March 1940, Britain’s accountants were calculating how long the nation could survive, and the numbers told a story more frightening than any German bomb. Admiral Carl Donitz’s yubot were erasing 300,000 tons of merchant shipping from the Atlantic every month. The Royal Navy counted precisely 200 escort vessels to defend convoy routes stretching thousands of miles across hostile waters.

Winston Churchill barely two months into his role as first lord of the Admiral Ty drafted a memo that cut through all naval tradition. We require hulls not sophisticated vessels in 2 years. Hulls in the water now. The obvious solution gleamed in every British naval yard. Destroyers. These vessels represented everything the Royal Navy knew about surface warfare.

36 knots speed, four 4.7 inch guns, quintuple torpedo tubes, enough firepower to engage enemy capital ships. They were engineering masterpieces. They were also financial suicide. Each destroyer consumed £200,000 in 1940 currency, roughly 45 million in modern terms, and demanded 18 months of specialized labor.

Britain’s seven major naval yards could deliver perhaps 30 destroyers annually at maximum production. Meanwhile, merchant vessels were vanishing beneath the waves in real time. May 1940, France was collapsing, the Yuboat threat intensifying. Naval architect William Reed walked into an Admiral T meeting carrying blueprints that caused immediate skepticism.

His proposal wasn’t military in origin. Reed had spent the 1930s designing the Southern Pride class, commercial whailing vessels built for Antarctic waters. Simple, sturdy ships using off-the-shelf steel and techniques any coastal shipyard already mastered. They were slow, cramped, possessed zero aesthetic appeal.

They cost £20,000 each and required 8 months to build. That t-fold cost differential wasn’t accounting. It was revolutionary. For the price of one destroyer, Britain could deploy 10 corvettes. For 18 months required to build three destroyers, British Yards could launch 20 corvettes. Reed’s proposal transformed the question from how do we build the perfect submarine killer? Two, how do we flood the Atlantic with enough vessels that cannot avoid them? Commander George Crey, director of anti-ubmarine warfare, understood immediately. The Royal Navy

didn’t require floating super weapons. It required presence, constant, overwhelming, unavoidable presence. Every convoy needed multiple escorts positioned in layered defensive screens that denied yubot safe attack positions. Destroyers were surgical instruments. The Atlantic demanded a sledgehammer. July 25th, 1940.

While the Battle of Britain raged overhead, the Admiral T placed contracts for 58 corvettes designated the flower class. Named after garden plants, Gladiololis, Bluebell, Campanula, a deliberate acknowledgement of their humble nature. Naval traditionalists argued Britain was sacrificing excellence for quantity. These vessels barely managed 16 knots, half a destroyer’s speed.

They carried a single 4-in gun versus a destroyer’s main battery. Their anti-ubmarine armament consisted of depth charges simply rolled off stern rails. None of that mattered when the alternative was empty ocean and defenseless merchant ships. By September 1940, as monthly shipping losses approached 450,000 tons, the first corvette HMS Gladiololis completed trials.

She looked nothing like a proper warship. She would help save Britain regardless. Admiral Carl Donitz had perfected his tactical doctrine since 1936. Traditional submarine warfare treated each boat as an independent hunter. Donitz developed rud tactic, wolfpack tactics. A lead hubot would shadow a convoy reporting position while sisterboats converged.

When six or eight submarines surrounded their prey, they attacked simultaneously from different bearings, overwhelming escorts through coordination. The mathematics were brutal. A single destroyer could pursue one hubot, perhaps engage a second. But six yubot attacking from six directions meant the escort spent the entire engagement racing between threat axes while merchantmen burned.

The night of October 18th, 1940, convoy SC7 learned this in blood. 43 merchant ships departed Sydney, Nova Scotia, protected by two escorts. Five Ubot found them south of Iceland. By dawn, 21 ships had been torpedoed. The escorts never had a chance. They couldn’t be in six places simultaneously.

Churchill understood the geometry perfectly. In his first major address as prime minister, he coined the phrase battle of the Atlantic. The only campaign he admitted genuinely terrified him throughout the war. Britain imported 55 million tons of supplies annually. Lose that lifeline and military resistance became irrelevant.

the nation would starve or surrender within months. The Royal Navy counted 200 escort vessels. In September 1939, Donits commanded 57 Yubot with production ramping toward 30 per month. The Corvette solution didn’t defeat Wolfpacks through superior capability. It defeated them through ubiquity. Donit’s tactics relied on escorts being outnumbered.

