Reckland, Germany. Winter 1943. The hanger smelled of oil, tobacco, and victory. Around a long drafting table covered in blueprints, four Luftvafa engineers leaned over a new intelligence file marked US Army Air Force’s engine type 1,650. One of them, Oberinganir Fran Müller, adjusted his wire rim glasses and laughed.

Packard Motor Company, he said, reading the stamped logo on the photograph. The Americans have copied the Merlin. They build luxury cars, and now they think they can build a Rolls-Royce. The others joined in a chorus of quiet arrogance. Outside the cold wind howled across the airfield, rattling the sheet metal walls, but inside the warmth of self asssurance filled the room.

To the Germans, engines were sacred. Perfection was not assembled. It was crafted. Every bolt on a Dameler Benb DB 6005 bore the signature of a man who had filed it by hand adjusted it by ear measured its balance with fingertips. To them, precision lived in the fingers of craftsmen not in the rhythm of a machine.

The Packard name known for American cars driven by businessmen and movie stars sounded to them like a punchline, not a threat. Mueller turned another page. The intelligence summary was blunt. The United States intends to produce 5000 Rolls-Royce Merlin engines under license for use in fighter aircraft. He exhaled through his nose.

They cannot even produce enough mechanics to maintain them, and they expect to build 50,000. Behind him, his assistant, Carl, flicked ash from his cigarette and replied, “Mass production kills precision.” It was a phrase repeated so often in German engineering circles that it had become doctrine. Every Spitfire they had examined carried a Merlin that sang with subtle imperfection.

Each cylinder tuned by ear, each valve spring slightly different. It was a living engine made by craftsmen who worked by feel. How could a machine shop in Detroit reproduce that? They remembered the reports from North Africa and the channel. American aircraft were heavy crude and loud. Their bombers bled fuel. Their engines leaked oil. Their mechanics used hammers where German engineers used micrometers.

The Germans respected the Americans for their resources, not for their refinement. They build in tons, not in tolerances, Müller said. He tapped the paper with a pencil. This is what happens when you let accountants build engines. The room erupted again in laughter, but the report contained something they could not ignore.

The Americans had taken the British blueprints and redrawn them entirely using their own standards. Every thread, every gasket, every bearing converted into a different measurement system. To the Germans, that was insanity. They will ruin it, Carl muttered. Convert millimeters to inches, destroy the clearances, melt pistons, seize bearings. Müller nodded in agreement. They will copy the form, not the function.

He wrote in the margin, “Copy equal sign inferior by design.” Outside, the sound of a messes starting up echoed through the airfield. The DB 6005 roared alive with that distinctive mechanical snarl, a sound every German pilot trusted more than his own heartbeat. Mueller turned toward the noise and smiled.

You see, that’s how an engine should sound, handbuilt, alive, pure. He closed the American file and snapped the leather strap across it. If they ever face us with these Packard toys, we’ll burn them from the sky. What Müller didn’t know was that across the Atlantic in a massive brick factory beside the Detroit River, those so-called toys were already running smoothly, endlessly, identically. He couldn’t imagine an engine that didn’t need a craftsman to make it sing.

He couldn’t imagine an assembly line capable of harmony. In Germany, perfection was art. In America, perfection was arithmetic. That night, Müller recorded his thoughts in his log book. American arrogance continues. He wrote, “They believe machines can replace men. They believe quantity can replace quality. They may have factories, but we have engineers.” He underlined the last sentence twice.

Years later, when historians found that notebook, the ink had faded, but the irony had not. The men who believed machines could never equal their craftsmanship were about to be defeated by machines that produced perfection by the thousands. But in 1943, they couldn’t see it. They saw only the blueprints of a copy and laughed.

If you believe those engineers were right that mass production destroys quality hitlike. But if you think they were wrong, that true genius lies in building precision for everyone. Not just for the few comment the number seven Derby England early 1940. The war had barely begun, but inside the brick walls of the Rolls-Royce factory, it already sounded like eternity.

Hammers sang against aluminum micrometers, clicked in measured rhythm, and the air shimmerred with the heat of labor. The Merlin engine, 12 cylinders of British defiance, was being born one breath, one heartbeat at a time. To those who built it, the Merlin was not machinery. It was music made of metal. In the assembly bay, a craftsman named Harold Watkins stood over a half-finish crankcase.

