How did a school prank send everyone straight to the ER? The whole thing started because Jay wanted to be a legend before spring break. He’d been planning something big for weeks, dropping hints in our group chat about how this would be the prank everyone remembered forever. I didn’t think much of it at first since Jay talked big about everything from his gaming skills to his non-existent dating life, but then he showed me and Devon the YouTube video during lunch on a Wednesday, and I realized he was actually serious about

going through with this insane plan. The video was titled Epic Stink Bomb Prank: School Evacuation and had over 340,000 views. Some kid in a different state had mixed household chemicals in a bottle and hidden it in the boy’s bathroom, making the whole wing smell so bad they had to evacuate.

Jay kept rewinding to the part where students were gagging and running out of the building, laughing so hard he could barely breathe. He said we could do it even better by putting it in the ventilation system so the whole school would smell it at once. Devon thought it was hilarious and started suggesting locations, but something about the comment section made me uncomfortable. There were warnings mixed in with the jokes.

People saying, “Don’t try this and this is actually dangerous.” But those comments had way fewer likes than the ones saying, “Legend, and I’m doing this at my school.” That night, Jay texted our group chat with a shopping list of ingredients. He’d screenshot the video description where the original prankster listed everything needed.

Household ammonia cleaner, sulfur powder from a garden store, and some other chemicals I’d never heard of. The measurements were listed in teaspoons and tablespoons, like it was a recipe for cookies instead of something that could clear out a building. Devon immediately volunteered to get the ammonia since his mom had industrial strength cleaning supplies in their garage.

Jay said he’d order the sulfur powder online with his brother’s Amazon account, claiming it was for a science project. They kept tagging me in the chat asking what I’d contribute, but I just sent back a thumbs up emoji without committing to anything specific. My gut was telling me this was a terrible idea, but I didn’t want to be the one who killed the vibe by being paranoid. Looking back, that was the moment I should have said something.

Should have told them to watch a different video or pick a harmless prank like filling the principal’s office with balloons. Instead, I stayed quiet and let Jay’s excitement steamroll over my doubts, convincing myself that if the prank had 340,000 views, it couldn’t be that dangerous. The sulfur powder arrived at Jay’s house 5 days later in a plain brown package.

He brought it to school in his backpack on Friday, showing it off to our lunch table like he’d just scored tickets to a soldout concert. The container was smaller than I expected, maybe the size of a spice jar filled with yellow powder that looked completely harmless. Jay kept the video pulled up on his phone, checking and re-checking the measurements, even though he’d probably watched it a hundred times by then.

Devon had stolen a 2 L bottle from the recycling bin at his house and cleaned it out in the bathroom sink. They were planning to mix everything that afternoon in the chemistry storage room during sixth period when Mr. Patterson always left to make copies. I watched them discuss their plan in excited whispers, passing the phone back and forth to replay certain parts of the video.

The original prankster had mixed his concoction outside in his backyard, but Jay insisted we needed to do it indoors so nobody would see us. He’d scoped out the storage room earlier that week and found it unlocked during sixth period every single day. The plan was simple.

Mix the chemicals, seal the bottle, plant it in the air conditioning vent above the cafeteria during lunch on Monday, and let the ventilation system do the rest. Monday morning felt different from the moment I walked into school. Jay was practically vibrating with nervous energy, checking his phone every few seconds, even though we didn’t have any new messages.

The bottle was in his locker already mixed and sealed from Friday afternoon when they had done it without me. I’d made an excuse about having to make up a test, which was partly true, but really I just didn’t want to be there when they combined those chemicals. During second period English, my phone buzzed with a message from Devon saying, “It’s done. Bottles in the vent. Going to be epic.

” My stomach did a weird flip as I stared at those words, realizing there was no taking it back now. Whatever was about to happen would happen, and all I could do was hope Jay had followed the measurements exactly right. Mrs. Bun Sheffield was reading from The Great Gatsby when the fire alarm started blaring around 10:47.

Everyone groaned because we just had a drill last week, but then the intercom crackled and Principal Morrison’s voice came through sounding strained and urgent. He said, “This wasn’t a drill and we needed to evacuate immediately using our designated routes.” The tone in his voice made everyone stop complaining and actually move quickly toward the exits.

Outside on the field, clusters of students were pointing back at the building and pulling out their phones to record. Nothing looked wrong from the outside. No smoke or flames, just the normal brick facade of Jefferson High on a sunny spring morning. Teachers were trying to take attendance while students kept asking what was happening and whether this was part of Jay’s prank.

I found Devon in the crowd and he grabbed my arm, his face pale under his usual tan. He said something was wrong because the smell was supposed to be bad but not dangerous. Just enough to get school canceled for the day. But then he’d seen kids stumbling out of the east entrance, holding their throats and coughing so hard they were doubled over.

