My teacher refused to lock down during a real school shooting. Even blocked the light switch while gunshots got closer. When I begged her to let us hide, she said, “Sit down or you’re expelled.” I just stared at her. That was one year ago. Last week, she was led out of her apartment in handcuffs.

I was in Miss Brown’s AP History class when the lockdown announcement crackled over the PA. Lockdown. Lockdown. This is not a drill. We’d done this drill a hundred times since kindergarten. Lights off. Hide in the corner. Stay quiet. Simple.

Everyone started moving automatically, but Miss Brown stepped in front of us with that look she gets when someone questions her authority. Get back to your desks now. Her voice had that edge that meant business. I didn’t approve any lockdown drill today. I raised my hand out of habit, but Miss Brown, we’re supposed to. The only procedures you follow are mine.

Sit down or you’re all getting zeros on your presentations. Then she launched into her whole I’ve been teaching for 25 years speech. The one about respect and how her generation didn’t need constant handholding. Here’s the thing about Ms. Brown.

She was one of those teachers who was super strict about weird stuff, but lazy about actual teaching. She’d mark you absent for being 30 seconds late, but give everyone A’s on essays she obviously hadn’t read. I once turned in a paper with a whole paragraph about Spongebob in the middle just to test it. Got a 98, so most of us sat back down.

Nobody wanted to risk their GPA over what was probably just another drill. But then the announcement repeated. Code red. This is a code red. All staff and students follow lockdown procedures immediately. That never happens in drills. They announce it once and that’s it. My stomach started doing this weird flip thing.

The same feeling I get before a big test I didn’t study for, except worse. I kept glancing at the door. The hallway was still bright, fluorescent lights blazing. In drills, teachers always turn off their lights immediately. Then I heard it pop like firecrackers, but not. Everyone’s phone started buzzing at once. I pulled mine out under my desk.

My boyfriend Tyler was in chemistry two halls over. His text made my blood freeze. Hiding in supply closet. Someone has a gum. Where are you? More texts flooding in behind filing cabinet in main office. Under Mr. Garcia’s desk, I showed Miss Brown my phone. My boyfriend says there’s someone with a I see what’s happening here.

You think you can stage some elaborate prank to get me in trouble? Get me fired? The popping sounds were getting louder. Closer. Someone screamed in the hallway. Not a fun scream, not a playing around scream. That’s probably drama class practicing, Ms. Brown said, but even she didn’t sound sure anymore.

I could see Mr. Peterson’s class across the hall. Lights off. No movement. Just darkness where 20 kids should have been. My hands were shaking so bad I could barely type. Henderson won’t let us hide. Still at desks. Tyler, what? Get to safety now. Ben tried next. Sweet Ben, who never argued with anyone. Ms. Brown, please.

This feels real. Feelings aren’t facts. Ben, sit down. More running in the hallway. Lots of feet all going the same direction. away from something or someone. The PA crackled again but cut off midward. That’s when we heard the shots. Not pops anymore. Bang! Bang! Bang! Like someone slamming a metal door, but sharper, louder, real. I stood up. “We need to hide now. Sit down or you’re expelled.” Ms. Brown moved to block the light switch.

“I will not lose my job because you children want to play games.” Something in me snapped. “I don’t care.” I sprinted for the lights. That’s when everyone lost it. Half the class rushed to the safe corner. The other half froze at their desks, torn between a lifetime of following rules and that primal voice screaming, “Danger.” Ms. Brown grabbed at my arm as I passed, but I yanked away. She was yelling about disrespect and consequences.

“You’re all being hysterical. This paranoia is exactly what social media has done to you. Manufactured fear, but we weren’t listening anymore. Desks scraped across Lenolium as we barricaded the door. Someone was crying. Someone else was praying. The kids who’d frozen finally scrambled over, cramming into our corner. 23 teenagers trying to become invisible. Everyone except Ms. Brown. She stood at her desk, arms crossed, fury radiating off her.