He’d been with Rolls-Royce since the 30s, long before the word war filled the newspapers. His fingers calloused from a lifetime of filing metal moved like a surgeons. Every stroke of the file was a conversation between man and material. He whispered numbers as he worked thousandths of an inch degrees of alignment moments of balance. The gauge read 0.00005.

He smiled. Perfect. The Merlin was not designed for mass production. It was designed for immortality. At 27 L, it weighed 1640 lb and produced 1,500 horsepower at full throttle. An orchestra of pistons, valves, and gears spinning in perfect harmony. Each engine consumed more than a,000 man-h hours of labor.

Every component came with its own quirks and secrets, slight variances in the alloy, subtle differences in the machining. Rolls-Royce engineers didn’t fight those imperfections. They tuned them like a violin maker adjusting strings by ear. When the first Spitfire took flight with a Merlin under its cowl, Britain discovered that sound could carry courage.

Pilots said they could feel the engine breathe with them, respond like a living creature. At full boost, the propeller blurred to invisibility, the cockpit trembling with the pulse of 12 pistons firing 150 times per second. The engine’s growl became the anthem of survival during the Battle of Britain.

In pubs across London, men would swear that the Merlin’s hum could be heard miles away, a metallic heartbeat, promising that the island still lived. Rolls-Royce guarded its masterpiece like a secret religion. In the design offices, blueprints were handdrawn in black ink on linen paper, each marked property of his majesty’s government. To change even one tolerance required approval from a board of senior engineers.

When a new apprentice asked why no two engines seemed identical, his mentor replied, “Because they are not made by machines. They are made by men.” News of the Merlin success spread quickly, even to enemy intelligence. The Germans called it the Spitfire engine, the heart of the plane that turned their daylight raids into burning wrecks.

But while they studied its performance with grudging respect, they still dismissed its production as quaint. Rolls-Royce could build brilliance, but not abundance. Every Merlin demanded the hands of master craftsmen. Every aircraft required months of waiting. The Germans had already built thousands of messes powered by the DB6001 and DB6005 engines that rolled off assembly lines in numbers Britain could never match.

By 1941, that arithmetic had become deadly. British factories were working 20-our days, yet fighter output barely kept pace with losses. Every engine was precious. When one failed, a pilot’s life often ended in fire. In derby, mechanics wept when a damaged Merlin returned to the hangar.

They would touch the scorched metal like mourners at a funeral, whispering, “She tried her best.” The Merlin was more than machinery. It was personality loyalty sacrifice. And that devotion was both its strength and its curse. Across the Atlantic, American observers tooured the factory notebooks in hand, eyes wide with disbelief. To them, this was genius.

trapped in amber hand fitted valves, custom ground cams, variations so subtle that no two engines could swap parts. One American engineer from Packard reportedly asked, “How do you expect to win a war building engines like violins?” The Rolls-Royce foreman answered quietly, “Because ours play the right tune.” That answer summed up the British philosophy of engineering craftsmanship as patriotism, precision as poetry.

But poetry could not fill the skies fast enough. By 1942, the Royal Air Force was begging for thousands of engines it couldn’t yet build. And that desperation led to an idea almost no one in Derby wanted to accept handing the Merlin’s blueprints to America. When word reached the shop floor that Packard Motor Company in Detroit would begin manufacturing Merlin under license, many workers felt insulted. One machinist slammed his wrench on the bench and muttered, “They’ll ruin it.

Americans make cars, not engines fit for heaven.” Another replied, “They’ll drown it in oil and call it progress.” Even some executives doubted it could be done. Rolls-Royce engineers measured tolerances in fractions of human hair. Packard measured in fractions of minutes. But war has a way of forcing humility.

The Spitfire and the Lancaster could not wait for pride. The United States had factories larger than entire English towns, and their machines could stamp, mill, and grind faster than any human hand. The only question was whether speed could coexist with soul. By the summer of 1942, wooden crates filled with drawings left Derby for Detroit and 21,000 blueprints, each one, a fragment of British genius crossing an ocean.

The craftsmen watched them go half proud, half afraid. They didn’t yet know that in a matter of months the Americans would return those blueprints transformed not by art but by arithmetic. If you believe a masterpiece loses its soul when it leaves the hands of its maker pressike. But if you believe that true genius can survive translation, that art can become industry without losing beauty.

