I didn’t start this war. I built a fence. That’s it. But when the HOA sent their fake security boys to cut my wire and then tried to steal my land, I answered with 8,000 volts of legal Texas electricity. They thought they could drag me to court. By the end, they were the ones begging for mercy. I’ve lived long enough to know one simple truth. Peace never lasts forever.

Not out here. Not on land that remembers more than you do. My name’s Clay Banner and this stretch of sunburned Texas dirt, every rock, every cedar stump, every post hole has carried the weight of my family since 1931. My granddad carved the first fence line with a borrowed mule and hands that shook from the Great Depression.

My father kept the place alive through droughts, cattle sickness, and a tornado that took half the barn roof, but somehow left the old windmill spinning like nothing happened. And now it’s my turn. 120 acres, just wide enough to breathe in, just quiet enough to hear yourself think. Most mornings start the same. I step out onto the porch before the sun clears the ridge.

The air still smells cold at that hour. Cedar, dust, and whatever the coyotes left behind on their night patrol. My boots find the same worn grooves along the porch boards, and my old dog, Duke, trots beside me, yawning like we’re already behind schedule. By 6, I’m checking the cattle, tapping each water trough to hear if the levels dropped overnight.

Then it’s fence inspection, line by line, the same way my father taught me. Not because I expect trouble, just because trouble finds you faster if you stop looking. For most of my life, that routine was enough to keep the world at the right distance.

The town knew me, the sheriff knew me, and the neighbors, well, the real neighbors, respected a man who worked his land and minded his business. But the world changed. Or maybe it just shifted a little north, right up against my gate. When the Clear Hillacres development went up beyond my northern boundary, it rose overnight like a rash.

Streets carved too straight, lawns trimmed too close, and houses stacked in perfect rows that never matched the curve of the land. They carved a road where cattle used to wander. They planted trees that had no business surviving Texas heat. and they filled those new homes with people who liked the idea of the countryside without respecting the reality of it. At first, I didn’t care.

Let them water their lawns and post their neighborhood rules about mailbox colors and acceptable bird feeders. None of that had anything to do with me. My deed was older than their entire subdivision. My land was registered long before HOAs were a glimmer in some developer’s eye. Still, something inside me tightened when I saw that road built so close to my fence line. It wasn’t fear.

It wasn’t anger, either. It was that old rancher’s instinct. The feeling you get when a storm’s coming, but the sky still looks clear. So, I decided to upgrade the northern fence. Not to provoke, not to posture, just to draw a clean, strong line between a world of clipped hedges and a world that answers to sun, soil, and sweat. I sank every post myself. Treated cedar with steel core straight as rifle barrels.

Ran the wire tight enough to hum when the wind shifted. Mounted solar cameras every 50 ft. Hung signs every 10. Private property. No trespassing. Video surveillance. If a man can’t understand that message, then the problem isn’t the sign. By the time I finished, I stood back and wiped dust off my hands.

The sun was dropping low, turning the whole fence into a copper line stretching toward the horizon. I felt something settle in my chest then, a kind of quiet pride. But peace is fragile, and some folks can’t stand seeing a line they didn’t draw. It started small. A glance from a passing jogger, an SUV slowing down to stare longer than normal, a group of teenagers pointing at my cameras like they were props in a theme park. I ignored it.

I kept to my land. I kept to my cattle. I kept to what was mine. Then one morning, I opened my mailbox and found an envelope so polished it looked like it was afraid of dirt. Creamcoled embossed seal addressed not to Clay, but to property owner, Northern Boundary Zone. No return address, just a name printed at the bottom. Bradley Sloan, president, Clear Hillacres Homeowners Association.

I didn’t know him. Didn’t want to. Didn’t need to. I stood there on my porch, holding that envelope, the wind tugging at the corner like it had something to say. And for the first time, I felt that storm I’d sensed weeks earlier begin to gather. Far off, quiet, but real. I opened the envelope, read the first line, and laughed out loud. A long, slow, disbelieving laugh.

Because whatever war they thought they were starting, they had no idea who they were messing with. I remember standing there on the porch. The letter opened in my hands, Duke sitting at my boots like he was waiting for a verdict. The morning sun hadn’t even burned off the haze yet, but my day was already heading downhill.

The letter was written in a tone that tried real hard to sound official. That kind of polished language folks use when they want to boss you around without sounding like they’re bossing you around. It said my newly installed fence was non-compliant with the established aesthetic standards of the Clear Hill Acres community.

It went on to say, “I was required to remove unauthorized visual obstructions within 3030 days to preserve neighborhood harmony.” Neighborhood harmony. That one got a snort out of me. There are a lot of ways to describe my land. Rugged, dusty, sunbaked, stubborn, but harmonious ain’t one of them, and it sure as hell wasn’t part of their neighborhood.

I finished my coffee, folded the letter in half, set it on the kitchen table, and went on with my day like it was a piece of junk mail. because that’s what it was, a mistake. Someone checked the wrong box on their clipboard and sent the wrong letter to the wrong man. But 2 weeks later, the second envelope showed up. This one wasn’t polite. It wasn’t even pretending.

Bigger envelope, heavier paper, same glossy HOA seal stamped on the front like they were trying to make it look like a government document. I brought it inside, sat down at the table, and slid a pocketk knife under the flap. Duke wandered over and laid his head on my knee like he could smell trouble coming before I even finished reading.

Inside was a formal notice of continued violation. A whole packet of printed pages, paragraphs written like someone had swallowed a legal dictionary. It said my failure to respond constituted non-compliance. It said I was creating a public safety concern. It said the HOA was prepared to escalate matters.

and tucked in the back, a small blurry satellite map with a thick red outline drawn around the northern edge of my property as if it belonged to them. That part didn’t make me laugh. I stared at that red line, then out of the window toward the ridge, and a slow warmth crept up the back of my neck. Not anger, not yet. Just that rancher’s sense again. The one that tells you something ain’t right. So, I wrote back.

