In the library, someone passed me a note that said, “Get out now. He has a gun.” The note hit my textbook while I was mid-sentence reading about the Cold War, and I watched the paper skid across my page like it had been thrown. My head snapped up, but there was nobody within 10 ft of me. The library was dead quiet, except for the hum of computers and Mrs.

Brennan’s fingers clicking on her keyboard at the circulation desk. I looked at the folded square of paper, my hand hovering over it, some instinct screaming not to touch it. The handwriting visible through the thin paper looked frantic, letters bleeding through in urgent darkness. When I finally unfolded it, the message was written in pencil pressed so hard the paper had torn in three places.

Get out now. He has a gun. My entire body went cold. I looked up again faster this time. My eyes darting to every face in the library. There were seven other people visible. Mrs. Brennan at her desk, totally absorbed in whatever she was reading. Two sophomore girls at a table near the windows, sharing earbuds and giggling at something on a phone.

a senior guy I recognized from the football team sleeping with his head on his arms three tables over. Behind the stacks, I could see movement. Someone walking between the shelves, but I couldn’t make out who. Near the study rooms at the back, a figure in a dark hoodie sat with their back to me, completely motionless.

And standing at the far end of my row, partially hidden by a bookshelf, was someone I didn’t recognize at all. A girl, maybe my age, staring directly at me with an expression of absolute terror. When our eyes met, she shook her head violently and mouthed something I couldn’t understand. Then she pressed a finger to her lips in a desperate shushing gesture before disappearing behind the shelf.

I grabbed my phone from my pocket, my hands shaking so badly, I almost dropped it. The note fell from my other hand and drifted under the table. Should I call 911? Should I pull the fire alarm? Should I run? Every option felt wrong. Felt like it would trigger something terrible. The person in the dark hoodie at the back hadn’t moved at all.

Hadn’t turned around. Just sat there like a statue. Were they the one with the gun? Or were they already dead? That thought hit me like ice water, and I stood up too fast, my chair screeching against the floor loud enough that everyone in the library looked over. Mrs.

Brennan’s head swiveled toward me with that annoyed librarian expression, about to say something about noise. The sophomore girls stopped giggling. The football player stirred, but didn’t wake up. The hooded figure turned their head slightly, just enough that I could see the pale profile of their face, but not enough to identify them. “I need to use the bathroom,” I said to Mrs. Brennan, my voice coming out weird and strangled.

She nodded and went back to her computer. I started walking toward the exit, forcing myself to move normally when every instinct screamed to run. I passed the sleeping football player and noticed his breathing was wrong, too shallow, his face too pale. Was he actually asleep or was something wrong with him? I kept walking.

The sophomore girls had stopped looking at their phone and were watching me with strange expressions. One of them, a blonde girl whose name I didn’t know, caught my eye and gave a tiny, almost imperceptible shake of her head. “Don’t leave,” she mouthed. Or maybe it was don’t move. I couldn’t tell. My heart was trying to beat out of my chest. I was three steps from the library door when someone grabbed my wrist from behind.

The grip was firm but not painful. Fingers wrapping around my arm like a handcuff. I spun around and found myself face to face with the girl who’d been hiding behind the bookshelf, the one who’d shaken her head at me. Up close, she looked sick with fear. Her skin pale and sweaty, her pupils dilated so wide her eyes looked black. Don’t, she whispered. If you leave, he’ll know.

He’ll start shooting. Her hand was trembling against my wrist, but her grip didn’t loosen. “Who?” I asked, barely getting the word out. “Who has the gun?” she glanced toward the back of the library, toward the figure in the dark hoodie who still hadn’t moved. “Him,” she said. “But he doesn’t know that I know. He thinks everyone’s calm.

If you panic, if you run, he’ll realize someone warned you. Then he’ll start early.” “Early? What do you mean early?” She pulled me sideways away from the door toward a section of shelves that created a small al cove hidden from most of the library. We crouch down between encyclopedias nobody used anymore for breath coming in short gasps.

He comes here every Wednesday during third period. He sits in the same spot. He waits until exactly 10:37. Then he stands up and starts shooting. I checked my phone. It was 10:28. We have 9 minutes. She continued, her voice shaking. I’ve been trying to figure out how to stop it. I’ve tried everything. Nothing works. He always does it. Always. I stared at her.

What are you talking about? This hasn’t happened yet. How do you know what he’s going to do? her eyes filled with tears. Because I’ve lived this day 63 times. Every time I wake up, it’s Wednesday morning again. Every time I try something different. Every time people die. You’re the first person who’s ever read my note. My brain couldn’t process what she was saying.