Comment the number seven. Detroit, Michigan, autumn 1942. The night sky glowed orange above the Packard Motorcar Company, not from bombs or fire, but from the furnace of creation. The factory ran 24 hours a day, its brick walls vibrating with the pulse of war.

Inside the sound was constant steel stamping, rivet guns, hammering engines roaring on test stands. America had entered the war, and Detroit had become the heart of its mechanical army. Packard had been known for luxury automobiles, smooth engines, polished wood dashboards, silent rides for the wealthy. But when the government called the company answered, the United States had promised Britain not just weapons, but miracles in quantity.

They needed to mass-produce the Rolls-Royce Merlin, the most advanced aircraft engine in the world. And they needed to do it at American speed. At first, even Packard’s engineers hesitated. The blueprints that arrived from Derby were a riddle written in another language.

Measurements in fractions, tolerances in decimals, threads in Witworth instead of SAE. Rolls-Royce drawings were elegant but chaotic handwritten notes, secret symbols known only to the draftsman who made them. Packard’s lead engineer, Jesse Vincent, stared at the mountain of paper and said quietly, “If we build this the British way, we’ll build one engine a month. We need to build one every hour.

The challenge was not just technical. It was philosophical. Rolls-Royce believed in perfection through craftsmanship. Packard believed in perfection through process. In Britain, a single craftsman adjusted every valve by hand. In Detroit, machines did not trust feelings. They trusted gauges. So, Packard redrrew every blueprint from scratch.

21,000 in total translated from artistry into mathematics. where Rolls-Royce wrote fit snug, Packard wrote clearance 0.0012 plus 0.00001 in. For months, engineers labored without rest. They standardized threads, bearings, and fittings so that every part could fit every engine. They designed jigs that held components so precisely that human error vanished from the equation.

They built calibration tools that measured tolerances finer than the width of a red blood cell. And then they began the most ambitious industrial experiment of the war to build genius by assembly line. In one vast hall, rows of women in coveralls worked under the glare of mercury lamps. Each specialized in a single operation, grinding, honing, inspecting, torquing each movement timed to seconds.

A supervisor carried a stopwatch and a clipboard. The clang of wrenches formed a rhythm mechanical yet strangely human. When an engine block reached the end of the line, another worker slid in its place. There was no silence, no pause, no delay. To observers, it was overwhelming.

A visitor from the British Air Ministry wrote in his report, “It is like watching an orchestra where every instrument is made of steel, the engines gleamed under fluorescent lights. Aluminum brass steel born not from hands but from precision tools. Each component identical to the one before it. Interchangeable, replaceable, perfect by repetition.

But not everyone believed it would work. British advisers doubted that mass production could match their handcrafted tolerances. One senior Rolls-Royce engineer muttered, “They’ll build fast, yes, but they’ll build wrong.” Jesse Vincent disagreed. He told his team, “We’re not just building engines.

We’re building a new kind of perfection, one that anyone anywhere can repeat. Packard introduced quality control procedures that had never existed in British plants. Every part passed through three separate inspections. Every measurement was logged in decimal precision. Workers were trained not to adjust by instinct, but to trust instruments. In Derby, that would have been heresy.

In Detroit, it was progress. By December 1942, the first prototype designated the V1,651 sat on a dynamometer stand. When the ignition switch turned, the engine came alive with a sound no one expected, smooth, even steady. The vibration that had haunted the early British Merlin was gone. At full throttle, the Packard engine purred like it had been carved from a single block of metal.

Reporters were invited to witness the first test run. In the observation room, a British attache whispered, “It runs smoother than ours.” He meant it as disbelief, not praise. But the data confirmed it. The Packard Merlin delivered the same power with lower fuel consumption, fewer leaks, and longer life.

Its clearances were so uniform that bearings could be swapped between engines without a single adjustment. Detroit had done what no one thought possible. It had turned the most complex handmade engine all on earth into an industrial product. Within 6 months, Packard could build a Merlin every 60 minutes.

Each engine cost less, lasted longer, and required fewer mechanics to service. Precision had been democratized. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, British factories watched in astonishment as the first Americanbuilt Merlin arrived. They fit perfectly into Spitfires and mosquitoes bolted on without modification. Pilots reported the same thrust, the same sound, but fewer failures.

Rolls-Royce engineers examined the engines in silence. The parts bore strange markings, Packard serial numbers, American fonts, but they were flawless. When the first Packard Merlin reached North American aviation, they were mounted on a new airframe called the P-51 Mustang. The combination was alchemy.

