What devastating tragedy at your child’s school was easily preventable? My daughter has been getting followed home by the same three seniors ever since she started freshman year 5 months ago, and the school’s only response has been, “Boys will be boys.” Well, last Monday, I was eating lunch at work when I got a series of frantic texts from Laya.

They’re in the girls’ bathroom. They’re trying to climb into my stall. Please help, Dad. I’m so scared. I knocked my chair over getting up. Phone already dialing the school as I sprinted through the parking lot. Secretary’s desk. How can my daughter is in the bathroom? Three seniors are climbing into her stall. The secretary paused.

Which bathroom? I put the key in and started speeding immediately. Third floor, I think. I don’t know. Just find her. The secretary wasn’t speaking. Her name is Laya Clarks. They’re attacking her right now. Sir, she started. Unfortunately, the rules state I cannot leave my secretary desk unattended. And the principal is unavailable on her lunch break right now.

I practically screamed this next part into my phone. Are you stupid? What are you talking about? Go to the bathroom now. Sir, she said like she was talking to a child. Please refrain from using vulgar language. They’re climbing into my daughter’s stall. I’ll make a note for when the principal returns. I hung up, realizing I was dealing with a human robot.

Laya hadn’t texted in 4 minutes now. 8 minutes later, I abandoned my car sideways in the bus lane and sprinted through the front doors of the school. The secretary looked up from her computer, mouth opening to speak about sign-in procedures, but I was already past her. I ran to that bathroom faster than I’d ever ran in my life.

But when I got to it and went to open it, my worst nightmare came true. It was locked from the inside. The boys must have gotten the keys to deliberately do this. I pressed my ear against the door and I could hear them in there with her. Laya was crying. Her clothing was getting ripped and suddenly her crying turned into muffled screaming like someone covered her mouth.

I threw my shoulder against the door, but these were the new doors they’d installed after the shooting four years ago. Reinforced steel frames. The door didn’t even shake. Laya, I’m here. I grabbed a chair from the hallway and swung at full force. The chair shattered into pieces while the door stayed perfect. The fire extinguisher was heavier.

I hammered it against the lock mechanism over and over, metal ringing through the hallway. But these doors were doing exactly what they were designed to do. By now, the secretary had climbed the stairs, panting and red-faced. “Sir, you’re destroying school property. I’m calling security.” “Give me the key,” I yelled. She visibly shook at how angry I was.

“I don’t have bathroom keys, sir,” she said. Only the principal has those and she’s By the time she finished her sentence, I was running to her office. I finally reached it and through the window I saw her at her desk eating a salad while scrolling through her phone. I pounded on her door hard enough to shake the wall.

She looked up slowly, held up five fingers, mouthed 5 minutes, pointed to her food, and went back to scrolling. That’s when the security guard appeared behind me, hand on his radio. Sir, you need to calm down. But I didn’t. I picked up another chair. The principal saw me raise it, and her eyes went wide.

I swung the chair through her window. Glass exploded everywhere. She screamed, dropping her salad. I reached through, unlocked her door from inside, blood from the glass cuts dripping on her carpet. Sir, stop. The security guard grabbed my arm, but I shoved him off and went straight for her desk, yanking open drawers until I found the key ring. You’re insane.

The principal shrieked. I’m calling the police. I ran back to the bathroom, keys jangling, leaving bloody handprints on the walls. But when I got there, the door was already open. The boys were gone, and my dear Laya was curled on the floor, her skirt torn, her lips bruised, her hair covered in white sticky liquid, and her shirt unbuttoned and bra torn.

I immediately pulled out my phone to call 911, kneeling beside Laya, taking off my jacket to wrap around her when the principal rushed in with the security guard. “You assaulted me.” The principal’s voice was shrill. “Jim, he could have killed me with that chair.” I was talking to the dispatcher, one hand holding the phone, the other stroking Yayla’s cheek as she choked out blood and tears.

The principal kept going, pacing now, gesturing wildly. You’ve traumatized my entire staff. She pulled out her own phone. Every student on this floor saw you acting like a maniac. That’s 200 children who will need counseling. The security guard was filming everything. This is going to be on the news, the principal continued, now talking to someone on her phone.