Not on some fancy stationery, not on printer paper, on a page torn out of a lined notebook. The kind kids use in middle school. I wrote in all caps, partly to annoy them, partly because it felt right. I told them my land wasn’t part of Clear Hill acres. Never had been, never would be.

I attached a photocopy of my deed, my parcel registration, and the historic boundary map that’s been on file longer than every person in that HOA’s life team combined. Then I signed the bottom. Clay banner owner independent as hell. God bless Texas. I folded it, slid it into a plain white envelope, and mailed it off. And for a week or two, things got quiet again.

The kind of quiet that makes you think maybe, just maybe, common sense has prevailed. But trouble, real trouble, doesn’t knock on your front door. It doesn’t call ahead. It doesn’t leave a voicemail. Sometimes it climbs your fence in broad daylight. Sometimes it carries bolt cutters. And sometimes it shows up wearing a polo shirt with a fake security badge stitched on the chest, but I didn’t know that part yet because back then, sitting at my kitchen table with the second letter folded beside my plate, I thought the storm was fading.

Turns out it was just gathering strength. It was a Thursday afternoon when the first motion alert buzzed on my phone. I remember because I was kneede in mud working on a stubborn water valve that had been leaking since spring. Duke barked once, just one sharp low sound, and looked north.

I pulled off my gloves, swiped the phone, and the camera feed popped up. Two men standing right at my fence line, HOA polos, tucked into khaki pants like they were going to a job interview at a lawn care company. One was tall and skinny, the kind of man who looked like he’d blow over in a Texas windstorm. The other one, heavier set, red in the face, built like a man who had spent more time yelling than working. Both of them were holding clipboards.

That alone told me everything I needed to know. There’s a certain type of man who uses a clipboard like a badge. Like holding one gives him power he didn’t earn. The skinny one was snapping pictures through the slats. Click, click, click, like my fence was a crime scene. The bigger one traced his hand along the top rail like he owned it.

Then I watched the moment everything shifted. The larger man placed one boot on the lower beam, grabbed the top of the fence, and started to climb. Didn’t read the sign right in front of his face. Didn’t care he was stepping onto private ranch land. Didn’t even think to knock. Just climbed. Slow, deliberate, like a raccoon with a badge.

I didn’t shout, didn’t run out there, didn’t say a word. I just watched. Because one thing my grandfather taught me and taught me hard was this. Never confront a fool before you collect your evidence. So I saved the video, tagged the file, moved it to a locked folder with a name no one but me would ever guess.

About 10 minutes later, the two men climbed back down, scribbled something on their clipboards, and walked off toward the development road without a care in the world. You’d think that would have been the end of it. But a few days later, I found the first real sign that this wasn’t just an overzealous HOA doing a driveby inspection.

I was checking the fence line after a windstorm, just walking slow, making sure nothing was downed, when I noticed it. The top wire cut clean, not frayed, not broken by weather, cut. The clip was smooth, high, and done with a bolt cutter. You couldn’t miss it. Somebody had leaned in under the no trespassing sign and snipped it like they were pruning a weed. I stood there a long moment, thumb hooked in my belt, staring at the orange tagged post where I keep my boundary markers.

My land doesn’t give up signs easy, but when it does, you pay attention. I pulled up the camera feed again, scrolled back through the timeline, and there he was. Same man, same hoa polo, moving along the fence line like a possum with a purpose, glancing around, crouching, cutting. That did it. Laughing at a letter is one thing. Watching a grown man trespass onto your land with bolt cutters, that’s something entirely different.

So that evening, after feeding the steers, I called in my first police report. Officer Judson rolled down my driveway about 20 minutes later. His cruiser made that familiar crackling sound on gravel, the one I’ve heard since I was a boy. Judson’s a good man. Helped me round up loose cattle once, never asked for anything in return.

He stepped out, stretched his back, leaned on the hood. All right, Clay, he said. Let’s see what we’ve got. I handed him the printouts. He whistled low, long, and slow. This is criminal trespass, he said. And that right there, he pointed at the bolt cutter frame, is property damage. I nodded. I figured you’d say that. Judson adjusted his hat, looked north toward the new houses popping up on the ridge.

These HOA folks, he muttered. They forget where the pavement ends. He wasn’t wrong. And as I stood there under the last light of the evening, looking out across land my family had held since 1931, I felt something quiet settle in my chest. Not rage, not fear, resolve.

Because now I knew something I hadn’t known before. This wasn’t a misunderstanding. This was a test. And they were about to learn they’d picked the wrong fence to mess with. The kind where the air hangs still, the cicas go silent, and the moon looks like someone shaved a sliver off the edge. I had just finished locking up the barn when the first motion alert buzzed on my phone.

12:47 a.m. Duke’s ears perked before I even pulled the screen up. Camera 6, north fence, infrared mode. A lone figure moved along the boundary, slow, crouched, careful, hood up, backpack slung tight, every step deliberate like he’d walked this fence before. And in his hand, even through grainy night vision, I knew that shape. Bolt cutters.

I froze the feed. zoomed in, my jaw clenched. Same build, same shoes, same walk, same HOA patrol guy from the daylight trespass. Except tonight he thought he was clever. Hoodie instead of polo, scarf instead of badge. But fools don’t get smarter at midnight. They just get bolder.

I unpaused, watched him reach up, line up the cutters, and squeeze. Snap. Clean cut. But the thing he didn’t know, the thing I had been waiting for, was that I’d replaced that very section two days earlier with a dummy wire hooked to a tiny die pack. Not harmful, not dangerous, just messy. And right as he leaned through the gap, pop a sharp little burst of pressure. The camera caught the cloud perfectly.

A bright, ridiculous explosion of neon orange dye splattering across his sweatshirt, face, and backpack like a paint factory sneezed on him. He stumbled backward, waving his arms, slipping in the dirt, cussing loud enough for the microphone to pick up half the words and imply the other half.

Then he ran fast like a man who suddenly realized he was about to have a real bad morning. I saved the clip, filed it, printed frames. I even kept the audio where he screamed, “A hell, he tricked us.” That one I plan to use. I was still sorting the files when headlights swept across my porch. A familiar truck engine rumbled to a stop. Not Judson.