With the Merlin’s high alitude supercharger, the Mustang leapt to 437 mph, outrunning and outclimbing anything Germany could send against it. What began as a copy had become a legend. Inside the Packard plant, Jesse Vincent walked the line as hundreds of engines thundered on test stands. He turned to his foreman and said, “You hear that? That’s what victory sounds like.” The foreman nodded. It sounds like Detroit.

In Reclan, the German engineers who had once mocked the American license now received new intelligence reports. They read that American factories were producing 500 Merlands a week. Mulleller, the same engineer who had laughed over the blueprints, stared at the figures in disbelief. 50,000 engines, he whispered. They build them like toys. But these toys would soon fill the skies over Europe.

Across oceans, across languages, a new philosophy had emerged. In Britain, craftsmanship had created brilliance. In America, standardization had made it unstoppable. The Packard Merlin was no longer an imitation. It was evolution by mathematics. If you believe perfection belongs only to human hands, presslike. But if you believe perfection can be multiplied, shared, and built by thousands of ordinary people working in harmony. Comment the number seven. Dearbornne, Michigan, January 1943.

The snow outside was silent, but inside the Packard test facility, the air trembled. Dozens of engineers stood behind thick glass windows, staring at the dynamometer bay. A single Merlin engine gleaming chrome bright, every bolt engraved with Packard Motor Division, Detroit, USA, sat chained to its test stand like a caged animal. On the control board, red lights flickered.

The operator raised his hand. Contact, he said. The ignition key turned. The first cough of combustion cracked the silence. Then a roar, clean, steady, perfect. The 12 cylinders came alive not with the rasping snarl of a British test stand, but with a deep balanced hum that filled the building like an organ. For the first 20 seconds, no one spoke.

Then Jesse Vincent exhaled the tension breaking she runs. But running was not enough. The test had to prove more than motion. This engine would be pushed to 500 horsepower at 3000 revolutions per minute for 150 consecutive hours without a single seizure leak or failure.

It was a trial Rolls-Royce had never dared to attempt. If Packard’s copy survived, it would silence every doubt on two continents. Hour after hour, the engine thundered. Technicians rotated in shifts, measuring vibration oil temperature bearing clearances. At 30 hours, the British observers began to relax. At 70 hours, one of them muttered, “It’ll quit soon.” They all do. At 120 hours, they stopped guessing.

And at 150 hours, when the engine shut down, it was still within 1% of its original performance. The numbers were undeniable power output, stable compression, perfect fuel efficiency, higher than any previous Merlin. Jesse Vincent turned to the visiting Rolls-Royce liaison and said softly, “You still think we can’t mass-produce art.

” The man hesitated, then smiled in disbelief. “I think you just did.” The results crossed the Atlantic in coated cables. At Derby, the message landed like thunder. Packard test successful. Engine passed 150 hours full power. No defects. For a moment, the factory floor fell silent. Some men were proud. Others were ashamed.

One senior designer said, “They have taken our genius and made it reproducible.” Another simply nodded and whispered, “Good. Then maybe we’ll win this war.” By spring 1943, Packard was shipping hundreds of engines a month. Each one identical, interchangeable, serialized.

Mechanics in England could swap parts between aircraft without adjustment. Pilots noticed the difference immediately. The Americanbuilt Merlin started cleaner, ran cooler, and climbed higher. They were less temperamental, more obedient. They had lost the romance of the handbuilt engine, but gained something more valuable, reliability. The true test came when North American aviation installed the Packard Merlin into the P-51 Mustang.

On April 30th, 1943, the prototype roared down the runway at Englewood, California. Test pilot Bob Chilton pulled back the stick and the silver aircraft leapt into the air. The combination was electrifying. The Merlin’s Supercharger sang as the Mustang climbed past 3000 ft in minutes. At 2500 feet, the air thinned, but the engine didn’t falter. At 3500 0, it still pulled hard.

Chilton radioed ground control, laughing through the oxygen mask. Gentlemen, I think we just changed the war. Within months, the new P-51B entered service. It was fast, long-legged, deadly. It could escort bombers deep into Germany, a strike at targets no Allied fighter had ever reached, and still have the fuel to come home.

