At dawn on July 10th, 1945, Argentine fishermen off the naval base at Mardel Plata saw an unexpected silhouette emerge in the distance. A large hubot running on the surface suddenly appeared heading toward the harbor entrance. This would be U530 of the German Creeks Marine, arriving unannounced 2 months after World War II had ended in Europe.

The vessel’s surprise appearance so long after VE Day would spark international headlines, official investigations, and a lasting legend of a final secret mission. This is the story of U530, the Yubot that escaped to Argentina. U530 was a type 9 cuboat, a longrange design meant for extended patrols far from home ports.

Measuring about 251 ft in length and displacing over 1,100 tons surfaced, it carried six torpedo tubes, four forward, two aft, and up to 22 torpedoes. Earlier in the war, its class was equipped with a 10.5 cm deck gun for surface combat, though many hubots had these removed later in the war. U530’s conning tower also mounted anti-aircraft guns and carried a hoenhe radar transmitter for detecting enemy ships or aircraft.

With powerful diesel engines and a new snorkel device, U530 could travel 13,000 plus nautical miles and even run submerged for extended periods. Ideal for stealthy operations across the Atlantic. The submarine’s crew normally numbered about 44 to 54 officers and enlisted men. U530’s wartime service had been eventful.

Under a previous captain, it conducted six combat patrols, sinking two Allied merchant ships and damaging another. In January 1945, command passed to Oloyant Otto Vermouth, a 24-year-old veteran yubot officer. It was first command and he was eager to prove himself. He assumed command of U530 just as Nazi Germany was teetering on collapse.

Wormouth and his crew would soon find themselves on one of the most bizarre voyages in World War II. U530’s fateful final mission began in the last weeks of World War II. On March 3rd, 1945, Wermouth departed the Yubot base at Horton, Norway with orders to disrupt Allied shipping in the Western Atlantic. After a covert transit around the British Isles, mostly submerged to avoid overwhelming Allied air patrols, U530 reached the waters of North America by late April.

Initially assigned to hunt convoys near Halifax, Canada, Wermouth found few targets and decided to head south toward the busy sea lanes off New York. There in the first week of May 1945, U530 made several fruitless attacks on Allied ships. From May 4th to 7th, the Yubot fired nine torpedoes at convoys near the New York coast, but all either missed their targets or malfunctioned.

These would be the last shots. U530 ever fired in combat. On May 8th, 1945, Germany surrendered unconditionally, ending the war in Europe. At that moment, U530 was cruising in the Mid-Atlantic, roughly 1,000 mi east of Puerto Rico. Admiral Carl Dunitz, Hitler’s successor, had ordered all Hubot to cease hostilities and surrender at the nearest Allied port.

For Yubot crews, this directive transmitted with top priority meant the war was over. Dozens of submarines surfaced and gave themselves up in May while others scuttled themselves under the last ditch operation reanogen plan rather than be captured. Obereloidant Vermouth however made a fateful choice.

According to his later testimony, he doubted the surrender message was genuine and feared it might be an allied trick. Instead of reporting to an allied port, Burmouth decided to flee. Believing his men might receive better treatment in a far-off country, he set course for neutral Argentina, not realizing that Argentina had quietly declared war on Germany only weeks earlier.

Wormouth ordered the crew to cease all offensive operations and prepared for a long clandestine voyage. The submarine stayed submerged during daylight hours using its snorkel to run the diesel engines and recharge batteries while hiding just below the surface. By night, U530 would cautiously surface to make better speed in the open ocean.

Every precaution was taken to avoid drawing attention. The crew even refrained from using their radio except for routine weather reports. They navigated a securitous route passing east of Bermuda and crossing the equator in midJune 1945 under the cover of darkness. In accordance with Dunit’s standing instructions, Vermouth also began dumping anything that might be of value to Allied intelligence or pose a hazard during surrender.

Overboard went their remaining torpedoes minus one whose battery had exploded. the broken torpedo warhead and gyroscope, all coded signal books and the ship’s log book, and even the boat’s anti-aircraft ammunition and radar equipment. U530 was shedding weight and secrets as it crept towards South America.

By late June 1945, the Yubot had entered the South Atlantic, running low on provisions, but still undetected. Initially Burmouth considered surrendering at Myiramar near Buenosiris but ultimately chose Ma del Plata as the most suitable. On the night of July 9th 1945 U530 approached the coast of Argentina. After more than 70 days at sea since the German surrender, Burmouth’s crew prepared to give themselves up at last.