Three girls from our biology class were sitting on the curb with their heads between their knees while a teacher fanned them with a folder. Devon kept asking where Jay was, scanning the crowd with increasingly panicked eyes. I hadn’t seen Jay since third period when he’d given me a thumbs up in the hallway, grinning like everything was going exactly according to plan.

The crowd kept growing as more classes filed out and teachers started counting heads obsessively, checking names off their rosters. That’s when the first ambulance showed up with lights flashing, pulling right up onto the grass near the main entrance. The paramedics jumped out and rushed inside with their equipment bags while we all stood there watching.

Then another ambulance arrived and another until there were six of them parked at crazy angles on the lawn. Students who’d been near the cafeteria during third period were being pulled aside and checked by EMTs with stethoscopes and oxygen masks. One kid I recognized from math class was on a stretcher being wheeled toward an ambulance, his face covered with an oxygen mask and his eyes closed.

The teacher started hurting us further away from the building, pushing us back toward the football field while more emergency vehicles arrived. Fire trucks, police cars, and a white van with hazmat response unit printed on the side in blocky letters. Men in yellow protective suits started carrying equipment into the school. And that’s when I knew this was way worse than just a bad smell.

My phone started blowing up with texts from my mom asking if I was okay because the news was reporting a chemical incident at Jefferson High. I tried to text back that I was fine, but my hands were shaking so bad I could barely type. Devon had disappeared into the crowd somewhere, and I still couldn’t find Jay anywhere in the sea of students covering nearly 2 acres of field space.

Principal Morrison came back outside around 11:30 and gathered us all together using a megaphone. His voice was shaky as he announced that multiple students had been transported to the hospital with respiratory distress and that the building was being evacuated due to a hazardous chemical exposure. He kept saying the situation was under control and that paramedics were treating anyone who felt sick, but his face told a different story.

Behind him, I could see more students being led out of the building by people in protective suits, some walking on their own and others being supported between two adults. A girl from the drama club collapsed halfway across the parking lot and EMTs rushed over with a stretcher. The crowd got quieter as we all watched her get loaded into an ambulance. The reality of what was happening finally sinking in through the initial excitement. This wasn’t a funny prank story we’d tell later.

This was an actual emergency with real ambulances and real injuries. Parents started showing up in a steady stream of cars, pulling up to the barriers police had set up and demanding to get their kids. Teachers were calling out names and sending students to the parking lot in small groups, checking them off lists and making sure everyone was accounted for.

I finally spotted Jay standing by himself near the equipment shed, staring at the chaos with this blank expression on his face. I pushed through the crowd to get to him and grabbed his shoulder, asking what the hell had happened because this wasn’t supposed to be dangerous. He just kept shaking his head and saying he followed the recipe exactly. Measured everything twice.

Did it just like the video showed. His voice was getting higher and faster as he talked, explaining how the video had 340,000 views, so obviously it was safe. People did this prank all the time and nobody got seriously hurt. I asked him if he’d read the comments. Really read them. Not just the funny ones, but the warnings people had posted.

He finally looked at me and I could see tears starting in his eyes. He said he thought those people were just being dramatic, trying to scare others so they wouldn’t copy the prank. The measurements had seemed straightforward when he was mixing everything in the storage room, pouring liquids and powder into the 2 L bottle.

Everything had combined smoothly without any weird reactions or explosions, just created this cloudy mixture that smelled awful, but not dangerously so. He’d sealed the bottle and hidden it in his backpack until lunch, then slipped it into the vent above the cafeteria like they’d planned. A police officer started walking toward us, and Jay’s whole body went rigid.

The officer asked if we were Jay Whitmore, and I had to admit, I didn’t know Jay’s last name, even though we’d been friends for 2 years. The officer checked his notepad and asked which of us was Jay. Looking between our faces, Jay raised his hand like we were in class, his voice barely a whisper as he identified himself. The officer said he needed to come with him to answer some questions about the incident.

Nothing formal yet, just trying to understand what happened. Jay’s face went from pale to gray as he followed the officer toward the parking lot where several police cars were parked. He looked back at me once with this desperate expression, and I wanted to say something helpful or reassuring, but no words came out.

I just stood there watching my friend walk away, knowing he’d wanted to be a legend and instead had created a disaster. Devon appeared next to me and asked what was going to happen to Jay, whether he’d get arrested or expelled or both. I told him I had no idea, but probably nothing good given the number of ambulances still parked on the lawn with more students being evaluated. My mom picked me up around noon and immediately started crying when she saw me walking toward the car.

She’d been watching the news coverage for the past hour, seeing reports of students collapsing and chemical exposure, imagining the worst. I assured her I was fine, that I’d been in a different part of the building when it happened, which was true enough.

She kept asking questions about what chemical it was and who did this and whether the school had been safe. Questions I couldn’t answer because I barely understood what was happening myself. On the drive home, I pulled up the news on my phone and saw Jefferson High trending on Twitter with videos from students showing the evacuation.