German pilots who once mocked American planes as clumsy and overweight now faced opponents that were higher, faster, and seemingly endless. The Luftvafa had entered an unwininnable race against numbers and altitude. In July 1943 near Otter Bremen, a formation of B17 bombers flew under P-51 escort for the first time. From the ground, German spotters reported new aircraft unknown type very high alitude extreme speed.

When the first messes climbed to intercept, they found themselves already under attack. One German pilot overlit Carl Hines Moritz later described the encounter. They came out of the sun. I thought they were Spitfires, but they kept climbing higher than any Spitfire ever could. I hit full throttle. They were still above me.

Then the tracers came down like lightning. After the battle fragments of a crashed P-51 were recovered by German engineers, they pried open the cowling, expecting to find the familiar British stamp. Instead, the words on the data plate stunned them. Packard Motor Division, Detroit, USA. The same city that once built limousines was now building death from the sky.

One engineer ran his hand over the smooth casting of the cylinder head and muttered, “They have improved it. Damn them, they’ve improved it.” By late 1943, the Packard Merlin had become the beating heart of Allied air power. Not only Mustangs, but also Mosquitoes and Lancasters flew with Americanbuilt engines. The statistics were brutal.

Mission range increased by 60%, escort losses dropped by half and operational readiness climbed above 90%. The Luftvafa’s nightmare wasn’t just the aircraft. It was the endless supply of engines that kept coming. In Germany, reports piled up on the desk of General Feld Marshall Hehard Mil. Intelligence estimated that American factories were producing Merlin faster than the Luftvafa could destroy them.

Milch underlined one sentence in red pencil. Enemy industrial capacity now beyond measurable limits. He looked up and said to his aid, “They have turned engineering into warfare.” Meanwhile, in Detroit, the factory lights never dimmed. Welders worked under the rhythmic glare of sparks. Inspectors checked gauges against master templates.

Women on the assembly lines wore badges marked Merlin Division. Every six minutes, a new engine rolled off the line. When a visiting journalist asked a foreman what kept them going, he pointed to a wall of photographs pilot standing beside Mustangs and said, “Every picture is one we keep alive. The transformation was complete.

The same American industry that once built luxury cars for peace now built precision for survival.” The Packard Merlin had begun as a copy dismissed by its enemies, doubted by its allies, and born under pressure. But it ended as proof that America’s greatest weapon was not steel or speed. It was system. Across the ocean, the German engineers, who had laughed over the blueprints a year earlier, now read reports of P-51s tearing through bomber formations at 3000 ft.

Müller, the man who once wrote copy equals sign inferior by design, tore the page from his notebook. He couldn’t bring himself to burn it. He only stared at the torn paper and whispered, “It seems we were the copy all along.” “If you believe real genius is measured not by how something is built, but by how many lives it can save,” comment the number seven.

If you think perfection dies the moment it leaves the craftsman’s hands presslike. Either way, history has already answered. Reclan Airfield, Germany, December 1943. The morning fog hung low, thick enough to swallow the sound of distant engines. In a hanger lit by dim bulbs, a group of Luftvafa engineers stood around the twisted wreck of an aircraft they had never seen before.

Its fuselage was silver, its wings long and thin, the skin smooth as glass. The nose had been sheared open by impact, revealing the heart of the machine, an engine so cleanly machined so symmetrical that for a moment no one spoke. Obering France Müller, the same man who had once laughed at the idea of an Americanbuilt Merlin, crouched near the wreckage.

The metal still held the faint smell of oil and burned glycol. On the fractured data plate, the words were still legible. Packard Motor Division, Detroit, USA. He touched the engraving with a gloved finger. His voice was quiet. So this is it, he murmured, the copy. They began disassembling the engine in silence. Tools clicked and clattered against aluminum.

When the first cylinder head came off, they froze. Every surface was mirror smooth. The tolerances exact the machining flawless. Carl, his assistant, bent closer and ran a caliper across a bearing journal. Two microns difference, he whispered. That’s impossible. Ours vary by 20. Muller nodded slowly. They don’t build engines, he said.

They build measurements. He lifted a connecting rod and stared at it like an artifact. Rolls-Royce shaped this by hand, he said. But these, he held it under the lamp. These were born identical. Each one perfect, each one the same. On the wall behind them, a chalkboard filled with earlier intelligence report still bore the words P-51 Mustang New Allied Fighter.

They had underestimated it, assuming it to be another short-range interceptor. But now the wreckage told a different story. The Merlin engine reborn in America had given it the reach to escort bombers all the way to Berlin and back. The war in the air was no longer about tactics. It was about endurance.

