When Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Germany was still bound by the impositions of the Treaty of Versailles, which had limited the country’s military capacity. After the defeat of 1918, the German army, known under that agreement as the Reich, was restricted to 100,000 men with no tanks, no heavy artillery, no combat aviation, and a navy reduced to small ships.

The prohibition of a formal general staff forced military planning structures to be camouflaged under organizations with other names and arms production was subject to strict international surveillance. However, even before Hitler came to power, there was a clear determination among the military leadership and nationalist sectors to overcome these limitations and rebuild war potential.

What changed with the arrival of the national socialist regime was the speed, scale, and political determination to transform these aspirations into concrete actions. In the first months of his reign, Hitler presented his rise as the beginning of a new era for Germany.

Propaganda insisted that the people had regained strong leadership and that the country must free itself from the humiliation imposed by the victors of the Great War. Although Germany ostensibly continued to respect the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, in reality, discreet measures began to promote rearmament which took place under administrative cover and public works programs.

In these initial steps, the objective was to avoid direct clashes with the Western powers while preparing the ground for greater military expansion. Clandestine rearmament was not an entirely new phenomenon as secret links with the Soviet Union had been maintained since the Vhimar Republic, allowing weapons testing on Russian territory far from international supervision.

However, under Hitler’s government, these practices expanded and were integrated into a coherent plan linking economic reconstruction with war preparation. Job creation in arms factories and public works was presented as a social policy, but in practice it meant the development of an industrial infrastructure ready to support military production. A turning point came in 1935 when Hitler openly announced the introduction of compulsory military service transforming the Reich into the Vermacht.

The army was organized into larger divisions and the formation of armored and motorized units began. That same year, the Luftwaffer, already secretly developing, was officially established, and massive resources were invested in the creation of a modern military aviation system. The cremine, although more limited for budgetary and strategic reasons, also began a process of expansion with new submarines and plans for a stronger surface fleet. The here, as the land army was called, was the first to expand.

From the 100,000 men permitted by Versailles, the force grew to several million in just a few years. Infantry, panza, and motorized divisions were organized, giving the army greater flexibility and mobility than in the previous war. Officer schools were reactivated and doctrines were developed that sought to avoid the positional warfare that had characterized the conflict from 1914 to 1918.

Instead, the idea of a quick war was promoted in which armored vehicles and aircraft would play a central role. The Luftvafer under the leadership of Herman Guring became one of the most visible symbols of Germany’s new military power. From its earliest years, it focused on the production of fighters such as the Messmitt BF 109 dive bombers such as the Junker’s J87 Stooker and medium bombers such as the Hankl 111.

These models were designed not only to match the capabilities of other powers, but to shape a style of warfare in which aviation would directly support ground forces, striking enemy concentrations and disrupting their defenses. The Luftvafer was not born as an independent strategic weapon, but as an integral part of a Blitz Creek plan.

The Creeks marine, for its part, faced greater limitations. Germany could not compete in terms of ship numbers with the British Royal Navy, so it opted for a development centered on Ubot. In 1935, a naval agreement was signed with Great Britain that in theory set limits on the German fleet, but in practice was used as a justification for expanding naval construction.

The most ambitious plan known as plan Z called for the construction of large battleships and aircraft carriers. Although by the outbreak of war only a portion of that program had been completed. Meanwhile, Yubot offered a tool of asymmetric warfare capable of threatening enemy supply routes in the event of a conflict.

The development of this military machine was accompanied by a doctrinal framework that sought to avoid the mistakes of the previous war. The experience of the trenches and stalemate had left German officers with the conviction that the next conflict must be resolved quickly and with the coordinated use of all available means.

Thus was born the idea of blitzkrieg or lightning war which was not a single plan codified in a manual but a set of principles that prioritized surprise, speed and coordination between forces. The army was to penetrate enemy lines with tanks and motorized troops while the air force destroyed key points and disrupted the rear guard.

The infantry would advance behind to consolidate the positions gained. This combination was intended to destabilize the enemy from the outset and prevent them from having time to reorganize. Blitzkrieg represented a break with the classic view of attrition warfare.

Instead of relying on the accumulation of forces to slowly wear down the enemy, it aimed to achieve a rapid collapse of its capacity to resist. This required meticulous planning, efficient logistics, and coordination between branches that had previously been unseen on such a scale. Although the vermar was still in the process of formation in the second half of the 1930s and lacked many of the necessary resources, the doctrine was consolidated as the basis upon which officers and troops were trained.

Politically, Hitler combined these measures with a public discourse that continued to speak of peace and a just revision of the international order while in practice directing all of the state’s resources toward rearmament. Financial mechanisms such as the so-called mephoexel were used. Bills of exchange issued by a fictitious company that allowed arms production to be financed without appearing in official budgets.

This financial engineering concealed the real pace of rearmament, avoiding an immediate economic collapse while allowing a massive military expansion. The organization of the economy was adjusted to the needs of the military. Heavy industry, steel production, and research into new fuels and synthetic materials were placed under state control.

Agriculture was also adapted to the expectations of self-sufficiency, seeking to ensure food supplies in the event of war. The 4-year plan, launched in 1936, was the clearest expression of this policy. Its objective was to prepare Germany for war in the short term, reducing dependence on imports and ensuring the capacity to sustain a prolonged conflict.

The German military command, although occasionally reticent about the pace imposed by Hitler, gradually aligned itself with these objectives. Generals who had experienced the First World War understood the risks of a premature conflict. But the regime’s authority and initial foreign policy successes reinforced confidence that Germany could once again confront Europe.

The army, which during the Vhimar years had sought to maintain a low profile, became the central pillar of a state that conceived itself as a militarized community. Internationally, these measures generated concern among neighboring powers.

But the policy of appeasement and the desire to avoid a new war allowed Germany to continue expanding its capabilities without encountering immediate opposition. Thus, by 1939, the Vermacht had become a force of several million men equipped with modern divisions, a large air force, and an expanding navy. What had begun as rearmament disguised as a social program, was transformed into a war machine ready to be deployed.

The Reich’s big lie, the pretext for invading Poland and starting the war. Since the spring of 1939, the German high command no longer discussed whether to attack Poland, but when. Planning began to take concrete shape in April when Hitler issued instructions for swift and decisive action against the eastern neighbor.

The objective was not solely military. It was about imposing a definitive solution to the Polish problem, which for the regime was both territorial and ideological. The guidelines were clear. Eliminate Poland’s defensive capacity from day one.

Destroy its administrative structures and make it clear that this was not a temporary campaign or a partial occupation. To achieve this, the German army needed meticulous organization. By mid year, plans were finalized for what would be the fastest campaign Europe had yet seen. Forces were concentrated at several strategic border points. The Vemar had overwhelming forces at its disposal. Around 1.5 million men, almost 2,500 tanks, and more than 2,000 aircraft were ready to participate in the offensive.

This mobilization included the here, the Luftvafer, and the criggs marine, although the latter had a more limited role due to the land-based nature of the conflict. Tactical preparations included strong coordination between ground and air forces. The concept of blitzkrieg, which had already been developed in previous years, found its first practical application in this operation.