What happened when convoys suddenly carried not two escorts but 8 1012? The arithmetic inverted. When a wolfpack formed around convoy ns27 in September 1941, they encountered HMS Gladiolus, Bluebell, Campanula, Nastersium, and four additional corvettes forming a protective ring. When Ubot attempted coordinating surface attacks, corvettes were everywhere, forcing submarines underwater where they lost speed and coordination.

The pack scattered. This represented a philosophical revolution in naval warfare. For centuries, British doctrine emphasized individual ship superiority. Build better vessels, defeat them in single combat. The Corvette embraced opposite thinking. build adequate vessels in overwhelming numbers, win through saturation.

It was profoundly unbritish, almost industrial in its cold logic. Senior officers hated it. Admiral Dudley Pound called early Corvettes scarcely fit for purpose. Individually, they weren’t. Collectively, they became unstoppable. Between October 1940 and March 1941, 30 corvettes entered service. Monthly merchant losses actually increased.

The happy time for Yuboat crews. But the trend line was shifting. Every new Corvette narrowed the escort gap. By May 1941, 89 corvettes prowled the Atlantic and average convoy escort strength had tripled. Yubot still found targets, but coordinating attacks grew exponentially harder. The cheap fishing boats were hunting back.

The blueprints Smith’s Dock Company unrolled in August 1940 showed a vessel 205 ft long with a 33 foot beam. Dimensions lifted almost directly from Southern Pride Whailing ships. Naval constructor William Reed hadn’t designed a warship. He’d taken a proven commercial hull, stripped the whale processing equipment, bolted on military fittings.

The Admiral T specification was deliberately primitive, reciprocating steam engines instead of modern turbines, riveted construction instead of welded single screw propeller. Every choice prioritized one criterion. Any shipyard in Britain must be able to build these using existing skills. This proved transformative.

Destroyer construction required specialized yards with heavy slipways. Precision engineering workshops, workforce teams trained to naval standards. Only seven British yards possessed these capabilities. Corvettes needed none of it. Smith’s Dock in Middlesborough, Hall Russell in Abedine, Harland and Wolf in Belfast. Even small commercial yards that built coastal freighters received contracts.

The flowerclass design specified commercial-grade steel plating, standard merchant ship rivets, components already in mass production. Reed later admitted he intentionally dumbed down the design so a yard building fishing trollers could transition to corvettes within weeks. The engine choice illustrated this perfectly.

Destroyers mounted Parsons geared turbines generating 40,000 shaft horsepower. spectacular machinery requiring specialist foundaries and 9 months manufacturing time. Corvettes received triple expansion reciprocating engines producing 2,750 horsepower. Victorian technology essentially scaled up railway locomotive mechanisms.

Britain manufactured them by the hundreds for merchant ships, tugboats, industrial applications. They were sitting on warehouse shelves ready for immediate installation. Construction speed reflected these compromises. A John Crown and Suns in Sunderland Corvette hulls took shape using techniques unchanged since Victorian times.

Riveters worked in fourman teams, heating rivets cherry red, driving them through holes, flattening with pneumatic hammers. The process was noisy, labor intensive, desperately slow by modern standards. Yet Crown’s workforce already knew these methods intimately. November 12th, 1940, they laid HMS Campula’s keel. June 3rd, 1941, just under 7 months later, she completed sea trials.

Compare that to HMS Jervis, a Jclass destroyer laid down at Hawthorne Leslie in August 1937. Her construction required precision matched turbine components from three factories, custom electrical systems, fire control equipment built to thousandth of an inch. She commissioned May 1939, 21 months later, representing 300,000 man-h hours of highly skilled labor.

Jervis was undeniably superior in every category. She was also one ship. In those 21 months, British Yards completed 47 corvettes using the same labor hours distributed across less skilled workers. Smith’s Dock alone eventually built 42 flowerclass corvettes, launching one every 17 days at peak production.

