German submarines known as Yubot were a key part of national socialist naval strategy. They were small cramped vessels where young sailors spent weeks underwater attacking enemy convoys. Commanders like Otto Cretchmer, Gaprin and Eric Top led these missions under very difficult conditions.

The routine on a yubot was brutally strict and exhausting. Watch shifts were divided into 4-hour cycles in an environment where personal space was non-existent, and the smells of oil, sweat, and rationed food permeated everything. They slept in shifts on warm beds shared by three or more sailors, ate canned or dehydrated food, and didn’t see sunlight for weeks.

How did German sailors live? How did they die? What remained of them and their machines after the war? That’s why today we’ll tell you about the brutal life inside Nazi submarines and what happened to them after the war. The abyssal strategy, the importance of German hubot in World War II. At the beginning of the 20th century, the naval world was still dominated by large battleships and surface cruisers.

However, a radical change was brewing in Germany’s shipyards, a submarine fleet designed not only to monitor, but to destroy from the depths. With the first world war, German submarines known as unaboot or simply yubot proved to be a strategic threat. But it was in World War II that they reached their most lethal form and greatest prominence.

When Adolf Hitler ordered the reactivation of German military power, the marine, the navy of the Third Reich, received clear instructions to build a modern, fast, discrete fleet capable of disrupting enemy maritime trade. Thus, the Yubot were reborn, led by Admiral Carl Donut, a veteran commander who fully understood the destructive potential of submarine warfare. Donuts had a clear vision.

He wanted to use yubot to implement the so-called war of attrition, also known as privateeering. The idea was simple. Sink merchant ships faster than the allies could build them. It wasn’t just about torpedoing military targets, but also cutting off vital supplies, especially those crossing the Atlantic to Great Britain. The plan worked, at least at first.

During the first years of the war, Ubot wre havoc. The most widely used models, such as the Type 7, became the true workh horses of the Atlantic. Fast, reliable, and relatively cheap to produce, these submarines had a range of over 8,000 km, could dive to 220 m deep, and were armed with lethal torpedoes capable of sinking freighters weighing tens of thousands of tons.

The first successes were not long in coming. In 1940 and 1941, the Ubot operated with almost ghostly effectiveness. They sailed at night, hid in the fog, struck undetected, and disappeared into the abyss without a trace. This period was known as the happy era for German submariners, as casualties were few, and the number of ships sunk grew week after week.

Entire convoys were devastated in the Mid-Atlantic with little the escorts could do. Tactics also evolved. Donuts introduced the wolfpack system or rud tactic, a strategy in which several hubot work together to attack a convoy from different points, saturating enemy defenses. This technique, although difficult to coordinate, had a devastating effect. The importance of the yubot was not only tactical but symbolic.

For the third Reich, every yubot returning to port was greeted as a hero. The crews were celebrated, decorated, and used in Nazi propaganda. Young Germans dreamed of becoming Yuboat officers, little imagining the brutality that lay beneath the surface. But while the Ubot were reaping successes, the Allies did not stand idly by. From 1942 onward, the tide began to turn.

The introduction of new technologies such as highfrequency radar, advanced sonar, and attacks from escort carriers drastically weakened the effectiveness of Ubot. Anti-ubmarine warfare evolved at breakneck speed. Convoys began to be better escorted. British intelligence managed to decipher German communication codes thanks to the Enigma machine, making it possible to anticipate the movements of Yubot flotillas.

Furthermore, aerial advances marked a turning point. Aircraft capable of long-d distanceance patrols began to cover the previously blind areas of the Atlantic, where hubot operated more freely. Within months, what had once been an advantage became a deadly hunting ground. The numbers are stark.

Of the nearly 1,150 Ubot that Germany built during the war, around 780 were destroyed. The mortality rate among crews exceeded 75%, making it one of the highest of any armed force during the conflict. Many submariners never returned. They sank silently without warning with barely seconds to react. Yet until the end of the conflict, Hitler insisted on keeping this submarine force active.

He even ordered the development of revolutionary models such as the Type 21, considered the first truly modern submarine capable of operating submerged for days without needing to surface thanks to its improved batteries and hydrodnamic design. This new type, although promising, arrived too late to change the course of the war.

The evolution of Yubot was not limited to models alone. Their missions also diversified. Some submarines were adapted to launch experimental missiles, others to transport spies or classified material. Yubot also operated in the Arctic, the Mediterranean, and even the Indian Ocean as part of tactical alliances with Japan.

In strategic terms, Yubot forced the Allies to divert vast resources to protecting their shipping lanes. Escort ships were built, detection networks were developed, air stations were expanded, and exclusion zones were established. All of this was an indirect victory for the Germans. While the Allies defended their supply lines, the Reich could concentrate part of its efforts on other fronts.

But despite their importance, the Ubot never managed to fulfill their primary objective, starving Britain into submission. The ships kept arriving. The flow of supplies continued, and the Americans, once they entered the war, exponentially multiplied naval production. Even so, the Yubot left an indelible mark on naval history.