One video had gotten over 50,000 retweets already, showing a line of students on stretchers being loaded into ambulances. The comments were full of people asking what happened and others sharing conspiracy theories about terrorism or gas leaks. Nobody had connected it to a prank yet, which meant Jay might have a few more hours before his name got dragged through social media.

My phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number that turned out to be Jay asking me not to say anything to anyone about the prank. He said the police were calling his parents and he was probably going to be in serious trouble, but if nobody else knew about the planning, maybe it would seem like an accident.

That night, the local news led with our story showing aerial footage of Jefferson High surrounded by emergency vehicles. The anchor said 47 students had been transported to area hospitals with symptoms including difficulty breathing, dizziness, nausea, and loss of consciousness. 12 students were in serious condition, three were in the ICU, and one 17-year-old was in a medicallyinduced coma.

My stomach turned as those numbers scrolled across the screen with somber music playing underneath. The reporter said authorities were investigating the source of the chemical exposure, which they’d identified as hydrogen sulfide gas. The name meant nothing to me, but they explained it was a toxic gas that could cause respiratory failure and death at high concentrations.

They showed interviews with parents crying outside the hospital, talking about their kids struggling to breathe and vomiting blood. One mother said her son had been perfectly healthy that morning, and now doctors weren’t sure if he’d have permanent lung damage. The news switched to an interview with someone from the fire department’s hazmat unit, who explained that hydrogen sulfide was heavier than air, so it had sunk through the ventilation system and pulled in lower areas of the building.

The cafeteria on the first floor had gotten the highest concentration, which explained why students who’d been there during third period lunch were the worst affected. I couldn’t sleep that night. Kept checking my phone for updates about the students in the hospital. Social media was exploding with speculation about what caused the gas leak, with some people claiming the school’s boiler malfunctioned, while others thought it was a terrorist attack. Nobody was talking about pranks yet, which felt like a countdown to an inevitable explosion when the truth came out.

Around midnight, Devon called me crying and asking if we were going to jail because he’d provided the ammonia. I tried to calm him down, saying we didn’t actually mix anything or plant the bottle, but my words sounded hollow even to my own ears.

We’d known about the plan, had seen the ingredients, had opportunities to stop it, and chosen not to. That made us something, even if we weren’t the ones who’d physically done it. Devon kept saying his parents were going to kill him if they found out that his dad was a lawyer and would disown him for being involved in something this stupid. I told him to delete any texts or messages related to the prank, though I wasn’t sure if that would help or make things worse.

After we hung up, I sat there staring at our group chat, reading through weeks of messages about the prank planning. My finger hovered over the delete button, but I couldn’t make myself press it. Tuesday morning, Jefferson High was still closed for decontamination while investigators tried to determine exactly what had happened.

My parents made me stay home, even though I felt fine, worried I might develop delayed symptoms from whatever exposure I’d had. The news showed footage of people in hazmat suits going in and out of the school building, carrying equipment, and taking samples. A press conference was scheduled for 10:00 a.m. with school officials and the police department.

I watched it on my laptop with my stomach in knots, knowing this was probably when everything would come out. Principal Morrison stood at a podium looking like he’d aged 10 years overnight, reading a prepared statement about the incident. He said investigators had determined the hydrogen sulfide gas came from a chemical mixture deliberately placed in the school’s ventilation system. He used the word deliberately twice, making it clear this wasn’t an accident.

Then the police chief stepped up and announced they’d arrested a 17-year-old male student in connection with the incident. He wouldn’t give the name because of the student’s age, but said charges included reckless endangerment, assault with a deadly weapon, and creation of a catastrophic risk. My phone started ringing immediately with calls from numbers I didn’t recognize.

I let them all go to voicemail and listened as reporters left messages asking if I knew Jay Whitmore and whether I’d talk about what happened. Someone had leaked his name to the media, and now it was spreading across every platform. By noon, Jay’s Instagram and Facebook profiles were being screenshotted and shared.

His face appearing on news sites under headlines like teen arrested for chemical attack on high school and students prank lands classmates in ICU. The comment sections were brutal. Thousands of people calling him a terrorist and saying he deserved life in prison. Someone found his YouTube channel where he’d posted gaming videos and flooded it with hate comments.

His subscriber count was rising rapidly, but not for any reason he’d ever wanted. I felt sick watching his digital life get torn apart in real time by strangers who knew nothing about him except this one terrible decision. The news kept updating the victim count throughout the day and by evening it had reached 53 students with confirmed hydrogen sulfide exposure.

The boy in the medically induced coma was identified as Nathan Cross, a junior on the wrestling team who’d been sitting in the cafeteria when the gas started filling the room. On Wednesday, I got called out of my room by a knock on the front door. My dad answered and came to get me, saying there were detectives who wanted to ask me some questions.

My heart started pounding as I walked to the living room where two people in plain clothes were waiting. A man and a woman who introduced themselves as Detective Mills and Detective Park. They asked if I knew Jay Whitmore and whether I’d had any conversations with him about pranks or chemicals in the days before the incident.