Although it was not a formally established doctrine as it would later become, the idea of combining rapid, deep, and wells synchronized attacks with intensive use of aviation was key. The Panza divisions supported by tactical aviation would seek to penetrate the interior of the country as quickly as possible, avoiding conventional defensive lines and sewing confusion in the enemy rear guard.

The regime not only prepared the military aspect. Weeks before the attack, a propaganda apparatus was deployed to justify the action. Messages were crafted that portrayed Poland as a potential aggressor, and border incidents were exaggerated to generate an atmosphere of imminent threat. One of the most notorious fabrications was the Glyitz incident, a covert operation carried out by German forces disguised as Poles, simulating an attack on a German radio station.

This event was presented to the world as a Polish provocation and served as an immediate pretext for launching the offensive. At 4:45 a.m. on September 1st, 1939, the attack began. The Luftvafa bombed strategic positions in the Polish interior, including airfields, communication centers, and military warehouses.

Almost simultaneously, ground units crossed the border on multiple fronts with encircling movements that sought to disorganize the enemy from the first minutes. The Panza divisions advanced at high speed, flanked by motorized infantry that secured the conquered areas. The attack was devastating. Within days, the Polish defenses began to collapse.

German forces did not pause at points of resistance, but instead surrounded them and continued inland, leaving the mopping up and consolidation tasks to the rear guard. This strategy allowed for a continuous advance without exhausting forces in protracted engagements. Polish units, although they offered resistance at various points, were unable to coordinate effectively or establish a coherent defensive line.

Furthermore, German air supremacy hampered any attempt at reorganization or counterattack. Meanwhile, propaganda within Germany spread the idea of a preemptive, necessary, and just operation. Alleged abuses committed by Poland against German minorities on its territory were highlighted and the Reich was portrayed as a victim forced to defend itself.

Hitler’s speeches constantly repeated this narrative, asserting that all diplomatic avenues had been exhausted and that the attack was an inevitable response to Polish provocations. The news reels featured carefully selected images of smiling soldiers, columns advancing unopposed, and towns supposedly welcoming the German troops.

Coordination between the various branches of the military was fine-tuned in real time. Mobile divisions communicated their progress and requested air support when they encountered resistance. The Luftvafer responded swiftly, removing obstacles and allowing the advance to continue unabated. This breakneck pace surprised not only the Poles but also international observers.

Within a few days, German forces were deep inside enemy territory surrounding Warsaw and other key cities. On the diplomatic front, Germany had previously assured that the Soviet Union would not intervene on behalf of Poland. This was made possible by the pact signed in August between the two powers, officially known as the non-aggression pact, but which included secret clauses on the partition of Polish territory.

With this agreement, Hitler eliminated the risk of a two-front war and could concentrate exclusively on the Eastern campaign. Furthermore, he was confident that France and Great Britain would not react strongly as had happened in previous episodes. However, the diplomatic calculation was not entirely correct.

On September 3rd, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany, fulfilling their commitments to Poland. Despite this, no immediate military action was taken by these powers. For weeks, the so-called joke war raged in the West with minimal defensive movements and no significant fighting.

This allowed Germany to continue its offensive without worrying about a second front. Within German territory, the news of the war was received with a mixture of enthusiasm and resignation. Propaganda had prepared the ground, presenting the conflict as a just and necessary cause.

Many citizens supported the action, convinced that it was the only way to resolve the outstanding problems with Poland. At the same time, censorship and information control measures were activated to ensure a single narrative and prevent dissenting voices. Values such as sacrifice, discipline, and national pride were promoted while casualties were minimized and the harshest aspects of the conflict were hidden.

The campaign was brief but intense. On September 17th, the Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland, fulfilling its agreement with Germany. This further accelerated the disintegration of the Polish army, which was already in retreat.

Warsaw held out until the end of the month, but finally capitulated after a siege accompanied by constant bombardment. The Polish resistance was valiant in many instances, but completely overwhelmed by the enemy’s technical and organizational superiority. By the end of September, the map of Europe had changed. Poland was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union, and the world had formally entered the war.

For the Nazi regime, the campaign was a demonstration of military effectiveness, strategic planning, and political control. It confirmed that the rapid war model worked, and this reinforced the high command’s confidence in future operations. Blitzkrieg was not yet a familiar word to the public, but its essence had been put into practice with brutal efficiency. The experience in Poland became a model to follow.

Generals studied every detail of the operation to fine-tune the mechanisms for future campaigns. Political authorities highlighted the results as proof of the superiority of the German system. Parades were organized. Victory bulletins were distributed and the figure of the German soldier was glorified.

The initial success reinforced the idea that the Reich had an inevitable and justified expansionist destiny and that obstacles would be overcome with the same speed and determination as in this first campaign. Thus began from the German perspective a conflict that had not yet revealed its true colors, but which already revealed the determination of a regime willing to use all its resources to achieve its ends.

The invasion of Poland not only marked the beginning of the world war but also the starting point of a way of waging war where speed, surprise and propaganda were as important as weapons. Lightning victories, the Blitzkrieg and the rise of the Vermachar. German military strategy in 1940 focused on leveraging speed and coordination as the primary tools for victory.

After the campaign in Poland, the German army turned its attention westward, aiming to conquer France and its allies through an offensive that broke with traditional methods of attrition warfare. The concept of Blitzkrieg, which had already proven effective in Poland, was now applied on an even grander scale and with a precision that took the Western powers by surprise. The idea was simple but devastating.

Rapid, deep, and coordinated air and ground penetrations to disorganize the enemy before it could react. In May of that year, the Vermachar launched its attack on the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, nations that were inshed in the German military machine as part of the plan to outflank the French defenses.

The Majino line built by France to resist an invasion from the east, was rendered useless when German forces avoided directly confronting it and instead pushed through the Arden, a forested region considered unsuitable for mass movements. This tactical choice was key. The Panza divisions managed to quickly open gaps, pushing the Allied forces northward and cutting them off from their rear. The Netherlands could not hold out for long.

The German advance, accompanied by intense bombardment, caused the rapid collapse of the Dutch army. Rotterdam was bombed as a warning and the threat of total destruction forced surrender. The speed of the offensive and the brutality of the impact paralyzed any possibility of a coordinated response. Belgium, which had also attempted to remain neutral, was similarly overwhelmed.

Belgian, British, and French forces attempted to form a defensive line, but well-calculated German maneuvers backed by unprecedented mobility engulfed them before they could establish a firm front. The most decisive operation was the advance through Sedan. There, the Germans managed to quickly cross the Muse River, overcoming the French defenses.

Once this crossing was achieved, the armored divisions launched a westward thrust toward the English Channel, encircling the Allied forces in Belgium and Northern France. The rapidity of the movement left Allied commanders with no time to regroup, causing a collapse in morale and the command structure.

Dunkirk then became the only escape point. As British forces and part of the French army were trapped against the coast, an emergency evacuation was organized. Although the Germans could have closed the encirclement, they paused briefly at the decision of the high command, allowing hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers to escape by sea.