It sounded like something from a movie. Impossible and insane. But her terror was real. The note was real. And the figure in the dark hoodie was real. Sitting there like a coiled spring. I looked at my phone again. 10:29. Are you saying you’re stuck in a time loop? like the same day repeating. She nodded frantically. I know how it sounds.

I know you don’t believe me. But in 8 minutes, Cory Vance is going to stand up from that chair, pull a gun from his backpack, and open fire. He’ll shoot Mrs. Brennan first, then the two girls by the window. Then he’ll start working his way through the stacks. 17 people will be in this library by 10:37. 11 will die before the police breach the doors.

I’ve watched it happen over and over. I’ve tried calling 911 early, but he hears the sirens and starts shooting immediately. I’ve tried warning Mrs. Brennan, but she thinks I’m pranking and sends me to the office. I’ve tried pulling the fire alarm, but he shoots people in the chaos of evacuation. I look toward the back of the library. The hooded figure, Cory Vance, apparently still sat motionless.

You’re telling me that kid is going to commit a mass shooting in 8 minutes. She nodded. 7 minutes now. Why don’t you just tackle him? Take the gun before he can use it. I tried that on day 19. He shot me in the chest. I died in 45 seconds. She lifted her shirt slightly, showing smooth, unmarked skin. no scar because when I die, the day resets.

I wake up in my bedroom at 6:30 a.m. and have to live it all again. I pulled back from her, my mind rejecting everything she was saying. This was crazy. She was crazy. But her eyes held something beyond fear, a kind of exhausted desperation that felt too genuine to be faked.

And even if she was delusional, what if she was right? What if in 6 minutes someone started shooting? I need to leave, I said, standing up. I need to get help. She grabbed my arm again. If you leave and he sees you running, he’ll panic and start early. If you call 911 from here, he’ll hear you. If you warn Mrs. Brennan, she’ll confront him and he’ll shoot her immediately instead of waiting. I’ve tried every variation.

The only way to stop this is to get his gun before 10:37 without him knowing we’re coming for it. I checked the time. 10:31. How are we supposed to do that? She pulled out her own phone and showed me photos, dozens of them, showing different angles of the library. In this loop, I’ve been documenting everything. Cory’s backpack is under his chair.

The gun is in the front pocket, loaded with 15 rounds. He keeps his hand near it, but he’s not holding it yet. If we can create a distraction, get him to look away, one of us might be able to grab the bag. I looked at the photos, my hands shaking. They showed the hooded figure from multiple angles, always in the same position, always at the same table.

In one photo, the backpack was clearly visible under the chair, dark blue with a Nike logo. What kind of distraction? She bit her lip. That’s what I’ve been trying to figure out. Every distraction I’ve tried either doesn’t work or makes him suspicious. We need something that pulls his attention completely away but doesn’t seem threatening.

I looked around the library, my mind racing, the sophomore girls by the window, the sleeping football player, Mrs. Brennan at her desk, the person moving between the stacks who I still couldn’t identify, and us hiding between shelves with 6 minutes until a massacre that might or might not be real. “What if you’re wrong?” I asked.

“What if this is all in your head and I help you attack an innocent student?” Her expression hardened. Then I’ll wake up tomorrow morning and live this day for the 64th time and you’ll never remember this conversation. But you’ll be dead. Everyone will be dead. I checked the time. 10:33 4 minutes. My heart was beating so fast. I felt dizzy. What’s your name? I asked. Sage Winters junior transfer student from Colorado.

Nobody here knows me, which is why nobody believes me when I try to warn them. She showed me her student ID, proving at least that part was true. What’s your name? Avery Demis. Sophomore. I’ve been going to this school my whole life and I’ve never seen anything like this. I looked toward Cory Vance’s motionless figure. He hadn’t moved at all. Hadn’t checked his phone.

Hadn’t done anything that suggested he was counting down to violence. He just sat there. What makes you so sure he’s going to do it this time? Maybe this loop is different. Sage’s laugh was bitter. I thought that, too. On day 37, he never showed up to the library. I thought maybe the loop had changed. Maybe I’d somehow prevented it by existing differently that morning.

Then at 10:37, he came through the back entrance instead of the front. He’d changed his approach, but not his plan. He killed 14 people that day because I wasn’t ready for him. Since then, I’ve learned that small things change, but the big event stays the same. He always comes. He always sits there. He always starts at 10:37.