I told them we were friends and hung out sometimes, trying to keep my voice steady even though my hands were shaking. Detective Mills pulled out a printed copy of our group chat, and my stomach dropped when I saw messages I’d written highlighted in yellow. They walked me through the conversation where Jay had shared the YouTube video, asking what I thought he meant by certain messages.

I tried to explain that we thought it was just a harmless prank, that nobody understood how dangerous it actually was, but the words sounded pathetic out loud. Detective Park asked if I’d seen Jay mixing the chemicals or helped him obtain any of the ingredients. I said no truthfully, explaining that I’d skipped the mixing part because I had to make up a test.

She wrote something in her notebook and exchanged a look with Detective Mills that I couldn’t read. They asked about Devon next, whether he’d been involved in planning or execution. I felt trapped between protecting my friend and not lying to police. So, I said Devon had talked about the prank, but I didn’t know specifics about what he did. Detective Mills leaned forward and said they already knew about Devon’s involvement because they’d pulled phone records and found text messages where he discussed providing supplies. He said Devon had been smart enough to cooperate immediately and provide a full statement

about what happened. My mouth went dry as I realized Devon had already told them everything, which meant lying would only make my situation worse. I admitted that Devon had mentioned getting ammonia from his garage and that Jay had ordered sulfur powder online.

Detective Park asked why I didn’t report the plan to a teacher or administrator if I knew chemicals were being brought to school. I tried to explain that it seemed like a joke that people did prank videos all the time, and this one had hundreds of thousands of views, so it must be safe. The words sounded incredibly stupid even as I said them, and Detective Mills’s expression made it clear he agreed.

They asked me to write out a formal statement about everything I knew, and I spent the next hour at my kitchen table writing down dates and conversations while my parents watched with disappointed faces. That afternoon, the news reported that a second student had been arrested in connection with the chemical incident. They didn’t name him, but I knew it was Devon based on the timing.

My phone started buzzing with messages from classmates asking if I was going to get arrested too, if I’d been part of Jay’s plan. I didn’t respond to any of them, just watched the messages pile up while I tried to figure out what was going to happen to me.

My dad sat down and asked me directly whether I’d helped plan this attack, using that word attack like I was a terrorist. I told him the truth, that I’d known about the prank and seen the video, but hadn’t mixed chemicals or planted anything. He asked why I didn’t stop them, why I didn’t tell an adult, and I had no good answer. I’d thought it would be funny. Had wanted to see what happened. Had been too scared of seeming uncool to speak up.

Now three kids were in the ICU and I was being questioned by detectives and all because I’d kept quiet. My mom started crying and said she’d raised me better than this. That staying silent while people got hurt made me almost as guilty as the ones who did it. Her words hit harder than any punishment because I knew she was right. Thursday brought worse news.

Nathan Cross, the wrestler in the medicallyinduced coma, had been taken off sedation but wasn’t waking up properly. Doctors said the hydrogen sulfide exposure had caused his brain to swell from oxygen deprivation and they weren’t sure what his neurological outcome would be.

His parents gave a press conference begging other students to come forward with information about who was responsible. His mother’s face was destroyed by crying. Mascara streaked down her cheeks as she talked about her son who’d just gotten accepted to college on a wrestling scholarship. She said he’d been planning to study engineering and now they didn’t know if he’d ever wake up completely.

The camera showed Nathan’s wrestling photo, a kid with a bright smile and confident eyes who looked nothing like the motionless figure I’d seen being loaded into an ambulance. The press conference ended with his father saying he hoped whoever did this would rot in prison for stealing his son’s future. Comments flooded social media agreeing with him, calling for maximum sentences and adult charges for everyone involved.

Someone started a petition to try Jay as an adult that got 50,000 signatures in 6 hours. That same day, reporters found the original YouTube video that Jay had used for instructions. The channel owner, a kid named Dylan from Wisconsin, had already deleted the video and posted an apology, saying he never meant for anyone to get seriously hurt.

He claimed his prank had only affected one bathroom and cleared out quickly, that he’d used much smaller amounts of each chemical, but internet sleuths had saved copies of the original video and were analyzing it frame by frame, pointing out that Dylan’s measurements were different from the ones he’d listed in the description.

Someone with a chemistry background explained in a long Twitter thread that switching from teaspoons to tablespoons would increase the concentration 10-fold and that mixing it in a closed indoor space would allow the gas to reach lethal levels. The thread went viral with over 100,000 retweets. And suddenly, everyone understood that Jay hadn’t just copied a prank, he’d accidentally created a chemical weapon.

The news picked up the story and started running segments about dangerous prank videos and the responsibility of content creators. Dylan’s YouTube channel got brigaded with hate comments and dislikes until he deleted his entire account. But the damage was done.