They were the symbol of silent terror of the invisible threat and also the metallic tomb of tens of thousands of men who fought on a front without light, without fresh air, without escape. Nazi submarines not only changed the way war was waged at sea, they redefined what it means to survive under pressure in the most literal and human sense of the term.

Prepared to die, whats marine yuboat training was like. Boarding a German Ubot wasn’t simply a matter of putting on a uniform and setting sail into the Atlantic. It required extremely rigorous technical, physical, and mental training. The men who manned these steel tubes weren’t ordinary sailors, but an elite group trained to operate in silence, darkness, and confinement.

Men prepared to live with death inches away. The selection process began with a voluntary submission as not everyone wanted to go on hubot. Among the young men in the criggs marine, many preferred to serve on surface ships or in logistics duties. The rumor was clear. On yubot, the odds of dying were extremely high.

But for some, the idea of submarine combat, the close camaraderie, and the prestige that surrounded these units were appealing. Those who applied underwent exhaustive medical and psychological evaluations. It wasn’t enough to be healthy. They also had to demonstrate emotional stability.

Weeks of confinement, the pressure of command, claustrophobia, uncertainty. All of this demanded nerves of steel. Candidates were tested in closed chambers where they spent hours in isolation or were subjected to hearing tests in total darkness to measure their resistance to sensory stress. Once accepted, the training began. The first phase took place on land, generally at naval bases such as Keel, Wilhelms Haraven, or Fensburg.

There the recruits learned the basics of navigation, mechanics, electricity, and weapons handling. They trained with full-scale submarine models, practicing emergency procedures, hatch handling, and flooding drills. Everything was done with millimeter precision since the slightest error could be fatal in the middle of the ocean.

The next step was training in training submarines which operated in the calm waters of the Baltic Sea. There the trainee experienced for the first time the real life conditions of a yubot. Narrow corridors, variable temperatures, constant humidity and constant noise. Training focused on operating as a team.

Each man had to know his role and that of his colleagues. On a submarine, there was no room for improvisation. A typical crew consisted of between 45 and 60 men, depending on the type of hubot. Everyone had to be familiar with the ship’s systems. Diesel engines, electric batteries, the diving system, periscopes, the oxygen system, and torpedo tubes.

Even the cooks received basic technical training in case they needed to fill in in the event of casualties. Emergency preparedness was a fundamental part of the training. Instructors recreated engine failures, simulated fires, water leaks, and power outages. The recruits had to react in seconds, not only to save the submarine, but also to save each other.

They also trained in the use of the emergency respirator, a small oxygen cylinder that could give them a few extra minutes of life in the event of a flood or gas leak. Discipline was strict, but so was camaraderie. The training not only sought to develop competent technicians, but to consolidate a team that functioned as a single entity. They slept together, ate together, and took turns keeping night watches.

They were taught to read each other’s body language. Silence was often the norm on the submarine. Understanding each other without words was a valuable skill. As the conflict progressed and casualties mounted, the pace of training accelerated. It was no longer possible to dedicate a year to training sailors as at the beginning of the war.

Some crew members arrived on their first missions with barely three months of training. This generated tension. Many veteran captains distrusted the youngsters and there were frequent cases of recruits collapsing during their first days at sea. Central to the training was the submarine commanders, the Kalon.

These officers were selected from the best of the cre marine and were required to possess a combination of analytical composure and charisma. They were trained separately in advanced simulators and with tactical tests. They learned to calculate routes, manage supplies, and interpret enemy signals. Their training included meteorological studies, astronomical navigation, and convoy evasion.

Some like Otto Cretchmer and Eric Top became living legends. The sailors were also instructed in physical endurance. Despite the confined space, they were required to keep their bodies in shape through push-ups, sit-ups, and breathing exercises, which were part of their daily routine.

Lung capacity could mean the difference between life and death in the event of a loss of pressure or a final escape. One of the most important aspects of training, though less well-known, was psychological training regarding death. Crew members were openly informed about the fate that could await them. They were shown footage of sunken submarines and taught how to avoid panic if trapped. Risk acceptance was part of the process. The final oath wasn’t mandatory, but many took it by choice.

And bisum toad, meaning I serve with honor and until death. These weren’t just words. They were a reality. Once on board, sailors continued to learn. And on the battlefield, each mission was a lesson. Veterans instructed rookies, the captain corrected or discussed maneuvers with the officers, and the mechanics adapted and incorporated new solutions to recurring problems.

As technology advanced, sonar operators studied and learned to interpret new echoes or signals. And when they returned to port, if they returned at all, they underwent technical debriefings where they recounted what worked and what failed. Everything served to improve, but there was also time, albeit minimal, for humanity. Before setting sail, the crew members received a personal letter from Admiral Donuts wishing them luck and reminding them of the importance of their mission. Mothers, wives, or girlfriends might send small packages containing letters, photos, or candy.

Many carried amulets, religious images, or lucky charms sewn onto their uniforms. When they were finally assigned a real mission, embarcation day was solemn. The submarine departed, escorted by salutes, flags, and sometimes even a military band. But once past the coast, the real journey began.

A long, dark tunnel with no promise of return. Those who survived the first voyage were considered initiates. They had conquered their own fears, and that inside a yubot was a form of maturity. Everyone knew once inside, there was no turning back. every day the same night what terrible life was like inside a Nazi submarine.