The doororknob rattled. Everyone stopped breathing. The handle turned, locked. Thank god. Locked. A shadow passed under the door. Paused. We could hear breathing on the other side. Or maybe that was just my heart pounding in my ears. Footsteps moving on. Those were the longest 10 seconds of my life.

The SWAT team found us 40 minutes later. Ms. Brown was still babbling about how we’d overreacted to a simple drill. And a week later, we finally found out why. Because that’s when they told us who the shooter was. Jake Wilson from my sophomore English class.

The quiet kid who sat in the back corner drawing anime characters in his notebook. The paramedic wrapped the blood pressure cuff around my arm while I sat on the gurnie outside. My whole body shaking like I had hypothermia even though it was May. She kept checking my pulse and asking if I could breathe okay, but all I could think about was Jake walking past our door.

Jake with a gun. Jake, who I’d lent a pencil to last week, Detective Santos showed up with her badge and notebook. Crouching down to my eye level while asking me to walk through everything that happened in Ms. Brown’s room. I told her about the announcement, about Ms.

Brown making us stay at our desks, about the sounds getting closer. She wrote everything down, nodding when I mentioned turning off the lights myself. The parking lot was chaos with parents running everywhere, news vans setting up, ambulances leaving with their sirens on.

Mom crashed through the police tape, still wearing her hospital scrubs, mascara running down her face as she grabbed me so hard I couldn’t breathe. She kept touching my face, my arms, checking for injuries that weren’t there, while demanding answers from Detective Santos about how a teacher could keep kids exposed during an active shooter. Tyler’s mom was there, too, crying and hugging him over and over while he stood there looking blank.

Detective Santos brought me to a quieter spot and pulled out her tablet, showing me screenshots of my text to Tyler about Ms. Brown not letting us hide. She said 23 students had already given the same story, that Miss Brown kept insisting it was fake, even after the gunshots started. Two kids died in the math hallway, she told me. Three more were at the hospital, all from rooms that followed protocol immediately, except for one girl who got grazed by a bullet that went through a door. Dad showed up and took over from mom, leading me to his truck without saying anything.

The radio stayed off the whole drive home, and we both jumped when a motorcycle roared past us at a red light. Our house felt wrong, too normal with its regular smell of coffee and laundry detergent.

Dad made spaghetti, but I just pushed it around my plate while my phone kept buzzing with messages from everyone asking why Miss Brown didn’t let us hide. That night, I couldn’t sleep. Just kept replaying those 40 minutes over and over. The next morning, an automated call from the district said school was canceled indefinitely and counselors would be available at the community center.

Mom called in sick to stay home with me, but I locked my bedroom door and sat on my bed thinking about how we almost didn’t barricade, how we almost stayed at our desks like Ms. Brown wanted. Channel 8 had our school on every commercial break. And then Ms.

Brown’s face filled the screen, standing in her driveway, telling the reporter she maintained control during chaos and her students were alive because she didn’t panic. Mom grabbed the remote and threw it so hard it cracked the TV screen. Tyler sent me a link to someone’s cell phone video from Mr. Peterson’s dark classroom, showing everyone hidden and silent while Ms. Brown’s voice carried through the walls talking about manufactured fear. The time stamp showed 2:47 p.m. right when she was blocking the light switch.

The video had 50,000 views in 2 hours, and the comments were brutal. I spent the next day in my room jumping every time the house creaked or a car door slammed outside. Mom brought soup I didn’t touch, and the group chat kept going off about lawyers and lawsuits, but I couldn’t focus on any of it.

Principal Foster called that evening with his careful principal voice saying the district needed my written statement about Ms. Brown’s actions separate from the police investigation.

Mom grabbed the phone and told him I’d provide it through our attorney, which was news to me since I didn’t know we were getting one. The next morning, Ben’s mom drove him over because he needed to talk to someone who was there, someone who understood. We sat on my front porch and he kept starting sentences he couldn’t finish about almost staying in his seat about what would have happened if I hadn’t turned off those lights. His hands were shaking just like mine were.

