. His binoculars, the best in the Imperial Navy, revealed an empty ocean. Shigur fled south at maximum speed, zigzagging desperately. Sugara expected torpedoes to strike his ship at any moment.

They never came. At 12:30 a.m., Shigura cleared Veligulf and reached open water. Sugura reduced speed and took stock. Three destroyers sunk. 1,200 men dead or missing. The mission failed. Supplies lost. And he had no idea what had killed them. Sugjura’s report to naval headquarters was brief and terrifying.

Engaged enemy force of unknown size. Lost three ships in 90 minutes. No visual contact with the enemy was achieved. Cause of attack unknown. Japanese intelligence officers debriefed Sugura for 6 hours. They showed him reconnaissance reports, radio intercepts, technical assessments. The Americans had deployed a new weapon, the SG surface search radar.

It wasn’t new technology. The British had used radar since 1940, but the SG radar represented a breakthrough in miniaturization and accuracy. It could be installed on destroyers. It could detect ships at 20 km and it could guide torpedo attacks in total darkness. The SG radar operated at 10 cm wavelength using a magnetron-based transmitter that Japan’s electronics industry couldn’t replicate.

The system weighed 1,500 lb, compact enough for destroyer installation. It provided continuous 360° coverage with a rotating antenna refreshing every 12 seconds. American radar operators received contact reports on a cathode ray tube display. Range accuracy within 50 m. Bearing accuracy within one degree. The system could track multiple targets simultaneously, calculating speed and heading automatically.

Japanese destroyers carried type 21 radar warning receivers, primitive devices that could only detect radar emissions, not determine range or bearing. The equipment was unreliable, generating false alerts constantly. Most Japanese commanders ignored the warnings entirely. The American destroyers at Veligulf had tracked Sugura’s formation for 25 minutes before opening fire.

They’d calculated his speed, heading, and formation spacing. They’d maneuvered into a perfect firing position. They’d launched 18 torpedoes with radar guided accuracy, all without Sugura seeing them once. The technical specifications were devastating. SG radar detection range 20 km, accuracy within 50 m, refresh rate every 12 seconds.

Japanese optical lookouts detection range 8 to 12 km depending on visibility and crew training. The Americans could see Japanese ships at 20 km in pitch darkness. The Japanese couldn’t see American ships at 8 km in perfect conditions. The gap wasn’t tactical. It was technological and it was insurmountable. Japanese destroyers carried primitive radar warning receivers but no search radar.

Japan’s electronics industry couldn’t manufacture the components. The magnetrons required for centimetric radar were beyond Japanese production capability. Even if Japan could build SG equivalent radar, they couldn’t produce it in quantity. American factories were installing SG radar on destroyers at a rate of 12 ships per month.

Japan’s entire electronics industry couldn’t match that output. Sujura understood the implications immediately. 18 months of tactical superiority erased. 2 years of night combat training obsolete. The Tokyo Express finished. The Americans hadn’t built a better ship. They’d built a better way to sea. And in naval warfare, the side that sees first wins.

Vel was the turning point. Before August 6th, 1943, Japanese destroyers won 80% of night engagements in the Solomons. After Vela Gulf, that number dropped to 15%. The Americans had cracked the code. Radar guided night fighting became standard doctrine. Every destroyer task force in the Pacific received SG radar and tactical training.

3 months later, the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay confirmed the pattern. Japanese cruisers and destroyers engaged an American task force at night. The Americans detected the Japanese formation at 18 km. They maneuvered into firing position while the Japanese were still searching visually. Result: One Japanese cruiser sunk. Three destroyers were heavily damaged.

American losses, minor damage to one destroyer. The Tokyo Express stopped running. Japanese garrisons in the Solomons were cut off from resupply. Guadal Canal’s supply line collapsed. By November 1943, Japan had evacuated the entire Solomon Islands chain. The strategic consequences were catastrophic.

Without the Tokyo Express, Japan couldn’t reinforce forward positions. Without reinforcement, those positions fell. The American advance through the Pacific accelerated, but the tactical consequences were worse. Japanese destroyer crews, the elite of the Imperial Navy, lost confidence. They’d trained for years to master night combat. That training was now worthless.

They were fighting blind against an enemy that could see perfectly. Commander Sugura survived the war. In 1952, he was interviewed by American naval historians researching Pacific war tactics. His assessment was blunt. We were not inferior as sailors. We were not inferior in courage or training. We were simply blind.

You cannot win a fight you cannot see. At Veligulf, we fought ghosts. We died without ever seeing what killed us. That is not combat. The battle of Gulf revealed a fundamental truth about World War II. Industrial capacity was a weapon more powerful than any gun or torpedo. Consider the mathematics of the technology gap.