The Admiral T had consciously sacrificed perfection for volume, betting Britain’s survival on whether quantity could substitute for quality. The destroyer HMS Electra, commissioned February 1939, represented everything the Royal Navy understood about modern warfare. Steam turbines drove her to 36 knots. Eight 4.

7 inch guns provided overwhelming firepower. Her Azdic could detect submarines at 1,500 yd. Electra cost £25,000 and consumed 18 months of labor. She was magnificent, genuinely capable of dominating any tactical situation. February 27th, 1942. Japanese destroyers sank Electra during the Battle of the Java Sea. Britain lost 205,000 pounds and 18 months of irreplaceable construction capacity in 7 minutes of combat.

HMS Glowworm, HMS Hardy, HMS Hostile, destroyers worth nearly £650,000 combined were gone by June 1940. The Royal Navy began the war with 184 destroyers. By December 1940, 35 had been sunk or damaged beyond repair. Each loss represented enormous sunk costs that couldn’t be recovered. Corvettes reversed this equation brutally.

HMS Gladiololis cost £20,000 onetenth destroyer price when U568 torpedoed her October 16th 1941 Britain lost a ship not an irreplaceable asset. 7 weeks later Smith’s dock launched HMS Helotrope to replace her. The entire cycle took less time than building one destroyer. This economic resilience mattered enormously.

The Battle of the Atlantic would destroy 47 corvettes between 1940 and 1945. Replacing them cost 940,000 total. Replacing 47 destroyers would have consumed 9.6 million and monopolized British shipyards for three solid years. The time factor cut even deeper. September 1940. Monthly merchant losses exceeded 450,000 tons.

Britain needed escorts immediately deployed. Camel le began HMS Opportune a destroyer in July 1940. She wouldn’t commission until August 1942, 25 months later. During those same 25 months, British Yards completed 127 corvettes. Every hull could escort convoys, hunt submarines, deny Dunit the empty ocean his wolfpacks required. Opportune was superior to any corvette.

She was unavailable when Britain needed her most. Strategic planners faced this constantly. Resources for one destroyer could produce 10 corvettes. Did 10 adequate ships provide more value than one excellent ship? The Atlantic answered yes. Convoy defense wasn’t about winning individual engagements. It was about denying Yubot’s attacking opportunities.

A destroyer could sprint to one threatened sector at 36 knots. Engage brilliantly, defeat the threat. Three other sectors remained undefended. 10 corvettes could form overlapping zones that prevented yubot from reaching attack positions at all. Admiral Percy Noble, Commanderin-Chief Western Approaches, quantified this December 1941.

His command required minimum 300 escort vessels for adequate convoy protection. At destroyer production rates, reaching that strength would require 8 years. At corvette rates, 18 months, Britain had nearly achieved it. The fast destroyer remained tactically superior. Strategically, it was irrelevant. Wars aren’t won by perfect weapons that arrive too late.

They’re won by adequate weapons available when needed. Aboard HMS Gladiololis, November 1940. Able Seaman Ronald Rundle learned why veteran crews called corvettes halfway to hell ships. The vessel rolled 40° to port, paused, crashed 40° to starboard, completing the cycle every 8 seconds. This wasn’t dramatic weather. This was Tuesday morning in 46 winds conditions the North Atlantic produced three days per week.

Rundle with twothirds of the crew spent that watch vomiting. The remaining third had stopped eating. The rolling stemmed from design compromises. Corvettes adapted from whailing ships had a 6:1 lengthto-beam ratio, short and round. This made them incredibly seaorthy, nearly impossible to sink through weather. It also made them roll violently in any seaate above flat calm.

Destroyers sliced through waves. Corvettes rode over them, corkcrewing through every axis. Living spaces made it worse. Gladiololis’ 85 men shared accommodations designed for 47. The forward mess housed 40 ratings in a compartment 30 ft by 20 ft. When Atlantic swells exceeded 15 ft, seaater came through ventilation shafts.

Clothing never dried. Mold grew on everything. Lieutenant Commander Henry Chesterman reported 60% of his crew suffered from saltwater boils. Infections from wet wool uniforms rubbing skin. The cold was equally relentless. Corvettes lacked proper heating. Small coal stoves provided warmth, but officers banned their use during yubot alerts because smoke created visible signatures.