Sheriff Hayes, a big man with gentle eyes and boots older than half the county. He stepped out slow, hat under his arm. Clay, he said, voice low. We got a report of a suspicious figure running through Clear Hill acres. Orange as a jacko’lantern. Figured I’d check on you first. I just handed him the tablet. He watched the clip without saying a word. Didn’t blink. Didn’t hurry.

When the die pack popped and the guy fell backward, Hayes let out a long exhale through his nose the way a man does when something is equal parts stupid and predictable. Well, he finally said that there is criminal trespass. No question about it. Maybe attempted vandalism, too. I nodded. Thought you’d say that. He walked to the fence, shined his flashlight on the warning signs I’d posted every 10 ft. Electric? He asked.

Not yet, I said. legal when I do though. Agricultural use certified section 117. Hayes smiled. Not a friendly smile, a knowing one. I’ll note that in my report, he said, “Make it clear you’re within your rights. These HOA fellas, they forget Countryland don’t work the way their little rule books say it does.

” He tipped his hat, looking north toward the development. Clay, this won’t be the last time they try something. They didn’t get what they wanted tonight. I folded my arms. And what do you think they wanted? Hayes gave me a long, steady look. Not your fence, he said. Your land. He climbed back in his truck, rolled down the window before pulling off.

You call me if they come back. And Clay, be ready. When his tail lights disappeared down the road, the night felt different, like the line had been crossed. Not by me, but by them. And from that moment on, this wasn’t a dispute. It was a fight. The morning after the dieac incident, the sky was still gray when Duke started barking. Not his usual stranger on the road bark. Not coyotes either.

This was the sharp, short warning bark he only used when something felt off. I stepped onto the porch with my coffee. And that’s when I saw it. A black SUV rolling slow down my driveway. Not the sheriff, not a neighbor, too clean, too polished, too out of place on gravel. The SUV stopped and outstepped a man who looked like he ironed his posture every morning.

Pressed slacks, leather shoes, hair combed with mathematical precision. He carried a leather folio, the kind city men use when they want to pretend they’re important. He looked around my ranch like he was measuring it for a sale. Then he forced a smile. Mr. Banner, he said, extending a hand I didn’t take. Bradley Sloan, president of Clear Hillacres Homeowners Association. So, the man finally had a face. He wasn’t tall.

He wasn’t strong, but he radiated that certain type of confidence, the kind built on paperwork and signatures, not soil and sweat. “What can I do for you?” I asked. He took off his sunglasses and that smile got thinner. “Well, let’s just say last night caused a bit of concern.” I raised an eyebrow. “You mean the trespass?” He waved a hand like swatting a fly.

a misunderstanding that told me everything I needed to know. He didn’t come here to talk about the crime. He came because someone came home stained orange and crying. Anyway, he continued, I’m here to propose something mutually beneficial. Mutually beneficial. That phrase should come printed on a red flag. I kept a straight face, but inside I was already reaching for the small digital recorder in my shirt pocket. Old habit from my military days.

old friend taught me. Never walk into negotiations without proof of what was said. I clicked the recorder on with my thumb. Go on, I said. Bradley cleared his throat, clasped his hands together like he practiced this in front of a mirror. Look, Clay, may I call you Clay? No. Right, Mr. Banner. The folks in Clear Hill Acres, well, they weren’t expecting a tall wooden fence right next to their property line.

Not their property line, I corrected. It’s mine. He chuckled politely, ignoring that. So, here’s what I’m thinking. What if, just hear me out, we take this burden off your hands, the Northern Strip, maybe 30, 40 ft of it. We could purchase it at a very fair price. Gives you less to maintain.

Gives us room to improve the neighborhood buffer. I took a slow sip of coffee. How much? I asked, keeping my tone flat. He brightened like a salesman who thinks he’s about to close a deal. We could offer 50,000 straight cash buyout. Quick, clean, tax beneficial. I nodded slowly. And what happens if I say no? His eyes narrowed just a hair, just enough to betray the mask.

Well, then the association might have to continue filing safety claims, fence violations, environmental concerns. You know how these things can drag out. There it was, the quiet part spoken just loud enough for a recorder to hear. I looked him dead in the eye. You threatening me, Bradley? He forced a laugh. Oh, no, no, nothing like that. Just offering solutions.

You see, when things get difficult, sometimes it’s better to resolve matters privately. No need for lawyers. No need for escalation. I let the silence stretch, long, heavy. Then I stepped closer, just one bootlength. You came onto my land, tried to buy what isn’t for sale, and tried to scare me into it with fake safety complaints.

he swallowed. I wouldn’t put it that way. I would. He cleared his throat again, suddenly losing that perfect posture. Well, the offer stands. But I do hope you will consider working with us. It’d be a shame if a simple fence caused ongoing complications. I smiled at him, a slow, deliberate smile I learned from my grandfather, the kind that isn’t friendly at all.

Bradley, I said quietly, you should head on back to your development. He blinked. Is that a no? It’s a get off my land. His jaw tightened. He put his sunglasses back on, walked stiffly to his SUV, and drove off without another word. I stood there until the dust settled.

Then I pulled the recorder from my pocket, stopped the recording, and slipped it into my jacket. That audio was going to matter, a lot more than he realized. And for the first time, I knew this wasn’t about fences, wasn’t about aesthetics, wasn’t even about the HOA. This was about land, my land. And Bradley Sloan had just declared himself my enemy. I didn’t sleep much that night, not because of fear.

Fear left my body the same year I shipped out with the army. But because of anger, the slow, quiet kind that settles behind your ribs and waits. By sunrise, I knew exactly what I needed to do. See, when somebody tries to rewrite your boundaries, literally redraws your land on a map like a third grader with a red crayon, you don’t argue with them.