A parent going psychotic, destroying property, creating an unsafe learning environment. Our insurance doesn’t cover parental attacks. The superintendent is going to Yes. Hello. She suddenly interrupted herself. We have a violent intruder who threatened me with a weapon. She gave my physical description and described the premeditated assault.

She never mentioned the three boys or why I did what I did. When the police arrived 4 minutes later, she pointed at me first. That’s him, the one who attacked me. Two officers moved toward me while two more pushed past to get to Laya. The first officer put his hand on my shoulder and started guiding me away from my daughter.

I tried to explain about the three boys, but he just said we’d talk at the station. My hands were still dripping blood from the window glass onto the bathroom floor. The paramedics rushed in with their bags and went straight to Laya who was still curled up on the cold tiles. They started checking her over and one of them called for a gurnie while I watched from the doorway with the officer’s hand still on my shoulder.

The principal was already talking loudly to another officer about how I’d gone crazy and attacked her office. She kept pointing at me and using words like violent and unstable while Jim held up his phone to show the video he’d taken. Nobody asked about the three boys or why I’d been trying to get into this bathroom in the first place.

The paramedics lifted Laya onto the gurnie and covered her with a white sheet while she kept her eyes closed tight. I moved to follow them, but the officer blocked my path. He told me I was detained for assault and destruction of property. I watched them wheel my daughter down the hallway while I stood there helpless. The principal kept giving her statement to anyone who would listen while they put handcuffs on me right there in the hallway.

Students were watching from their classroom doorways and some had their phones out recording everything. The officers walked me past all those staring kids and I caught one last glimpse of Laya on the gurnie with a female paramedic holding her hand and talking to her softly. At least someone was being gentle with her while they treated me like a criminal.

They put me in the back of the police car and drove me to the station while I kept asking about my daughter, but they just said to save it for the detective. At the station, they took me through the booking process with fingerprints and photos against the white wall. My hands were still bleeding and they had to clean them before they could get good prints.

When they finally gave me my phone call, I didn’t waste it on a lawyer. I called the hospital to check on Laya, but they wouldn’t tell me anything since I wasn’t there in person. All they’d say was that she was examined and I’d have to come in person for any information. I found out later that a victim advocate had met Laya at the hospital for the snee exam while I was stuck in that holding cell.

This woman stayed with her through the whole process and explained each step so Laya wouldn’t be scared. The evidence collection took hours with photographs and swabs and measurements while I sat in custody, not knowing what was happening. They released me that evening with a citation and a court date for the property damage charges.

The desk sergeant mentioned something about the principal not pressing assault charges at this time, which made it sound like she was doing me some kind of favor. I practically ran to my car in the station parking lot and drove straight to the hospital. I found Laya in a room on the third floor all cleaned up, but her eyes looked empty, and she flinched when I moved too fast toward her bed.

She whispered that I shouldn’t touch her, but please don’t leave either. I pulled the chair close to her bed so she’d know I was there, but gave her the space she needed. We sat there for a while without talking until Detective Paula Norris showed up with her notebook. She interviewed us separately, starting with me in the hallway while a nurse stayed with Laya.

I gave her the exact times from Laya’s texts and told her about the secretary refusing to leave her desk and the principal holding up five fingers for her lunch. The detective took notes without much expression, but I saw her jaw get tight when I mentioned that five finger signal. She went in to talk to Laya after that, and I could hear soft voices through the door, but not the actual words.

The hospital discharge planner came by with a stack of pamphlets about trauma responses and therapy resources and what we should expect in the coming days. She talked about safety planning and follow-up appointments and gave us numbers to call if we needed help. My brain couldn’t process all the information she was throwing at us about counseling and support groups and medical follow-ups.

She kept talking about normal reactions to abnormal situations and how recovery isn’t linear and all these terms that just went over my head. All I could think about was getting Laya home and safe and figuring out how to deal with everything that had just happened to us. The discharge nurse wheeled Laya out to my car while I pulled it around to the emergency exit.

I helped her into the passenger seat and she immediately curled up against the window. We drove in silence for 10 minutes before she finally spoke. Don’t tell Grandma yet, she said quietly. Or anyone. I can’t handle people knowing. I nodded and kept driving. The rest of the ride was silent except for her occasional sniffling. When we got home, I carried her bag inside while she walked slowly to the door.