Once the submarine left the harbor and entered the Atlantic, reality changed completely. What might have seemed like a heroic mission to civilians was something else from the inside. A daily struggle against confinement, silence, water pressure, and one’s own body. Living on a yubot was like inhabiting a parallel universe where the notions of day and night disappeared where time stretched and normaly was a distant word.

The space inside a German submarine was tiny. Every corner was occupied by something. Engines, batteries, torpedoes, cables, food supplies, men. In the early days of sailing, the passageways were literally blocked by sacks of potatoes, water cans, tin cans, tools, and barrels of supplementary fuel.

You had to climb over them to move. Only as the food and fuel were consumed did the space begin to free up. The crew was organized into rotating shifts, generally 4 hours on and 4 hours off, but rest was a relative term. There weren’t enough beds for everyone in a system known as hot bunking.

Three or four men shared the same bunk in shifts. While one slept, another worked, and a third prepared for duty. The blankets were damp, soaked with sweat and salt, and rarely dried completely. Ventilation was poor, and stale air was a constant enemy. During prolonged immersion, carbon dioxide slowly accumulated.

Air filters could alleviate the situation, but not completely eliminated. Many sailors suffered from chronic headaches, dizziness, and even mild hallucinations. To prevent collapse, artificial oxygen tablets were administered, and each breath was rationed. Smoking was strictly prohibited underwater. Hygienic conditions were minimal.

There was only one functional toilet located at the front of the submarine next to the torpedo tubes. If the submarine was submerged at a deep level, the drainage system could collapse and the waste water had to be stored until it could be expelled at the surface. Accidents were not uncommon, forcing the bathroom to be closed for days.

In these situations, buckets, towels, or simple bottles were used. Fresh water was another precious commodity. It was used strictly for drinking and cooking. There were no showers, no laundry, and sailors could go weeks without washing. The smell inside the submarine became part of the atmosphere.

A mixture of sweat, oil, salt, fermented food, rubber, and diesel fuel. It was so pervasive that many divers were recognizable by smell upon returning to land. The food was simple, caloric, and repetitive. In the first weeks, they ate relatively well. sausages, bread, fruit, canned meat, and soup. But as the days passed, the fresh food disappeared. Bread stale, fruit rotted, and preserves became the norm.

The cook known as dear smuty was a respected figure. He had to manage to feed 50 men in a tiny space with a single burner kitchen in constant motion. Good cooks were considered treasures on board. Despite everything, the routine was strict. Each crew member had a specific role assigned.

sonar operator, helmsman, torpedoman, mechanic, chief engineer, nurse. Everyone worked under the supervision of the Kon, the captain, and the first officer. Respect for the hierarchy was absolute, and orders were carried out without question. Discipline was not a matter of pride, but of survival, but technical work wasn’t everything, and an emotional battle was also waged.

The monotony of the environment, the lack of sunlight, the constant threat of detection, and the impossibility of escape generated a climate of constant tension. Every sound was significant. A pipe rattle, an engine shift, a hull vibration. Fear settled silently, and every deep dive was a test of nerves. When a yubot was spotted, the hunt began.

Depth charges were dropped from Allied destroyers. Explosions rocked the hull. Lights flickered. Valves popped loose. Everything creaked. Men clung to the walls, biting their lips, some praying. The sound of a charge exploding nearby was deafening. Technology of the deep, the evolution of yubot throughout the conflict. When World War II broke out in September 1939, the Creeks Marine had just over 50 operational yubot.

It seemed a modest number for a global conflict, but those first Ubot were key pieces of Hitler’s plan to strangle Britain from the depths. What followed was a desperate technological race. On the one hand, Germany needed to build more and better submarines. On the other, the Allies were developing increasingly effective countermeasures. Thus was written the history of yubot evolution.

The most iconic model of the early war years was the type 7 in its A, B, and C variants. It was a robust medium-sized attack submarine, easy to produce and maintain with a length of about 67 m and capacity for about 45 crew members. The Type 7 and was a machine designed for missions of between 30 and 40 days in the Atlantic.

Its main armament consisted of five torpedo tubes, four in the bow and one in the stern, as well as an anti-aircraft gun and another on the deck. This type of submarine became the true workhorse of German submarine warfare. It was maneuverable and reliable, and more than 700 units were produced throughout the conflict. But it was not without limitations.

Its submerged time was relatively short, and it had to surface frequently to recharge batteries using its diesel engines. As the conflict progressed and Allied pressure increased, German naval engineers began looking for new solutions. Thus was born the Type 9, an oceangoing submarine with greater autonomy and size. Measuring up to 76 m in length, it could travel greater distances, ideal for operations off the east coast of the United States, the Caribbean, or even the Indian Ocean, and carry more torpedoes on board. Its ability to operate far from European bases made it the ideal platform for

long range missions, including transporting technology to Japan or patrols off Africa. However, the great Achilles heel of both models, the seventh and 9th, was the same, the need to surface frequently. This vulnerability was exploited by the Allies beginning in 1942 when they began to dominate the Atlantic skies with radar equipped air patrols.