You go to the people who keep the real maps. So, I fed the steers, grabbed my paperwork folder, whistled Duke into the truck bed, and headed into town. The county building sits on the corner of a dusty lot behind the post office. Same spot it’s been since the 1950s.

brick faded by sun, gutters sagging, flag flapping slow in the morning wind. Inside, behind the front counter, sat Roberta. Same Roberta who had been working there since I was a boy. Same woman whose granddad shued my granddad’s horses. The kind of Texan who knows the county better than any GPS ever will. She looked up from her desk, smiled without standing.

Well, now if it ain’t Clay Banner, trouble following you or are you following it? I set the stack of HOA letters on the counter. Bit of both, I said. She adjusted her glasses, flipped through the envelopes, then nodded like she’d already guessed the ending. I’ve been hearing about those Clear Hill folks. They’re enthusiastic.

That’s one word, I muttered. All right, she said, pushing her chair back and wheeling to the old computer. Let’s pull your parcel up. Click, click. A long beep from the ancient scanner. Then the big county map popped up. green, tan, white patches, all outlined in thin black lines like a quilt. Roberta tapped one corner with her pencil. Here’s your land just like it’s been since 1931.

And the HOA. She zoomed out, scrolled north, then pointed to a faded dotted outline. Here, Clear Hill Acres stops right at this line. That looks a long way south of my fence. 43 ft. She confirmed. 43 ft of land they’ll never touch unless you gift wrap it. I felt something loosen in my chest.

Not relief, just confirmation of what I already knew. Roberta turned to me, eyebrows raised. “You want a print out?” “Two copies,” I said. “One for me, one for someone who needs to read it slow.” “Oh, honey,” she chuckled. “I’ll laminate it.” 5 minutes later, she handed me two Yar laminated parcel maps. Clear as day, stamped, certified, undeniable.

Clay, she said more quietly as I folded them. These HOA types don’t understand land. They understand paperwork. And this, Sur, she tapped the map. Is the paperwork that ends arguments. I thanked her, loaded Duke back into the truck, and drove straight home. Before lunch, I mailed one laminated copy to Bradley Sloan’s office. No fancy letter, no message, just a bright orange sticky note slapped on the front.

Stop trespassing. You’re out of your jurisdiction. I walked back to the house, poured myself a cup of coffee, and stood on the porch, watching dust blow across the pasture. That was the moment the shift happened. Up until then, I’d been reacting.

But with that map in my hand, with county certified proof stronger than any HOA covenant, I felt the ground settle under me again. They’d been trying to fight me with fake authority. Now I had the real thing. And when men like Bradley lose the paperwork battle, they don’t calm down. They escalate. I knew the storm wasn’t over. But now I finally had lightning on my side.

With the laminated map sent off and the county now standing squarely behind me, I knew one thing for certain. The paperwork phase was over. The next part wasn’t going to be written with ink. So that afternoon, I hitched the trailer, loaded Duke in the truck bed, and drove into town to buy every grounded statecertified part I needed for a legal Texas agricultural electric fence.

Old Walt at the counter squinted at my cart full of insulators, grounding rods, a solar energizer, and a pile of yellow warning signs as tall as a hay bale. You going electric now, Clay? Seems I’ve got neighbors who don’t understand curly wire and polite signage. He nodded without asking more. Old ranchers know when not to pry. Back on my land, I walked the northern boundary slow. The air was warm.

Wind carrying that faint cedar scent that always reminds me of my grandfather’s shed. Old tools, old wisdom, still useful. I reinforced the posts first, checked the line tension, drove the grounding rods deep into the soil, mounted the solar energizer on the post I’d set months earlier for this very reason. Then came the wire. High tensile steel core stretched until it sang a thin metallic note in the breeze. A sound only ranchers hear.

A sound that says, “This fence means business.” I tested the voltage. Perfect. Enough to send a loud, memorable message. Not enough to hurt anyone who wasn’t trying hard to be stupid. By sundown, I stapled the final warning sign. Electric fence. Agricultural use. Do not touch every 10 ft. reflective paint. No excuses.

When I flipped the Energizer on, the low hum traveled the length of the line like an invisible echo. Duke tilted his head at it, then plopped down in the grass. Approval, ranch dog style. For the first time in weeks, I felt settled. Not done, not safe, but anchored. And right on Q, the storm came knocking. The next morning, while fixing an irrigation elbow, my tablet buzzed with a motion alert. Camera 2, northwest corner.

I wiped my hands, tapped the screen, and there they were. The same two HOA security boys from the trespass weeks earlier, matching sky blue polos, matching sunglasses, even though the sun hadn’t fully come up, matching over confidence. They strutdded up to my fence like deputies from a discount catalog.

The skinny one leaned toward a knot hole, squinting through like he expected to catch me burying gold in the pasture. The heavier one placed a full palm on the top rail. And then, zap! A crisp, beautiful crack split the quiet morning air. The man’s body jolted like he’d accidentally hugged a hornet nest. His hat flew off. His clipboard followed. He made a sound no grown man should ever make in public. Something between a yelp and a high note whistle.

His buddy froze solid, eyes wide, mouth open. Then he dropped his phone in the dirt and scrambled backward like a man who just learned the stove really is hot despite all the labels. I replayed the moment twice, not out of spite, but because it was proof. Proof they’d trespassed. Proof the fence worked.

Proof they weren’t done with me, and I wasn’t done with them. I saved the clip, backed it up to three drives, printed still frames just in case. While the electric hum drifted along the fence line, Duke sat beside me, tail flicking, almost like he was amused. “He ain’t the last one, boy,” I said. Duke huffed like he already knew.

“Because here’s the truth about bullies dressed in HOA polos. They don’t quit when they’re wrong. They double down.” So, I stood there at the edge of my land, arms crossed, the sun creeping up over the cedar ridge, and I felt the next phase rolling toward me like a dust cloud on a summer road. They were going to come complain. They were going to come angry. And they were going to bring company.

But what I didn’t know, not yet, was that tomorrow morning when they showed up, they wouldn’t be alone. A news crew would be right behind them. And that was the day everything went public. The good thing about living out here is you can hear trouble long before it lands on your porch. That next morning, I heard it before Duke even lifted his head.

