May 1945, Germany surrenders and with it falls one of the most feared weapons of the Second World War, the Tiger Tank. Across battlefields from Normandy to the Eastern Front, hundreds of these massive machines sit abandoned, destroyed, or captured. The Allies suddenly possess the most powerful tanks of the war, and a race begins to locate, test, and decide the fate of every Tiger they can find.

In early May 1945, as the Third Reich collapsed, the Panzer Waffa had virtually ceased to exist as a fighting force. Tiger 1 and Tiger 2 tanks stood immobilized across Europe, victims of fuel shortages, mechanical breakdowns, and overwhelming Allied firepower. Many had been abandoned by their crews, left beside roads in forests or on the edges of battlefields where they had fought their final engagements.

By the time Germany’s unconditional surrender took effect on the 8th of May 1945, approximately 1,800 Tiger tanks had been produced across both variants. The vast majority had already been destroyed in combat, but several hundred remained, scattered across occupied territories. These survivors faced different fates. Some sat intact in German depots.

Others had been disabled by their own crews to prevent capture. Still others had simply run out of fuel in the war’s chaotic final weeks. At testing grounds like Kumersdorf and Hillers, Allied investigators found Tigers in various states of completion alongside technical documents, spare parts inventories, and training manuals.

In Bavaria, American forces discovered tigers at the Henchel factory facilities. In northern Germany and Austria, British units encountered abandoned heavy tank battalions. On the Eastern front, Soviet armies overran Tiger positions in Silisia, East Prussia, and Czechoslovakia. The variety of conditions surprised Allied tank officers.

Some Tigers appeared nearly pristine, preserved by units that had surrendered intact. Others showed catastrophic damage from internal demolitions. Their turrets blown off by crews determined to deny them to the enemy. Many bore the scars of combat, including penetrated armor, track damage, engine fires, and the marks of anti-tank weapons that had finally stopped them.

Unlike fighters or bombers that could be flown away, Tigers presented an immediate logistical challenge. Each tank weighed over 50 tons. The Tiger 2 even heavier at 70 tons. Moving them required specialized equipment, rail transport, or heavy recovery vehicles. The Allied Control Commission established strict protocols.

All German armored vehicles were to be immobilized immediately, their weapons disabled, and their fuel supplies drained. A debate quickly emerged within Allied commands. Some argued that Tigers should be destroyed as symbols of German military power. Others recognized their intelligence value, particularly their armor composition, optical systems, and the legendary 88 mm gun.

What became clear in the weeks after surrender was that the Tiger’s legend would outlast the tank itself, even as the machines were systematically dismantled or tested to destruction. As Germany surrendered, the Allies launched immediate programs to seize and study Tiger tanks. Each power had faced Tigers in combat and lost tanks to their guns.

Now they had the chance to understand how these machines worked and why they had been so difficult to defeat. The United States moved quickly. American armored units had encountered Tigers in North Africa, Italy, and France, always with respect and often with heavy losses. Intelligence teams from the ordinance department spread across Germany and Austria, locating intact examples for evaluation.

At the Aberdine proving ground in Maryland, engineers prepared facilities to receive captured German armor. One of the first Tiger shipped to America came from North Africa, captured during the Tunisian campaign in 1943. By war’s end, additional examples arrived from Europe. American tests focused on armor penetration, measuring how different anti-tank weapons performed against Tiger Plate at various angles and ranges.

Engineers fired American 75 mm, 76 mm, and 90 mm guns at captured hulls, documenting which rounds could defeat the armor and under what conditions. The results confirmed what tankers already knew. The Tiger’s frontal armor was extremely difficult to penetrate with standard Allied tank guns at combat ranges.

American tests showed that the 75 mm gun equipped on most Sherman tanks could not reliably penetrate a Tiger’s front plate, even at close range. The 76 mm performed better, but still struggled. Only the 90mm gun on late war tanks like the M26 Persing could confidently engage Tigers frontally. The British had their own painful history with Tigers.

From the first encounter in Tunisia to the battles in Normandy, British tank crews had learned to fear the 88 mm gun that could destroy their Cromwells and Churchills at ranges where they could not effectively return fire. At the School of Tank Technology in Chzy and at Lworth, British engineers conducted extensive trials on captured examples.