Men stood 4-hour watches where winter temperatures hovered near freezing. Frostbite cases were routine. January 1942, HMS Blue Bell’s medical officer treated 12 frostbite injuries during a single crossing. Speed created tactical nightmares. Corvette engines pushed them to 16 knots maximum in calm seas. In typical swells, 12 knots.

Ubot surfaced managed 17 knots. This meant corvettes couldn’t catch submarines on the surface. They could only force them to dive then pursue with depth charges. Commander Donald McIntyre watched helplessly as Hubot shadowed his convoy just beyond effective range. His corvettes plotted along, unable to pursue, crews exhausted, soaked, freezing.

Yet these miserable vessels performed. Throughout 1941, Corvettes spent more days at sea than any other vessel class, averaging 240 days annually versus 180 for destroyers. They couldn’t run down yubot, so they stayed at sea longer, maintaining constant presence. Crews functioned while perpetually seasick, sleeping in wet clothing, standing watch in conditions that destroyed morale aboard comfortable ships. Those men saved Britain anyway.

HMS Gladiololis claimed her first kill March 16th, 1941, U47, commanded by the legendary GA Prienne, who penetrated Scarpa Flow in 1939 and sank HMS Royal Oak. Pin was stalking convoy OB293 southwest of Iceland. Gladiololis detected him on Azdic at 1,400 yards. Closed despite heavy seas, rolled 14 depth charges in a diamond pattern.

U47’s hull imploded at 180 ft depth, taking prien and 45 crew. Germany lost one of its most celebrated aces. Britain lost depth charges costing £8 each. The statistics accumulated. HMS Bluebell sank U651 in June 1941. Campula destroyed U74 that May. Narcissus accounted for U568 in October. By December 1941, corvettes had sunk 19 confirmed Yubot, more than all British destroyers combined during the same period.

The disparity wasn’t tactical superiority. It was operational mathematics. Destroyers spent 60% of their time in port. Corvettes with simple reciprocating engines remained at sea 70% of the time. More sea time meant more encounters. More encounters meant more kills. The engagement pattern became predictable. Hubot detected on the surface would dive immediately upon sighting corvettes.

Once submerged, Yubot lost their 17 knots surface speed, crawling at seven knots. Corvettes now held speed advantage. They’d quarter the area systematically, pinging with Azdic, forcing submarines to remain submerged and burn battery power. Eventually, the Yubot either surfaced into gunfire or stayed down until depth charges found it.

Commander Peter Gretton described it as terrier tactics. We couldn’t outrun them, so we outstayed them. HMS Gladiololis herself fell October 16th, 1941. Torpedoed by U568 south of Iceland, she sank in 4 minutes, taking 80 of 85 crew. Between 1940 and 1945, 47 Flowerclass corvettes were destroyed. Each loss killed an average of 65 men. Yet Britain kept building replacements faster than Ubot could sink them.

The final accounting published by the Admiral T in 1946. Flowerclass corvettes participated in actions that destroyed 294 Ubot. 47 solo kills, 247 shared. No other Allied warship class came close. Destroyers sank 174 Yubot total. Frigots accounted for 187. Aircraft claimed 386, but corvettes held second place despite being the least capable vessel type.

Technically, the exchange rate was strategically decisive. Britain lost 47 corvettes worth £940,000 combined. Those vessels helped destroy 294 Ubot worth approximately 16 million pounds. Each type 7 yubot cost 55,000 to build. Germany also lost 15,000 trained submariners. Irreplaceable specialists requiring 9 months training.

Dunit’s force never recovered. The slow, humble corvette had killed Germany’s submarine arm through being numerous enough and persistent enough that superior German boats couldn’t avoid them. Quantity achieved what quality never could. The final invoice arrived at the Treasury August 1946. 267 Flowerclass Corvettes at £20,000 each, plus 151 castle class variants averaging £31,000 totaled £10.1 million, 2.

8% of Britain’s total wartime naval expenditure. For that modest sum, the Royal Navy acquired vessels that held the Atlantic lifeline open long enough for American industrial might to tip the balance. Consider the alternative. Suppose Britain had pursued a destroyerbased escort strategy. Each convoy required minimum eight escorts.