The video had been copied and re-uploaded to dozens of other channels where kids could still find the instructions. On Friday, exactly one week after the incident, I got served with papers saying I was being called to testify before a grand jury. My parents hired a lawyer, a serious woman named Rachel Gordon, who specialized in criminal defense.

She explained that being subpoenaed didn’t mean I was being charged, but that I needed to be very careful about what I said because prosecutors were building their case against Jay and possibly Devon. She asked me to go through every interaction I’d had with them about the prank, every text message and conversation and shared video. We spent 3 hours in her office while she took notes and occasionally stopped me to ask clarifying questions.

When I finished, she leaned back in her chair and said I was in a complicated position because I’d known about the plan but hadn’t participated directly. She said prosecutors might offer me immunity in exchange for testifying against Jay and Devon, but that decision would depend on how cooperative I was and whether they believed I’d been a co-conspirator.

The word co-conspirator made my blood run cold because it sounded like something from a crime show, not something that could apply to me for just watching a YouTube video with friends. That weekend, more details emerged about the hydrogen sulfide gas and why it had been so dangerous.

A chemistry professor gave an interview explaining that hydrogen sulfide shuts down the part of your brain that detects smell after just a few breaths, which meant victims couldn’t tell they were being poisoned until it was too late. She said at high concentrations, it could cause something called knockdown, where people lost consciousness almost immediately without any warning.

The gas was heavier than air, so it had flowed through the ventilation system and pulled in the cafeteria where students were eating lunch. The professor showed a diagram of how the concentration would have increased as more gas pumped through the vents, creating a deadly cloud that sank to breathing level.

She explained that the people who collapsed first probably saved others by triggering the evacuation because five more minutes of exposure could have killed dozens of students. The interviewer asked if this was similar to any industrial accidents, and the professor mentioned several oil refinery disasters where hydrogen sulfide leaks had killed trained workers wearing protective equipment.

She said, “The fact that teenagers had created this gas mixture in a school storage room with no safety equipment was absolutely horrifying from a scientific standpoint. Monday marked my return to school, though only juniors and seniors were allowed back while they finished decontaminating the freshman and sophomore wing.

Walking through the front doors felt surreal, like entering a completely different building than the one I’d evacuated a week earlier. Security had been increased with metal detectors at every entrance and guards checking bags for any liquids or chemicals. Students moved quietly through hallways that used to be loud and chaotic. Nobody wanting to be the first to laugh or joke like nothing had happened. My first period was English with Mrs.

Sheffield, and she started class by having us write about our feelings regarding recent events. Most students stared at blank pages, myself included, because what were we supposed to say? Sorry your classmate is in a coma. Hope the kid with permanent lung damage feels better. The whole assignment felt performative and useless, but I wrote something generic about community healing and turned it in without reading it over.

During lunch, the cafeteria was half empty because students were too scared to eat there. I sat outside with a group of people I barely knew. Everyone avoiding eye contact and picking at food. Between classes, I saw Devon for the first time since his arrest.

He was walking with his head down, hands shoved in pockets, completely different from his usual confident stride. When he spotted me, his face did something complicated, like he wanted to talk, but also wanted to disappear. I caught up with him by the lockers and asked how he was doing, knowing it was a stupid question. He said his parents had hired a lawyer who was trying to work out a plea deal, that prosecutors wanted him to testify against Jay in exchange for reduced charges.

He’d been charged as a juvenile with reckless endangerment and providing materials for a dangerous device, which could mean probation and community service instead of jail time. But his lawyer said if he didn’t cooperate fully, prosecutors might try to charge him as an adult alongside Jay. His voice cracked when he talked about how his dad wouldn’t speak to him, how his mom cried every time she looked at him. He asked if I was going to testify, too, and I told him about the grand jury subpoena.

We stood there in the hallway while students float around us. Two kids who’d wanted to be part of something funny and ended up part of something terrible. That week, I had to go to the courthouse for my grand jury testimony. Rachel Gordon coached me beforehand, explaining that grand juries were different from regular trials and that I wouldn’t have a lawyer in the room with me.

She said to answer questions directly without volunteering extra information and to tell the absolute truth because lying to a grand jury was a federal crime. The jury room was smaller than I expected, just a regular conference room with 23 people sitting in chairs arranged in a U-shape.

An assistant district attorney named Laura Chen asked me questions about my friendship with Jay, our group chat conversations, and what I knew about the prank plan. I answered each question carefully, trying not to incriminate myself while also not protecting Jay. It felt like betraying a friend, sitting there explaining how he’d shown us the video and talked about becoming a legend.

But then I thought about Nathan Cross in his hospital bed, about the 12 students with damaged lungs, about families destroyed by one stupid decision. The grand jury members asked their own questions, too. Things like whether Jay had seemed to understand the danger, or if he’d expressed any regret. I said he’d followed a video with hundreds of thousands of views and thought it was safe, that he’d been shocked when people started collapsing.