This tactical pause is still debated, but it did not change the overall course of the campaign. France was divided and its forces overwhelmed. The government collapsed under the speed of the German advance. Paris was occupied without prolonged fighting and in June, the country requested an armistice.

The victory was complete from a military point of view with a swiftness that completely broke with memories of the First World War. The success of the Blitzkrieg was not only operational but also propaganda based in Germany. The regime took advantage of this victory to reinforce the image of the invincibility of the new German army and the superiority of the national socialist system.

The images of the parade in Paris and reports of the advances were widely broadcast on the radio and news reels. Hitler appeared as a brilliant leader who had overcome the old powers while the generals were presented as national heroes. This narrative strengthened the country’s internal cohesion.

The population still fresh in the memories of defeat in the great war and the humiliations of the Treaty of Versailles experienced this moment as a historic revenge. Morale rose to unprecedented levels and confidence in the political and military leadership was consolidated.

The idea was established that the Reich could prevail in Europe with a combination of strength, speed, and determination. On the military level, the campaign served as a complete validation of the German model. Armored units operating in combination with aviation and efficient logistical support demonstrated that the war could be resolved in weeks, not years.

The Luftwaffer played a pivotal role weakening enemy forces and facilitating ground movements. German commanders watched with satisfaction as their doctrine was implemented with precision and effectiveness. Unified command, tactical surprise, and mobility were decisive factors.

The enemy, trapped in rigid defensive strategies and slower command structures, was unable to adapt to the pace of the offensive. This difference in approach marked the outcome of the campaign. Press reports spoke of the technical skill and bravery of the German soldiers without mentioning the level of coordination required. Mistakes made or missed opportunities as at Dunkirk were also omitted. Everything was presented as part of a perfect calculated sequence. The narrative was clear.

The new German army, rejuvenated and professionalized, was invincible. German cities celebrated the victory with parades, speeches, and a national exaltation that left the years of crisis behind them. A sense of renewed power was consolidated, that history was being successfully rewritten, and that the new Germany had completely overcome its recent past. The German high command, for its part, drew very concrete conclusions.

The success of the Blitzkrieg was interpreted as a repeatable formula, not a favorable exception. This optimism directly influenced the planning of subsequent operations. It was assumed that applying the same logic, any front could collapse with the right pressure.

This confidence in tactical superiority would be a determining factor in future decisions both in the east and elsewhere. The French campaign not only expanded the Reich’s territorial control, but also transformed the perception of the conflict. For many within the regime, this victory confirmed the idea that the fate of Europe was in German hands and that speed and will were enough to defeat any enemy.

Army morale was at an all-time high. The experience of such a successful, swift, and seemingly clean campaign contrasted sharply with the memories of the previous conflict in which every meter of ground cost thousands of lives. Now the divisions returned as victors, admired and decorated.

The sense that the new type of warfare could be imposed without wear and tear, reinforced both the internal command structure and the confidence of the political leadership. This collective euphoria built on a lightning victory consolidated the myth of invincibility. From a logistical standpoint, the success was also interpreted as proof that the German war system could operate efficiently beyond its borders. Supplies, equipment repairs, and the continuous movement of troops operated without interruption.

Significant. This reinforced the idea that the Reich could sustain prolonged operations if it maintained control of the offensive tempo. The army, the population, and the leaders shared a unified vision. The model worked, the strategy was effective, and the war could be won.

This internal consensus was fueled by propaganda which left no room for doubt. Everything pointed toward continued expansion. Every step taken in 1940 seemed to confirm that the combination of political determination, technical capability, and offensive doctrine was sufficient to conquer Europe.

The reality of such a swift victory achieved with so little apparent resistance emboldened both the command and the people. Thus, at the close of that year, Germany was at the height of its confidence. The myth of the Blitzkrieg, now fueled by facts, defined the course of the conflict and set the tone for what was to come. The sky closes in. The failed attempt to subdue England from the air.

After the swift German victories in Western Europe, Hitler ordered the army to prepare a plan to invade the United Kingdom. This operation was dubbed Sea Lion. It was expected to be a natural continuation of the success achieved in France. However, this time the scenario was different. It was not an immediate ground offensive, but an invasion that required first dominating the air and sea space.

The German command knew it could not land troops on British soil without first neutralizing the Royal Air Force. Therefore, the high command ordered the Luftvafer to completely eliminate the United Kingdom’s air defense capability before setting a definitive date for the landing.

The Luftvafer had extensive experience from its previous campaigns and was convinced it would achieve its objectives without major difficulties. At the start of the air offensive, they focused on bombing military targets such as airfields, radar stations, and lines of communication. The goal was to systematically weaken British defenses. The attacks began in July 1940 and intensified in August.

Hundreds of cross-channel sorties were launched each day to attack the islands. However, the British had prepared a more robust defense network than the Germans had expected. In addition to having a radar early warning system, British pilots operated close to their bases while the Germans had to fly long distances which limited their combat time.

The German tactical superiority that had worked in ground campaigns did not translate easily to air combat. Although the Luftvafer had a large number of aircraft, its bombers were slow and vulnerable. The fighters tasked with escorting them had limited range, so they were often unable to accompany them to the end of their flight.

This left the bombers exposed to attack by British fighters, which took advantage of this weakness to shoot down large numbers of enemy aircraft. Despite the losses, the Germans continued their offensive, changing targets and adapting their strategy. For several weeks, they heavily attacked radar installations, hoping to blind the British defenses.

They then focused on destroying airfields, trying to leave the RAF unable to respond. Seeing that the Royal Air Force was holding out longer than expected, the Luftvafer adopted a new approach. At the beginning of September, the bombing raids were directed toward major cities, especially London.

This decision was not solely a response to military necessity. The aim was to instill fear, break the population’s morale, and force a surrender. But this new tactic failed to achieve its objectives. Although it caused destruction and civilian casualties, British resistance did not weaken.

On the contrary, the population adapted to the attacks, and British propaganda strengthened the collective spirit. Authorities distributed gas masks, organized shelters, and established evacuation systems for children. Meanwhile, British pilots continued to engage the Germans, often with numerical superiority, but with a closer knowledge of the terrain and a ready support network.

The German high command, seeing no clear results, began to question the effectiveness of their actions. Although initially confident of a swift aerial victory, as the weeks passed, their confidence began to wne. Aircraft loss figures were increasingly high, and production could not compensate for attrition. Furthermore, experienced pilots were becoming scarce.

In contrast, the RAF was able to replace its aircraft more quickly thanks to its war adapted industrial system and external aid. British fighters such as the Spitfire and Hurricane proved effective and squadrons were rotated to avoid exhaustion. The situation became even more tense when intelligence reports began to show that the air offensive was not achieving its stated objectives. Key British defense installations remained operational.

Airfields were being rapidly repaired and aircraft production had not halted. Rather than weakening the RAF, the campaign seemed to strengthen its resolve. This forced German authorities to reconsider the feasibility of a ground invasion. Although Sea Lion was not officially cancelled, it was indefinitely postponed and assigned units began to be redeployed for other duties.