The only question is whether I can finally stop him. I looked at my phone. 10:34 3 minutes. We need to move now. What’s the plan? She pulled me deeper into the stacks toward the back of the library where Cory sat about 30 ft away. We need to split up. You create a distraction at the front of the library.

Something loud but not alarming. Drop a stack of books. Knock over a chair. Anything that makes him turn around to look. While he’s distracted, I’ll come from behind and grab his backpack. I’ll run to the emergency exit and throw it outside before he realizes what happened. It was a terrible plan with a thousand ways to fail, but I couldn’t think of anything better. And the clock was ticking.

10:35. 2 minutes. I started moving toward the front of the library, trying to look casual, my legs feeling like they’d been filled with sand. Mrs. Brennan looked up as I passed her desk. “Everything okay, Avery?” I nodded, not trusting my voice.

The sophomore girls were watching me again, and this time, I realized they both looked scared, like they knew something was wrong, but couldn’t articulate what. The sleeping football player still hadn’t moved. I reached the section of shelves nearest the door and started pulling out books at random, stacking them on a nearby table, building a tower that I planned to knock over at exactly the right moment. My phone showed 10:36.

One minute, I looked toward the back of the library and saw Sage moving into position, creeping along the far wall where Cory couldn’t see her approach. She caught my eye and gave a slight nod. I looked at Cory Vance, really looked at him for the first time. He was maybe 17, thin with pale hands resting on the table in front of him.

His hoodie was pulled up, but I could see part of his face in profile. He looked tired more than dangerous, his shoulders hunched like he was carrying unbearable weight. For a second, I felt doubt. What if Sage was wrong? What if this was all some delusion and we were about to assault an innocent, depressed teenager? But then I saw his hand move slightly, drifting toward the backpack under his chair, and my doubt evaporated.

10:37 The clock on the library wall clicked over to the exact minute Sage had predicted. Cory’s entire body language changed in an instant. his shoulders straightening, his hand reaching down toward the backpack with sudden purpose. I didn’t think. I just swept my arm across the table and sent 15 books crashing to the floor in a cacophony that echoed through the silent library.

Everyone turned to look. Mrs. Brennan stood up from her desk. The sophomore girls jumped in their seats. The football player finally lifted his head and Cory Vance twisted around in his chair to see what had caused the noise. In that second of distraction, Sage lunged forward and grabbed his backpack, yanking it out from under his chair and sprinting toward the emergency exit.

Cory’s head whipped back around and he saw her running with his bag. His expression transformed from confusion to rage to panic in the space of a heartbeat. “No!” he shouted, launching out of his chair and chasing after Sage. She was faster, hitting the emergency exit door with her shoulder and bursting through it into the parking lot beyond, the alarm immediately shrieking.

Corey ran after her and I ran after him. My brain screaming that this was insane, that I should let adults handle it. But my body already in motion behind me, I heard Mrs. Brennan yelling questions nobody was answering. We all burst into the parking lot, bright autumn sun blinding after the dim library.

Sage was 20 ft ahead, running flat out toward the faculty parking area, the backpack clutched against her chest. Cory was 10 ft behind her, gaining ground, screaming wordless rage. I was behind him, my lungs burning. No idea what I’d do if I caught him, but running anyway. said it. Sage reached a faculty car and threw the backpack underneath it, then kept running.

Cory slid to a stop, dropping to his knees to crawl under the car and retrieve his bag. That’s when I caught up to him. I didn’t plan what to do next. I just drove my shoulder into his side as hard as I could. The impact sending both of us sprawling across the asphalt. Pain exploded in my elbow and hip as I hit the ground.

Cory tried to scramble away, but I grabbed his hoodie and held on with every ounce of strength I had. He twisted around, and I saw his face clearly for the first time. He was crying, tears streaming down his face while he fought to get free. His expression a mixture of grief and fury that looked almost inhuman. Let go, he screamed. You don’t understand. I have to. I have to do this. I didn’t let go.

I held on while he thrashed and hit me and screamed about how everyone would finally understand how they’d finally see the truth. Then Sage was there, pulling out her phone and calling 911 while Cory and I wrestled on the ground. Then the football player appeared, no longer sleeping or pale, running from the library to help hold Cory down.

The sophomore girls came out filming everything on their phones. Mrs. Brennan emerged, her face pale with shock, asking what was happening, why we were fighting, what was in the backpack. Then the security officer from the front office arrived, speaking urgently into his radio, pulling me away from Cory with professional efficiency.