British tests examined not just armor, but also the Tiger’s mechanical systems. They disassembled engines, transmissions, and suspension units, documenting the sophisticated engineering that made the Tiger formidable, but also mechanically complex. British reports noted the interled road wheel system that provided excellent ride quality, but which was prone to mud and ice accumulation.

They documented the Maybach engine’s power and also its fuel consumption and maintenance demands. At Bobington, a Tiger Y captured in Tunisia became a centerpiece of British evaluation. Test drivers noted the tank’s surprising maneuverability for its size, aided by its advanced steering system. Gunners praised the optical quality of German sights and the accuracy of the 88 mm gun.

However, reports also highlighted reliability issues. the complexity of field repairs and the enormous logistical burden each Tiger represented. The Soviet Union had faced more Tigers than any other Allied power. From Kursk to Berlin, Soviet tank armies had fought desperate battles against heavy tank battalions. Soviet trophy brigades moved systematically across occupied Germany and Eastern Europe, seizing every Tiger they could find.

Intact examples were shipped to testing grounds near Kabinka outside Moscow. Soviet testing was thorough and ruthless. Engineers fired captured German guns at Tigers to understand their vulnerabilities. They tested Soviet 85mm, 100 mm, and 122mm guns against Tiger armor, determining the most effective engagement tactics.

Stalin himself took interest in German heavy tank development, pushing Soviet designers to incorporate lessons learned into new projects like IS-3 and T10 heavy tanks. The Soviets also captured Tigers in unusual circumstances. In Prague, they found examples that had been undergoing repair or modification. In Sisia, entire training facilities fell intact, complete with Tigers used for crew instruction.

Some of these machines were restored to running condition and briefly used for propaganda, demonstrating Soviet mastery over German equipment. Competition emerged among the Allies for the rarest examples. Everyone wanted a late production Tiger 2, which represented the pinnacle of German heavy tank design.

Factories and castle held partially completed holes and turrets. At testing grounds, prototype variants offered insights into development that never reached production. The race to secure these machines reflected growing tensions that would define the Cold War. German tank crews and engineers played complex roles in this process.

Some were detained for interrogation. Others volunteered information in exchange for better treatment or employment. Their technical knowledge helped Allied teams operate and maintain captured Tigers, explaining maintenance procedures, common failure points, and combat tactics. The Allies documented everything: internal layouts, ammunition storage, crew positions, optical systems, and the sophisticated fire control equipment that made the 88 mm gun so deadly.

The variety of Tiger variants discovered also intrigued Allied investigators. While the Tiger 1 had remained relatively consistent throughout production, late war examples showed modifications based on combat experience. Engineers found Tigers with different track designs, modified vision ports, and experimental armor configurations.

The Tiger 2 revealed even more interesting developments with early production models featuring a different turret design than later versions. At Henchel facilities, Allied teams discovered plans for neverbuilt variants, including proposed tank destroyers and recovery vehicles based on the Tiger chassis.

Particularly valuable were the Tigers found with complete documentation. Some units had maintained meticulous maintenance logs recording every mechanical issue, every repair, and every combat engagement. These records provided insights into the Tiger’s operational reality that pure technical specifications could not reveal.

They showed average breakdown rates, typical lifespan of major components, and the enormous spare parts requirements that made Tiger Battalion so difficult to sustain in the field. Allied logistics officers studied these documents carefully, understanding that German armor’s greatest weakness was not its design, but its sustainability.

By late 1946, the major intelligence gathering phase was complete. Dozens of tigers had been tested, measured, and analyzed. Their secrets were documented in thousands of pages of technical reports. These findings influenced the next generation of Allied tank design. From armor schemes to gun power to fire control systems.

But for the vast majority of Tigers that survived the war, a different fate awaited. Systematic destruction. By late 1945, the Allied Control Council issued clear directives. Germany could not retain any armored fighting vehicles. The Tigers that had been preserved for testing represented only a tiny fraction of those that survived the war.

