She was a monster of steel, the largest aircraft carrier ever built. So secret that even most of Japan’s navy had never seen her. The Shinano was designed to turn the tide of war, a floating fortress meant to restore Japan’s crumbling empire. Yet just ten days after leaving port, she was gone. Sunk in the darkness by a single American submarine, becoming the largest warship ever lost to a sub.

The clash between giant and Hunter that left one haunting question how could the pride of Japan vanish so quickly? By late 1944, the Pacific War was reaching its peak. Japan’s once dominant navy was crumbling under the weight of relentless American attacks. The crushing defeat at midway in 1942 had shattered the Empire’s striking power, with four of its frontline carriers gone in a single blow in a last ditch effort.

The Japanese navy rushed a massive secret weapon into service. The Shinano of the largest aircraft carrier ever built. At that time, originally laid down as a Yamato class super battleship, the unfinished hull was converted into a floating air base, stretching three football fields long and weighing 71,000 metric tons.

Her top speed was 27 knots, or 31mph, with a range of 10,000 nautical miles, and she could carry over 160 aircraft. The design included large anti torpedo bulges below the waterline, but to speed up construction. Her planned 16 inch armor belt was reduced to just six inches, leaving her critically vulnerable. Below her deck.

On November 19th, 1944, the Yokosuka Naval Shipyard buzzed with music, flags, and cheers as the Shinano was officially commissioned. But the celebration was cut short when an American B-29 reconnaissance plane was spotted overhead, snapping this rare photo of the massive ship. The timing sent shockwaves across Tokyo.

Fearing an imminent air attack, High Command issued a desperate order. Standing at her helm was Captain Toshio Abe, a quiet but capable officer now burdened with saving Japan’s empire. His task was to immediately sail Shinano 300 miles south to the fortified naval base in Kure, ready or not to continue outfitting.

Captain Abe protested. The ship wasn’t ready. Watertight doors were missing. Bulkhead openings for cables were unsealed, and, most critically, her fire mains and bilge systems were inoperable. But for Japan’s battered navy, the ship was a symbol of renewed hope. And her journey was now a race against time. But fate had other plans.

Lurking silently beneath the waves was the American submarine USS Archerfish, commanded by Captain Joseph Enright. But Enright had failed before, time and again. Enemy ships had slipped through his sights. He vowed this time would be different. At 5 p.m. on November 28th, she slipped from the docks, escorted by three experienced destroyers.

Isokase, Yukikaze and Hamakaze on board were 2000 officers and crew, along with 300 shipyard workers and 40 civilian contractors, still welding, wiring and racing to finish the ship as she sailed. Abe preferred a daylight passage since it would give him extra time to train his young crew. However, he was forced to make a nighttime run when he learned the Navy General Staff could not provide air support.

Below deck, Shinano carried a deadly cargo, six Shinyo suicide boats, and 50 rocket powered Ohka Kamikaze planes. Captain Abe pressed on at a reduced speed of just 20 knots. Four of Shinano’s 12 boilers were offline, leaving her with only partial engine power. Still, the trip to Kure was expected to take only 16 hours.

As the flotilla cleared Tokyo Bay. The ships began zigzagging, a standard tactic to evade submarine attacks, roaming the waters to the south. The USS Archer fish surfaced just after dusk. Captain Joseph Enright, a native of North Dakota, was on his first war patrol aboard his new vessel just a year before he had personally stepped down from command.

Doubting his own judgment after failing to intercept the Japanese carrier Shikaku, now with a seasoned crew and a second chance, Enright was determined to redeem himself. At 8:50 p.m. on November 28th, under a full moon, the crew of the Archer fish detected something big radar blips 14 miles away to the northeast from the submarine’s deck.

Captain Enright scanned the horizon through binoculars. At first, he thought it was an oil tanker with escorts, but as the shape grew clearer, reality set in. This was no tanker. It was a giant aircraft carrier, the likes of which they’d never seen. Breaking protocol. And Wright ordered continuous radar pings to track the target.