Then police sirens in the distance getting louder. Cory stopped fighting. He just lay on the asphalt crying while two officers handcuffed him and read his rights. A third officer retrieved the backpack from under the car, opened it carefully and pulled out a black handgun that looked too real, too heavy, too final.

The entire school went into lockdown. They evacuated the library and searched every inch. They found ammunition in Cory’s locker, a manifesto on his phone, a list of names he’d been planning to target. Sage and I were separated and questioned by different detectives.

I told them everything about the note, about Sage’s warning, about the time loop story that sounded insane in the bright fluorescent lights of the principal’s office. The detective, a woman named Lieutenant Angela Price, listened without interrupting. Then she asked to see my phone. She examined the timestamps of my texts, my location history, building a timeline of my movements.

Did you know Cory Vance before today? No, I’d never seen him before. Had you ever spoken to Sage Winters before she gave you the note? No, I didn’t know she existed. Lieutenant Price made notes. You understand how this looks? A transfer student nobody knows somehow predicts a school shooting and convinces you to help her stop it. I understand it sounds impossible, but she was right.

She knew exactly when he’d do it, exactly where he’d sit, exactly where the gun would be. How would she know that unless she’d seen it before? Lieutenant Price didn’t answer. She just asked more questions. How did Sage seem when you first saw her? Terrified, like she’d been through something traumatic.

Did she explain how she knew about Cory’s plan? She said she’d lived the day 63 times, like a time loop. The detective’s expression didn’t change. Did you believe her? I didn’t know what to believe, but I believed she believed it, and I believed someone was going to get hurt if we didn’t do something. After 2 hours of questioning, they let me call my parents. My mom arrived 20 minutes later, her face tight with fear and anger and relief.

She hugged me in the hallway outside the office while I tried to explain what had happened. None of it made sense even to me, the person who’d lived through it. They kept the school in lockdown for 6 hours while bomb sniffing dogs searched every room and FBI agents interviewed potential witnesses. I sat in the cafeteria with hundreds of other students.

All of us scrolling through social media watching the news coverage. Active shooter plot foiled at Westfield High. Two students hailed as heroes. Disturbing manifesto found. Every news outlet showed the same photo of Cory being led to a police car in handcuffs. His face twisted with rage and tears.

My phone exploded with texts from people I barely knew, asking if I was okay, asking what happened, asking how I’d known. I didn’t answer any of them. I just sat there feeling numb and confused and terrified about what could have happened if Sage had been wrong. if her time loop story had been a delusion, if we’d attacked an innocent person. But she hadn’t been wrong. The gun had been real. They released us at 4:30 p.m.

My mom drove me home in silence, occasionally reaching over to touch my arm like she needed to confirm I was real. At home, my dad was waiting, having left work early when he heard the news. He hugged me hard enough to hurt, and didn’t let go for a full minute. “Are you okay?” he kept asking.

“Are you hurt? Did anyone hurt you?” “I’m fine,” I kept saying. But I wasn’t fine. I kept seeing Cory’s face, the grief and rage mixing into something that looked like madness. I kept hearing Sage’s voice saying she’d live this day 63 times. I kept thinking about the 17 people who would have been in that library if she hadn’t stopped it. That night, I couldn’t sleep.

Every time I closed my eyes, I saw the gun being pulled from the backpack. I gave up at 2 a.m. and went to my computer. I searched for everything I could find about Cory Vance. Social media profiles that had been quickly deleted but existed in cached versions. A freshman photo from the school website showing a smiling kid who looked nothing like the person I’d fought in the parking lot.

Posts from middle school showing a boy with friends playing basketball looking normal. Then something changed. His post became darker, angrier, filled with complaints about being invisible, about how nobody cared, about how they’d all regret ignoring him. The last post from 2 weeks ago just said, “Soon everyone will remember my name.

I found his list of grievances leaked by someone with access to the police evidence. He’d been bullied, failed classes, lost friends. His parents had divorced, his girlfriend had left him. None of it justified what he’d planned, but it explained the desperation in his eyes when I’d tackled him. Then I searched for Sage Winters. There was almost nothing. A transfer enrollment notice from 6 weeks ago.

No social media I could find, no photos except one from a Colorado newspaper showing her winning a debate competition 2 years ago, smiling at the camera like nothing was wrong. I tried to find any evidence supporting her time loop story. Obviously, I found nothing. Time loops weren’t real. She must have found out about Cory’s plan some other way.