The rest scattered across Europe in various states of repair were marked for elimination. The process varied by location and by the condition of each tank. In Germany itself, disposal sites were established at former military bases and training grounds. Tigers deemed worthless for testing were systematically destroyed. Some were used as targets for Allied gunnery practice, allowing tank crews to train against the armor they had faced in combat.

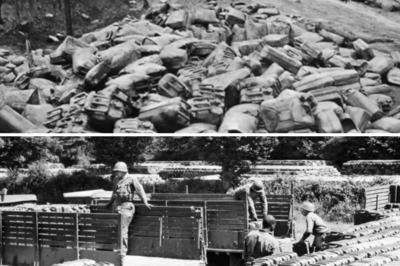

Others were broken up for scrapped metal, their thick armor plates cut with torches and shipped to steel mills. At Bergen Hone in northern Germany, British forces assembled a collection of German armor for destruction. Tigers sat alongside Panthers, self-propelled guns, and other vehicles. Engineers studied the most efficient methods for rendering the tanks unusable, removing guns, draining fluids, disabling engines, or simply demolishing them with explosives.

The turrets of some Tigers were blown off, creating dramatic but permanent destruction. In Normandy, several tigers that had been knocked out during the campaign remained where they fell. Some were buried by local authorities as obstacles were cleared from roads and fields. Others were dragged to collection points and scrapped.

The French army briefly considered retaining some German armor for their own use, but the logistical challenges of maintaining Tigers combined with their enormous fuel consumption made this impractical. The Soviets took a different approach in their occupation zones. While they destroyed many tigers, they also preserved significant numbers for study and display.

Museums in Moscow and Lennengrad received examples for public exhibition, demonstrating Soviet victory over German technology. Some tigers were restored to running condition for propaganda films and military parades, though these were exceptions rather than the rule. Economic factors drove much of the destruction.

Postwar Europe faced severe metal shortages. The thousands of tons of steel, copper, and other materials locked in abandoned German armor represented valuable resources. Scrapping Tigers and other panzers helped supply reconstruction efforts. For many communities recovering from war, the arrival of scrap dealers to dismantle nearby tigers provided employment and income during desperate times.

Environmental considerations also played a role. Abandoned tigers leaked fuel, oil, and other fluids that could contaminate soil and water. Local authorities wanted them removed from farmland, forests, and waterways. In some cases, tigers that had been driven into rivers or lakes during combat were left in place, considered too difficult or expensive to recover.

Many of these underwater wrecks remain today, occasionally discovered by divers or revealed during droughts. By 1948, the vast majority of tigers had ceased to exist. Battlefield wrecks had been scrapped or buried. Depot stocks had been destroyed. The handful preserved in museums or testing facilities represented almost all that remained of the 1,800 tanks produced.

The speed and thoroughess of this elimination reflected Allied determination to permanently dismantle Germany’s military capability. Unlike aircraft, which could be preserved in storage or converted to civilian use, Tigers had no peaceful application. They were purpose-built weapons of war. And in the post-war world, there was no place for them outside of museums and testing grounds.

While most Tigers were destroyed, a small number found their way into foreign service or long-term preservation. These survivors offer insights into how the tanks legend grew, even as the machines themselves disappeared. France retained several captured Tigers for evaluation and training. At Smour, the French tank school used a Tiger Wman to train instructors and to demonstrate German engineering to students.

French engineers studied the 88 mm gun, hoping to incorporate lessons into their own tank destroyer designs. By the early 1950s, maintenance challenges and parts shortages forced France to retire these vehicles. The Somure example survived and remains on display today. Britain kept multiple Tigers for museum purposes and continued testing.

The example at Bobington became one of the most famous surviving tigers, eventually restored to running condition decades later. British technical schools used tigers as teaching aids, allowing students to study German engineering firsthand. When these educational uses ended, several examples entered museum collections rather than being scrapped.

The Soviet Union maintained the largest collection of preserved tigers. Museums across the Soviet block received examples from Moscow to Warsaw to Prague. Some were restored and displayed with combat damage, illustrating Soviet triumph. Others were kept in storage facilities and occasionally brought out for military demonstrations or historical events.

Soviet access to multiple examples allowed for more comprehensive study than the Western Allies could conduct. No country attempted to use Tigers operationally after the war. Their mechanical complexity, fuel consumption, and parts requirements made them impractical for any military force to maintain. Unlike the BF109 or JU52, which saw limited foreign service, Tigers were too specialized and too resource inensive to justify keeping operational.