Tyler’s parents dropped him off later that afternoon and we went straight to the backyard where the picnic table sat under the big oak tree. He rolled up his jeans and showed me the dark purple bruises covering both his knees from when he’d wedged himself behind the chemical storage shelves in that supply closet. His voice stayed flat when he told me how the shots kept getting closer, and he knew I was two halls away, but couldn’t do anything about it.

We sat there for an hour, not really talking about it, but not talking about anything else either, while his fingers picked at the splintered wood on the table. Day five started with mom on the phone scheduling appointments.

And by noon, she’d found Rebecca Thompson, this lawyer who specialized in school safety cases. Her office downtown had newspaper clippings covering every wall, headlines about negligence lawsuits, and safety violations at schools across the state. Rebecca looked at mom’s notes and said, “What Ms. Brown did went beyond poor judgment.

That keeping students exposed during an active shooter situation was criminal endangerment. There’s something unsettling about how Ms. Brown keeps insisting this is all fake, even with those gunshots echoing through the halls. What makes a teacher so convinced that actual danger isn’t real when every other classroom is already dark and hidden?” She explained how other families were already filing civil suits, but criminal charges would be up to the district attorney’s office.

The community meeting on day six turned into chaos. The second Ms. Brown walked through the civic center doors with her union representative. parents started screaming immediately while she just stood there with that same controlled expression she’d had during the shooting, repeating that she’d followed her professional judgment.

Someone threw a water bottle that hit the wall behind her, and security guards had to form a circle around her to get her back outside. The detective called that same night with a question that made my whole body go cold, asking if Ms. Brown had ever mentioned Jake Wilson in class since he’d been her student 3 years ago.

Jake Wilson was the name everyone knew through whispers and group texts, but the news wouldn’t say yet. Day seven, morning. I finally made myself shower and change out of the clothes I’d been wearing for days. Dad stood at the stove making pancakes like any other Sunday, but we both jumped when the doorbell rang.

just the delivery guy dropping off a package. But that split second of panic was becoming our new normal. That evening, the news finally confirmed what everyone already knew, showing Jake’s yearbook photo from when he graduated. This quiet kid I vaguely remembered from my freshman year.

The anchor dropped the real bomb, though, saying Wilson had filed a formal complaint against teacher Patricia Brown 3 years ago for psychological abuse. Mom grabbed her phone immediately to call our lawyer while dad hunted through online records for any trace of Jake’s complaint. We found a schoolboard meeting transcript from 2021 mentioning a sealed student complaint against staff with dates that matched up perfectly, even though Miss Brown’s name wasn’t listed. Day eight.

Tyler picked me up and we drove to the empty mall parking lot where we just sat with the engine off. His hands gripped the steering wheel until his knuckles went white and he finally said she knew. She had to know it might be him and she still kept us all exposed. Ben started texting our class group chat with information his parents had found.

Three other students from Jake’s graduating class who remembered Ms. Brown having it out for him. This girl Melissa said Miss Brown had failed Jake on a technicality that almost cost him graduation and the stories painted a clear pattern of targeting certain students.

Day nine, the detective showed up at our house with a court order for Ms. Brown’s personnel file clutched in her hand. She told mom they’d found something. That Jake wasn’t the only complaint against Ms. Brown over her career. There were six others, all sealed and somehow resolved without any action taken. She needed my detailed statement about Ms.

Brown’s exact words during the lockdown. Every single thing she’d said while we begged her to let us hide. I sat at my kitchen table with the detective’s blank statement form in front of me, my pen hovering over the paper while mom made coffee in the background.

The first line asked for a description of events, and I wrote three words before crossing them out. Started again. Cross that out, too. How do you put into words the way someone’s voice changes when they’ve been in charge for so long they can’t imagine being wrong? The detective waited patiently while I tried six different ways to explain how Ms. ground stood there blocking the light switch while we heard those shots getting closer. I finally just wrote exactly what she said and did step by step.