Knowing full well it would alert the enemy to their position. He set a course to shadow the carrier to keep pace. The submarine would have to stay on the surface. Being submerged was far too slow for the chase. Then a sense of doubt crept over the captain. What could one submarine do against such a massive ship? Just a month earlier, it had taken 19 torpedoes and countless bombs to sink her sister ship, Musashi.

Meanwhile, aboard the ship Shinano, the radar pulses were immediately detected. Captain Abe took note, but remained calm. One submarine harmless. Only a coordinated strike from a wolf pack of submarines could threaten a vessel as large as Shinano. At 10:45 p.m.. Lookouts sighted the archer fish on the surface. The destroyer is Isokaze.

Disobeying orders, moved into attack. Abe quickly ordered it back into formation. He suspected a decoy bait meant to lure his escorts away so other American subs could strike to avoid the trap. He ordered a sudden turn to the south. Confident he could outrun the pursuer. By his calculations, Shinano held a 1 to 2 knot speed advantage over the American boat.

Archerfish’s engines roared at full throttle. Driving at a top surface speed of 18 knots. As she strained to keep pace, Captain Enright quickly drew a sketch of the vessel, but by 11 p.m., the American crew watched helplessly as the targets slipped beyond visual contact. Enright, haunted by memories of the Shikaku slipping from his grasp, made a bold choice stay the course.

He gambled that the mysterious carrier, originally tracked on a 210 degree southwesterly heading, might swing back and resume its original path. If it did, Enright wanted to be ready. As time slip by, so did the Shinano were plowing south, refusing to correct her course, patting the rosary beads in his pocket. Commander Enright grew increasingly anxious, unable to find his target.

Around 11:22 p.m., prayers were answered. One of Shinano’s propeller shafts began to overheat, forcing the carrier to reduce its speed to 18 knots, matching closely the top speed of the archer fish. Then, at 11:40 p.m., with a faulty engine and under the illusion of safety, Captain Abe changed course, turning the Shinano due West, believing he had left danger behind the Archerfish.

Now just south of the Shinano, suddenly regained contact. From here on and right rode later. It was a mad race for a possible firing position. Shinano’s speed was about one not in excess of our best, but his zigzag plan allowed us to pull ahead very slowly, tracking just ahead, but not close enough to attack without being spotted.

Enright grew frustrated. He radioed a contact report to Pearl Harbor, transmitting the Archerfish’s location, heading an intended target for any American subs in the area. The Japanese picked up the transmission almost immediately on the bridge. Captain Abe listened as the foreign signal broke through to him. It confirmed his suspicion they weren’t being tracked by one submarine, but many.

Unfortunately for Abe, his hastily constructed ship was not fitted with the equipment needed to ascertain the distance or bearing of intercepted broadcasts. So he imagined a wolfpack of American submarines waiting north, just out of sight, plotting their ambush. At 2:56 a.m., Captain Abe, frightened, made a sharp turn to the southwest, resuming Shinano’s original 210 degree course that Enright was hoping for.

The massive carrier was now heading directly toward Enright. He quickly turned his ship across the Shinano’s new track, and at 3:05 a.m., Archerfish dove beneath the surface and moved into an attack position, leveling the sub at 60ft. Flood. The tubes, set depth on the torpedoes ten feet, and Enright ordered. Some of the crew looked puzzled.

Ten feet seemed unusually shallow, but Enright wasn’t guessing. He was remembering a year earlier. Rear Admiral Freeland Daubin had told him, if you’re going after a carrier hit just beneath the waterline. The weight of the flight deck could do far more to roll a carrier than simply punching holes anywhere on the hull.

Enright also knew something else. His Mark 14 torpedoes had a reputation for running deeper than their settings. Immediately, something changed aboard Shinano for hours. They had heard consistent radar pings echoing from the American boat. Now the pulses were gone. Silence. Captain Abe knew what that meant. The enemy sub had submerged.