However, the Tiger’s reputation ensured that scrapping slowed as historical awareness grew. By the 1960s, military historians and museum curators recognized that very few examples had survived. Efforts began to locate battlefield wrecks and recover tanks before they were lost completely. Several tigers were pulled from swamps, forests, and fields across Eastern Europe.

Many were incomplete or badly damaged, but even partial hulls had historical value. The restoration of tigers became a specialized field. Museums like Bobington invested years in bringing their tiger wood to running condition, a project completed in the 1990s. Other institutions focused on static display, stabilizing corroded metal, and preserving what remained.

Private collectors occasionally acquired Tiger components, though complete tanks remained extraordinarily rare and valuable. Today, only a handful of complete Tigers exist worldwide. The Tiger Wine at Bovington is the only example capable of movement, though it runs rarely to preserve the irreplaceable machine.

Other surviving examples sit in museums across Russia, France, Germany, Britain, and the United States. Each represents not just a single tank, but the entire production run of a weapon that defined armored warfare. Several Tiger 2 examples also survive, including the famous tank at L Gleas in Belgium.

This King Tiger was abandoned by its crew during the Battle of the Bulge and remained in the village as a memorial. Others sit at Kubinka, Fort Benning, and various European museums, silent witnesses to the final years of the Third Reich. The scarcity of surviving tigers has made them objects of intense historical interest. Each example is studied, photographed, and measured by researchers hoping to understand details lost when the majority were destroyed.

Rare components from periscopes to radios to ammunition racks are documented whenever discovered. The few tigers that remain have become priceless artifacts, their value immeasurable in historical terms. What survived the immediate postwar destruction phase was essentially random. Tanks that happened to be in the right place, captured by forces inclined to preserve them, or simply overlooked during the rush to scrap everything else were saved.

The systematic elimination of the 1940s means that what exists today represents less than 1% of all tigers produced. Fragments of a legend that grew larger as the machines themselves disappeared. The story of Tigers after 1945 is ultimately one of rapid destruction followed by slow recognition of what had been lost. In their eagerness to dismantle German military power, the Allies eliminated most examples of what would become one of history’s most studied tanks.

By the time historians and museums sought to preserve tigers, very few remained to save. Modern efforts to locate tigers continue. Occasionally, a wreck is discovered in a forest or pulled from a riverbed. Each find generates significant interest, even if the tank is too damaged for restoration.

These discoveries remind us how quickly even the most formidable machines can vanish. And how the post-war world reshaped the legacy of German armor just as it reshaped the legacy of the Luftwaffa. If you found this video insightful, watch what happened to the Panzer Waffa Panther tanks after World War II next. It explores how Germany’s most numerous heavy tank was captured, studied, and scattered across the world in the aftermath of the war.

News

Karen Called Police When I Blocked My Own Drive — Had No Idea I’m the Base Commander She Reported To

6:00 a.m. Saturday morning. I’m standing in my own driveway and slippers holding my coffee when two police cruisers roll…

CH1 The Shell That Melted German Tanks Like Butter — They Called It Witchcraft

The first time it hit, the crew of a Panther tank didn’t even hear the shot. There was a flash,…

CH1 German Pilot Ran Out of Fuel Over Enemy Territory — Then a P-51 Pulled Up Beside Him

March 24th, 1945, 22,000 ft above the German countryside near Castle, Oberloidant France Stigler sat in the cockpit of his…

German Colonel Peiper Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was Doomed

December 16th, 1944. The Arden’s forest. SS Lieutenant Colonel Yokim Piper watches his steel predators, the pride of the Panzer…

I Visited My Dad’s Farm — HOA Guards Blocked Me and Said I’m Banned From His Land!

I’ve handled corporate fraud, billion-dollar disputes, and every kind of liar you can imagine. But nothing prepares you for driving…

My husband’s “work wife” bought the house next door. She just announced she’s pregnant and it’s…

My husband’s work wife just became our neighbor. I stood in my kitchen staring at the moving truck backing up…

End of content

No more pages to load