Hitler, who until then had been confident of a favorable outcome, accepted that the United Kingdom would not fall through a rapid air offensive. The failure had a strong impact on the domestic perception of the conflict. In Germany, propaganda had been tasked with portraying military advances as inevitable. Each victory was heralded as proof of national superiority.

The offensive against the United Kingdom was presented as a further step toward consolidating the new European order. However, when it became clear that the objective would not be achieved, the tone began to change. Official communicates reduced attention to the campaign in England and began to highlight other issues.

The media stopped talking about Britain’s imminent collapse and began to present the bombing raids as a punitive measure or as part of a prolonged blockade. This change did not go unnoticed by the population, which had been accustomed to a narrative of constant progress. Internally, the German command looked for reasons to explain the failure.

Some blamed bad weather, others a lack of coordination between the branches of the armed forces. There was also criticism of the strategy adopted by Guring, who had promised that the Luftvafer would achieve complete control of the air without the need for naval support. His confidence in the abilities of his pilots and aircraft was not reflected in the results.

Divisions within the military leadership began to become more visible despite the experience accumulated in previous campaigns. This was the first time that the German army had not achieved its objectives immediately. The air conflict with the United Kingdom marked a turning point.

Although it did not halt the German war machine, it did show that there were limits to its advance. The failure in British skies also had technical consequences. Commanders began to rethink bomber design, seeking models with greater range and defensive capabilities. Escort systems, coordination between squadrons, and supply logistics were evaluated.

In parallel, alternative plans for future campaigns began to be developed. Authorities understood that they could not rely exclusively on one tactic or one type of weapon. While Blitzkrieg had been effective on the ground, in the air, it required adaptations that had not been anticipated.

The British experience demonstrated that an enemy with good technical preparation and the will to resist could alter the course of the war. Another important aspect was the response of the German population. Although there was no complete information about the results, it was clear that something had changed. The indefinite suspension of the ground invasion and the growing silence in the media generated uncertainty.

Propaganda attempted to maintain morale, speaking of a future victory or a diplomatic solution. But for the first time since the beginning of the conflict, doubts arose about the infallibility of the leadership. Some voices began to wonder whether the United Kingdom would be a more complex obstacle than anticipated.

These concerns were not expressed openly, but they were signs that the initial enthusiasm was beginning to moderate. Over time, the conflict with the United Kingdom faded into the background. strategic priorities shifted and it was decided to focus efforts on other fronts. Even so, the air battle left a permanent mark on military leadership.

It was a lesson in the limits of aviation, the importance of logistics, and the enemy’s ability to adapt. Although the German command attempted to present the campaign as a partial success, in practice, it was a setback. The failure to defeat the RAF or pave the way for a direct invasion prevented the Third Reich from consolidating its total dominance over Western Europe.

The Battle of Britain was an episode in which air strategy revealed its weaknesses. Unlike ground offensives, where conquered terrain offered visible results, in the air, everything depended on coordination, timing, and the enemy’s ability to respond. The Luftvafer discovered that having more aircraft or previous experience was not enough.

The combination of technical, tactical, and human factors determined the outcome. The British managed to hold their airspace, withstand the pressure, and preserve their operational capability. And that meant that Hitler’s most ambitious plan up to that point to conquer the United Kingdom would not be realized.

The air offensive against England was not only a strategic setback. It was also the first moment in which the German military machine encountered an obstacle it could not overcome in the expected time. The consequences were evident in the redesign of plans, the reorientation of resources, and the internal perception of the conflict.

The war would not be as swift or as one-sided as had been imagined. This episode demonstrated that organized resistance combined with adequate technology and strong morale could halt even an enemy that until then seemed invincible. The experience of that summer changed the pace of the conflict.

And although the Reich continued to advance on other fronts, it would no longer do so with the same certainty of immediate victory. Barbarasa, the invasion that promised to end it all. After the swift and crushing victory in Western Europe, the German command’s next strategic objective was already clearly outlined. For months, even before the fall of France, Hitler had expressed in closed circles his decision to launch a new campaign eastward.

In his calculations, confrontation with the Soviet Union was neither a remote possibility nor a response to external provocations. It was a necessary step to secure the living space that Germany, in the regime’s view, was to conquer and dominate. This long-standing idea was closely linked to the concepts of labramm and anti-communism.

The east, populated by Slavs considered racially inferior, was to be subjugated, its resources appropriated, and its lands colonized. Soviet communism, for its part, represented not only a rival ideology, but also an existential enemy that had to be destroyed at its roots. Planning for this operation began systematically after the summer of 1940.

Although Great Britain had not yet been defeated and remained an unresolved military issue, the high command began preparing plans for an invasion of the USSR. In December of that year, Hitler signed directive number 21 known as Operation Barbarasa. It explicitly stated that the Vermachar was to be ready to launch an offensive in the east by May 15th, 1941.

The instructions were clear. It was to be a swift campaign, dismantling the Red Army before it could retreat or mobilize its reserves. It was envisioned as a short, decisive, and devastating war, similar to the previous campaigns in the west, but on a much larger scale. The logistical deployment was immense.

Three large army groups would be responsible for advancing along a front of almost 3,000 km. Army Group North was to head toward Leningrad, Army Group Center toward Moscow, and Army Group South toward Ukraine. These were joined by auxiliary forces from allies such as Romania, Finland, and Hungary.

The combined effort constituted the largest military operation ever organized up to that point. More than 3 million German soldiers were mobilized, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of horses, thousands of tanks, cannons, and vehicles of all types. Preparations were carried out under a cloak of partial secrecy.

Although the troop volume did not go unnoticed, the Soviet government did not react immediately, perhaps relying on the non-aggression pact signed in 1939. On June 22nd, 1941, early in the morning, the invasion was officially launched. Troops crossed the eastern border without a prior declaration of war.

Heavy artillery and aircraft began a series of simultaneous bombing raids against Soviet airfields, command centers, and depots. The Luftwaffer managed to destroy a significant number of enemy aircraft on the ground during the first hours, which allowed German air superiority to be secured in almost all sectors. As tanks and motorized units advanced, infantry divisions followed behind, securing the occupied territories. The surprise was total.

The Red Army, poorly prepared and disorganized, offered no effective resistance in the first few days. Many Soviet units were surrounded and destroyed before they could react. Communication lines collapsed and chaos spread through the middle management. Within a few weeks, the Germans had penetrated hundreds of kilometers into Soviet territory, capturing tens of thousands of prisoners. Cities and towns fell one after another.

Army Group North advanced rapidly toward the Baltic, taking Ria and approaching Leningrad. Army Group Center carried out the largest pocket of destruction in Bellarus around Minsk and later in Smolinsk. Army Group South, although faced with greater difficulties due to geography and resistance, managed to advance through Ukraine and approach Keev. From Berlin, the regime’s tone was one of complete confidence.

Propaganda spread an image of absolute control, presenting the campaign as yet another demonstration of the Vermach’s invincible power. It spoke of a crusade against bulcheism, a civilizing undertaking, and a necessary preventive war.