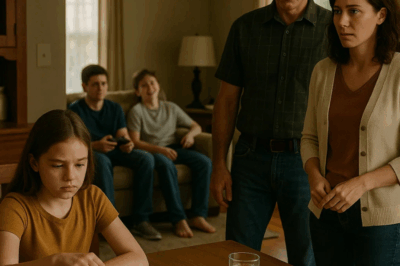

I went through every room checking windows and testing locks. The back door got an extra chair wedged under the handle. I pulled all the curtains closed even though it was still afternoon. My phone showed 14 missed calls from the school, but I deleted the contact completely. Laya stood in her doorway looking at her bed for a long moment. Then she turned and went to the living room instead.

I found her favorite blanket in the hall closet and brought it to her. She wrapped herself up on the couch and closed her eyes. Neither of us said anything about school tomorrow because we both knew she wasn’t going. My phone buzzed with a news notification and my stomach dropped. The school had released a statement about a violent incident involving a parent.

They described property damage and disruption to the learning environment. Not one word about the assault. The comments were already flooding in, calling me unhinged and dangerous. People were sharing the story and adding their own opinions about parents who can’t control themselves.

I turned my phone face down, but it kept buzzing with more alerts. Detective Norris called an hour later while Laya was dozing on the couch. She explained the interview process would be thorough but slow. She said Laya would have an advocate present for everything. Her voice was professional, but there was something understanding in her tone.

She scheduled us to come to the station in 2 days. The next morning, I made breakfast, but Laya only picked at the toast. She went back to the couch with her blanket while I answered work emails. 3 days later, we drove to the police station for her formal statement. The advocate met us in the lobby and introduced herself to Laya.

They went into an interview room together while I had to wait outside. I sat in that hard plastic chair for two hours watching the clock. Other people came and went, but I just sat there waiting. When the door finally opened, Laya looked exhausted, but the advocate said she did great. Detective Norris came out and told me Laya was very brave.

We went home, and Laya went straight back to the couch. The next afternoon, someone knocked on our door, and I found a process server standing there. He handed me papers and asked me to sign for them. It was a no trespass order from the school banning me from campus indefinitely. The document cited safety concerns and property damage.

The irony of them caring about safety now made my hands shake. I signed for it and added the papers to my growing file. My phone was going crazy with notifications, so I finally looked. Someone had posted a video of me breaking the principal’s window. It was edited to start right when I picked up the chair. You couldn’t see the principal holding up five fingers or hear anything about Laya.

The comments were brutal. Parents were calling me violent and unstable. They said people like me shouldn’t be allowed near schools. I deleted my Facebook and Twitter accounts rather than read more. That evening, my boss sent an email asking about concerning reports he’d received. He scheduled a meeting with HR for the next day.

The email mentioned conduct unbecoming and reputation damage to the company. My stomach sank, realizing this could cost me my job. I spent the night preparing documents and timeline notes. The HR meeting was uncomfortable with lots of questions about my judgment and decision-making. They put me on administrative leave pending investigation.

2 days later, I met with attorney Dmitri Lawson about the property damage charges. His office was downtown in a tall building with leather chairs. He listened to my story and took notes on a yellow pad. He said we could argue extreme circumstances, but warned me the principal had political connections. He started talking about plea deals and reduced charges.

I wasn’t ready to hear about accepting guilt for trying to save my daughter, but he said fighting it could make things worse for Yla’s case. We scheduled another meeting for next week to review options. Meanwhile, Laya had her first appointment with therapist Samra Green. I drove her there and waited in the car while she went inside. The session was mostly paperwork and safety assessment according to what Laya told me after, but Samra taught her some breathing exercises for panic attacks.

She showed Laya how to ground herself when the fear got too strong. It was the first time I’d seen Laya look slightly less scared since everything happened. She had another appointment scheduled for 3 days later. The therapy office was quiet and had soft lighting that seemed to help.

Laya said Samara was nice and didn’t push her to talk about things she wasn’t ready for. We stopped for ice cream on the way home, even though neither of us really wanted it, but it felt like something normal people would do. The house felt too quiet when we got back. I kept checking the locks, even though I’d already checked them twice.

3 days passed before a man named Cullen Burgess called from the district office. He said he was the Title 9 coordinator and needed to discuss the alleged incident at the school. The way he kept saying alleged and reported made my stomach turn. I asked what they were doing to keep Yayla safe right now. He told me everything had to follow proper process and they couldn’t rush to judgment.