Every time a yubot surfaced, it became an easy target. The Creeks Marine attempted to mitigate this threat with small advances. One of these was the Schnorhal, a retractable tube that allowed the submarine to take in air and expel gases while cruising at periscopic height without needing to fully surface.

This technology, adapted from captured Dutch models, was introduced too late and suffered technical problems that limited its effectiveness, but it represented an important step toward the modern submarine. At the same time, improvements were made to electric propulsion, acoustic detection systems, and hull armor. But the great hope of Donuts and the high command arrived in 1944.

The Type 21, the so-called Electro Boot, a revolutionary submarine designed from the ground up to operate almost permanently underwater. The Type 21 was the culmination of years of experience and technological desperation. With a hydrodnamic design that made it faster submerged than on the surface, something unheard of until then, the type ventidon could reach underwater speeds of up to 17 knots and remain submerged for several days at a time thanks to its highcapacity batteries. Its recharging system was

faster, its acoustic profile more discreet, and its sensors much more advanced. This submarine also innovated in other aspects. It included passive radars, an automated fire control system, silent electric motors, and even a more functional galley, and a more ergonomic design for the crew. It was in every sense a generational leap.

But it came too late. By the time the first type 21sts were ready for operation, the Third Reich was already in full retreat. Only two units carried out active combat patrols. The rest were captured in shipyards or sunk by the Germans themselves to prevent their use by the Allies. Even so, the impact of its design was so profound that postwar navies, especially the Soviet and American, drew inspiration from the Type 21 for their first nuclear submarines.

In parallel, Germany attempted to experiment with even smaller and more versatile models. Thus were born submarines such as the Bber, the Mulch, and the Seahund. These vessels were crewed by one or two men, carried only a pair of torpedoes, and were designed for coastal operations, sabotage, or surprise attacks on port areas.

Although technically ingenious, these mini submarines were extremely vulnerable, and the mortality rate among their crew exceeded 90%, the evolution also included changes in operating doctrine. At the beginning of the war, hubot operated more independently. With the introduction of Wolfpacks, submarines began to coordinate group attacks.

Later, as losses mounted, a dispersal tactic was reverted to minimize risks, and Ubot went from being bold hunters to becoming, in many cases, cautious prey. Their use also diversified for logistical purposes. Some Ubot were modified for special missions such as carrying anti-aircraft missiles, launching sea mines, deploying sabotur commandos, or installing automated weather stations on remote shores as was the case in Newf Finland.

The German industrial effort to produce yubot was colossal. More than 1,150 yubot were built throughout the war involving tens of thousands of workers in shipyards such as those in Hamburg, Bremen, Danzig, and Keel. Underground tunnels and giant bunkers were used to protect the assembly lines from Allied bombing.

Some of these bunkers, such as the one in Lauron in occupied France, still survive today as monuments to war engineering. Toward the end of the conflict, however, neither innovation nor mass production was enough. The Allies dominated the air, deciphered German codes, and patrolled with new generations of destroyers and anti-ubmarine aircraft. The lifespan of the new Yubot was weeks. Many didn’t even complete their first mission.

Technological advances couldn’t compensate for the speed with which the war was tilting against Germany. And yet, even in their fall, the Yubot left a profound mark. They redefined naval warfare. They forced the Allies to change their maritime strategy. And they forced everyone to consider for the first time an enemy that couldn’t be seen, that made no noise, but that could appear on any coast on the planet.

The return of Moby Dick, the most sinister tragedies befalling Hubot. Throughout World War II, Germanot were the protagonists of daring operations, surprise attacks, and feats of navigation. But behind that facade of steel and strategy lay profound human tragedies, some of them shocking. Submarine warfare was not just a technical battle.

It was a game of life or death, where the slightest error could seal the fate of dozens of men. One of the most memorable tragedies was that of U1206, which occurred in April 1945 in the final days of the conflict. The submarine, recently launched and equipped with new pressurized toilet technology, a system so advanced it required special training, suffered an unusual incident.

One of the crew members, not fully understanding the mechanism, incorrectly activated a valve while the submarine was at great depth. The result was that sewage and gases began to flood the compartment, forcing the commander to immediately surface off the Scottish coast. In doing so, U206 was spotted by British aircraft and attacked. The commander ordered the submarine abandoned and scuttled.

Four men died. It was an absurd tragedy where technology and haste worked against them. Another dramatic case was that of U864, which sank in February 1945 with all hands off the coast of Norway. Its mission was to transport military technology, reactor parts, and enriched uranium to Japan.

But it was intercepted by the British submarine HMS Venturer, which sank it in a historic maneuver, the only submarine battle in history where both adversaries were submerged. U864 broke in two and sank to a depth of more than 150 m along with its 73 crew members. The environmental impact of its radioactive cargo is still being studied today.

One of the most numerous tragedies was that of the Yubot U47 commanded by the famous commander Ga Pin, hero of the Scarpa flow attack. The Yubot disappeared in March 1941 while on patrol in the North Atlantic. Neither its trace nor that of its 45man crew was ever found. For decades, there was speculation that it had been sunk by depth charges, but theories of an internal explosion or accidental collision also emerged.