Gravel popping under stiff tires. A little too fast. A little too angry, I stepped out onto the porch with my coffee mug, still warm in my hand, and sure enough, a gleaming black SUV rolled up my driveway like it owned the place. Bradley pressed khaki pants, polished loafers not meant for dirt. A smile that didn’t reach his eyes.

The man stepped out holding a manila folder like it was a sheriff’s badge. He didn’t even look at the scenery, the open pasture, the quiet wind, the long horizon. Folks like him never do. They’re too busy looking at whatever they want to take. He marched straight toward my porch. “Mr.

Banner,” he called, adjusting his sunglasses. “We need to discuss an urgent violation.” I took a slow sip of coffee. Didn’t rush, didn’t blink. “Morning to you, too, Bradley.” He pretended not to hear. “That’s something HOA people are good at, hearing only themselves.

I received reports, he tapped the folder, that you’ve installed an illegal electrified barrier on a community adjacent boundary. This violates safety codes, public access expectations, and section 4A of Ridge View community guidelines regarding shared aesthetics. I snorted. It’s my land, Bradley, not your community. And that fence is 100% legal. Sheriff Hayes signed off on it himself. Bradley pulled off his sunglasses like that was supposed to intimidate me. Clay, listen to me carefully.

I’m giving you a chance to avoid a substantial fine and potential escalation to civil court. Remove the fence today. I set my coffee cup on the railing, making the faintest tap against the wood. And if I don’t, I asked. Bradley straightened his spine. Then the board will pursue formal action. And trust me, there will be consequences. I smiled.

Not big, just enough to make him uncomfortable. You already sent two of your security boys to cut it, I said. One of them squealled like a hog when the line bit him. You ought to teach him to read signs. Bradley’s face twitched, just a hair. He hadn’t expected me to know. He definitely didn’t expect me to have proof.

He opened his mouth to counter when the sound hit us both. Tires on gravel, fast, not angry this time, hungry. A white van rounded the bend, slid to a stop, and two people hopped out with cameras, microphones, and that wired up excitement only news crews get when they smell a good story. Channel 5 Action News, Bradley’s worst nightmare.

The reporter, a woman in her 40s with confident strides, approached with her mic raised. Mr. Banner, we received a tip that the HOA attempted to remove legally installed agricultural fencing on private property. Are you willing to comment? Bradley spun toward her, panic spreading under his skin like a rash. This is private business, he snapped.

You can’t be here. You’re trespassing on. It’s Clay’s Land. I cut in calmly. He invited no one. Y’all drove onto my property without permission. But they I nodded toward the news crew. They’re on the public turnaround right behind the Cedar Line. Perfectly legal. Bradley’s jaw clenched hard.

The reporter turned to him. Sir, are you with the Ridge View HOA? I serve as president, he said stiffly. Did your officers attempt to breach Mr. Banner’s fence yesterday morning. That is a gross mischaracterization. Because, she interrupted, we were sent a video showing two Ridge View security personnel approaching the boundary, one appearing to touch the wire despite visible warning signs.

We understand the fence complies with Texas Agricultural Code. Bradley blinked, visibly sweating now. Access to community space must remain uniform. There is no community space on my land, I said softly. The reporter looked between us, sensing the tension rising like heat off asphalt. Mr. Bradley, can you explain why your HOA believes it has authority over acreage the county lists as privately deed to Clay Banner? And can you confirm reports that you approached him with an unsolicited offer to purchase a strip of his northern property last week? Bradley stuttered. He He misinterpreted. And right there, that stutter, that crack

was when the camera zoomed in. I didn’t say a word. Didn’t have to. The news crew circled him like curious hawks, peppering him with follow-ups, each sharper than the last. Bradley tried to talk over them, tried to wave the folder in the air. Tried to drown in excuses faster than he could make them.

But once a man starts melting on camera, there ain’t no stopping the puddle. Eventually, he stormed back to his SUV. No victory speech, no threat, no dignity. The director inside the van whispered, “Got it.” every second. Before they left, the reporter turned to me. “Mr. Banner, we may follow up. If this escalates, the community will want transparency.” I tipped my hat.

“Ma’am, I’ve got nothing to hide.” Duke barked once, as if agreeing. The van rolled away, the dust settled, and I knew right then this was no longer Clay versus the HOA. This was public. This was pressure. This was the shot heard around the whole county.

But what I didn’t know, not yet, was that Bradley wouldn’t take humiliation lying down. Tomorrow, he’d come back with something far worse than cameras. He’d come back with the lawyers. I spent the next morning doing something most folks never associate with ranch work. Building a legal war chest. Not guns, not barbed wire, not voltage. Paperwork. The kind of paperwork that sinks ships.

I laid everything out across my dining table, the one my grandfather built from reclaimed barn timber back in ‘ 62. The sunlight coming in from the kitchen window hit each folder just right. HOA letters, the laminated county map Roberta printed, photos of the cut fence, timestamped screenshots from my camera system, and that beautiful orange die splatter photo from the nightcrawler who thought he was invisible.

I started sorting them into piles like ammunition, exhibits, reports, evidence, timeline. Every piece had weight to it. Every piece told a story, a story the HOA wasn’t prepared to hear. But the last folder, that one was the kill shot. Inside were two things. The audio clip of Bradley trying to make it all go away.

The developers access road sketch I’d pried loose from a friendly surveyor who didn’t like being lied to by suits. That sketch showed exactly why Bradley wanted my fence gone. Not aesthetics, not community harmony. They wanted a road through my land to reach a bigger development deal. It was greed, plain and simple. I stared at that folder for a long moment.

The way a man looks at a loaded round before sliding it into the chamber. This wasn’t self-defense anymore. This was counterattack. I picked up the phone and dialed Daniel Torres. He answered on the second ring, voice rough like gravel under a boot. Well, damn, he said.

I’m elbowed deep in my Mustang carburetor and suddenly you call. That usually means somebody’s about to get sued into the stone age. HOA lawyer came by. I said, “Dropped a threat package thicker than a church himnil.” Daniel let out a dry laugh. Let me guess. Kellerman. Slick hair. Smells like he bathes in filtered city water. That’s him. Typical. Bradley loves hiring guys who never sweat. He paused.