I hung up harder than I meant to. The next morning, the school sent certified letters saying the three boys couldn’t contact or come near Yla. But that same afternoon, Yla’s phone buzzed with an Instagram message from a fake account. “You ruined everything,” was all it said. But we both knew who sent it.

I took screenshots of everything, including the account details and timestamp. Laya’s hands shook for the rest of the day, even after I forwarded everything to Detective Norris. She called back 2 hours later with the first good news we’d gotten. The school had security cameras in the hallway near that bathroom, and she’d gotten the footage.

You could see all three boys going into the bathroom area right when Laya’s text to me started. The timestamp showed this was happening while the principal was still at her desk eating lunch. This proved she could have helped, but chose not to. Detective Norris also got all the phone records from that day. Every single text Laya sent me was there with exact times.

My call to the school at 12:47 was logged. The secretary’s call to security about property damage came at 10:03, but she never mentioned anything about a student being attacked. Each piece of evidence made our timeline stronger. The detective said this pattern of documentation would help our case. Then the snee nurs’s report came in and I had to run to the bathroom to throw up.

The clinical words describing what happened to my daughter were worse than any nightmare. But Detective Norris said this medical evidence moved everything forward in a big way. I tried signing up to speak at the next school board meeting, but the woman on the phone said I couldn’t talk about specific student matters in public comment.

I started writing remarks about general safety protocols instead. I had to stay calm and strategic, even though I wanted to scream about what they’d done. A reporter from the local paper emailed asking if we wanted to tell our side after seeing the viral video. I wrote back saying no, but gave them Detective Norris’s contact information.

Maybe media pressure would make the district actually do something. Detective Norris called again with more news. The custodian who cleaned that bathroom area had come to her quietly. He’d seen those three boys hanging around that morning and noticed they had keys they shouldn’t have.

He was scared to say anything publicly, but agreed to give a sworn statement about what he saw. Then Dmitri called with bad news. The principal had filed for a restraining order against me, saying she feared for her safety. He said this was just a tactic to make me look dangerous before Laya’s case went anywhere.

We’d have to go to court next week to fight it. After 2 weeks, Laya wanted to try going back to the school for just one class. The counselor said this was a good step. I drove her there and walked her to the building. She made it to the hallway outside her math class. Then she smelled something and froze completely. It was the same cologne one of the boys always wore.

She couldn’t breathe and started crying. I got her out of there as fast as I could. She sobbed the whole drive home, saying she was sorry for being weak. The counselor called later and said setbacks were normal, but it felt like we were moving backward. That night, I sat at the kitchen table going through all the evidence we’d collected so far.

Phone records and timestamps and medical reports and witness statements. Each piece told part of the story of what really happened that day. The school kept saying they were investigating, but nothing seemed to change. Those boys were still walking around free while my daughter couldn’t even walk down a hallway.

The district sent another letter about their ongoing review of policies, but it was all empty words. They wanted this to go away quietly, but I wasn’t going to let that happen. Every day brought some new piece of bureaucracy or legal paperwork. Court dates for the restraining order and meetings with lawyers and forms to fill out.

All while Laya stayed home trying to heal from what they did to her. The system that was supposed to protect her had failed completely, and now we had to fight it just to get basic justice. 3 days later, Dmitri called me at work and said the DA wanted to meet about my property damage charges. I drove to his office and he explained they were offering a plea deal for misdemeanor property damage with probation and paying for the principal’s window.

He thought I should take it because fighting the charges could complicate Laya’s case and make me look unstable in court. My gut wanted to fight because I had a good reason for what I did, but Dmitri kept saying Laya needed stability more than I needed to prove a point. I signed the papers even though it felt wrong admitting guilt for trying to save my daughter.

The next morning, Cullen Burgess from the district called about interim safety measures for when Laya returned to the school. They offered schedule changes so she wouldn’t see those boys and an adult escort between classes and access to a private bathroom. I wrote down every gap in their plan, like what happens during fire drills or assemblies or if the escort was absent.

Burgess kept saying it was the best they could do while still investigating, but their best wasn’t good enough to protect her before. So why would it be enough now? 2 days later, I was loading groceries into my car at the store when someone called my name. I turned and saw a man in a suit walking toward me fast. He said he was one of the boy’s fathers and I was ruining his son’s future over teenage mistakes that got blown out of proportion.