Britain ran approximately 300 convoys annually between 1940 and 1945. Maintaining those groups required roughly 3,000 destroyers at £200,000 per destroyer. That would have cost600 million pounds, 60 times actual corvette expenditure. Where did that 590 million pound savings go? Operation Overlord cost Britain 190 million.

The Mediterranean campaign consumed 140 million. Strategic bombing operations required 15 million. These three operations, the strategic efforts that defeated Germany, cost45 million pounds combined. The corvette program savings nearly covered all three simultaneously. By choosing adequate ships over perfect ships, Britain retained sufficient industrial capacity to fight on multiple fronts rather than bankrupting itself, protecting a single maritime corridor.

Monthly merchant losses peaked at 768,000 tons in November 1942 when donuts nearly severed the Atlantic lifeline. By May 1943, losses had collapsed to 264,000 tons while Ubot sinkings spiked to 41 that month. Donit withdrew his Wolfpacks May 24th, 1943, admitting he could no longer sustain losses. June 1st, 1943, Western Approaches Command counted 187 corvettes in operational service versus 94 destroyers.

Those corvettes provided the numerical density that transformed convoy defense from desperate scrambling to systematic coverage. No convoys sailed unescorted after mid 1941. Most carried eight or more escorts. By 1943, Yubot faced overlapping Azdic screens, coordinated depth charge patterns, tactical groups that outnumbered attacking Wolfpacks.

The true cost comparison wasn’t £20,000 versus £200,000 per hull. It was £10.1 million buying strategic victory versus 600 million buying bankruptcy. Britain entered the war as the world’s largest creditor nation and emerged as its largest debtor. Adding another 590 million pounds for destroyers would have rendered the debt unsustainable, likely forcing compromised peace in 1943 when American aid came with stringent conditions.

The Corvette program, derided by traditionalists as unseemly, purchased something beyond price. Britain’s continued participation in the war threw to unconditional victory. The humble flowerclass vessels with their civilian origins and commercialgrade construction saved not just convoys but Britain’s capacity to remain in the fight.

That’s worth substantially more than any destroyer ever built.

News

CH1 “EVERY SONG IS A STORY” — TAYLOR SWIFT JUST SHOOK ALL OF HOLLYWOOD THE $100 MILLION ALBUM THAT COULD CHANGE EVERYTHING

Hollywood has survived scandals, buried accusations, and patched over countless “quiet settlements”… but nothing in the last decade has…

CH1 German POWs Laughed at U.S. Cafeterias — Until They Lined Up for Seconds

The war had ended in Europe, but the prisoners carried their pride with them across the Atlantic. In June 1945,…

CH1 German Officers Smirked at American Rations, Until They Tasted the Army That Never Starved

December 17th, 1944. The frozen earth of the Arden’s forest crunched beneath Vermach boots as German officers surveyed their latest…

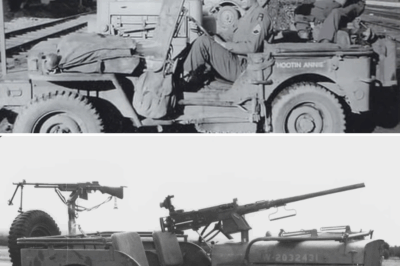

CH1 How the American Jeep Shocked the Germans on D-Day

June 7th, 1944, near smellers Normandy, Oberator, Klaus Miller of the 709th Infantry Division stared in disbelief at the column…

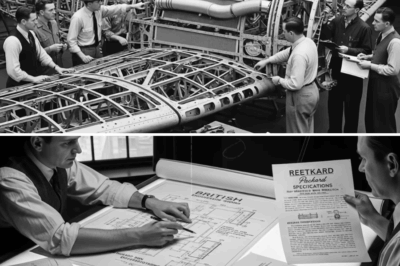

CH1 THE P-51’S SECRET: HOW PACKARD ENGINEERS AMERICANIZED BRITAIN’S MERLIN ENGINE

August 2nd, 1941, Detroit, Michigan. Inside Packard Motorcar Company’s East Grand Boulevard plant, two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines roared to life…

HOA Called Cops When I Moved Out of the HOA — Lost It When She Learned I Bought the Entire Block

She dialed 911 the moment I packed my first box. “He’s abandoning the rules,” she shrieked into her phone, her…

End of content

No more pages to load