All right, Hermono. What’s the real issue? He’s trying to resurrect some future access corridor claim. Says my fence is blocking community expansion. Daniel barked a laugh loud enough to rattle my eardrum. Oh, hell no. They’re still using that antique scam.

Clay, I beat that argument in ’09, 14, and just last year. These HOA types recycle bad ideas like yard sale blenders. You free Monday? I asked. For you? I’ll cancel breakfast and garage time. My wife will curse me in two languages, but she’ll survive. You’re going to need a big briefcase, I said. I’m bringing two. And Clay, listen. His voice shifted lower. Calm, deadly calm.

The tone he used overseas when he warned me a sandstorm or mortar round was coming. You’ve got the truth, the dirt, and the law on your side. They’ve got ego and powerpoint. Bullies don’t scare me, especially HOA bullies. Something settled inside my chest. Not comfort, resolve. See you Monday, I said. You better. And Clay? Yeah, I’m bringing my lucky boots.

the ones I wear when I know somebody’s about to lose. I hung up and looked back at the table, the map, the photos, the folders stacked like defensive walls. Outside, the wind rolled across the pasture, brushing the cedar posts of my fence line. The same fence line that had become a symbol in town.

The line where a rancher finally told an HOA they’d pushed too far. Monday was coming. And with Daniel Torres walking into that courthouse beside me, I knew one thing for certain. They weren’t ready for the fight they picked. Daniel Torres showed up just after sunrise, rolling into my driveway in his dusty Silverado, the same truck he’d driven since we left the service.

I heard the engine before I saw him, that familiar low growl of a V8 that sounded like a tired bull waking up. He stepped out, boots hitting gravel with the weight of a man ready for battle. His hair was a little longer than it used to be, but those eyes still sharp as a fence staple. Morning, Hermono,” he said, holding up a thermos.

Brought coffee strong enough to burn paint off a tractor. “You’ll need it,” I said. “I’ve got the battlefield set inside.” We walked into the house, straight to the dining table, covered edgetoedge with folders, printed maps, camera stills, screenshots, and the laminated county map Roberta had proudly declared indisputable.

Daniel stopped halfway to the table and just whistled. “Well, I’ll be damned,” he said. Clay, this isn’t evidence. This is artillery. He started flipping through the piles, careful, methodical, the way he used to check radio frequencies before patrols overseas. HOA letters, pictures, timestamps, fence damage, trespass footage.

He tapped one folder with his finger. You even printed the orange die shot. Nice. Judges love visual drama. Then he froze. His eyes landed on the folder I’d set aside. the one with the audio and the access road sketch. What’s this? He asked. Open it, I said. He did, and he stopped breathing for half a second. Where the hell did you get this? He whispered. Surveyor friend.

Didn’t like being lied to by HOA board members. Daniel leaned back in his chair, jaw set like he’d just found a loaded ace at the bottom of the deck. This isn’t a fence dispute, he tapped the sketch hard. They want a road, a feeder lane. probably leads to a bigger subdivision or a golf resort contract. Exactly.

And they tried to cut your wire and intimidate you into selling the land quietly. Classic maneuver. He shook his head. But that audio, Clay. That’s the nail in their coffin. He looked at me, eyes full of something between respect and disbelief. You realize what you’ve built here? A fence? I asked. No, he said. A case. A real one. Hell, Clay. Half the attorneys I know don’t prep this thoroughly.

If you weren’t a rancher, you’d make one hell of an investigator. I shrugged. Land teaches you to pay attention. He grinned. And the military taught you to document everything. We spent the next two hours doing something that felt half like legal strategy, half like planning a battlefield assault. Daniel sorted the evidence piles into three stacks. Defense, offense, fatal blows.

That audio fatal blow, he said. This sketch, he held it up like a sheriff holding a stolen wallet. Also, fatal blow. And the video of their guy cutting my wire, that goes into offense. Strong offense. He took out his laptop, an old beatup thing covered in stickers from past cases and a faded Marine Corps decal.

“All right,” he said, cracking his knuckles. “Let’s draft your counter claim,” he started typing, muttering under his breath as he wrote. trespass, willful property destruction, attempted coercion, false legal threat, misuse of HOA authority. Then he paused. You know, he said, “We’re not just asking the court to dismiss their complaint.” No, no, we’re going after damages.

How much? He looked up at me with that grin I remembered from a dozen dust storms and two too many bar fights. I’m thinking six figures. I raised an eyebrow. six figures for a fence fight for what they did, for what they tried to do. He leaned forward. Clay, they cut your fence. They threatened you. They lied. They tried to buy you out under pressure and they misrepresented land boundaries. He tapped the sketch.

This is premeditated expansion fraud. I’ve taken people to court for less and walked out with damn near 200,000. I leaned back in my chair, feeling the old boards creek beneath me. So, what number are we aiming for? Daniel typed one last line, then turned the laptop toward me. 135,000 seem fair, he asked.

I stared at the number. It wasn’t about the money. It was about the principle. It was about the dirt my grandfather left me. The dirt I’d bled on, sweated on, and refused to surrender. “Yeah,” I said. “It’s fair.” Daniel closed the laptop and snapped it shut like sealing a verdict. We’ll file this in the morning, he said. And Clay, yeah, once this hits their inbox, they’re going to panic.

They’ll try something stupid. They always do. I nodded. Let him try. He smiled. Slow and dangerous. That’s why I brought my lucky boots. The Travis County Courthouse had that familiar smell. Lemon floor wax, old paper, and air so dry it felt like it had opinions of its own. I hadn’t been here in years.

Last time I was testifying for a neighbor whose cattle had been rustled. This time I wasn’t a witness. I was the defendant, at least on paper. Daniel and I walked through the double doors like two men stepping onto a battlefield we’d already memorized. We weren’t nervous, just ready. The place was packed.