The Ubot surfaced off Mel Plata and cautiously inched toward the harbor, running on the surface under cover of darkness. The long journey was almost over. But the real mystery of U530 was just beginning. Just before sunrise on July 10th, 1945, U530 made its move. The German submarine’s crew hoisted a large white flag and turned on their navigation lights as they neared Mard Plata’s harbor entrance.

The sudden appearance of a yubot took the Argentine defenders by surprise. One account notes the sub slipped past a sentry who had his back turned to the sea. Once inside the port, Wormouth blinked the word Aliman submarino, German submarine by signal lamp, indicating his intention to surrender peacefully. Argentine naval personnel quickly mustered and surrounded the yubot.

U530 formally surrendered to the Argentine Navy on the morning of July 10th, 1945, ending its odyssey. All 54 crewmen were brought ashore, given hot food and even haircuts, then promptly placed under guard. The yubot that had roamed the Atlantic was now a prized captive docked at Argentina’s main naval base.

The immediate question was where had U530 come from and why now? When interrogated by Argentine officers, Oeloit Vermouth offered only a sketchy story. He admitted that on VE day May 8th, his submarine was operating in the North Atlantic and that he had decided to sail for Argentina to surrender there. However, Vermouth could not satisfactorily explain why the voyage had taken over 2 months when a direct trip should have been possible in a few weeks.

Suspicion grew when the Argentines discovered that U530 had arrived without its log book, without any torpedoes or deck gun, and with the crew carrying no personal identification papers at all. Wormouth claimed he had scuttled the log and secret materials at sea, as well as the unused munitions, but his vague answers about the yubot’s route and activities did little to ease speculation.

To make matters worse, he initially lied that the submarine’s engines were malfunctioning, only later confessing that he had deliberately sabotaged the diesel motors before entering port, pouring acid into them to ensure the yubot could not be easily reused. Such actions suggested Wormoth was hiding something about U530’s final mission.

News of the Yubot’s mysterious surrender spread quickly, reaching Allied authorities and neighboring countries. Within days, Argentina, which had only declared war on Germany in March 1945, found itself under intense international scrutiny over U530. The Argentine Navy moved the crew to an inland detention camp and agreed to hand the submarine over to the United States in the spirit of Allied cooperation.

US and Argentine intelligence officers subjected Vermouth and his men to extensive interrogation. Repeatedly the Germans denied carrying any passengers, fugitives, or valuable cargo. Wormouth insisted that at no time during the voyage had the U530 carried aboard any passengers of any nationality, civilian or military.

To skeptics, these denials were expected. If U530 had secret passengers or cargo, the crew would hardly confess it. The lack of a log book or clear timeline only fueled suspicions. Despite Wermouth’s evasiveness about the Yubot’s exact route and two-month delay, no concrete evidence of wrongdoing was immediately found.

The Argentine Navy’s official communicate, issued soon after, emphasized that no highranking Nazi officials were aboard U530. No one had been landed on Argentine shores, and the submarine had not been involved in any hostile acts like the recent sinking of the Brazilian cruiser Bajia. In short, Argentina publicly declared U530 surrender to be routine, but in private, many wondered if there was more to the story.

U530’s unexplained voyage set off a storm of rumors and conspiracy theories that linger to this day. In July 1945, the regional press and some allied officials openly speculated about sensational possibilities. One theory posited that U530 had made a clandestine detour to spirit away Adolf Hitler and Ever Brown to safety.

An Argentine reporter claimed to have seen a police report describing a mysterious yubot landing on the remote coast of Patagonia unloading a high-ranking officer and a civilian. Supposedly, Hitler and his wife disguised in men’s clothing. Around the same time, the FBI in the United States received unconfirmed reports that a German submarine had put ashore in southern Argentina or elsewhere in May 1945 with Hitler aboard.

These dramatic allegations captured headlines despite the lack of any hard evidence. U530 was also accused by a Brazilian admiral of torpedoing the cruiser Bajia on July 4th, 1945. Since the sub’s presence in the South Atlantic roughly coincided with that tragedy, another Brazilian naval officer speculated that U530 might even have come all the way from Japan, suggesting some last gasp axis collaboration.

The fact that U977, another German, arrived in Argentina 5 weeks later, surrendering on August 17th, 1945, only added fuel to the conspiracy fire. If two Yubot showed up in Argentina, some wondered, could they have been on secret missions to deliver Nazi leaders, warloot, or advanced technology to a safe haven? In reality, most of these theories have been debunked or remain unsupported by evidence.

A postwar Brazilian inquiry conclusively determined that Bajia was sunk by an accidental onboard explosion during gunnery drills, not by any submarine attack. No credible proof ever emerged linking U530 to Hitler’s escape. Exhaustive Allied investigations concluded with virtually no doubt that Hitler died in his bunker in May 1945.