Training a Japanese destroyer crew for elite night combat. 2 years per crew, intensive optical training, hundreds of hours at sea, limited by instructor availability and ship availability. Installing SG radar on an American destroyer. Two weeks in port, standard equipment. Minimal crew training required.

Limited only by production capacity. American shipyards were installing SG radar on 12 destroyers per month. By late 1943, Japan’s entire electronics industry couldn’t produce 12 radar sets per year. The gap wasn’t just technological, it was industrial, and industrial gaps cannot be closed through courage or tactical innovation.

Japanese destroyer captains were among the finest naval officers in the world. Their crews were superbly trained. Their tactics were proven through dozens of successful engagements. None of it mattered. American radar operators were often 19-year-old recruits with 6 weeks of training. They didn’t need to identify ship silhouettes or calculate firing solutions mentally.

The radar did it for them. The technology turned average sailors into effective combatants. This was the pattern across every theater of World War II. German tank crews were better trained than American crews, but American tanks were produced in overwhelming numbers. Japanese pilots were more experienced than American pilots, but American aircraft had better radios, better gun sights, better engines.

Superior training could not overcome superior production. At Gulf, Commander Sugura commanded a crew that represented years of investment in training and experience. The American destroyers that destroyed his formation were crewed by men who’d been civilians 18 months earlier. The Americans won because their industry could produce radar faster than Japan could train elite sailors.

Postwar analysis by both American and Japanese naval historians reached the same conclusion. Vela Gulf marked the end of Japanese tactical superiority in the Pacific. After August 1943, American technological advantages, radar, radio communications, damage control systems, and logistics made Japanese tactical skill irrelevant.

Sujura’s final assessment was recorded in 1952. We fought the war we trained for. The Americans fought the war their factories built. In modern combat, factories matter more than training. We learned that lesson at Vela Gulf. We paid for it with 1,200 lives in 90 minutes. The invisible technology that sank three destroyers at Velf wasn’t just radar.

It was the industrial system that could produce radar in quantity, install it fleetwide, and integrate it into doctrine within months. Japan couldn’t match that. No amount of courage or skill could close that gap. August 6th, 1943. Vela Gulf. Three Japanese destroyers sank in 90 minutes. Zero American ships were damaged.

The Battle of Veligulf was not the largest naval engagement of World War II. It was not the most decisive, but it revealed a truth that defined the Pacific War. Technology is a force multiplier that makes traditional tactical advantages obsolete. Japanese destroyer crews were the best night fighters in the world. American radar made that expertise irrelevant.

The Tokyo Express ran for 18 months because Japanese sailors could see better in the dark than American sailors. SG radar gave Americans the ability to see perfectly in total darkness. The lesson applies beyond 1943. In modern warfare, information dominance decides battles before the first shot is fired. The side that sees first shoots first. The side that shoots first wins.

Commander Sugura survived Veligulf. Shigur survived the war. One of only 10 Japanese destroyers to do so. Sugura never commanded another Tokyo Express mission. There were no more missions to command. The invisible technology that destroyed three ships in 90 minutes changed naval warfare forever. Not through firepower, through information.

At Veligul, the Americans didn’t outfight the Japanese. They outsaw them. And in war, that’s all that matters.

News

CH1 German U Boat Commander Had 36 Hours to Beat US HF/DF – Lost 6 Boats in One Week

North Atlantic spring 1943. Corvette and Captain Hansom Schwank, commander of U43, breaks radio silence to report a convoy. Convoy…

CH1 The Secret German Fighter That Could Have Won WWII

Hotbus, Germany. January 1945. Kurt Tank stood beside his latest creation as the ground crew completed final preparations. The TAR…

CH1 Admiral Genda Shocked When He Realized The War Was Lost In Just 6 Months

September 1941, Major General Minoru Jenda stood before the Imperial Japanese Navy’s war council with absolute confidence. The plan was…

CH1 German Engineer Watched Americans Build 60-Meter Bridge in 8 Hours

March 1945, East Bank of the Rine, Germany. Hedman Klaus Bergman peers through his binoculars. On the opposite bank, American…

CH1 The “Das Boot” U-Boat Commander Hunted by Allied Radar – 43 Subs Lost in One Month

May 1943 breast France Capitan Zor Hinrich Layman Villinbrock stood at the window of his office overlooking the submarine pens…

CH1 “Hollywood Star Speaks Out: Why Amanda Seyfried’s Bold Stand Has Everyone Talking”

In a world where public figures often walk on eggshells, carefully weighing every word before it escapes their lips, it’s…

End of content

No more pages to load