One juror asked if I felt guilty for not reporting the plan, and I said yes without elaborating, because what else could I say? The grand jury returned indictments against Jay on multiple charges, aggravated assault, reckless endangerment creating catastrophic risk, possession of weapons of mass destruction, and terroristic threats.

The news explained that weapons of mass destruction didn’t just mean bombs or nuclear devices, but any chemical or biological agent capable of causing death or serious injury to multiple people. Jay was being charged as an adult because of the severity of the incident and the number of victims. His bail was set at $500,000, which his family couldn’t afford, so he stayed in juvenile detention, awaiting trial.

Photos leaked of him in an orange jumpsuit, looking skinny and terrified. Nothing like the confident kid who’d shown us that YouTube video. Devon took a plea deal the following week. He plead guilty to one count of reckless endangerment in juvenile court and was sentenced to 2 years probation, 500 hours of community service, and mandatory counseling.

He also had to write apology letters to every student who’d been hospitalized and their families. The judge said Devon had made a terrible decision, but had shown genuine remorse and cooperated fully with investigators, which was why he was receiving a juvenile sentence. 2 months after the incident, Nathan Cross finally woke up from his coma.

The news covered it like a miracle story, showing his parents crying tears of joy as they talked about their son opening his eyes. But the full story was more complicated. Nathan had significant brain damage from oxygen deprivation and would need years of rehabilitation. He couldn’t walk without assistance, had trouble speaking, and didn’t remember anything from the 6 months before the incident.

His wrestling career was over, his college scholarship withdrawn. His future completely changed from one lunch period where he’d been sitting in the wrong place. His parents announced they were filing a civil lawsuit against Jay’s family, Devon’s family, the school district, and the YouTube platform for hosting dangerous content.

They were seeking damages for medical costs, future care needs, and loss of potential earnings. Other families joined the lawsuit until 23 students were represented, all seeking compensation for injuries ranging from lung damage to PTSD. The news about the lawsuit made me realize how farreaching the consequences were, how many lives had been permanently altered by those chemicals mixing in a 2 L bottle. My own consequences came in the form of social isolation rather than legal charges.

Students who’d been hospitalized or had friends hospitalized wouldn’t talk to me, seeing me as guilty by association. My Instagram comments filled with messages calling me a coward for not stopping Jay, saying I was just as responsible as the people who’d mixed the chemicals. Teachers looked at me differently, like they were disappointed I’d been involved, even tangentially.

My parents had to take me out of Jefferson High and enroll me in online classes for the rest of the year because the harassment got so bad. I’d wanted to be cool, to be part of something exciting, and instead I’d lost my school and most of my friends. The isolation gave me a lot of time to think about everything that had happened.

About how a YouTube video with 340,000 views could seem legitimate just because it was popular. I thought about how easy it had been to ignore warning signs and dismiss concerns because we wanted the prank to work. Most of all, I thought about Nathan Cross and whether he’d ever be the same person he was before Jay’s chemicals stole his future. Jay’s trial began in September, right when we would have been starting senior year.

The prosecution presented evidence, including the YouTube video, our group chat messages, receipts for chemicals, and testimony from students who’d been hospitalized. Medical experts explained in graphic detail, what hydrogen sulfide does to the human body, how it binds to iron in blood cells, and prevents oxygen from reaching tissues.

They showed scans of damaged lungs and brain tissue, photos of students in ICU beds hooked up to ventilators. Jay’s defense attorney argued that his client was a child who’d made a terrible mistake, that he’d followed instructions from an online video without understanding the chemistry involved.

The attorney said Jay had thought he was creating a bad smell, not a deadly gas, and that charging him with weapons of mass destruction was excessive. But the prosecution countered with evidence that Jay had researched hydrogen sulfide after mixing the chemicals, that he’d found and read articles about its toxicity, but planted the bottle anyway.

They presented search history showing Jay had looked up hydrogen sulfide symptoms and is H2s deadly the day before he put the bottle in the vent. I was called to testify at the actual trial which was completely different from the grand jury. This time there was a real courtroom with a judge, jury, and audience filled with victims families.

Jay sat at the defense table in a suit that was too big for him, looking younger than 17 as he stared at the table. I had to walk past him to get to the witness stand and he looked up at me with these hollow eyes that made my stomach turn. The prosecutor asked me to describe our friendship and the conversations we’d had about pranks. I explained how Jay had shown us the video and seemed excited about pulling off something epic.

She asked if Jay had expressed any concern about safety or asked questions about the chemicals. I said no, that he’d seemed confident the video was reliable because of its view count and comments. The defense attorney cross-examined me, trying to establish that Jay wasn’t malicious or intentionally trying to hurt anyone.

He asked if Jay had ever expressed hatred towards students or talked about wanting to cause harm. I said absolutely not. That Jay was generally well-liked and had friends across different social groups. The attorney asked if I’d thought the prank was dangerous, and I had to admit I’d been concerned, but hadn’t understood the full extent of the risk.