Prien’s figure was erased from Nazi propaganda without explanation, and his death became a symbol of the mystery and constant danger of submarine warfare. Also shocking was the fate of the Yubot U99, one of the most successful German submarines under the command of Otto Cretchmer, nicknamed the Silent Wolf. With an impressive figure of more than 200,000 tons sunk, Cretchmer became a legend.

But in March 1941, his U999 was located by British destroyers and attacked with depth charges. The submarine was forced to surface and Cretchmer ordered an evacuation. Although most of its crew was rescued, three sailors died in the attack. Cretchmer spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war in Canada. Unlike many such tragedies, the commander’s leadership prevented total catastrophe.

However, the fate of U250 was less fortunate. This submarine was sunk in the Gulf of Finland in July 1944 by a Soviet depth charge. Only six men survived and were captured. The rest of the crew, including experienced officers, died trapped in the depths. The most shocking thing came next. The Soviet Union recovered the entire submarine from the seabed, towed it to a shipyard, and used it as a source of technical intelligence.

U250 became a sunken war prize. Another poignant story was that of U222 sunk by mistake during a training exercise. On September 2nd, 1942 off the German coast, a coastal artillery battery mistook it for an enemy submarine. U222 was hit by a direct shell causing an internal explosion. 42 crew members died.

It was a tragic accident, a product of operational chaos during the accelerated training at the end of the war. Also worth remembering is Yubot U159 sunk in the South Atlantic in March 1944. It was carrying experimental torpedoes, including acoustically guided models. It was located by an American Grumman Avenger aircraft which attacked it with depth charges.

When the torpedoes stored on deck detonated, the submarine exploded in midair, instantly killing most of the crew, and only five menaged to jump into the sea. Of those, only one was rescued alive. The rest died from their wounds or were attacked by sharks. One of the most iconic tragedies of the end of the conflict was that of the Yubot U977, not because of its sinking, but because of its incredible journey.

The submarine left Norway in May 1945, just as Germany was surrendering. Its commander, Hines Sheffer, decided not to surrender and took his yubot to Argentina. The journey lasted 66 days underwater. one of the longest dives on record. Although they reached the coast without incident, many of the sailors were psychologically scarred.

Several fell ill on the voyage. The episode was exploited by the press to fuel rumors of Nazi escapes to South America. Although it was never proven that they were carrying secret passengers. There are also little known tragedies such as that of the U 1063 sunk near the English coast by depth charges after having formally surrendered days before and U486 destroyed by an Allied torpedo while carrying secret weapons.

In this case, the torpedo was launched by a British submarine that had broken its radio silence to intercept the enemy signal. An extremely risky undertaking. Mortality among yubot sailors was one of the highest of the entire war. Of approximately 40,000 men who served in the German yubot force, more than 28,000 died. That means that seven out of 10 men who boarded a yubot never returned.

Most of them disappeared without a trace into the depths of the North Atlantic, the North Sea, or the Mediterranean. For their families, the tragedy was twofold. Often there was no body, no grave, no explanation, just a telegram. The sea had swallowed them up. And yet each new crew boarded the submarine with the same resignation.

They knew the odds were against them, but the mission continued. Sometimes out of loyalty, sometimes out of camaraderie, sometimes simply because there was no other option. The fall of the Leviathans. What happened to the Yubot after the end of the war? When Germany signed its unconditional surrender on May 8th, 1945, more than 150 German hubot were still patrolling the world’s oceans.

Some sailed alone, others were part of flatillas trying to carry out their final orders, while several were docked in occupied ports or awaiting instructions below the surface. Within hours, all were officially stateless, flagless, and missionless. The Yubot fleet, which had been the terror of the Atlantic, became overnight an uncomfortable remnant of a defeated military machine.

From that moment on, an operation known as Operation Deadlight began, one of the largest naval disarmament efforts in history. Its objective was to locate, escort, and deliberately sink all surrendered or captured Hubot to prevent their reuse or their technology from falling into the wrong hands.

It was not only about disarming Germany, but also about sending a message. The Third Reichs submarine weapon had to be completely wiped off the map. The Ubot were assembled in Allied ports such as London Derry in Northern Ireland and Lock Ryan in Scotland. Dozens of units were lined up there, many of them battered, rusty, their insignia covered in paint, and their crews detained.

The German sailors, mostly young survivors of suicide missions, were interned in prison camps. Many would not return to Germany for several years. In total, more than 150 Yubot were deliberately sunk between 1945 and 1946 as part of this operation. The procedure consisted of towing them out to sea and then using them as targets for aerial gunfire tests or sinking them directly with explosive charges.

Some sank during towing, others held out until they were literally riddled by British and American forces. Operation Deadlight was not without its problems. Several Ubot broke loose during maneuvers and sank in unplanned positions. Some broke apart before reaching the open sea. The North Atlantic climate, currents, and deteriorating hulls meant many were lost in uncontrolled conditions.