Maybe she’d seen something on his social media. Maybe someone had told her. Maybe she’d been stalking him. The rational explanations made sense, but didn’t explain how she’d known the exact time, the exact location, the exact details of what would happen. At 3:00 a.m., my phone buzzed. A text from an unknown number. It’s Sage.

Are you awake? Can we talk? I called her immediately. Her voice sounded exhausted, drained in a way that went beyond physical tiredness. The police finally let me go home. They questioned me for 6 hours. They think I’m either a hero or an accomplice. They’re trying to figure out how I knew. I didn’t tell them the truth because nobody would believe it.

I didn’t tell them either. She continued about the time loop. I just said I’d overheard Corey talking about bringing a gun to school and confronted him in the library. It’s a lie, but it’s a lie they can accept. Are you okay? Her laugh was hollow. I don’t know. I’ve spent two months living the same day over and over.

Today felt different because we actually stopped it. But I don’t know if it’s real or if I’m going to wake up tomorrow morning and it’ll be Wednesday again. If the loop resets, I’ll remember this conversation, but you won’t. You’ll forget we ever worked together. The thought was disturbing on a level I couldn’t articulate.

How did it start? The time loop. She was quiet for a moment. I woke up on Wednesday morning 6 weeks ago and went to school like normal. Third period, I was in the library studying when Cory stood up and started shooting. I died on the first day. I was trying to run and he shot me in the back. I bled out on the floor in about 3 minutes.

It was the worst pain I’ve ever felt. Burning and cold at the same time. Then I woke up in my bed at 6:30 a.m. on Wednesday morning again. At first, I thought it was a dream, but everything was identical. Same breakfast, same clothes, same conversations. I went to school and at 10:37, Cory started shooting again.

That time, I’d already run to the office to tell them about the threat. They got the police there in time to stop him, but he killed four people before they arrived. Then I woke up Wednesday morning again. She’d lived through variations of the massacre 63 times, she explained. Sometimes she got everyone killed trying to evacuate. Sometimes she got herself killed trying to be a hero.

Sometimes she saved most people, but a few still died. Every night when she went to sleep, the day would reset, and she’d wake up Wednesday morning again with all her memories intact. Day after day after day of watching people die, trying different strategies, failing in new and horrible ways. Today was the first time nobody had died.

Today was the first time someone had actually believed her enough to help. But she still didn’t know if the loop was broken or if tomorrow morning she’d wake up and have to do it all over again. We talked for 2 hours until the sun started coming up and exhaustion pulled both of us towards sleep. If I wake up and it’s Wednesday morning again, I’ll find you, she said. I’ll show you this text thread.

I’ll prove we’ve done this before. Okay, I said. And if it’s Thursday, then maybe I’m finally free. And I woke up on Thursday morning to my mom shaking my shoulder, her face concerned. You slept through your alarm. Do you want to stay home from school today? After everything yesterday, nobody would blame you. I checked my phone.

Thursday, October 12th, not Wednesday. The loop had broken. I texted Sage immediately. It’s Thursday. You did it. You broke the loop. Her response came back 30 seconds later. I’m crying. I’ve been awake since 6:30, terrified it would be Wednesday again. It’s really over. School was surreal.

Classes were cancelled for the day, but they’d opened the building for counseling services and community gathering. Half the students showed up anyway, needing to be together, needing to process what had almost happened. The library was closed, yellow police tape across the entrance, but the rest of the building felt almost normal except for the armed police officers stationed at every entrance.

Sage and I met in the cafeteria where counselors had set up tables with coffee and donuts and boxes of tissues. She looked different in daylight, younger without the terror that had made her seem ancient. We sat together while other students whispered and pointed, everyone knowing we were the ones who’d stopped it, but nobody knowing exactly how. The sophomore girls from the library came over to thank us.

Their names were Zara and Nicole, and they’d been 12 feet from where Cory would have started shooting. “You saved our lives,” Zara said, crying. “I don’t know how you knew, but thank you.” The football player, whose name was Devon, shook my hand hard enough to hurt. “I wasn’t sleeping,” he admitted.

“I’d taken three benadryil because I’d been up all night studying. I was barely conscious when you started running. By the time I realized what was happening, it was almost over.” The news crews showed up around noon, setting up outside the school, trying to interview students as they left. I avoided them, but Sage didn’t.

I watched on my phone as she gave a carefully crafted interview about overhearing concerning statements and trusting her instincts. She never mentioned the time loop. She never mentioned living through the massacre 63 times. She just positioned herself as alert and cautious, a good citizen who reported potential danger. The interviewer called her a hero. She flinched at the word.