The trial lasted 3 weeks with testimony from dozens of students, teachers, first responders, and medical experts. The most devastating testimony came from Nathan Cross’s parents, who described their son’s personality before the incident and the limited person he’d become. after his mother broke down on the stand talking about how Nathan didn’t recognize his girlfriend anymore, how he had to relearn basic tasks like feeding himself. She said every day they grieved for the son they’d lost even though he was still technically alive.

His father talked about the financial burden of roundthe-clock care, the medical bills that insurance wouldn’t cover, the future they’d planned that would never happen. He looked directly at Jay and said he hoped the jury would send a message that this kind of recklessness couldn’t be tolerated. Other families testified about children with permanent lung scarring who couldn’t run anymore.

students with PTSD who had panic attacks in enclosed spaces, kids whose promising futures had been derailed by medical problems and trauma. By the end of the victim impact statements, several jurors were crying, and Jay’s head was down on the table. The jury deliberated for 2 days before returning guilty verdicts on all major charges.

Jay was convicted of 23 counts of aggravated assault, one for each hospitalized student, plus reckless endangerment and possession of weapons of mass destruction. The courtroom erupted in mixed reactions with victims families crying and hugging while Jay’s mother screamed that they were destroying her baby’s life.

The judge set sentencing for 6 weeks later, giving both sides time to prepare their arguments about appropriate punishment. Legal experts on the news said Jay was facing anywhere from 10 to 30 years in adult prison. Though some thought the judge might show leniency because of his age.

Victim advocacy groups argued for maximum sentences, saying this needed to be a deterrent for other teenagers who might think dangerous pranks were funny. The case became a national conversation about youth criminal justice with people debating whether a 17-year-old should serve decades in prison for a prank gone wrong or whether rehabilitation should be the priority. During the 6 weeks before sentencing, I tried to process everything that had happened.

I’d lost my best friends, my school, and my reputation. But those losses felt trivial compared to what the victims had experienced. I started volunteering at a children’s hospital, reading to kids with long-term medical conditions, trying to understand what Nathan and the others were going through.

I wrote letters to the families apologizing for not stopping Jay, knowing the words were inadequate, but needing to try anyway. Most letters went unanswered, though Nathan’s mother sent back a short note saying she appreciated my honesty, but couldn’t forgive me yet. I started seeing a therapist to work through the guilt and anxiety that had become constant companions.

She helped me understand that I’d made a mistake by staying silent, but that mistake didn’t define my entire life. She said the important thing was learning from it and making different choices going forward. But some nights I still couldn’t sleep, thinking about how easily I could have prevented everything just by telling a teacher or calling the police. The sentencing hearing was packed with media and spectators.

Everyone wanting to see what punishment Jay would receive. The prosecution asked for 25 years, arguing that Jay’s actions constituted a chemical attack on a school and deserved severe consequences. They emphasized that Nathan Cross would never fully recover, that 12 students had permanent health problems, that dozens of families had been traumatized.

Jay’s attorney argued for 10 years, claiming his client was young and remorseful, that he’d made a catastrophically bad decision, but wasn’t a hardened criminal. He brought up Jay’s good grades, lack of prior arrests, and supportive family as evidence that rehabilitation was possible.

Jay himself spoke for the first time, reading a prepared statement with a shaking voice. He apologized to every victim by name, said he thought about Nathan every day, that he’d give anything to undo what he’d done. He cried through most of it and by the end several people in the courtroom were crying too, including me. But when I looked at Nathan’s parents, their faces were stoned, unmoved by Jay’s tears.

The judge took an hour to deliver her sentence, walking through each charge and the factors she’d considered. She said Jay had shown remorse, but that his actions had caused catastrophic harm to innocent people. She said teenagers needed to understand that pranks involving chemicals or weapons would be treated as serious crimes regardless of intent.

She sentenced Jay to 18 years in adult prison with possibility of parole after 12 years. The courtroom exploded with noise. Jay’s mother screaming while victim’s families alternately cheered or cried. Jay collapsed in his chair, his lawyer grabbing his shoulder to keep him upright. Guards came to take him away immediately, and he looked back at his parents one last time before being led through a side door.

I sat in the gallery feeling numb, trying to comprehend that my former friend would be in prison until he was at least 30 years old. 18 years for following a YouTube video for wanting to be remembered for mixing chemicals without understanding what they’d create.

The news crews rushed out to broadcast the sentence and within minutes it was trending nationwide with people debating whether 18 years was appropriate or excessive. In the months after sentencing, I tried to rebuild some kind of normal life. I finished my senior year online and applied to colleges far from home, wanting a fresh start where nobody knew about Jefferson High or the chemical incident.

I got accepted to a state school 400 miles away and threw myself into studying environmental science, figuring I should probably understand chemistry better than I had in high school. I joined campus organizations focused on chemical safety and youth justice reform, trying to turn my experience into something constructive. Sometimes students would find out about my connection to the case and ask questions, wanting to hear the story firsthand.