Later that afternoon, they gathered in the observation bunker to review combat footage recovered from forward units. The projector flickered to life showing German gun camera film from a Faula Wolf 190. In the grainy black and white frames, a silver aircraft dived from above, too fast to track. Tracers arked upward, missing wildly. Then, in the next second, the Mustang opened fire. A clean, bright burst of light, and the film ended in smoke. “Impossible,” one officer said.

“No piston engine climbs like that.” Mueller shook his head. It’s the supercharger. Two stages, two speeds. At altitude, it breathes as if it were on the ground. He pointed at the data from recovered wrecks. They solved cooling. They solved pressure. They solved everything. A mechanic entered carrying a small box.

Inside were fragments of ball bearings recovered from the engine. Still round, the man said after the crash. Müller examined one under a magnifying lens. The bearing surfaces were polished to perfection. They didn’t polish these by hand, he said. They polished them by mathematics.

The mood in the hangar shifted from curiosity to disbelief, then to something quieter respect. The men who had mocked Detroit now understood what they were facing. Packard hadn’t just copied Rolls-Royce. They had created an engine that could be built faster, run longer, and survive where precision once depended on luck. Word spread quickly through Luftwafa circles.

Pilots began reporting the new American fighter long range high altitude near unstoppable. They called it Durilburn Younger the Silver Hunter. It appeared without warning, dived like lightning, and vanished before radar could track it. One ace described it in his diary. It comes from above, silent until it fires. The tracers arrive first, then the roar. You feel like you’ve been hunted by mathematics.

By early 1944, intelligence briefings included detailed comparisons between the German DB 6005 and the American Packard Merlin. The DB6005 was lighter and more compact, but required constant maintenance, exact fuel, and careful handling. The Merlin could run dirty overheat, cool itself, and keep going. One report concluded bitterly, “Our engines are raceh horses.

Theirs are machines built to win wars. When the first captured P-51s arrived intact after forced landings in occupied France, engineers finally had a full specimen to study. They rolled it into the test bay, washed the mud from its wings, and removed the cowling. The craftsmanship was so clean it looked surgical.

Even the wiring looms were labeled and colorcoded, a sign of design for the unbreakable, not the beautiful. Carl handed Müller a typed summary of test results. He read it twice, then set it down. Superior oil pressure stability, superior temperature control, superior material fatigue, identical compression across all cylinders.

He paused, then added quietly. They have done what we thought only a craftsman could do. That night, Müller returned to his quarters and opened his old log book, the one that still contained his note from 1942. copy equal sign inferior by design. He stared at the line for a long time, then crossed it out with a single stroke of his pencil.

Below it, he wrote, “Perfection is not an accident. It is a system.” Outside the distant rumble of bombers rolled across the horizon, the sound of American industry at work. The sky itself had become a production line, endless, mechanical, unstoppable. For the first time, Müller felt something he had never felt before in his career as an engineer. Awe.

In the weeks that followed, reports of P-51s escorting bombers to Leipig Munich in Berlin became daily routine. Luftvafa losses climbed. Pilots returned to base shaken, describing endless swarms of silver fighters. They never run out of engines. One said, “We shoot one down, two take its place.” Back in Rashlin, the engineers stopped laughing. They no longer spoke of art or genius.

They spoke of ratios, torque curves, and standard deviations. They began copying the very techniques they had once ridiculed. Precision by procedure, not pride. But it was too late. America had mastered the geometry of war. One night, as he left the hangar, Müller paused to look back at the shattered Mustang they had dissected. The moonlight glinted off the broken engine casing.

He whispered almost to himself, “They built their perfection for everyone. We built ours for the few. That’s why they will win.” If you believe that true power comes from the few who create pressike, but if you believe victory belongs to those who share perfection until it becomes unbreakable, comment the number seven.

By the spring of 1944, the war had become a contest of engines as much as of men. In the air above Europe, thousands of machines screamed the same metallic chorus. One side built for precision, the other for quantity. Yet the difference between those two ideas had become the line between victory and extinction. The Germans had built masterpieces. The Americans had built a method.

Inside the Reclan Technical Institute, the engineers gathered one last time to compare their numbers. Charts, graphs, and oil stained reports covered the table. The German DB 6005 engine, once the pride of the Luftwaffa, could deliver 1475 horsepower, but required 35 hours of maintenance for every 10 hours of flight.