I kept loading my groceries and didn’t respond, but he followed me around my car saying his son was losing his college scholarships and getting death threats online. He threatened to sue me for defamation if I didn’t make Laya drop the charges. I got in my car and started it, but he kept talking through my window about how boys do stupid things sometimes and we were destroying his family.

My dash cam was recording everything, including when he said his son might have gotten carried away, but didn’t mean any real harm. I drove off while he was still talking and saved that video file immediately. That afternoon, the district sent out an email to all parents calling the incident a student conflict that was addressed through proper channels.

They praised their quick response and commitment to student safety without mentioning the assault or that I had to break a window to get help. I started writing a response listing the actual timeline with every text and phone call and how long each person took to respond or not respond. I included the secretary refusing to leave her desk and the principal holding up five fingers for her lunch and the three boys having keys. they shouldn’t have had.

Dmitri reviewed my draft and made me take out the parts, calling them incompetent and negligent, even though that’s exactly what they were. Detective Norris called that evening with an update on her investigation. She’d interviewed all three boys separately over the past 2 days, and their stories were completely different.

One claimed he was never in that bathroom at all. Another said Laya invited them in, and everything was consensual. The third admitted being there, but said the other two forced him to watch, and he didn’t touch her. Their parents had hired lawyers who were now trying to coordinate their stories, but it was too late because Norris already had their first statements recorded.

She said the contradictions actually helped our case because innocent people don’t need to coordinate lies. A week later, someone knocked on our door at dinnertime. Two people from child protective services stood there with clipboards saying they needed to do a mandatory home visit because the case involved a minor.

They walked through our house checking if Laya had a safe bedroom and enough food and if I seemed stable enough to care for her. It felt humiliating having strangers judge our home, but the case worker actually gave us helpful resources for trauma counseling and victim compensation funds. They determined Laya was safe, but kept the case open to provide ongoing support services.

3 weeks into therapy with Samara, something amazing happened. Laya slept through the entire night without waking up screaming or crying. She’d been using the grounding techniques Samara taught her, like naming five things she could see and four she could hear and three she could touch. That morning, she came downstairs looking rested for the first time since the attack.

We celebrated quietly with her favorite blueberry pancakes and didn’t talk about why it was special, but we both knew this was huge. Detective Norris had been busy with subpoenas and called with big news. She got the principal’s phone records from that day, showing multiple calls coming in during her lunch break that she didn’t answer.

The records proved she was lying about not knowing there was an emergency. Her lawyer tried to argue the records were private and inadmissible, but the damage was already done because now everyone knew she chose her salad over student safety. The next Monday, Laya wanted to grab something from her locker, even though she wasn’t going to classes yet.

We went early before school started, and when she opened her locker, a piece of paper fell out. Someone had written that she was a lying who was ruining good kids’ lives. She started shaking and couldn’t breathe. I took photos of the note and marched to the office where they finally agreed to install more cameras near her locker and classroom areas.

It wasn’t enough, but it was something more than their previous nothing. The restraining order hearing came up the following week. The judge listened to both sides and ended up issuing mutual stayaway orders, criticizing both the principal’s delayed response and my property damage. She said, “We both acted inappropriately, even though the situations weren’t remotely comparable.

” Dmitri said afterward, “This was actually good because the judge didn’t label me as the sole aggressor, which would have hurt Laya’s case. The principal had to stay away from us, too, which meant she couldn’t testify as easily about my behavior that day. It wasn’t the vindication I wanted, but in this messed up system, it counted as a win.

” 3 days later, Cullen Burgess called me into an executive session at the district office where he sat with two lawyers and admitted the school hadn’t followed any of the right steps when Laya reported the boys following her home months ago. They wanted to avoid a federal complaint and offered mediation instead of fighting us in court.

Burgess kept rubbing his forehead and looking at papers showing all the times we’d asked for help and been ignored. The lawyers pushed a stack of forms across the table, offering counseling funds and policy changes if we’d sign away our right to sue. I took the papers home to think about it. But that same afternoon, Dmitri called with news that made my hands shake.

Another girl’s lawyer had contacted Detective Norris, saying those same three boys had cornered his client in an empty classroom last year, but she’d been too scared to tell anyone until she heard about Laya. The girl’s statement described the exact same pattern where they’d follow her and make comments about her body before trapping her alone.