Clear Hillacres residents filled the first two rows, stiffbacked and whispering like someone had stirred up a hen house. Their safety team officer, the same guy who had hugged my electric fence like it was an old friend, sat up front wearing his vest, chin tucked, looking like he expected applause. On my side, a handful of ranchers, people I didn’t know.

They nodded at me the way country folks do when one of their own gets dragged into a fight he didn’t start. Judge Evelyn Hart entered, small, sharpeyed, and with the kind of presence that could hush cattle. The room went still. Clear Hillacres Homeowners Association versus Mr. Clayton Banner.

She announced the HOA attorney. Kellerman, slick hair, cologne thick enough to stun a mule, stood first. Your honor, we are here because Mr. Banner erected a hazardous electrified barrier that violates community safety standards and endangers. Daniel stood up smooth as a sunrise. Your honor, if I may, we’d like to present our evidence in a logical sequence to avoid confusion.

The judge nodded. Proceed. Daniel reached for the laminated county parcel map, the one Roberta had proudly printed and sealed like it belonged in the Smithsonian. He placed it onto the screen. This is the official county map, he said. It shows Mr. Banner’s property line clearly.

It also shows the HOA boundary line, which stops 43 ft south of his fence. The judge narrowed her eyes. So, the HOA has no legal jurisdiction over his land. Correct, your honor. Kellerman tried to stand, but the judge cut him off with a single raised hand. Do you contest the accuracy of the county’s own records? He swallowed hard. We believe there may be. No discrepancies exist here.

Her voice cracked like a whip. The map is clear. A soft wave of murmuring rolled through the courtroom. The foundation was laid. Daniel clicked a remote. The lights dimmed slightly. He played the night vision footage of the HOA patrolman. The same fellow now sitting in the front row, creeping along my fence, bolt cutters in hand, snipping the top wire before squeezing through like a possum with a mission.

When the clip of him getting zapped earlier played, the same officer slid so far down his seat he nearly disappeared under the bench. Someone behind me snorted, trying not to laugh. Daniel let the silence hang long enough to sting. This, he said calmly, is not an inspection nor a compliance check. This is trespassing and property destruction. The judge stared at the security man until he looked ready to melt. Mr.

Kellerman, she said, “Is that your client’s employee?” He shifted in place. “Yes, your honor.” It only got worse for him. Daniel pulled out his phone, connected it to the speaker, and pressed play. Bradley’s voice filled the room. We can make this all go away. A developer could purchase the northern strip. You walk away richer.

We keep the peace. Then my voice. You trying to buy me out? Bradley again. Just offering options. No court. No drama. A woman in the HOA row gasped. Another whispered Bradley, what did you do? Judge Hart leaned forward. Mr. Sloan, were you attempting to negotiate a land acquisition while simultaneously preparing to litigate the property owner? Bradley opened his mouth, but nothing came out. The judge looked like she wanted to hit him with the gavvel itself. Daniel wasn’t finished.

He lifted the last folder, the one I’d gotten from the surveyor friend, and opened it with the care of a man unveiling a coffin lid. “This,” he said, placing the developer sketch on the screen, “is the real motive.” The courtroom leaned forward. The sketch was simple but damning.

A feeder road cutting clean through my northern pasture, running straight into a planned expansion zone. And then Daniel pointed at the bottom corner. Your honor, note the date on this blueprint. March 12th, he paused. That is 2 months before Mr. Banner received his first violation letter. A wave of realization swept across the room.

They didn’t discover a violation. Daniel said they manufactured one to clear the path for this expansion. Judge Hart stared at the blueprint like it had personally insulted her mother. She removed her glasses slowly, folded them, and set them down. That, she said, is premeditated misuse of authority. Then she looked straight at Bradley. In Texas, Mr.

Sloan, we do not steal land with paper anymore than we do with wire fences. You are fortunate Mr. Banner only used electricity. A few ranchers behind me murmured in agreement. One even let out a quiet, “Amen.” The courtroom held its breath as Judge Hart lifted her verdict. “Mr. banner. She said, “Your fence is fully legal under the Texas Farm and Ranch Land Protection Act. Your land lies outside the HOA’s jurisdiction.

You are awarded 135,000 in damages, including legal fees, repairs, and emotional distress.” Bradley closed his eyes like someone had hit him with a shovel. As for the Clear Hillacres HOA, the judge continued, you are hereby ordered to issue a formal public apology and are permanently barred from any further regulatory attempts on Mr. Banner’s property. She paused, letting her next words cut deep. And Mr.

Sloan, your conduct will be referred to the district attorney for review. A hush fell over the entire courtroom. Daniel leaned over to me, voice just above a whisper. Told you the boots work. I almost smiled. Almost. The courthouse dust had barely settled by the time Daniel and I stepped back outside. The sky was wide and high, that bold Texas blue that makes a man feel like the world’s bigger than his problems.

A breeze kicked up, warm and steady, carrying the faint smell of cedar and distant hay. Daniel clapped a hand on my shoulder. “You did good, Hermono.” “You, too,” I said. He grinned. “Didn’t I tell you the boots work?” I shook my head, but I couldn’t keep the smile from tugging at my mouth. We said our goodbyes. Daniel climbed into his Silverado and rumbled down the street. He didn’t look back. He didn’t need to.

Some men leave like they know their works done right. I headed home, the road unwinding under my tires just the way it always had, like a living memory. But the ranch felt different when I pulled into the driveway. Not bigger, not grander, just steadier. Like it had planted its boots into the dirt and said, “This land stands.

” When I stepped onto the porch, my old dog, Duke, lifted his head, tail thumping once like he was too dignified to show he’d missed me. I scratched his ears and dropped into my rocking chair. Sun was already sliding toward the horizon, painting everything in that honey orange glow only Texas seems to understand. For the first time in months, I breathed easy.

The fallout came fast. By the next morning, my email inbox looked like a busted seed bag. Messages spilling everywhere. Some were congratulations. Some were folks thanking me. Some were pure outrage at the HOA written in caps lock like someone’s uncle pounding the keyboard. But the ones that mattered came from people I’d never met. A rancher in Yano County wrote, “Clay, they’re trying the same stunt here.