No opinions, just facts. Day 10. My phone buzzed with a news alert while I was eating breakfast. The school board had placed Ms. Brown on administrative leave pending investigation, which sounded good until I read the teachers union statement underneath calling it a rush to judgement against a dedicated educator with 25 years of service.

The comment section was already at 300 posts, half calling her a hero for maintaining order, half calling for her arrest. Mom shot my laptop and told me to stop reading, but I’d already seen my name mentioned 14 times. That afternoon, Principal Foster showed up at our door looking like he hadn’t slept in days. He sat on our couch and stared at his hands while telling mom about the complaints over the years.

Parents saying Miss Brown was too rigid, too harsh, but she had tenure and her students got good test scores, so nothing ever happened. His voice cracked when he mentioned the two kids who didn’t ma

ke it out. Day 11 started with my phone exploding at 6:00 a.m. because someone had leaked Jake’s manifesto to a news site before the FBI could lock it down. Three whole pages about Ms. Brown. How she failed him on his senior thesis over a missing footnote. How that one grade kept him out of his dream college, how she laughed when he asked for a chance to fix it. The details made my skin crawl. dates and times and conversations he’d recorded secretly, building his case for why she deserved what was coming.

Our lawyer, Rebecca, called an emergency meeting that night with all 23 families from Ms. Brown’s classroom crammed into a conference room at the Holiday Inn. She stood at the front with a stack of papers and dropped the bomb that the school district knew about Jake’s fixation on Ms. Brown because his therapist had sent a warning 2 months before the shooting. The room erupted with parents shouting and crying and demanding answers while Rebecca tried to explain about mandatory reporting laws and liability. Day 12.

I woke up to 47 Instagram notifications because Ms. Brown had gone on some podcast called Truth in Education and spent an hour painting herself as the victim of woke culture and teenage hysteria.

She actually used my full name, called me a troubled student with attendance issues, twisted my grandmother’s funeral into me skipping class for fun. The host kept agreeing with her, saying, “Kids today are soft, can’t handle structure, need safe spaces instead of real education.” Rebecca filed a cease and desist within 2 hours, but the episode had already been downloaded 12,000 times.

My Instagram filled with strangers calling me a liar, an attention seeker, a crisis actor. Someone found mom’s work number at the hospital and started calling the nurses station, asking if she was proud of raising a daughter who destroys teachers lives. It’s day 13.

Tyler came over with his sleeping bag and sat up on my bedroom floor because neither of us could handle being alone anymore. We lay there in the dark at 3:00 a.m. both wide awake, staring at nothing. He kept going over that day how he could have pulled the fire alarm from the chemistry room. How that would have evacuated everyone before Jake even started.

The whatifs were eating us both alive, but there was nothing to say that would make it better. M. Brown’s husband, who sold real estate all over town, started a GoFundMe for her legal defense the next morning that hit $30,000 in 6 hours. The description called this a witch hunt against a dedicated teacher.

included photos of her at graduations with former students who became doctors and lawyers, carefully leaving out anyone who didn’t fit the narrative. People from three states away were donating and leaving comments about how liberals are destroying education. Day 14, Ben’s mom called to say they were pulling out of the group legal action. Her voice shaking as she explained that Ben’s dad’s construction company had just lost three major contracts with no explanation.

She kept saying they couldn’t prove it was connected, but everyone knew Ms. Brown’s brother-in-law ran the biggest development firm in town and golf with half the city council. Daniel Harris from my grade found me at the coffee shop that afternoon, his phone already out and shaking in his hand as he slid into the seat across from me.

He’d been hiding in the main office during everything, pressed behind the secretary’s desk where he could see the security monitor, and he’d recorded the whole thing on his phone without even thinking about it. The video was grainy, but clear enough to see Ms. Brown walking down the hallway 30 seconds after the first shots, not running, not ducking, just walking like it was any other day between classes, while Mr. Peterson’s door was already barricaded, and Mrs.

Garcia had her kids hiding under desks. Daniel forwarded it to Detective Santos right there in front of me, his fingers moving so fast they kept missing buttons. Day 15, I went back to therapy for the first time since middle school when my parents got divorced. Dr.