Official bulletins highlighted the number of prisoners captured, the speed of the advance, and the apparent weakness of the enemy. It was asserted that the total collapse of the USSR was a matter of weeks. In the print and radio media, maps showed the new territories under German control and communicates from the high command spoke of unremitting victories.

The population received these messages with a mixture of enthusiasm, relief, and a certain sense of historical fatalism. For many Germans, the war in the east was not a simple continuation of previous conflicts, but a decisive struggle. Within the high command, however, there were nuances. Although an optimistic attitude generally prevailed, some officers expressed doubts about the logistical capacity to maintain the offensive momentum on such a wide front.

Supply difficulties, vehicle wear, and the need to secure rear lines were constant concerns. The speed of advance was simultaneously its greatest strength and its greatest risk. Every kilometer gained distanced units from their supply centers. Furthermore, Soviet resistance, although chaotic at first, was beginning to reorganize in some sectors.

At certain points along the front, enemy troops offered a more cohesive defense, slowing the German advance. Despite these indications, during the first months of the campaign, the numbers remained staggering. In the initial operations, more than half a million Soviet soldiers were captured in several pockets such as Minsk, Smolinsk, and Uman.

The territory under German control was growing rapidly. Panza divisions opened deep breaches in enemy lines, enveloping large contingents and causing constant breakthroughs. The German command believed that a couple more blows would be enough to force the fall of Moscow and disintegrate Soviet command capacity. The strategy remained based on the premise of a short war.

And within this framework, military objectives were prioritized over the systematic occupation of the terrain. Over the following weeks, the situation remained favorable for the invaders. The front continued to expand eastward, and German troops reached the Neper, the Deina, and other key natural lines.

Specialized engineering units built bridges and repaired railways to facilitate the advance. Fallen cities were quickly taken and in many cases found partially evacuated. Fear of the German enemy had spread among the local population. Although the occupation orders were marked by ideological hostility, the focus of the military command remained on securing the terrain and advancing.

The triumphalist rhetoric remained intact. In Berlin, Hitler’s public statements reflected his conviction that the campaign was in its final stretch. The idea that the Soviet Union was a colossus with feet of clay seemed to be confirmed by the lack of an effective defense.

In the first months, the message that communism would be eradicated and that history was witnessing a fundamental transformation of the continent was reinforced. The propaganda machine intensified its activity, presenting soldiers as ushers in a new era. Newsreal images showed tanks crossing endless planes, German flags waving in distant villages, and maps showing the front line steadily moving toward Moscow. The sentiment in Germany was for the most part one of confidence.

The population accustomed to hearing good news for almost 2 years assumed that this new campaign would be another demonstration of superiority. The figures offered in the communicates fueled that perception. Each bulletin reported thousands more prisoners, cities captured, and new advances. Posters and publications portrayed the Red Army as a disorganized, archaic, and unresponsive force.

Even those who harbored personal doubts about the duration of the conflict preferred not to express them openly. Social pressure, censorship, and the collective desire for victory maintained the cohesion of the official discourse. Meanwhile, troops continued to advance into vast Soviet territory.

The strategic objective of reaching Moscow before winter remained a priority. The advance continued unabated, and although increasing obstacles began to emerge, the conviction that victory was near continued to prevail in the high command. Decisions were made with the idea of a short campaign without considering prolonged scenarios. A war of attrition was not anticipated.

The conviction was that the USSR would collapse just as other countries had in the past. The message was clear. Operation Barbarasa was presented as a logical, inevitable, and justified undertaking. The propaganda left no room for ambiguity. It was a fight for Germany’s survival against an ideological, racial, and military enemy.

Every step eastward was in this narrative an affirmation of national destiny. The war effort was presented as rational, planned, and successful. The reality of the front with all its complexities had not yet transformed this dominant narrative. Between mud and death, the impossible routine of the Eastern Front.

From the moment the Vermachar crossed the Soviet border, German soldiers began to face conditions radically different from those experienced in previous campaigns. The space was immeasurable, the roads impossible, and nature showed no mercy. As they traveled deeper into Soviet territory, the daily reality of the Eastern front became more hostile. Fatigue accumulated not with the passing days, but with every meter traveled.

The mud clinging to their boots seemed to never dry, and their uniforms, worn from continuous use, no longer offered protection against the damp or the slashing wind. The mud and cold were just the beginning. They slept in open fields or destroyed farmhouses, always unsure whether the next day would bring a skirmish, a bombardment, an improvised retreat, or simply more miles of marching to nowhere.

Provisions planned with optimistic calculations soon began to run short. Many soldiers were forced to rely on local supplies, which rarely existed or had already been swept away. Field kitchens could not keep pace with the advances. Hunger became a constant, sometimes interrupted by theft, barter, or a lucky find.

Letters sent home hinted at this physical deterioration with phrases that spoke of exhausted bodies, empty stomachs, and days without hot food. At the same time, the cold penetrated everything. Blankets were not enough, and fingers froze upon contact with the steel of weapons. In winter, breathing became painful, and icy helmets burned the scalp.

In these extreme circumstances, fatigue was no longer merely physical. It became a mental fog that hampered decisions, slowing every movement. Sleep became a rare luxury, interrupted by distant gunfire, alarms, or simply the anxiety that kept the body on its toes. Routine was rife with fear, which never completely disappeared.

Even when the front seemed calm, the fear of an ambush, a mine, a sniper, or a sudden offensive haunted every step. There was no security. Some wrote that the most agonizing moments were the silent ones because they anticipated the unpredictable. The constant tension wore down even the most experienced soldiers who acknowledged in their diaries that the Eastern Front was something completely different from what they had experienced in other campaigns.

Official propaganda attempted to sustain morale with heroic tales, images of smiling soldiers and optimistic communicates. In German newspapers and news reels, reports spoke of successful advances, captured cities, and a collapsing Soviet resistance. But those on the front lines saw something else. The destroyed cities offered neither shelter nor resources.

The evacuated or annihilated populations left behind desolate landscapes. Casualties mounted, and the terrain, far from offering control, was a field of constant tension. Some soldiers kept pamphlets with motivational phrases that no longer spoke to them. The distance between the official account and actual experience became evident every day.

Even so, many did not allow themselves to openly doubt. They clung to what they knew, repeated their officers’ words, and believed in ultimate victory as a psychological refuge rather than a strategic certainty. Family letters played a crucial role as receiving news from home was one of the few consolations available.

These messages, though brief, managed to suspend the feeling of abandonment. But even in them, the soldiers began to filter their disenchantment through veiled phrases that evaded censorship, yet clearly conveyed the emotional burden of the front.

Some spoke of the difficult life here, of endless nights, or of a land without end, while others more explicitly confessed their fear, frustration with the conditions, or incomprehension at the slow progress. The shared experiences among comrades were also ambivalent. While strong bonds were built, tensions also arose.

Fatigue generated arguments, friction, and hopelessness, and not everyone endured equally. Some turn to alcohol when available, others to isolation or erratic behavior. Although formal discipline was maintained, the command was already noticing the symptoms of an army that, although operational, was beginning to show signs of profound wear and tear. The geographical distance was also evident in communication with the high command.