Today, the remains of more than 100 Yubot rest scattered on the seabed off Ireland and Scotland, forming a silent underwater graveyard. However, not all Ubot were sunk. A significant number were captured intact by the Allies for study purposes.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union vied for access to German technology. New generation submarines such as the Type 21 sparked enormous interest due to their advanced design and military potential. Several of them were taken to American, Soviet or British ports to be dismantled and analyzed piece by piece. One of the most famous captured hubot was U505 captured by the US Navy in 1944 before the end of the war.

It was towed to American soil where it was extensively studied. Its coding system, propulsion system, and armorament were used to improve allied submarines. U505 was later restored and is now part of a permanent exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, the only original on display in the Western Hemisphere. The Soviets for their part received some yubot as part of war reparations.

The most notable was U2529, one of the few operational type phumas which was incorporated into the Soviet fleet under the designation B27. For years, Russian engineers studied its structure, battery system, and ability to operate submerged for long periods. This knowledge was critical to the design of the first postwar Soviet submarines.

Hubot that had not been registered during the surrender were also discovered. Some commanders reluctant to surrender decided to scuttle their submarines with all hands. In many cases, these were decisions made out of pride, loyalty, or simply fear of reprisals.

U853, for example, continued operating even after the announcement of the German surrender and was finally sunk off the coast of Rhode Island in May 1945, 3 days after the official end of the war. Other submarines managed to reach neutral ports. U530 and U977, for example, arrived in Argentina weeks after the surrender, sparking a wave of speculation and conspiracy theories.

It was said they were carrying Nazi leaders, gold, and even Hitler’s remains. Although these stories were never proven, both submarines were seized by Argentine authorities and handed over to the United States, where they were eventually sunk as part of naval tests.

The end of the Yubot was also the end of a particular military corps, themsine submariners. By the end of the war, more than 75% of them had died. The few who returned home did so as ghosts, carrying a mixture of guilt, trauma, and silence. Postwar Germany was neither prepared to honor nor openly condemn them. They were simply forgotten for years.

In technological terms, the Yubot of the Third Reich paved the way for modern submarine warfare. Its design, especially that of the Type 21, served as the basis for future nuclear submarines of the Cold War. The lessons learned in the oceans of the conflict were not lost. They were absorbed, improved, transformed. But beyond the technical aspects, what remained was a story of lives trapped between the steel plates, the darkness, and the silence.

A submarine army that operated beneath the sea without final glory, without a victory parade. The lie in the waves, the salvage of U869, the yubot that wasn’t meant to be there. For nearly half a century, the German yubot U869 was officially considered lost near Gibraltar with no further details. The Creeks Marine had reported the submarine missing in February 1945, and for decades, no one questioned the report.

But in 1991, what began as a recreational diving expedition off the coast of New Jersey turned into one of the most mysterious and exciting discoveries in the history of military underwater archaeology. It all began when a group of technical divers led by John Chatterton and Richie Col, explorers passionate about shipwrecks, located the remains of a submarine at a depth of approximately 70 m and more than 100 km off the Atlantic coast of the United States. The first thing that surprised them was that the site didn’t match any known shipwreck in the area.

And the second, even more shocking, was that it was a German submarine from World War II. The wreckage was well preserved, although partially collapsed. The main structure still retained the design lines of the type 1 XC/40, a longrange oceangoing model. The propellers, periscopes, and hatches all indicated that it was a yubot.

But there was a problem. According to historical records, no German yubot had ever been sunk at that point in the Atlantic. A parallel investigation then began. On the one hand, a physical exploration of the submarine through extremely dangerous dives due to the depth, visibility, and possibility of collapse.

And on the other, a documentary search that sought to cross-reference war logs, mission reports, classified archives, and testimonies. For several years, the divers carried out successive expeditions, risking their lives on each dive. It was not an official project, nor was it funded by any institution.

It was an obsessive search driven by an unanswered question. How had a German yubot gotten to that location, and why didn’t anyone know? On one of the most revealing dives, the divers managed to enter the torpedo compartment and found tools inscribed in German machine parts with serial numbers. And finally, the greatest find, a valve marked U869.

It was the confirmation they were looking for. They had found U869, presumed missing thousands of miles away. The discovery forced a rewrite of history since, according to German documents, U869 had been sent on a mission to the North Atlantic, initially bound for the coast of Morocco.

However, due to changes in patrol orders, the submarine was likely instructed to head toward the American coast where other Yubot were operating as part of the Reich’s last desperate offensives. The problem was that the order would have arrived late or in ambiguous form. The confusion, typical of the communications chaos of the final months of the war sealed its fate.

The conditions under which U869 was sunk remain a matter of debate. One theory supported by the divers suggests that the yubot was destroyed by one of its own depth charges, perhaps during a poorly executed defensive maneuver. Another hypothesis suggests that it was hit by charges dropped by American destroyers patrolling the area.

However, no contemporary Allied source records such a sinking, making the case a complete mystery. During the dives, the divers also found human remains, transforming the discovery into an ethical and emotional issue. They decided to treat the site as a war grave. They removed no bodies or personal effects.

The U869, submerged and silent, went from being an object of technical curiosity to an underwater memorial. One of the most poignant details was the discovery of a partially preserved sailor’s personal diary, which mentioned relatives in Hamburg and a girlfriend awaiting the return of one of the sailors.