The Packard Merlin produced nearly the same power, yet demanded only 5 hours of maintenance for every 50 flown. The statistics were brutal. Packard’s factory could produce five Merlin in the time it took Dameler Benz to hand assemble one. Rolls-Royce had built 20,000 Merlin since 1939. Packard alone would produce 55,000 before the war ended. To German engineers, those figures were more devastating than any bombing raid.

Their culture of craftsmanship, centuries of pride in the hands of masters was being outpaced by a philosophy that worshiped replication. It was no longer about genius, but geometry. Müller studied the data with the weariness of a man who had seen his beliefs dismantled bolt by bolt. He whispered, “They have made perfection common, and that is the highest form of genius.

” Across the ocean in Detroit, that same philosophy roared to life every minute of every day. The Packard plant operated in shifts so continuous that the machines never cooled. Assembly lines moved like arteries pumping hot steel. Precision gauges hung from every station, calibrated to tolerances finer than anything used in Europe. To the untrained eye, the place looked chaotic.

Sparks, flying cranes, swinging pistons rattling. But the chaos was organized. Every motion, every cut, every torque value had been calculated, rehearsed, repeated. Visitors described the plant as a living organism. The workers, men and women alike, became extensions of the machines they operated. Each person knew their task and nothing more. Yet together they formed an intelligence greater than any single engineer.

In the offices above the floor, Jesse Vincent would often stand by the window watching hundreds of engines take shape below. To him, this was America’s cathedral, the hum of creation powered by ordinary people who would never see the war, but would win it all the same. The numbers proved it.

Between 1943 and 1945, Packard delivered more than three 600 Merlin engines every month. Each one identical, each one tested each one ready for flight. The cost per engine fell by nearly 40% while reliability increased. The military called it production efficiency. Historians later called it industrial poetry. When the British liaison officers visited the Detroit plant for the final inspection, they stood in awe.

One of them, a veteran Rolls-Royce engineer, ran his hand along a row of completed engines and said quietly, “We used to sign our work. Now they all sign the same name.” It wasn’t cynicism. It was admiration. He realized that the soul of engineering had changed shape. The masterpiece was no longer a single creation, but the system that could make thousands of them identical.

In Germany, that revelation came too late. Their factories bombed and broken could no longer sustain the old way. Skilled craftsmen were irreplaceable, and there were too few left. Machines that required artistry were useless in a world where war demanded multiplication. The Luftvafa had built raceh horses. America had built tractors that could run forever.

Müller wrote in his final report, “The Americans have achieved what we considered impossible. They have standardized precision itself.” He paused, then added one more line. “In their hands, genius became infrastructure.” By the summer of 1944, the Allies owned the skies. The sound of the Merlin Packard’s Merlin was the sound of inevitability.

It filled the air over France, over Holland, over Germany itself. Each thundering formation was proof that philosophy could be as powerful as firepower. Even after the war, the lesson endured. When Rolls-Royce engineers visited Detroit in 1946 to study Packard’s methods, they found something unexpected. The Americans spoke not of pride, but of procedure.

We trust the process, one supervisor said. If the process is perfect, the product will be too. It was faith of a different kind, not in hands or intuition, but in data discipline and design. Years later, when interviewed about those days, Jesse Vincent was asked what the secret had been. He smiled and replied, “We stopped trying to build the best engine. We started trying to build every engine the same.

That’s how you win wars and how you build peace.” The story of the Packard Merlin was no longer about who invented what or whose genius came first. It had become a testament to an idea that would define the modern age that perfection once the privilege of a few could be reproduced by the many.

If you believe perfection dies when it is copied presslike, but if you believe perfection multiplies when it becomes a system, if you believe that power lies not in the master’s hand, but in the countless hands that repeat his art. Comment the number seven. Munich, West Germany. Autumn 1963. The war had been over for 18 years. Yet to France Müller, it still lived in the sound of an engine.

He was 62 now, retired half-deaf in one ear and slower with the tools that had once defined him. But when the invitation arrived from the Deutsches Museum, a new aviation exhibit featuring Allied aircraft, he could not resist. The letter said, “One would be a P-51D Mustang restored to flight condition.” He read the name twice. Packard Merlin.