Your case gives us hope.” A woman outside Waco said, “Thank you for standing up. My parents lost land to a developer in 98. Wish they had someone like you back then. And one message, one simple message came from a young rancher in a nearby county, Harold Kim. Mr. Banner, I think I need help. I called him.

Turned out Harold’s situation looked a whole lot like mine before things got loud. A new development creeping in. HOA stretching its wings, threatening letters, boundary confusion, quiet intimidation. So I invited him over. He arrived that Saturday. Skinny kid, maybe 26, hat too big for him, boots too new.

But his hands, his hands had the look of someone who worked the land. Blisters and grit in the knuckles. We walked to the north pasture as the evening sun laid down that golden blanket over everything. Duke trotted alongside us like he was supervising. Harold studied the fence line, the cedar post sunk deep, the reflective electric warning signs catching the light.

He took it all in without saying a word. Finally, he asked, “Did it scare you when they first came after you?” I thought about it not long. “No,” I said. “But I didn’t like it.” “Why not?” “Because it wasn’t a fair fight. They had paper, meetings, committees, folks who never touch dirt telling me what my land should be.

That’s the part that rubs raw.” He nodded slowly. “So, what did you do?” I tapped the fence post. this. I built a line they couldn’t cross, morally or legally. I didn’t start a war, son, but I didn’t let one roll over me either. He swallowed hard. I want to do what you did.

You will, I said, but you won’t do it alone. That night, Harold stayed for dinner. Cornbread, smoked brisket, pinto beans, the usual. He talked about his dad who passed the ranch to him. How the place wasn’t big but it was theirs. How he didn’t want to lose it to folks who saw it as a future amenity buffer. After he left, I sat on the porch again, staring out across the pasture lit silver by moonlight.

That’s when the idea took shape. Not loud, not sudden, just steady like fence wire being stretched tight. a network, a handful of land owners, sharing maps, evidence, advice, support, not to fight HOAs, but to stop the ones that got ideas above their station. Daniel loved it.

He drafted up templates, cease and desist letters, boundary affirmations, trespass notifications, all cleaned and legal. Pro bono, he said, for the cause. Denise from Channel 5 loved it, too. She did a whole segment titled The Fence Line Network: When Neighbors Stand Up for Their Land. Never expected a local reporter to make me sound like some kind of folk hero, but she did.

Within a month, we had four more ranchers join. An older couple fighting a buffer beautifification order, a goat farmer who caught HOA volunteers trimming his property without permission, and a Vietnam vet fed up with drones snooping over his barn. We met once a week, sometimes here, sometimes elsewhere, drank coffee, swapped stories, and passed around maps like battle plans.

And slowly something changed. Not the land, not the law. But the way folks saw themselves, less alone, more rooted. We called it the fence line network, and the name stuck. As for Clear Hill Acres, they folded faster than wet cardboard. The apology they tried posting at 2 o00 a.m. didn’t satisfy anyone, especially not Denise.

She aired a follow-up asking why an HOA with nothing to hide posted its apology while the rest of the state was asleep. Bradley Sloan resigned before a vote could eject him. Word traveled that no developer in Austin wanted to hire him again.

Something about being the guy who lost to a rancher with a solar powered zap fence. That’s a reputation you don’t shake off. About 6 weeks after the trial, I was walking my fence line at sunrise, the cold, crisp kind of morning that stings your lungs just enough to wake you up, when I saw a man and his little boy standing by the fence.

The boy couldn’t be more than six, juice box in hand, eyes wide like he was meeting a legend. “Daddy,” he whispered. “Is this the electric cowboy fence?” His dad laughed, embarrassed. “Yes, son. This is the one. I walked over, tipped my hat. Don’t worry, I said. It’s off for now. The boy squinted up at me.

Sir, did you really zap a whole neighborhood? I chuckled. No, son. I just reminded them where their neighborhood ends. The boy stared at me like I’d told him a secret of the universe. His dad nodded respectfully. We appreciate what you did. Folks around here needed to see someone stand their ground. We shook hands. They walked off.

the boy still chattering about electricity and cowboys and fences that made the news. I stood there a moment longer, watching the sunrise climb over the hills, lighting the land my grandfather had left me, the land I had fought for, the land that would stay banner land long after I was gone. The fence hummed faintly in the morning breeze, steady as a heartbeat. It wasn’t just wire and voltage anymore.

It was a promise, a line drawn in Texas dirt and a reminder to anyone who forgot that some land isn’t for sale, isn’t for taking, and sure as hell isn’t for an HOA to claim. Not now. Not

News

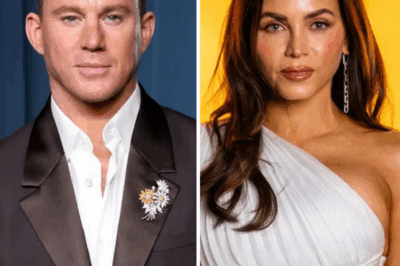

CH1 “At Long Last: The Final Breakdown of the Hollywood Split That Haunted ‘Magic Mike’”

When two Hollywood names once synonymous with chemistry and blockbuster success finally close the book on years of legal wrangling…

CH1 What Kind of Gun Is That? — Japanese Navy Horrified by the Iowa’s 16-Inch Shell RANGE

Philippine Sea. October 1944. A Japanese naval officer raises his binoculars, his hands trembling. On the horizon, four massive shapes….

CH1 Germans Couldn’t Understand How American VT Fuzes Destroyed 82% Of Their V-1s In One Day

For 80 terrifying days, London was on the brink of collapse under the V-1 buzz bomb attacks. What the public…

What devastating tragedy at your child’s school was easily preventable?

What devastating tragedy at your child’s school was easily preventable? My daughter has been getting followed home by the same…

What’s the hardest part about being born on a leap year?

My parents told everyone I died at birth, but I’ve been living in our soundproof basement for 16 years. They…

How did your father treat women?

How did your father treat women? My father made all the women in our house ask permission for every action…

End of content

No more pages to load