An attack was coming. Trying to shake the enemy. He ordered another frantic course correction, this time heading due south. Captain Abe had inadvertently turned his ship broadside to the Archerfish. By 3:13 a.m., the distance between the two vessels had closed to just under two miles. Archerfish, now deep below periscope depth, carefully threaded its way through the destroyer screen, with one destroyer passing just ten feet overhead, its prop washed violently, shaking the sub.

Luckily for the Americans, the destroyers sonar was inoperable for recent battle damage, and she calmly churned past when the propeller was faded. Archerfish crept back up to periscope depth for one final check. Shinano loomed large in the lens. Without hesitation, Enright gave the order. Fire one! The firing plunger slammed down.

Then again and again, four torpedoes launched, spaced eight seconds apart. The crew scrambled, reloading the tubes. Two more torpedoes fired into the night, and Enright kept his eyes fixed on the periscope. Then impact. Two brilliant flashes lit up Shinano’s starboard hull. But he couldn’t linger. Take her down 400ft.

Rig for depth. Charge! Attack! He shouted. The sub dove deep as two other torpedoes slammed into the carrier’s side above. The giant Supercarrier shook violently. Alarms blared across the ship on the bridge. Captain Abe felt it instantly. They’d been hit. It was bad, but not catastrophic for torpedo hits, in theory.

Shouldn’t be enough to sink a vessel of Shinano’s size and armor. But on the bridge, Captain Abe stared out the forward window. The ocean was tilted. The armor had failed. Damage reports flooded in, and none of them were good. The torpedoes had struck high just beneath the surface, where Shinano’s armor was the weakest.

The first torpedo tore open an empty fuel tank and the refrigeration plant. Both compartments flooded instantly. The second obliterated the starboard engine room. Water surged in the third ripped into fire. Room number three, killing every man inside and spilled across into five rooms one and seven. The fourth punched through the starboard air compressor room, disabling the number two damage control station.

Each hit shallow but devastating. What was meant to be the unsinkable war machine was quickly taking on water. At 4 a.m., Captain Abe could barely stand. The Shimano was listing hard at 13 degrees and worsening. Gripping the bridge’s rail, he gave the order. We’re going to try for zero point. Do everything you can to right the ship below deck.

Chaos reigned. Damage control crews scrambled to patch ruptures, but their efforts were slowed by hundreds of panicking civilians and conscripted Korean laborers, unable to understand commands being shouted in Japanese. Desperate, Abe gave orders to keep the engines at full speed, not just to flee any lurking submarines, but to outrun the sinking.

But the very force driving Shinano forward was pulling her under at 18 knots. Seawater roared through the open wounds in her hull. By 6 a.m., the list worsened to 20 degrees. The portside seawater intakes were now above the waterline, cutting off the ship’s ability to counter flood. Soon the freshwater system collapsed.

Without it, the boilers began to shut down. She now limped through the sea at under ten knots. In a desperate attempt to get closer to shore. Captain Abe ordered the destroyers Hamakaze and Isokaze to take the carrier in tow. But the immense weight of the sinking ship was too much. The tow cables began snapping, whipping violently back against the deck, and her crew.

Dawn broke over the Pacific as the Shinano crawled. In the five hours since the torpedo strike. She traveled a little over 36 miles as compartment after compartment filled with water. At 8 a.m., in one final desperate gamble, Abe gave the order to deliberately flood the portside boiler rooms, hoping to counteract the increasing list.

For a brief moment, the ship stabilized, but the ocean wasn’t done. By 8:30 a.m., the situation had reached its breaking point. The starboard side hydraulic pump room, already straining under the pressure, flooded entirely. In his final moments, Lieutenant Inada, still at his post, picked up the voice pipe to the bridge and offered his final words.

I go before you. I will pray for Shinano and her crew. By 10 a.m., over a thousand men were crammed onto the flight deck, clinging to railings as the list passed 20 degrees. See now lapped at the base of the island structure, there was nowhere else to run from the bridge. Captain Abe, unable to utter the words abandon ship, simply said, you are all released from duty.