These fragments, mostly illeible, were recovered by divers and handed over to German authorities who contacted the descendants. It was a symbolic closure to a story forgotten for more than 45 years. The discovery of U869 also opened the door to a broader debate. How many missing yubot are still missing? Throughout the war, more than 50 German hubot were reported lost without explanation.

Some would have been victims of mines, others of navigational errors or mechanical incidents. Some may have sunk in uncharted parts of the ocean. Today, the U869 remains on the seabed, a war sanctuary officially recognized by Germany and protected by international law. The area where it lies is not marked by buoys or monuments, but is visited annually by specialized divers who pay silent tribute to the crew.

Poisoned water. Operation U864, the yubot carrying a cargo that continues to kill the planet. When the German submarine U864 departed from the Keel Naval Base in December 1944, its destination was neither a patrol nor a combat mission.

It had a secret cargo and a strategic mission to cross the Atlantic round the Cape of Good Hope and reach Japan. It was part of Operation Caesar, a desperate effort by the Third Reich to transfer technology, engineers, aircraft engines, and nuclear materials to the Japanese Empire with whom it shared an alliance in its final hours of resistance. But U864 never reached its destination. In February 1945, off the coast of Fedj, Western Norway, the submarine was intercepted by HMS Venturer, a British submarine commanded by Latutenant James Londers.

What happened that day was unique in naval history, a battle between two completely submerged Hubot. Londers, without visual contact, estimated the U864’s position, speed, and depth, and launched a series of torpedoes in a carefully calculated sequence. One of them hit squarely.

The German submarine broke in two and sank to the bottom, taking all 73 crew members with it, and a secret that wouldn’t come to light until almost six decades later. For decades, the exact location of the wreck remained unknown. Precise records didn’t exist, and the story was relegated to a footnote in British naval history. However, in 2003, a Norwegian expedition conducting oceanographic studies in the area located metallic structures at a depth of more than 150 m.

What began as a geological anomaly soon became an international investigation. When a robotic submarine descended with highresolution cameras, the discovery was confirmed. The remains were those of the U864, still fragmented, covered by sediment, but visibly well preserved.

What was even more surprising was the discovery of sealed cylindrical containers, many of them still intact. Upon analysis, their contents were revealed. more than 60 tons of metallic mercury stored in ceramic jars inside steel vessels. The mercury was intended to reach Japan, possibly as a component in navigation systems or experimental developments.

But its presence on the Norwegian seabed posed a very serious environmental threat because mercury is highly toxic and over the decades some of the jars had begun to corrode, leaking small amounts into the marine ecosystem. The Norwegian government upon learning of the magnitude of the discovery faced a monumental dilemma.

How to proceed with a shipwreck that is at the same time a war grave, an ecological risk and a historical fragment. After years of deliberation, technical studies and pressure from environmental organizations. A final decision was made in 2017. U864 would not be extracted but encapsulated in the seabed. The chosen solution consisted of completely covering the submarine with a slab of stone and underwater concrete, sealing the wreckage to prevent any future mercury leakage. The operation was extremely delicate, not only because of

the depth and sea conditions in that area, but also because any improper movement could further fracture the containers and release the toxic contents. Despite the technical solution, the controversy persisted. Some, including historians and associations of families of the deceased sailors, argued that burying the yubot was equivalent to erasing a chapter of history and that a gradual and controlled extraction should have been attempted. Others, however, considered the ecological risk to be more important than material preservation.

The truth is that U864 was buried forever, a capsule of steel, death, and poison sealed beneath tons of rock. But even after its encapsulation, the story of U864 continued to generate questions and theories. One of them pointed to the exact contents of the cargo.

While the presence of Mercury was confirmed, there was also speculation that other transported items such as messes jet engine parts, missile plans, advanced optical technology, and even small amounts of radioactive material may have been destined for Japanese laboratories. Another curiosity was the figure of James Lunders, the British commander who sank the U864.

His feet was so precise that many naval historians compare it to an underwater chess match. However, Londers never fully exploited his fame. He died in 1988, unaware that decades later his maneuver would be studied as a masterpiece of submarine calculation and tactics. Today, the exact spot where the U864 lies is marked on Norwegian nautical charts as a restricted area, and access is limited.

There are no visible monuments or commemorative plaques, only the sea, knowing what it hides. And beneath it, the remains of a submarine that never fulfilled its mission, but whose legacy, poisoned and mysterious, continues to float on the currents of history. bones in the sea. Other yubot recovered in recent decades. Many of the World War II hubot were pulverized by depth charges or forgotten in the depths of the Atlantic.

But just as many disappeared mysteriously or sank due to mechanical and human failure. Over the past few decades, a considerable number of German hubot have been rediscovered, salvaged, preserved, or studied for historical, technical, or even tourist purposes. Some of these discoveries resulting from events we described when discussing the tragedies suffered by these vessels did not have the media impact of U869 or U864 considered the most important discoveries in this field.