Patel’s office had the same fake plants and beige walls and that white noise machine that was supposed to be calming but just made me think of static. I told her about the shadow under the door and how I still hear Miss Brown saying we’re being hysterical while people were dying down the hall.

She wrote notes on her yellow pad and asked me to describe what I felt in my body when I remembered it. Daniel’s video hit Twitter before dinner that same day and by midnight # brownnew was trending with 40,000 retweets. People kept slowing it down and zooming in where you could see her checking her phone while other teachers were dragging kids into classrooms.

The time stamp clear as day showing this was after the shooting started. News vans showed up at Daniel’s house and his parents had to take him to stay with his aunt in Boston. Day 16. Detective Santos called me in to look at the footage with some specialist from the state who kept pointing at the screen with her pen.

She showed me how there was no startle response when the shots went off. No surprise on Ms. Brown’s face, just this calm decision to keep walking. They were building a case for willful endangerment, she said, which could mean up to 5 years in prison.

Mom picked me up from the station and drove straight to the district office where she filled out the paperwork to pull me out for homeschooling. Miss Brown walking calmly down the hall while other teachers barricaded doors is the kind of detail that makes lawyers rub their hands together and insurance companies reach for their checkbooks.

She took three weeks of vacation time she’d been saving for years and told me she didn’t care about my college applications. She cared about me being alive. And we both ended up crying in the kitchen while the pasta boiled over on the stove. Day 17. Ms.

Brown’s lawyer held this big press conference on the courthouse steps with three of her former students standing behind him in suits. One was a state senator now who kept talking about rushing to judgment and promised to investigate the investigation. While the lawyer claimed the video was doctorred and demanded independent analysis. Tyler’s parents didn’t wait for any of that and transferred him to St. Mary’s private school the same day. His mom explaining they couldn’t wait for the system to sort this out.

He texted me constantly from his new school, feeling guilty about leaving, even though I kept telling him to go, to get out while he could. Our phones became this lifeline, both of us waking up at 3:00 a.m. and texting each other just to make sure the other was still there. Day 18. I couldn’t sleep again, so I started googling Ms. Brown and found this old Reddit thread from 2019 where someone asked, “Who is your worst teacher?” Three different accounts mentioned her by name, talking about her mind games and how she’d pick one student each year to torment. The thread had been deleted, but the cached version was still there on the Wayback Machine. So, I screenshot everything and sent it to our lawyer.

Day 19. The schoolboard meeting turned into complete chaos when parents started screaming at each other across the auditorium. Half of them wanted Ms. Brown arrested immediately and the other half thought she was being scapegoed with one woman yelling that Ms. Brown saved those kids by maintaining order.

Then’s dad stood up even though they pulled out of the lawsuit and shouted back that she nearly got them all killed and security had to clear the whole room while people were still pushing and shoving in the parking lot.

Rebecca Harris, Daniel’s mom, filed for a restraining order the next morning after Ms. Brown’s supporters started showing up at our houses, taking photos of our front doors and posting them online with our addresses. The judge said without direct threats, it was just free speech, though, and Rebecca sat in the courtroom crying while the judge explained that taking pictures from public property wasn’t illegal. That same

night, I couldn’t sleep and kept scrolling through my phone, looking at all the comments defending Ms. Brown. Around 3:00 a.m., something inside me just snapped. I grabbed my laptop and started pulling up the audio recordings from that day that the news had released. The timeline was public record now, thanks to the investigation, I synced up Ms. Brown’s exact words with the sounds of gunshots in the background.

Setting up my phone against my desk lamp, I hit record and just started reading from the transcript. I didn’t approve any lockdown drill today. Bang. Echoed from my laptop speakers. Sit down or you’re all getting zeros. Bang. bang. My hands were shaking, but I kept going through every single thing she said while kids were dying down the hall.