Detective Norris said this changed everything because now we had proof they’d done this before and the school should have known. She spent the next two weeks putting together a case file thicker than a phone book with witness statements and timeline charts and security footage from both incidents. When she finally submitted it to the DA’s office, she called to warn us that prosecutors never file all the charges police recommend, but she’d fought hard for as much as possible.

The waiting was awful, but after 10 days, the DA’s office called Dmitri with their decision. They filed criminal assault charges against two of the boys and sent the youngest one’s case to juvenile court since he just turned 17. Some charges got dropped for lack of physical evidence, but the main assault charges stuck, which was more than most victims ever see.

The same week, I had to face my own legal problems when the plea offer for breaking the principal’s window came due. Dimmitri said taking the misdemeanor deal would help Laya’s case by showing I wasn’t some crazy violent person, and the judge would give me probation with community service instead of jail time. Standing in that courtroom admitting guilt for property damage while those boys hadn’t even been arraigned yet made my throat burn.

But I signed the papers and accepted 6 months probation, plus 200 hours picking up trash on highways. Meanwhile, the Title 9 investigation finally wrapped up with results that sounded good on paper, but felt hollow in reality. The boys got removed from campus temporarily and had to do online school while Laya got a tutor to help her catch up on missed work, and the principal got put on administrative leave pending further review.

The district wouldn’t admit they did anything wrong, but their actions said everything their lawyers wouldn’t let them say out loud. Two weeks before the criminal trial started, Laya had to testify at a closed preliminary hearing to determine if there was enough evidence to proceed. Her advocate held her hand the whole time while she answered questions about that day in the bathroom, and I could see her shaking from across the courtroom.

The defense lawyer tried to confuse her with questions about exact times and why she didn’t scream louder, but she got through it without breaking down completely. Afterward, in the hallway, she looked exhausted, but said facing them made her feel stronger, even though every word had been terrifying. That weekend, a reporter from the local paper published a huge investigation about how schools handle assault cases using our story without names as the main example.

The article had charts showing how many reports get were ignored and quotes from experts saying schools care more about liability than student safety. Within hours, the school board announced emergency meetings to review all their policies and parents started showing up at board meetings demanding real changes.

My boss called me in the next Monday saying HR had reviewed everything and decided on a two-week unpaid suspension for missing work during the incident and creating negative publicity for the company. They made me sign a performance improvement plan with monthly check-ins, and everyone at work looked at me differently now, but at least I kept my health insurance for Laya’s therapy bills.

The suspension actually gave me time to drive Laya to her new therapy support group for teen assault survivors that Samra had recommended. I waited in the parking lot reading emails on my phone while she went inside to a room with five other girls who understood what she’d been through without needing explanations. After an hour, she came out with red eyes, but something different in her posture like she’d put down a heavy weight.

She didn’t talk about what happened in there, but on the drive home, she said one sentence that made everything else worth it. I survived. The other girls had nodded when she said it, and for the first time since this started, she’d felt less alone in what happened to her. The district’s lawyers called me 3 days later with their mediation offer, and I could tell from their careful tone they wanted this to go away quietly.

They wouldn’t say the school did anything wrong, but they’d cover all of Laya’s therapy costs, plus bring in outside experts to review their emergency response protocols and require every staff member to complete 40 hours of training on handling student safety situations. I wanted them to admit what they did to us, but Dimmitri reminded me that getting Laya’s treatment paid for mattered more than my need for them to say sorry out loud.

So, I signed their papers with hands that shook from holding back everything I wanted to scream at them. The next week, we sat in a small office with a new counselor who specialized in helping kids return to the school after trauma. And she spread out papers showing different options while Laya gripped my hand under the table.

She suggested starting with just two morning classes, math and English with a quiet room available if Laya needed to leave, and an adult escort to walk her between buildings so she’d never be alone in the hallways. Yayla’s voice was barely above a whisper when she said she wanted to try, even though I could see her whole body tense at the thought of walking through those doors again.

We practiced the route she’d take the weekend before school started, walking the empty hallways while she pointed out safe spots she could go if she felt scared. The counselor’s office on the second floor, the nurses station near the front entrance, the library with its back exit she could use if she needed to leave fast. Monday morning came too quickly and Laya put on her new backpack with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking, but she got in the car anyway, and I drove slower than usual, trying to give her more time to prepare.