Likewise, while many Nazi officials did flee to Argentina, most arriving by air or through other routes in the years after the war, there is no confirmed record of U530 transporting anyone or anything. Allied Naval Intelligence reports from 1945 note that U530’s crew all consistently denied any passengers or special cargo, and the physical inspection of the boat revealed no secret compartments beyond normal storage.

U77’s captain, who was interrogated separately, also maintained that his Ubot had no connection to U530’s voyage. While it is understandable why the unexplained delay and missing log fueled imagination, historians generally conclude that U530’s late surrender was an act of rogue obedience and self-preservation, not a Hollywood style Nazi escape plot.

Wormouth likely destroyed the log and weaponry to cover up his defiance of orders and to prevent any possible incrimination of his crew. In the end, the legend of U530 has outlived its reality, a reminder of how mystery can breed speculation. The incident did, however, prompt allied agencies to keep a close watch on postwar Nazi movements, and it contributed to Argentina’s reputation as a haven for fugitive Nazis, albeit mostly via different means.

After the surrender, U530’s crew spent several weeks under Argentine custody before being handed over to the United States for further interrogation. In August 1945, the US Navy took possession of U530 as a war prize, part of a program to study captured German technology. The submarine along with the later arriving U977 was towed to the Panama Canal and then up to the east coast of the US.

That autumn, U530 briefly tooured a few American port cities, a public exhibit of a defeated Yubot before the Navy decided it had outlived its usefulness. The men of U530 were eventually repatriated to Germany in 1947 after 2 years as PS. Oberelit Nutant Vermouth himself survived the war and lived into old age, although details of his later life are sparse.

In the end, no crew members were charged with wrongdoing beyond failing to follow the original surrender order. The final fate of U530 came in late 1947 when the US Navy selected the submarine for destruction as a target. On November 20th, 1947 off the coast of Cape Cod, the American submarine USS Toro lined up U530 in its periscope and fired a live torpedo.

The weapon struck U530 amid ships, blowing the Yubot in two and sending it to the bottom of the Atlantic in a fiery plume of water and debris. What had begun as a stealthy commerce raider for the Creeks marine ended as scrap metal on the ocean floor of Massachusetts. A quiet conclusion to a voyage shrouded in mystery. U530’s strange journey left a legacy disproportionate to its modest wartime record.

In Argentina, the Yubot’s arrival in 1945 became part of the folklore of the immediate postwar era, reinforcing suspicions about Nazi activities in South America. The incident did push Argentine authorities to demonstrate cooperation with the Allies, as seen by their swift transfer of the sub and crew to US custody. Internationally, U530 and the later U977 served as stark evidence that not every enemy unit surrendered exactly when and where expected.

A few stragglers charted their own course in the chaotic final days of World War II. U530 remains an intriguing case study of Operation Regan Bogen’s aftermath and the psyche of Yubot crews facing defeat. The mystery of U530 continues to fascinate. a real world footnote where fact and legend have often intertwined. While conspiracy theorists have woven elaborate tales around U530’s final mission, the consensus of historical evidence is far more grounded.

The Hubot’s 2-month disappearance was likely spent hiding from Allied retribution, not smuggling Hitler to a Patagonian hideout. Yet, the very lack of a definitive log or full disclosure from Wormouth means U530 story retains several unanswered questions. In the end, this lone submarine surrender in a distant port encapsulates the tumultuous end of World War II.

U530’s voyage to Argentina has secured its place as one of naval history’s strangest final missions ever recorded.

News

“Where do you think you’re going?! Your guests have arrived!” the mother-in-law exclaimed—only to get exactly the answer she deserved.

Anna carefully parted the curtain and looked out the window. The familiar white Logan pulled up to the gate, and…

The husband left for a younger woman, leaving his wife with enormous debts. A year later, he saw her behind the wheel of a car that cost as much as his entire company.

“I’d leave you the keys, but there’s no point.” Elena slowly raised her head. Andrey was standing in the doorway,…

CH1 THE ENTIRE World War II From The German Perspective | Documentary in PURE COLOR

When Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in January 1933, Germany was still bound by the impositions of the Treaty of…

CH1 Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

four hundred planes vanished 400 aircraft launched into the Pacific sky only a handful returned what happened on June 19th,…

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

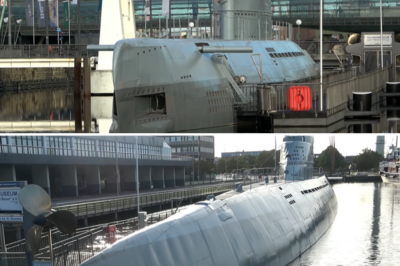

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

End of content

No more pages to load