On the day of the opening, the museum was crowded with students, families, and gay-haired veterans. Children ran under the wings of a Spitfire, and old men stared at the shattered fuselage of a messmitt as if it still whispered. Müller moved slowly, leaning on his cane until he saw it.

The Mustang, silver, polished to a mirror finish. The propeller blades glinted under the skylights like a halo. On its engine, cowling in black lettering, powered by Packard Motor Division, Detroit, USA. He stopped 5 m away and simply listened. A museum technician sat in the cockpit running pre-flight checks. The ignition switch clicked, the starter motor winded.

Then came the sound he remembered, the smooth, deep growl of 12 cylinders breathing in perfect sequence. The room filled with vibration, subtle but alive. The sound rolled through his chest, awakening something he thought he had buried forever. It was the same sound that had haunted him two decades earlier at Recklin.

The sound of precision without personality, the hum of a machine that had no need for genius. But now it felt different, softer, noble even. It wasn’t the sound of humiliation anymore. It was the sound of history forgiving itself. He closed his eyes and saw it all again. The torn wreckage on the hangar floor, the shining bearing. He couldn’t explain the young engineers staring in disbelief.

He had once hated that engine, not for what it was, but for what it proved, that his world, the world of craftsmen and perfectionists, had already ended before he realized it. When the engine shut down, Müller approached the aircraft. The technician, seeing the veteran’s cap on his head, smiled politely.

You worked on the German side, didn’t you? Müller nodded. Engines, he said. Always engines. The technician gestured to the Mustang. Beautiful, isn’t she? Müller studied the machine for a long moment. Yes, he said finally. Because she was not built to be beautiful. She was built to endure. He placed a hand on the cowling, feeling the cool metal under his palm.

He whispered, “You were never a copy.” That night, back in his small apartment, Müller opened an old leather notebook, the same one he had carried through the war. On its yellowed pages were equations, sketches, and fragments of reports.

Near the beginning, still legible in faded ink, was the line he had once written with such certainty, “Copy equals sign inferior by design.” He stared at it for a long time, then drew a line through it, firm and final. Below it, he wrote, “A copy made with understanding becomes an invention.” He paused, then added one last entry, his handwriting shaking slightly. “They built not from pride, but from purpose. They built for men they would never meet to fight battles they would never see.

Their machines carried the soul of a system that valued everyone. That was their genius.” He closed the notebook and looked out the window at the evening lights of Munich. The city had rebuilt itself the way Detroit once built engines. Brick by brick, process byprocess. The world had learned that survival belonged not to the most brilliant, but to the most adaptable.

Müller thought about the young engineers he had trained after the war boys who spoke of computers and automation instead of pistons and carburetors. They admired technology without worshiping it. Perhaps that was how it should be.

Perhaps the real lesson of the Packard Merlin wasn’t about engines at all, but about humility, that greatness endures when it stops needing credit. He turned off the lamp and sat in the darkness. From somewhere in the city, faint and distant, came the echo of an aircraft passing overhead. He imagined the sound not as defeat, but as continuity, the living heartbeat of an idea that outlived every flag, every nation, every war.

He whispered one final sentence into the quiet room. We built our masterpieces by hand. They built theirs by belief. If you believe genius belongs only to those who create it once pressike. But if you believe true genius lies in those who make it live forever, in every engine, every system, every hand that repeats perfection. Comment the number seven.

News

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

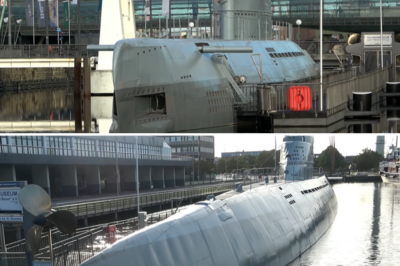

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

CH1 The Grueling Life of a WWII German U-Boat Crew Member

british prime minister winston churchill famously remarked after the war that the u-boat was the only thing that truly scared…

CH1 U-530: The U-Boat That Escaped to Argentina

At dawn on July 10th, 1945, Argentine fishermen off the naval base at Mardel Plata saw an unexpected silhouette emerge…

CH1 This Was the CHILLING LIFE of Germans Inside a SUBMARINE!

German submarines known as Yubot were a key part of national socialist naval strategy. They were small cramped vessels where…

CH1 What Happened When the 1st SS Met Patton’s Elite at the Bulge?

By the end of 1944, after a series of military defeats on both fronts, the Third Reich found itself on…

End of content

No more pages to load