The escort met us at the side entrance, a kind older woman who’d been briefed on everything, and she walked Laya to her first class while I sat in the parking lot for 2 hours in case she needed me. She made it through both classes without calling me, though, the counselor texted that she’d used the quiet room twice to do her breathing exercises when the hallways got too loud between periods.

When I picked her up at 11:30, she looked exhausted. Dark circles under her eyes and her shoulders hunched forward. But there was something else there, too. A tiny spark of pride that she’d done it. We went straight to the ice cream shop, even though it was barely noon. And she got three scoops of different flavors.

While I got my usual vanilla, and we sat outside eating slowly while she told me about how her English teacher had welcomed her back without making a big deal about where she’d been. 3 weeks into this new routine, I got an email from the district announcing personnel changes. And buried in the middle was one line about the principal being reassigned to a curriculum development position at the district office starting immediately.

The teachers union had protected her from being fired completely, but at least she wouldn’t be around kids anymore, stuck in some windowless office reviewing textbooks instead of ignoring students in crisis. Dmitri called that same afternoon with news about the boy’s cases moving forward, and said the youngest one’s lawyer wanted to meet about a possible plea deal that would include court-ordered treatment and permanent restraining orders that would follow him even after he turned 18.

The other two were still fighting the charges. Their expensive lawyers filing motion after motion trying to get evidence thrown out. But the one taking the deal would have to allocate what happened as part of his plea, which would make the other cases stronger. Laya listened when I told her about it after dinner, and nodded slowly before saying she felt a little safer, knowing at least one of them admitted what they did, even if it was just to get a lighter sentence.

Saturday morning, we went to the garden center and Laya picked out a small oak tree, running her fingers over its thin trunk, while I loaded bags of soil and mulch into the cart. We dug the hole together in the backyard’s corner where it would get morning sun. Neither of us talking about what it meant or represented, just focusing on making sure the hole was deep enough and the roots had room to spread.

Every morning after that, Laya would go outside before school to water it, standing there with the hose for exactly 5 minutes like it was the most important task in the world. And I’d watch from the kitchen window as she tended to this one small thing she could control. Three months crawled by with therapy twice a week and school three mornings a week and court dates that kept getting postponed.

And then one Tuesday evening while we were making spaghetti together, I made a stupid joke about the pasta looking like worms. And Laya actually laughed. Not just a polite smile, but a real laugh that came from her stomach. It only lasted a second before she caught herself and went quiet again.

But for that one moment, she sounded like herself, like the girl who used to sing in the shower and leave her shoes everywhere and argue with me about curfew. Now I’m sitting at our kitchen table typing this while Laya does her geometry homework across from me, occasionally asking for help with a problem, even though I know she can solve them herself.

She’s back at the school part-time with support systems in place, sleeping through most nights without nightmares, and the boy’s cases inch through the legal system. But we don’t check for updates every day anymore. We’re not over what happened because you don’t just get over something like that. But we’re living with it, taking things one day at a time. And right now, that’s enough.

Thanks for hanging out with me today. Seriously, life’s always throwing lessons at us if we actually stop and pay attention. Until we cross paths again, my friend. If you made it to the end, drop a comment. I love reading all your comments.

News

CH1 What Kind of Gun Is That? — Japanese Navy Horrified by the Iowa’s 16-Inch Shell RANGE

Philippine Sea. October 1944. A Japanese naval officer raises his binoculars, his hands trembling. On the horizon, four massive shapes….

CH1 Germans Couldn’t Understand How American VT Fuzes Destroyed 82% Of Their V-1s In One Day

For 80 terrifying days, London was on the brink of collapse under the V-1 buzz bomb attacks. What the public…

What’s the hardest part about being born on a leap year?

My parents told everyone I died at birth, but I’ve been living in our soundproof basement for 16 years. They…

How did your father treat women?

How did your father treat women? My father made all the women in our house ask permission for every action…

How did a school prank send everyone straight to the ER?

How did a school prank send everyone straight to the ER? The whole thing started because Jay wanted to be…

At the restaurant, the waiter wrote on my receipt: “Don’t go home tonight. Trust me.”

At the restaurant, the waiter wrote on my receipt, “Don’t go home tonight. Trust me.” The ink was still wet…

End of content

No more pages to load