Orders arrived late or were contradictory and was sometimes based on maps, inaccurate or outdated assumptions. The reality on the ground contradicted the reports from Berlin. The enemy, which should have collapsed within a few weeks, continued to fight. Soviet units reorganized, counterattacked, and forced positions back. and each new attempt to advance demanded more resources, more energy, and more lives.

The initial enthusiasm that had accompanied the start of the operation had completely faded. Euphoria gave way to exhaustion, and the feeling of invincibility was no longer a topic of conversation. In its place was a resigned acceptance of the harshness of the Eastern Front, marked by a routine based more on endurance than on the expectation of immediate success.

In this context, some took refuge in personal beliefs, rituals, or superstitions. They crossed their fingers before going out on patrol, repeated phrases before going to sleep, or carried amulets and family photos hidden in their pockets as a way of feeling less alone and retaining some control amid the general disorder.

The emotional distance from the rear guard also increased. What they experienced at the front was difficult to explain, even difficult to accept. Some soldiers began to feel that no one except their comrades could understand what they were going through. That feeling of isolation deepened with each week. Expectations of a quick return had faded.

Return was no longer spoken of with precise dates, but rather with phrases like when this is over or if we get through this. Time became an elastic concept. The days were all the same and the clocks seem to stand still. Only the seasons marked a change and sometimes not even that.

Some soldiers documented their experiences in personal diaries hidden among their clothing or luggage. And these writings, sometimes brief and sometimes longer, offered a more intimate and raw look at what was happening. They spoke of the fear of sleeping, of wounded comrades who couldn’t be evacuated, of marches that lasted more than 12 hours without a break.

There were also reflections, doubts, and long silences interrupted by phrases like, “This is not what we imagined.” although few dared to say them out loud because the weight of discipline, propaganda, and ideological mandate remained. Even so, the gap between the image of the front projected in Berlin and what was actually experienced was increasingly evident to those who were there.

Life on the Eastern front could not be compared to any previous experience of the Vermachar as it was an environment that slowly eroded the will and tested each man’s physical and psychological endurance. In that immense and hostile landscape where the enemy was not only the other army but also the climate, the mud, the disease, and the loneliness, the German soldiers kept moving forward because they had no other choice.

Germans against Hitler, those who dared to resist. From the early years of the Nazi regime, there were individuals and groups who, although isolated, began to express their doubts or rejection of the imposed policies. Some did so silently, avoiding showing loyalty in public.

Others dared to express opposing opinions in private circles. As the war progressed, these scattered gestures took on new forms and, although small in number, gave rise to pockets of opposition that could not be ignored by the authorities. Among the most active groups were young students, intellectuals, and members of the church. Small groups emerged in universities that analyzed the country’s situation with a spirit of solidarity.

Critic, one of the best known was the White Rose group, made up mainly of Munich students such as Hans and Sophie Schaw. These young people wrote and distributed pamphlets questioning the atrocities committed, especially on the Eastern Front, and appealed to citizens moral consciences to resist the regime.

They did not propose an armed revolution, but rather an ethical awareness. The state’s reaction was immediate and brutal. They were arrested, interrogated, and sentenced to death in summary trials. At the same time, other young people without university affiliations expressed their discontent on the streets.

The so-called Idle Vice Pirates, youth groups that rejected party discipline and compulsory indoctrination, began organizing clandestine meetings, disseminating banned songs, and sabotaging Hitler youth activities. They were not organized into a formal structure, nor did they seek to overthrow the regime, but their mere existence represented a challenge to the imposed uniformity.

Some of their members were arrested, others executed without trial. The church also offered spaces for disscent, albeit limited. Both Catholic and Protestant sectors attempted to maintain a certain doctrinal independence. In some cases, religious figures spoke out against forced euthanasia or racial persecution.

Catholic Bishop Clemens von Garland, for example, delivered sermons openly criticizing the murders of disabled people. Although he was not arrested, many of his collaborators were, and the Gestapo closely monitored his activities. Within the military ranks, there were also elements who began to doubt the direction the country was taking.

Some officers, disillusioned with the course of the war or shocked by the crimes witnessed in the occupied territories, began to secretly plot. These concerns eventually materialized in the most ambitious and organized attempt to eliminate Hitler, the assassination attempt of July 20th, 1944. Led by Klaus Fon Stafenberg, an army colonel, the plan was to plant a bomb in the Fura’s headquarters, eliminate the party leadership, and establish a government that would seek peace negotiations. The operation was carefully designed and involved numerous

high-ranking military personnel. The device exploded as planned, but Hitler survived with minor injuries. The coup collapsed within hours. The regime’s response was immediate. Mass arrests were ordered and purges were implemented within the army and civil administration.

More than 5,000 people were arrested, many with no direct connection to the attack. The executions continued unabated. Some were hanged with piano wire, others were beheaded, and many were tried in proceedings that were in reality mere formalities. Images of the trials were filmed and used as a tool of intimidation. The repression was not directed solely against the perpetrators of the attack, but also extended to their relatives, friends, and collaborators, whether real or merely suspected, applying the principle of collective responsibility. If an individual was accused of treason,

his immediate circle could also be punished under a logic that sought to eradicate any possible future outbreak of disscent. The message was direct. There would be no tolerance for the slightest gesture of opposition within German society. Perception of these acts was uneven as a significant portion of the population influenced by propaganda and subject to strict censorship accepted the official version which portrayed the conspirators as traitors and cowards.

Public speeches were given extolling absolute loyalty to the furer and demanding exemplary punishment. However, in certain sectors, especially among those directly suffering the consequences of the war, doubts began to arise. Some saw these acts as an expression of desperation, while others interpreted them as proof that not everyone shared the direction the country had taken. The regime’s propaganda reacted by adapting.

On the one hand, it reinforced the image of national unity and unwavering loyalty, portraying Hitler as the victim of a conspiracy of traitors. On the other hand, it intensified its rhetoric against internal enemies, comparing opponents to saboturs and spies. Posters were distributed, public events were organized, and campaigns were launched to denounce any suspicious behavior. Surveillance became omnipresent.

At the same time, the experience of the attack had repercussions on the inner circle. Hitler, deeply affected by what had happened, grew increasingly distrustful. He further distanced himself from his advisers, reorganized his security detail and ordered new protocols to prevent any similar attempt.

His relationship with the vermarked became more strained. The powers of the SS increased and oversight bodies multiplied. The memory of those who dared to resist, from the student leafletter to the soldier who risked his life in an impossible conspiracy remained fragmented throughout the conflict. Some were immediately forgotten.

Others were portrayed as traitors for years. Only much later after the collapse of the regime did they begin to be recognized as symbols of a conscience that although a minority was not completely extinguished. Internal disscent in Nazi Germany failed to alter the course of the war.

But it revealed that even under one of the most repressive regimes in history, there were voices willing to question, challenge, and resist. Amidst fear, absolute control, and omnipresent propaganda, there were those who chose another path, even though they knew their decision would almost certainly lead to their death. Total war and the Reich economy.

As the conflict escalated on all fronts, and the possibility of a successful blitzkrieg disappeared, the Third Reich was forced to completely transform its economic structure. As the scope of the war expanded, the need for systematic mobilization of all resources became unavoidable.