When I posted it to Tik Tok at 4:17 a.m., I didn’t expect anything. By noon, it had 2 million views and climbing fast. Other kids from school started making their own videos showing what their teachers did. Mrs. Garcia from Spanish had everyone under desks in 8 seconds. Mr. Peterson had his whole class in the storage closet before the second announcement. Coach Williams literally carried two freshmen who froze into the equipment room.

Every single teacher except Ms. Brown had their students hidden within 30 seconds. The hashtags exploded across every platform. Teachers save students showed heroes while # brown chose control showed our classroom still sitting at desks while gunshots echoed. That night around 2 a.m. Tyler showed up at my house without warning.

His mom had found him having a panic attack in his bathroom and drove him over. We sat in my driveway until the sun came up sharing earbuds and listening to old playlists from before everything changed. He kept whispering the same thing over and over like a prayer. The district attorney’s office called a press conference the next morning.

23 counts of reckless endangerment of a minor, one for each student in our class. Ms. Brown turned herself in wearing a navy suit with all her teaching awards pinned to her jacket like medals. The cameras caught every second as she walked up those courthouse steps with her chin high and this little smile on her face.

Her bail hearing happened that afternoon and the judge set it at $50,000. Her supporters had a GoFundMe running before she even got processed. 2 hours and 17 minutes was all it took to raise the full amount. She walked out of that courthouse still smiling and stopped right in front of the cameras. Mom had to grab both my arms and physically drag me back to the car when Ms. Brown started talking about vindication and control.

The victim’s family started meeting at the community center on Wednesdays, but I couldn’t make myself go. Mom went instead and came back with huffy eyes every single time. She’d just hold me extra tight and not say anything about what she heard there. Ben texted me a photo of something his mom found while cleaning out old PTA files from her garage.

Jake Wilson’s junior year essay with Ms. Brown’s comments all over it in red pen. The essay looked fine to me, but her notes were brutal about lazy thinking and disappointing effort. At the bottom, in her perfect handwriting, she’d written a note about discussing his future in her course. Detective Santos called me the next day saying they’d found six more complaints against Ms. Brown going back 15 years.

All from male students and all mentioning something the parents called psychological manipulation. Every single complaint got dropped after closed door meetings with administration. The detective sounded tired when she told me this wasn’t unusual in cases like this. Principal Foster resigned at an emergency press conference that nobody expected. He stood at that podium and actually admitted he failed us. He said Ms. Brown should have been removed years ago, but he chose the easy path instead.

The reporter seemed shocked that someone was actually taking responsibility for once. 2 days later, Ms. Brown’s lawyer filed a counter suit against the school district for $5 million. They claimed the district was scapegoating her for their own security failures.

My phone buzzed with the news alert while I was in my therapist’s waiting room, and I actually laughed out loud at the audacity. The next day, Rebecca called a meeting at the community center, and all 23 families showed up. She stood at the front with stacks of papers and started handing them out while explaining we weren’t just defending ourselves anymore.

We were filing criminal complaints with the state board and launching a federal civil rights lawsuit. Parents were signing papers and exchanging phone numbers while Rebecca’s assistant took notes on her laptop. That night, I couldn’t sleep, so I started writing everything down in this old notebook I found in my desk drawer. Every word M.

Brown said during those 47 minutes went on the page. The way she blocked the light switch, how she threatened us with zeros and expulsion while gunshots got closer. Dr. Patel said, “Writing helps process trauma, but it felt more like building a case.” 3 days later, my phone started blowing up with notifications about this new website. A group of Ms. Brown’s former students had created something called Survivors of Room 203.

I clicked the link and saw testimonial after testimonial pouring in. 37 stories in the first few days alone. Kids from 10 years ago describing the same tactics. Public humiliation when you questioned her. Grades mysteriously dropping if you challenged her authority. Mind games that made you doubt yourself. The pattern was right there for everyone to see. A local reporter reached out through my mom asking if I’d do an interview.

My hands were shaking when the camera started rolling, but I kept my voice steady and told them exactly what happened, how she looked at us while gunshots echoed in the hallway and chose her authority over our lives. The segment aired that evening and my phone didn’t stop buzzing for hours.