The police arrested two of Cory’s friends that afternoon, students who’d known about his plan and said nothing. The DA charged them as accessories, arguing that their silence made them complicit in the attempted massacre. One of them, a senior named Derek, gave an interview from jail, saying he’d thought Cory was joking, that everyone talked about revenge fantasies, but nobody actually followed through. He’d been wrong. Cory had been serious.

The school board called an emergency meeting to review security protocols. They announced metal detectors would be installed, security officers would be armed, and a behavioral threat assessment team would evaluate students showing warning signs. Parents formed committees to demand action to ensure something like this could never happen again.

News outlets ran investigations into how Cory had acquired the gun, how he’d planned for months without anyone noticing, how the system had failed to identify a student in crisis. Everyone wanted answers, wanted someone to blame, wanted to believe they could prevent the next tragedy if they just implemented the right policies.

Nobody wanted to acknowledge that sometimes there were no warning signs you could act on until it was too late. Sage and I had been lucky. We’d stopped it. But how many other times had there been no one like Sage to warn people? A week later, the FBI released their full report on Cory’s plan.

He’d been radicalized by online communities that glorified school shooters that treated them as martyrs and heroes. He’d studied previous attacks, learned from their tactics, planned his own with meticulous detail. The manifesto on his phone laid out his grievances in 50 pages of bitter rambling fury about being ignored, being rejected, being invisible.

He’d wanted to make people remember him, to force them to acknowledge his existence through violence since they wouldn’t acknowledge it through anything else. The psychology experts called it a narcissistic crisis combined with suicidal ideiation. The news called it evil. I didn’t know what to call it. I just knew that seeing his face in those photos made me feel sick with a mixture of rage and pity I couldn’t reconcile.

Sage and I started meeting for lunch every day, drawn together by the shared experience nobody else could understand. She told me more about the time loop, about the variations she’d lived through, about the people who’ died in different timelines. Mrs. Brennan had died first in most loops, shot in the chest before she could even scream.

Zara and Nicole died together in nearly every version, holding hands while they tried to hide behind their table. Devon had survived in some loops by pretending to be dead, lying still among bodies while Cory searched for more victims. In the worst loop, day 38, Cory had killed everyone in the library before turning the gun on himself.

And Sage had survived by hiding in the bathroom, listening to gunfire, and screaming for 20 minutes. She’d lived with that memory, with all those memories, and now had to pretend it was all hypothetical rather than experience trauma. We talked about whether she should tell someone the truth, whether there was any way to explain the time loop that wouldn’t result in forced psychiatric evaluation. She decided against it.

“They’d never believe me,” she said. They’d think I had some kind of precognitive psychosis or that I’d been planning this with Cory and got cold feet. The only truth they can accept is the one I told them. I overheard him. I warned you. We stopped him together. It’s close enough to real that it works. But I know what really happened.

I remember every version of that day. I remember dying. I remember watching other people die. I remember the smell of blood and gunpowder. I remember things that never happened in this timeline but did happen in 62 others. How do you live with that? I asked. How do you move forward when you remember experiences nobody else shares? She shrugged. I don’t know yet.

I’m figuring it out day by day. Every morning when I wake up and it’s a new day instead of Wednesday again, I feel relieved, but I also feel like I’m waiting for it to snap back, for the loop to start again. What if it wasn’t really broken? What if I’m still trapped and just experiencing a longer iteration before it resets? The paranoia in her voice was painful to hear. I reached across the cafeteria table and took her hand.

If it resets, we’ll stop him again and again. As many times as it takes. She smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes. I’m tired, Avery. I’m so tired of being afraid. Cory went to trial 8 months later. His defense attorneys tried arguing diminished capacity, that he’d been in a dissociative state, that he’d been influenced by online radicalization beyond his control.

The prosecution presented his manifesto, his weapons cash, his meticulously detailed plan. They called Sage and me as witnesses. We testified about finding the note, about stopping him in the parking lot, about the gun in his backpack. Cory sat at the defense table looking smaller than I remembered, his face blank, showing no emotion as witness after witness described the massacre he’d planned. When it was my turn to testify, the prosecutor asked me to describe the moment I’d tackled him.

I remembered his tears, his screaming about how everyone would finally understand. The jury deliberated for 4 hours before finding him guilty on 17 counts of attempted murder, weapons charges, and conspiracy to commit terrorism.