However, each one contributes another piece to the complex puzzle of submarine warfare in the Third Reich. One of the most notable cases is that of U534 found in 1986 off the coast of Denmark in the Catagat Strait. This submarine, a type Nike C/40, was sunk on May 5th, 1945 by a British bomber just 3 days before the end of the war in Europe. The crew managed to partially evacuate the submarine, but three sailors died during the attack.

Curiously, U534 was on route to Norway, possibly as part of a secret evacuation or on a lastminute mission to South America. The mystery surrounding its fate and exact cargo has fueled multiple theories. The submarine was fully recovered through a private salvage operation financed by a Danish businessman.

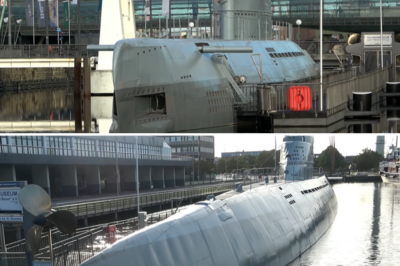

Although damaged by the attack and corrosion, the hull remained surprisingly intact. U534 was partially restored and for years was on open air display in the port of Birkenhead, United Kingdom. It is currently part of a sectioned exhibition at the Yuboat story museum where visitors can view its interior through glass panels. It is one of the few original Yubot on display outside of Germany.

Another curious case is that of U995, a type 7C/41, one of the most widely used models by the creeks marine. At the end of the war, this submarine was captured by the British and handed over to the Norwegian Navy, which used it as a training vessel under the name KA. In 1965, it was returned to Germany as an object of historical value. Today, U995 is stranded on Labbo Beach near Keel, converted into a floating museum that can be visited.

Along with U505 from Chicago, it is one of the few Yubot preserved in near original condition with its internal equipment intact. U2540, meanwhile, has an even more unusual story. It was a type 21, the most advanced submarine model built by Germany during the war. It was launched in 1945, but never saw combat. In May of that same year, its own crew sank it near Flynnburg to avoid capture.

She remained underwater for over a decade until 1957 when she was rescued by the Federal Republic of Germany, refloated, modernized, and returned to service as an experimental submarine under the name Wilhelm Bower. She served in the Bundus Marine until 1982. Today, U2540 is a floating museum in Brema and represents the only fully restored type 21 open to the public.

More recent discoveries made by civilian researchers, fishermen, and underwater explorers are also available. In 2017, a team of Dutch divers found U31 off the coast of Tur Shelling, one of the first Ubot lost in the war, missing since 1939. The discovery closed a chapter that had been open for over 75 years and allowed the descendants of her crew to finally locate the graves of their relatives.

Off the coasts of northern France, especially around Lauron, San Nazair, and Lar Rochelle, dozens of yubot wrecks still lie buried beneath the rubble of bunkers. Some were blown up by retreating German troops, others by the Allies. In some cases, the Yubot were trapped in the concrete structures, becoming part of the abandoned industrial landscape.

In Norway, which was a key strategic base for German yubot operations in the North Atlantic, several partial hulls and wrecks of hubot have been found in the fjords. Many of them are badly deteriorated, but are still the subject of archaeological study.

The aforementioned U864 is only one of the best known, but at least a dozen more have been identified over the years by civilian and government teams. In other cases, the submarines were literally sold for scrap or melted down as was the case with many of the yubot captured after the war in French, Danish or Baltic ports. Only a minority were preserved for educational or commemorative purposes.

The rest were reduced to recycled steel. A special chapter is represented by the yubot that disappeared without official explanation. Naval historians still debate the fate of at least 20 submarines that never returned and whose sinking coordinates remain uncertain. Some were probably destroyed by mines, others by mechanical accidents or human error.

The sea swallowed them without leaving a trace. In recent years, advances in underwater scanning technology have allowed for new locations. Marine archaeology teams such as those from Keel University and the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research have begun to precisely map the seabed where the wrecks are located. These projects not only have historical value, they also allow for the assessment of ecological risks such as fuel leaks or unstable ammunition.

In this context, Germanot have gone from being weapons of war to objects of collective memory. They are studied, filmed, and visited. Many of them function as floating museums, memorials to the dead, or even as artificial reefs for marine life. They are in many ways the last submerged witnesses of a war that was also fought in the absolute silence of the depths.

Thus, the legacy of the Yubot is dispersed among museum display cases, images captured by underwater robots, declassified archives, and the invisible graves that still lie beneath the waves. moves.

News

“Where do you think you’re going?! Your guests have arrived!” the mother-in-law exclaimed—only to get exactly the answer she deserved.

Anna carefully parted the curtain and looked out the window. The familiar white Logan pulled up to the gate, and…

The husband left for a younger woman, leaving his wife with enormous debts. A year later, he saw her behind the wheel of a car that cost as much as his entire company.

“I’d leave you the keys, but there’s no point.” Elena slowly raised her head. Andrey was standing in the doorway,…

CH1 THE ENTIRE World War II From The German Perspective | Documentary in PURE COLOR

When Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Germany was still bound by the impositions of the Treaty of…

CH1 Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

four hundred planes vanished 400 aircraft launched into the Pacific sky only a handful returned what happened on June 19th,…

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

End of content

No more pages to load