Ben surprised everyone the next day by posting his own story on Instagram despite his parents begging him not to. He wrote about almost staying seated because he was more afraid of Miss Brown’s punishment than dying. He said, “I saved his life by defying her.” Within 3 hours, his post had 10,000 shares and climbing. The FBI agent called my parents that afternoon with new information they’d uncovered. Jake had texted a friend the night before the shooting about Ms.

Brown destroying him in front of everyone. The friend had deleted the messages out of guilt, but investigators recovered them from the phone company’s servers. The texts were explicit about Jake’s plans and his specific hatred for Ms. Brown. 2 days later, news broke that Ms.

Brown’s husband had filed for divorce and moved out in the middle of the night. Court documents showed he’d been planning it for months, but the shooting pushed up his timeline. Even her own husband was abandoning ship. I had to go back to school to get my stuff since the semester was ending. Room 203 was still sealed with crime scene tape across the door.

The hallway felt wrong and smelled like industrial cleaner trying to cover something else. I grabbed my things from my locker as fast as I could while Tyler waited in the parking lot with a car running. The prosecution brought in this expert named Dr. Katherine Mills who specialized in crisis response.

She spent 3 days reviewing everything and her conclusion was brutal. Ms. Brown violated every single established protocol and showed gross negligence that directly endangered our lives. Ms. Brown’s supporters raising $50,000 in just 2 hours makes me wonder who exactly has that kind of money and motivation to defend a teacher who kept kids seated during gunshots. Her report was 50 pages of professional language basically saying Ms.

Brown chose control over children. Then Miss Brown’s supporters decided to organize a rally at the courthouse which turned into a disaster. Parents of the two students who died showed up as counterprotesters. When someone yelled that Brown did nothing wrong, one of the mothers just collapsed, sobbing on the courthouse steps.

The photo went viral within minutes, showing our town completely divided. News vans from three states away started showing up. Tyler’s mom organized a support group meeting at the community center that weekend where 23 of us survivors gathered in a circle of folding chairs. The girl from Mr.

Peterson’s class kept twisting her hair around her finger while she talked about how their teacher immediately flipped desks to make a barrier. Another kid from the science wing described his teacher pulling them into the chemical storage room and blocking the door with a filing cabinet. Everyone had the same story except us. Their teachers protected them.

Ours tried to get us killed. One girl just looked at me and said, “We shouldn’t have had to save ourselves,” and everyone nodded. The state board of education finally launched their investigation on day 35 after the media pressure got too intense. Rebecca called me that afternoon to say they were subpoenaing 10 years of records from the school district.

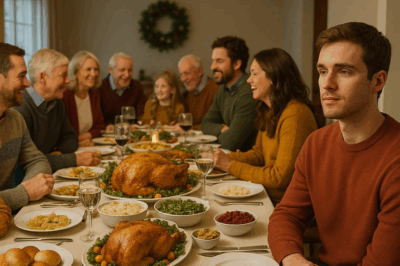

She said the investigators found 17 formal complaints against Mrs. Brown that were never properly documented. Criminal charges against the administrators who covered for her were now on the table. Mom arranged dinner with Tyler’s family that night where we all sat around their dining room table pushing food around our plates.

Tyler’s dad kept trying to talk about his college plans for next year, but the words just hung there. His mom mentioned summer vacation ideas, but stopped mid-sentence when a car backfired outside and we all jumped. We were all pretending we weren’t different now. that loud noises didn’t make us freeze, that shadows didn’t make our hearts race.

On day 40, I found myself at the state capital building with a microphone in front of me and 300 people in the audience. The legislative committee sat behind their long desk taking notes while I read from my prepared statement. I told them Miss Ms. Brown weaponized her authority while a weapon was in our school. I said she chose her ego over our lives. I asked how many complaints it takes before someone acts.