I’d tell them about Jay’s YouTube video and the prank that became a disaster, watching their faces change as they realized how easily it could happen to anyone. Some people judged me harshly for not stopping it, and I accepted their judgment because they weren’t wrong. But others understood the complexity of being 17 and not recognizing danger until it’s too late.

3 years after the incident, I went to visit Jay in prison. It took months to get approved for visitation, and I almost backed out a dozen times before finally driving to the facility. Seeing Jay in prison khakis behind plexiglass was surreal, like looking at a different person wearing my friend’s face.

He’d gotten taller and more muscular from prison workouts, but his eyes had this flat quality I didn’t recognize. We talked awkwardly through phones, catching up on superficial things before getting to the real conversation. He asked if I ever thought about that day, and I said constantly that it colored everything I did and every decision I made.

He said being in prison meant thinking about it every single day, living with the knowledge that his stupid idea had destroyed multiple lives, including his own. He’d gotten his GED and was taking college courses through a prison program, trying to build some kind of future for when he got out. But he said he couldn’t imagine what life would look like at 35, whether anyone would hire him or talk to him after what he’d done.

I didn’t have answers, just sat there looking at my friend who’d wanted to be a legend, and instead became a cautionary tale. Nathan Cross died 4 years after the incident from complications related to his brain injury. His obituary mentioned his love of wrestling and his acceptance to college, describing the bright future that had been stolen by a chemical exposure at his high school.

It didn’t mention Jay by name, but everyone knew. The funeral was covered by local news showing hundreds of people gathering to mourn a young life cut short. His parents gave interviews talking about their son’s four-year struggle, how he’d fought hard, but his body ultimately couldn’t recover from the damage.

They said they hoped Nathan’s story would prevent other teenagers from attempting dangerous pranks, that no view count or social media fame was worth a human life. After Nathan’s death, there was a push to increase Jay’s sentence since the assault had now resulted in a fatality. But legal experts said that wasn’t how the justice system worked.

that Jay had been sentenced based on the facts available at the time. The prosecutors did charge him with manslaughter related to Nathan’s death, adding another 15 years to his sentence. Jay plead guilty rather than going to trial again, saying he couldn’t put Nathan’s family through more testimony. Now 7 years later, I’m 25 years old with a degree in environmental science and a job at a chemical safety consulting firm.

I help companies develop protocols to prevent accidents and train workers on proper handling of hazardous materials. Sometimes I wonder if I chose this career as penance as a way to ensure nobody else gets hurt by chemicals they don’t understand. I think about Jay almost every day. Imagine him in his prison cell counting down the years until parole. I think about Nathan and the life he should have had. About his parents who visit an empty bedroom.

I think about the 12 students with scarred lungs who can’t breathe quite right anymore. And I think about the moment I watched that YouTube video and thought it looked fun instead of dangerous. The moment I could have changed everything but chose to stay silent. People ask me sometimes what I learned from the whole experience, expecting some profound wisdom.

But the truth is simple. Popularity isn’t the same as safety. Views don’t equal validity. And staying quiet when you know something’s wrong makes you complicit in whatever happens next. Those lessons cost Nathan his life and Jay his freedom. I just hope sharing this story might save someone else from learning them the same way.

News

CH1 Japan’s Convoy Annihilated in 15 Minutes by B-25 Gunships That Turned the Sea Into Fire

At dawn on March 3rd, 1943, the Bismar Sea lay quiet under a pale sky stre with clouds. The air…

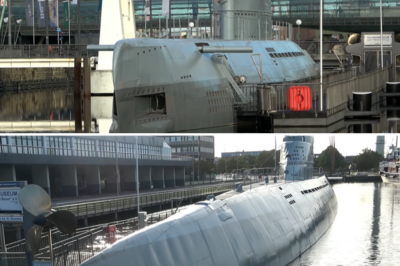

CH1 German WWII Type XXI Submarine Walkthrough & Tour – The Wilhelm Bauer/U2540

in the Final Phase of World War II the German Navy commissioned a revolutionary new type of Submarine design a…

CH1 The Grueling Life of a WWII German U-Boat Crew Member

british prime minister winston churchill famously remarked after the war that the u-boat was the only thing that truly scared…

CH1 U-530: The U-Boat That Escaped to Argentina

At dawn on July 10th, 1945, Argentine fishermen off the naval base at Mardel Plata saw an unexpected silhouette emerge…

CH1 This Was the CHILLING LIFE of Germans Inside a SUBMARINE!

German submarines known as Yubot were a key part of national socialist naval strategy. They were small cramped vessels where…

CH1 What Happened When the 1st SS Met Patton’s Elite at the Bulge?

By the end of 1944, after a series of military defeats on both fronts, the Third Reich found itself on…

End of content

No more pages to load