During the early years, the regime had maintained an ambiguous policy, avoiding deep interference in the civilian economy. However, the failure to quickly crush the Soviet Union and the entry of the United States into the conflict in 1941 necessitated a drastic shift. This transformation culminated in the policy of total war that was vigorously deployed from 1943 onwards when the German productive apparatus was completely subordinated to the war needs of the state.

The person in charge of this reorganization was Albert Spear appointed minister of armaments after the death of Fritz Tot. Although he was not a traditionally trained engineer, his closeness to Hitler, his administrative ability, and his willingness to centralize decisions made him the face of the regime’s technical efficiency.

Under his leadership, profound reforms were implemented. Industries began to work in close coordination with the state apparatus. Business hierarchies were adapted to the logic of military production. Technical commissions were created. The use of raw materials was optimized. and duplication in weapons design was eliminated.

Spear established regional armaments offices supervised by his personal representatives which allowed for rapid decisions without interference from traditional bureaucrats. Statistics began to show a notable increase in the production of tanks, aircraft, and munitions even under constant bombing.

Beginning in 1943, propaganda promoted the spear miracle as a demonstration of Germany’s ability to resist and respond effectively. The increase in production, however, could not be sustained by German labor alone. Total war demanded additional human resources.

The system increasingly resorted to the massive use of forced laborers, mostly from the occupied territories. These prisoners, whether civilians or deportes, were brought in by the millions to perform tasks in factories, mines, and infrastructure projects. Some were PS captured in previous campaigns. Others were civilians selected during raids in Poland, Ukraine, France, and other countries.

They were transported in precarious conditions, housed in barracks near industrial complexes, guarded by armed personnel, and subjected to grueling work days. The difference in treatment compared to German workers was stark. Punishments were frequent and control was exercised ruthlessly. The survival of these workers depended not only on their performance but also on the arbitrary conduct of their supervisors.

Despite the conditions, the regime justified their presence as a patriotic necessity, deliberately concealing the repressive dimension of the system. Within the country itself, the German population was also progressively absorbed by the logic of total war. The recruitment of men left large labor gaps that were filled by the massive entry of women into the industrial world.

While the regime had maintained a traditionalist discourse on the role of women, the pressure of the war forced it to soften that stance. Beginning in 1943, public campaigns were promoted to encourage women to participate in weapons production. Technical courses were offered, factories were adapted, and schedules compatible with domestic life were established.

Some production units installed cafeterias and daycare centers. This mobilization was presented as a joint effort for victory. Magazines illustrated women in work uniforms alongside tanks or airplanes. Although many conservative sectors were suspicious of these changes, the state machinery borked no opposition when it came to sustaining the war effort.

Control over civilian life became almost absolute with decisions about the fate of every citizen made directly from the Reich headquarters. Jobs were assigned according to production criteria and labor mobility was restricted to avoid regional imbalances. Since unions had disappeared before the conflict, there was no room for negotiation or protest.

It was the state that organized working conditions, set the workday, distributed rations, and authorized leave while factories remained active day and night under a a rotating shift system was justified by the need to achieve a common goal. This entire process was supported by the propaganda apparatus which spread the idea of a national community in arms presenting the worker as a combatant on the home front.

Radio stations broadcast reports on production progress and newspapers celebrated manufacturing figures as if they were military victories. In this context, any deviation from the collective effort was immediately denounced as sabotage or treason. The impact of this transformation was profound. Cities were filled with posters urging sacrifice.

Offices were reorganized to respond to strategic needs. Children were instructed in principles of productive discipline. Schools disseminated examples of technical effort and young people were sent to factories or farms as part of their patriotic training.

This was not just an economy serving the war effort but an entire culture of work under state control. This organization was presented as superior to the liberal one. Accused of being dispersed and chaotic, the German model, according to official rhetoric, demonstrated that discipline could transform even the most difficult times into moments of growth and order.

Albert Spear was portrayed as the symbol of this capacity. In his public appearances, he appeared with plans, graphs, and workers behind him discussing practical solutions. He did not wear a military uniform or use ideological language which increased his credibility as a technician in the service of the furer.

Hitler cited him as an example of the new generation of German leaders capable of combining efficiency and loyalty. This model of technical minister contrasted with traditional bureaucrats and reinforced the idea of a dynamic government adapted to the demands of the conflict. As time passed, however, the demands increased, stricter rationing systems were implemented, movement within the country was regulated, private celebrations were restricted, and leisure culture was subordinated to the culture of sacrifice.

Shows considered frivolous were banned. Cinema was required to exalt national resilience. And light music was replaced by patriotic marches and choirs. Churches, while maintaining their activities, were called upon to support the collective effort with messages of unity and commitment. The system left no gaps. Every sphere of life was to serve the same objective, sustaining the war at any cost.

The intensive use of forced labor and the total mobilization of internal resources allowed the German economy to maintain its level of production even when the course of the war turned adverse. This paradox was used by propaganda as proof that the nation remained strong. Suffering was portrayed as inevitable but heroic. The idea of resistance replaced that of quick victory.

Technical figures were more important than territorial conquests. And the Reich was portrayed as a great cohesive machine. Arms production reached record levels and that was enough to affirm that the cause was still alive. The narrative changed, but control intensified. Every German inside or outside a factory had to assume their role without hesitation.

Thus, total war transformed the Reich not only in its economy, but in its entire social fabric. Stalingrad, the loss of the Sixth Army, and the collapse of German morale. The defeat at Stalingrad, confirmed in January 1943, marked a dividing line between before and after the war for Germany.

It was not only a catastrophic military loss, but also a profound emotional breakdown both within the army and in the general mood of the people. The weeks that followed were marked by a silence that was unusual in official discourse. War reports no longer spoke of victories and the word Stalinrad was slow to appear on the lips of highranking officials.

The retreat that began at that point was not only territorial but also psychological penetrating all levels of the state apparatus and the civilian population population who for the first time began to look to the future with a mixture of fear and resignation. Perceptions within the army changed rapidly. Until then, many officers had trusted in Germany’s ability to resolve difficult situations.

But with the surrender of the Sixth Army, that confidence collapsed. Internal command reports began to show signs of disorientation. There was concern about the enemy’s ability to react, the mounting pressure on other fronts, and the impossibility of maintaining a sustained initiative.

Communications between commanders revealed a loss of confidence in the central strategy. Some even began to question high command decisions that until then had not been publicly questioned. What had previously been perceived as a complicated but manageable campaign transformed into a chain of defensive movements with little room for control. In the rear, signs of retreat gradually became more visible.

Evacuation orders from occupied territories, the restructuring of battered units, and the lack of sufficient reinforcements began to generate a shift in the narrative. Images of German columns retreating along muddy roads, often without air cover, became familiar sights. Soldiers were no longer seen as conquerors, but as survivors doing their best to stay on their feet.

Casualties mounted, and with them, so did the pressure on middle level commanders who had to respond to situations for which they were unprepared. The German initiative had evaporated and the adversary now dictated the pace of events. At the level of political leadership, the impact of Stalinrad was devastating.