The judge sentenced him to 45 years in prison, saying that his youth didn’t excuse his actions, that his plan had been sophisticated and deliberate, that he represented a continuing danger to society. Cory showed no reaction to the sentence. He just stared at the table while baiffs led him away in shackles. Sage and I left the courthouse together, both feeling hollow rather than vindicated. The trial was over, but the weight of what had almost happened would never fully lift.

Three years later, I graduated from Westfield High and went to college across the country, needing distance from the place where I’d almost died, even though I technically hadn’t. Sage went to a different school, but we stayed in touch, texting occasionally, meeting up during holidays when we were both home. She’d started seeing a trauma therapist who specialized in PTSD, though she still didn’t tell anyone about the time loop. Some experiences were too strange to share, even with professionals trained to believe the unbelievable.

She seemed better, more grounded, though she admitted she still had nightmares about waking up Wednesday morning again. The loop had been broken for 3 years, but the fear that it could restart never fully disappeared. I had my own nightmares.

Dreams where I didn’t get to the library in time, where Sage’s note arrived too late, where Cory succeeded in his plan, and I watched people die while I stood frozen and useless. We gave interviews occasionally when journalists wanted to revisit the story. when other schools experienced tragedies and reporters needed examples of prevention that had worked. We never mentioned the time loop.

We stuck to the official story about overhearing a threat and taking it seriously. But between us in private conversations, we talked about the other timelines, the ones where we’d failed, where people had died, where the outcome had been different. Sage carried the memories of 63 Wednesdays that nobody else remembered, deaths that had been erased when the loop reset but lived on in her mind. Sometimes she’d tell me about people I’d never met.

Students who’d died in other timelines, describing their last moments with painful detail. I’m the only person who remembers them, she’d say. In this timeline, they survived because they weren’t in the library that day, but in others, they died. I remember their faces, their screams, their final words.

Doesn’t that mean something? Doesn’t that mean I owe it to them to remember? I didn’t have answers for her. I just listened and tried to understand what it meant to carry memories of events that had been erased from everyone else’s reality. 5 years after the incident, Sage called me at midnight, her voice shaking. I need to tell you something I’ve never told anyone. I’m getting married next month. His name is Julian.

He’s amazing and kind, and he makes me feel safe, but I’ve never told him about the time loop. He knows about Westfield. Everyone knows about Westfield, but he thinks it happened the way the news reported. How do I marry someone when I’m keeping the most fundamental truth about myself hidden? Do I tell him? Do I risk him thinking I’m insane? or do I carry this secret forever knowing there’s a part of me he’ll never fully understand. I thought about it before answering.

You tell him, I said, not because he deserves to know, but because you deserve to be fully known by the person you’re spending your life with. The risk is worth it. If he can’t handle the truth, better to find out now than carry that weight alone forever. She told Julian 3 days later.

He called me afterward asking if the time loop story was real or if Sage was experiencing trauma-induced false memories. I confirmed it was real, at least real to her, and that her memories of those other timelines were as vivid and detailed as any normal memory. Julian struggled with it for a week, researching time loops and quantum physics, and trying to find a framework that made sense.

Eventually, he called Sage and told her it didn’t matter whether he fully understood or believed the mechanics of what had happened. What mattered was that she’d experienced something traumatic, that she carried memories of events others didn’t share, and that he loved her regardless of whether those memories were literal or psychological.

They got married in a small ceremony where I stood as sage’s maid of honor. Both of us crying through the vows, both thinking about how close she’d come to never experiencing this day in any timeline. 10 years after Westfield, they released Cory’s prison interviews to the public. He’d spent a decade behind bars and had participated in multiple therapeutic programs, working to understand what had driven him to plan mass murder.

In the interviews, he expressed remorse that sounded genuine, describing how his anger and narcissism had blinded him to the humanity of his intended victims. How the online communities had warped his thinking until violence seemed like the only solution to his pain. He’d never be released, the interviewer noted. He’d spent his entire life in prison for crimes he’d attempted but not completed.

Did he deserve forgiveness? The question sparked fierce debate on social media, with some arguing that attempted murder deserved the same punishment as actual murder, while others suggested his youth and subsequent remorse should matter. Sage and I watched the interviews together at her house. Julian in the next room giving us space. She’d wanted to see him to hear him explain after all these years.

At the end, when the interviewer asked Cory if he had anything to say to the students he’d planned to kill, he looked directly into the camera. I’m sorry feels inadequate for what I intended to do. I was in so much pain that I wanted everyone else to hurt, too. But pain doesn’t justify evil. I’m grateful I was stopped before I could hurt anyone. I think about the people I would have killed every single day.