Save yourselves! And at 10:55 a.m., the 71,000 tonne Supercarrier rolled onto her starboard side and slipped beneath the waves. Trapped air pockets exploded from the hull, sucking hundreds of men down into the ship’s final plunge. Captain Abe remained aboard with his senior officers choosing to go down with the ship he had brought to sea aboard the nearby destroyer Yukikaze.

Captain Terauchi issued a chilling order to his executive officer, Lieutenant, do not pick up any sailor who cries or calls for help. Such faint hearts are of no use to the Navy. Rescue only those who stay calm and courageous. Many more men drowned than were rescued. By 2 p.m., the search for survivors was called off.

Of the 2515 people who had set out aboard Shinano, who more than half perished, losing 1455 souls. The submarine that had delivered the fatal blow, USS Archerfish was already gone, slipping silently into the vast Pacific. She returned to Guam on December 15th, 1944. Her patrol, complete and undamaged. But when Commander Joseph Enright and his crew came ashore, they were met with skepticism.

Operations Officer John Corbus pulled Enright aside. I’m sorry, Joe, he said, but naval intelligence won’t back your claim. They say there wasn’t any carrier in Tokyo Bay, so how could you have sunk one? Enright was stunned, so he handed over his pencil sketch, a drawing made during the pursuit. One image in particular stood out a rounded bow.

It matched the silhouette of a long rumored Japanese supercarrier. A secret ship never confirmed until now. Shortly after, a Japanese radio message intercepted back in November confirmed it, Shinano was sunk. Naval analysts estimated Shinano’s displacement between 59,000 and 72,000 tons, making her the largest warship in history ever sunk by a submarine.

The Navy would later declare and writes mission the most successful submarine patrol of the war by tonnage destroyed. For his actions, Captain Enright would later go on to receive the Distinguished Navy Cross. In Japan, Shinano’s loss sent shockwaves through the Imperial Navy. The carrier had been a cornerstone of plans to revive Japan’s naval air power.

Its destruction was devastating, not just strategically but symbolically to preserve morale. The sinking was kept secret for months. Survivors were quietly moved to facilities near Kure, locked away from the public. Shinano’s legacy is one of paradox, the most massive aircraft carrier of her time, and yet also the most short lived.

She was a bold gamble, a desperate shift in naval doctrine converted mid construction from a battleship. After midway, her redesign was rushed. Compartments left unsealed, damaged crews undertrained. It wasn’t just torpedoes that sank her. It was unfinished work and the pressure to move forward. Ready or not, strategically, her loss changed nothing.

Symbolically, it shattered any illusion of Japan’s naval resurgence in the decades since, naval engineers, historians and tacticians continue to study Shinano for what her failure teaches about overconfidence, about bureaucratic pressure, about the dangers of haste in wartime, and about how even the largest ship, with all its armor and promise, can be undone by the smallest of cracks.

If no one takes time to fix them. In the end, Shinano never truly served.

News

“Where do you think you’re going?! Your guests have arrived!” the mother-in-law exclaimed—only to get exactly the answer she deserved.

Anna carefully parted the curtain and looked out the window. The familiar white Logan pulled up to the gate, and…

The husband left for a younger woman, leaving his wife with enormous debts. A year later, he saw her behind the wheel of a car that cost as much as his entire company.

“I’d leave you the keys, but there’s no point.” Elena slowly raised her head. Andrey was standing in the doorway,…

CH1 THE ENTIRE World War II From The German Perspective | Documentary in PURE COLOR

When Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Germany was still bound by the impositions of the Treaty of…

CH1 Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

four hundred planes vanished 400 aircraft launched into the Pacific sky only a handful returned what happened on June 19th,…

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

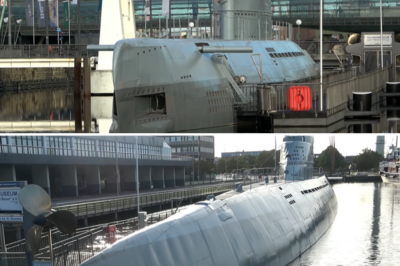

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

End of content

No more pages to load