The absolute confidence Hitler projected began to erode. While in public he maintained his unwavering rhetoric, in private he became more irritable, more distrustful, and less receptive to outside opinions. The command structure became even more rigid. Suggestions were rejected, losses minimized, and one’s own capabilities exaggerated. Some generals noticed that the decision-making center no longer responded to realistic assessments, but to a distorted view of the situation. Meetings became tense, and mentioning critical aspects was avoided for fear of

being overruled. Meanwhile, the propaganda apparatus continued to try to present an appearance of firmness, but the cracks were already all too evident, even within the most loyal circles. Official propaganda initially attempted to cover up the disaster.

There was talk of heroic sacrifices, of defense to the last man, of unwavering loyalty to the furer. But as the days passed, the prisoners accounts and foreign news arriving through uncontrolled means made it impossible to maintain the veil. Foreign shortwave stations gained listeners. Families who had received no news of their sons missing at the front began to fear the worst.

Rumors about what had happened in Stalingrad grew uncontrollably and many no longer trusted the official figures. In factories and neighborhoods, the name of the Russian city became synonymous with catastrophe. It was the first time that the word defeat began to take shape in the minds of the German people. Civil society experienced a shift in its perception of the conflict. Years before, victory speeches had been followed with enthusiasm.

Now they were greeted with skepticism. Lines at stores lengthened. Mail arrived late and anxiety became increasingly palpable. Conversations changed tone. Some still repeated official statements, but many began to speak in low voices about a possible unfavorable outcome.

Censorship was still in place, but in private spaces, talk was already spreading that the war could be lost. Some remained confident that there would be a sudden turn. Others, more realistic, began to mentally prepare for what seemed inevitable. In this context, expressions of passive resistance emerged. These were not organized gestures, nor were they articulated political movements.

Rather, they were individual reactions, a lack of enthusiasm for work, disinterest in official campaigns, and avoidance of public discourse. Pressure from their peers remained, but more and more people were looking for a way to express their discontent without exposing themselves to direct reprisals. The military retreat combined with a growing loss of confidence in the leadership.

It was perceived that decisions no longer responded to rational criteria, but rather to the stubbornness of a leadership disconnected from reality. Attempts to boost morale through speeches, awards, and parades were proving increasingly ineffective. Even some party officials privately acknowledged that the initial spirit had faded. Promises of quick victory were no longer convincing.

And the question that began to hang in the air was how to resist, not how to win. Officers at the front, like workers in the rear, felt the strain. The energy that had characterized the early years transformed into a mixture of exhaustion, resignation, and fear. In this context, German society underwent a silent transformation.

There was no open rupture or mass outburst, but there was a profound change in the way daily life was lived. Obedience became more mechanical, expressions of enthusiasm more forced, and following orders more automatic. People continued to fulfill their duties, but without the same conviction as before. Berlin in flames, the brutal end of the war for Germany. As the war turned sharply against Germany, cities began to feel the brunt of Allied air raids.

more strongly, which from 1943 onward became increasingly frequent, intense, and devastating. Nights ceased to be moments of rest and became moments of constant anguish with sirens wailing incessantly, shelters filled with entire families and explosions shaking everything in their path. By dawn, the streets were unrecognizable. Where there had been buildings, only smoking ruins remained.

Businesses were reduced to rubble, and homes were turned into craters. Human losses numbered in the thousands. Services collapsed. Water and electricity supplies disappeared. Food became scarce. And fear became a permanent presence. It was no longer just a matter of material destruction, but a blow.

Continued to the morale of a population that was beginning to accept that defeat was not only possible, but inevitable and increasingly close. Meanwhile, the regime attempted to maintain control through increasingly desperate measures, organizing the Folkm, a defense force composed of men either too old or too young for regular service, who received hasty training, outdated weapons, and impossible missions in the face of a determinately advancing enemy.

On the streets, teenagers in makeshift uniforms, elderly people armed with sharpened canes, and women no longer solely responsible for the home, but also for civil defense duties were seen. Schools closed to function as logistical centers.

Squares were transformed into arms and food distribution points, and instructions changed constantly as each neighborhood tried to resist with what little it had. Propaganda continued to repeat the promise of ultimate victory. But the majority of the population no longer believed these messages. The official language spoke of counter offensives. Although what they experienced was a succession of retreats, destruction, and deaths.

The arrival of the Red Army from the east was feared as the prelude to the final collapse, and the news circulating spoke of raised villages, brutal reprisals, and unbridled revenge. In Berlin, the Soviet cannons could be heard clearly as the bombing intensified relentlessly and the capital, which for years had been a symbol of power and pride, was transformed into a besieged city with no escape route.

The streets were filled with makeshift trenches. Buildings became half-ruuined fortresses, and underground shelters became shared graves. While the population tried to survive, not knowing whether to fear the shells, the crossfire, or their own commanders, who continued to ruthlessly execute those they considered cowards or saboturs.

The end of the regime came without speeches or ceremony, like a final decision made in an underground bunker. While everything was crumbling above ground, the news spread amidst the chaos without details or official confirmation, and it provoked neither surprise nor shock, but rather an absolute silence that for many was simply the realization that everything was over.

There were no longer any coherent command structures, no plan, no possible direction, and the only thing that remained was a feeling of emptiness in the face of the inevitable. The surrender was signed a few days later as the last pockets of resistance fell and the remaining soldiers laid down their weapons. Thus ended the war for Germany.

What remained was a country reduced to ruins. Cities were piles of rubble. Communications were cut off. Factories destroyed and families scattered. Survivors wandered among the wreckage looking for something to eat, something to drink, or simply someone they recognized. Hospitals were overwhelmed. Schools were closed.

There was no transportation or services, only smoke in the air, silence in the streets, and bodies abandoned everywhere. The state had ceased to exist. Authority no longer operated, and each person tried to hold on to what little they had left, with no time to reflect, barely able to stay alive for another day.

News

“Where do you think you’re going?! Your guests have arrived!” the mother-in-law exclaimed—only to get exactly the answer she deserved.

Anna carefully parted the curtain and looked out the window. The familiar white Logan pulled up to the gate, and…

The husband left for a younger woman, leaving his wife with enormous debts. A year later, he saw her behind the wheel of a car that cost as much as his entire company.

“I’d leave you the keys, but there’s no point.” Elena slowly raised her head. Andrey was standing in the doorway,…

CH1 Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

four hundred planes vanished 400 aircraft launched into the Pacific sky only a handful returned what happened on June 19th,…

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

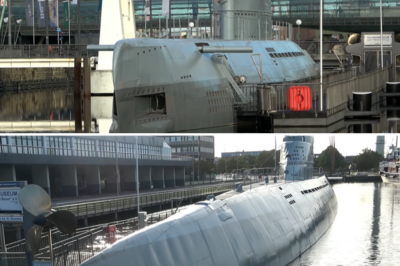

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

CH1 The Grueling Life of a WWII German U-Boat Crew Member

british prime minister winston churchill famously remarked after the war that the u-boat was the only thing that truly scared…

End of content

No more pages to load