I see their faces in my mind, imagining what they’ve done with the lives I try take. One girl would have graduated valadictorian. Another plays college basketball now. A boy became a doctor. They’re all living because two students were brave enough to stop me. I don’t deserve their forgiveness and I’m not asking for it. Just want them to know that my failure to kill them.

The only thing in my life I’m proud of. Sage turned off the interview and sat in silence for several men. I believe him. I don’t know if it matters whether I he’s in prison either way. Can’t hurt anyone anytimes. I wonder about the core other timeline ones where he succeeded.

Those realities that don’t exist anymore killed 11 peep self. He never had a chance to feel remorse. Throw to understand what he’d done. This Corey one in our timeline to live with what he almost did. That’s its own kindness. 15 years after Westfield, I returned for a memorial vacation. School had built a small garden with a plaque on prevention of tragedy, thridge, and vigilance.

Sage’s name and mine were engraved along with the date and a quote. Sometimes heroism is stopping the terrible thing before it begins. We stood together at the ceremony while the principal gave a speech about school safety and responsibility. Students who’d been toddlers when it happened, listened polite, not fully understanding that they were standing 20 ft from where 11 people would have died, not for a note passed in the library.

After the ceremony, Sage and I walked to the library, which had been renovated, but still occupied the same space. We stood at the table where I’d been studying 15 years ago, where a note had ever think about how many other people might be living through time loops, sage asked.

How many other tragedies might be getting prevented in resets we don’t remember? How much worse could our world be if not for peaked in their own, learning from mistakes nobody else knows? I thought about it.

The idea that reality might be stantly being erected by people stuck in loops optimizing outcomes we took for granted as singular events. It was terrifying and comforting at the same time. We don’t know, I said. We can’t know. We can only be grateful for the timeline we’re in and try to prevent the tragedies we can see coming. Sage nodded and placed her hand on the table where the note had landed. Thank you for believing me that day.

Thank you for running when I needed you to run. I put my hand over hers. Thank you for living through Wednesday 63 times until you figured out how to save us all. 20 years after Westfield, Sage and Julian have two children who will never know how close they came to not existing.

I’m their godmother, present at their births, watching them grow in a timeline that almost didn’t happen. Sometimes I look at those kids and think about the 11 people who died in other timelines, the families they would have had, the futures that were erased when the loop reset. Sage carries those memories alone, the weight of knowing she’s the only person who remembers them.

But she carries it day after day, living fully in the timeline she fought to create. Grateful for every Wednesday morning that brings a new Thursday. Thanks for watching till the end.

News

My husband is cheating on me but I don’t care, my mother thinks I’m insane.

My husband is cheating on me, but I don’t care. My mother thinks I’m insane. I told my husband from…

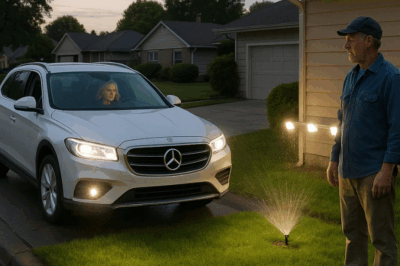

HOA Karen Kept Cutting Across My Lawn — So I Set Up a Trap She’ll Never Forget

Anna Edwards thought my corner lawn was just decoration on her racetrack. To her, my $300 retirement grass in Maple…

My stepsister said, “You’re not invited to the family reunion,” but then nobody…

My stepsister said, “You’re not invited to the family reunion, but then nobody showed up to hers. It started 3…

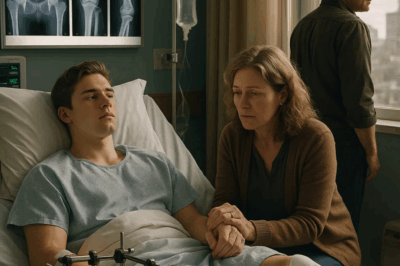

My cousin thought the cliff dive was funny. I shattered 14 bones. Now I’m shattering his life.

My cousin thought the cliff dive was funny. I shattered 14 bones. Now I’m shattering his life. The orthopedic surgeon’s…

CH1 How One Farmer’s “Crazy Trick” Shot Down 26 Japanese Zeros in Just 44 Days

On October 9th, 1942, 20,000 ft above a jungle island called Guadal Canal, a 22-year-old American pilot named Marian Carl…

The relatives picked out a restaurant for Granny… and forgot it has to be paid for.

I was taking plates down from the shelf for the guests when I caught a snatch of conversation in the…

End of content

No more pages to load