The representatives just stared at me when I finished. 2 days later, a custodian named Frank contacted our lawyer with something huge. He had security footage from 3 years ago that nobody knew existed because it was from an old camera system they forgot to disconnect. The video showed Jake leaving Ms. Brown’s classroom with tears streaming down his face before punching a wall so hard his knuckles bled.

The time stamp matched exactly with the day Jake filed his complaint against her. The original investigation never included this footage because nobody thought to check the old system. Ben’s family called us on day 42 to say they were rejoining the lawsuit. His dad’s company mysteriously got all those contracts back the same day the FBI started investigating Ms.

Brown’s brother-in-law for witness tampering. His dad said some things are more important than money. But we all knew the truth. The brother-in-law backed down when federal agents showed up at his office. The grand jury met the next week and upgraded Ms. Brown’s charges to attempted murder through depraved indifference.

Her lawyer went on the news calling it prosecutorial overreach, but the DA held a press conference explaining that keeping children exposed during an active shooter situation showed extreme disregard for human life. The legal experts on TV said this charge usually only applies to drunk driving deaths, but this case might set a new precedent.

Tyler got his early admission letter to State University on day 45, but called them that afternoon to defer for a gap year. He came over that night and we sat on my porch while he explained he couldn’t leave me to face the trial alone. We both knew what we had wasn’t normal teenage stuff anymore. We were connected by something darker now, something that went beyond love into shared survival. Day 47 was my first good day since the shooting. I went six whole hours without thinking about it while helping mom reorganize the garage. Then the guilt hit me like a truck.

How could I forget even for a minute when two kids were dead? Dr. Patel said healing isn’t linear during our session, but it felt like betrayal. It felt like I was abandoning the kids who didn’t make it out. The state board held their hearing on day 50 to revoke Miss Brown’s teaching license.

She showed up in a black suit, claiming this was a lynching of a dedicated educator. When they showed her testimonials from 37 former students describing her behavior, she called them weak children who couldn’t handle high standards. Several board members visibly pulled back from their microphones.

The woman running the hearing had to call for order twice when Ms. Brown started yelling about cancel culture. They voted unanimously to revoke her license permanently and referred the case to the attorney general for additional charges related to child endangerment spanning her entire career. The next few weeks passed in a blur of legal meetings and therapy sessions until Detective Santos called me on day 52 with news that made my hands shake so bad I dropped my phone.

She’d been digging through old personnel files at the district office when she found a sealed folder from 2009 about Ms. Brown’s transfer from Westfield High. A student there had tried to kill herself and left a three-page note naming Ms.

Brown specifically for the daily humiliation and mind games that pushed her to that point. The school quietly moved Miss Brown to our district rather than investigate because the superintendent’s wife was Ms. Brown’s cousin. Within hours of Detective Santos leaking this to a reporter friend, my phone started blowing up with notifications from a Facebook group called Survivors of Patricia Brown that already had 200 members.

Former students from three different schools were sharing stories going back 25 years about her tactics, the public shaming, the way she’d give contradictory instructions, then punish kids for being confused, how she’d gaslight students about things she’d said minutes earlier.

One girl from 1998 wrote that Miss Brown told her she was too stupid for college in front of the whole class, then denied it when her parents complained. Another kid from 2003 said Ms. Brown made him stand in front of the class while she listed everything wrong with his essay, including mocking his stutter.

The pattern was always the same, always protected by administrators who found it easier to transfer her than deal with complaints. Two days later, my mom drove me to meet the Johnson’s and the Garcas, whose kids, Michael and Sophia, died in the shooting because they stayed at their desks following Ms. Brown’s orders. Mrs. Johnson, held my hand while tears rolled down her face and said she didn’t blame any of us survivors. Mr.

Garcia’s voice cracked when he told me, “We fought to save ourselves while their children never got the chance because they followed the rules.” We sat in their living room crying together for an hour, looking at photos of Michael and Sophia at prom just 3 weeks before they died.

Rebecca called that afternoon with updates on the prosecution strategy and what she told me made me run to the bathroom to throw up. They had evidence Ms. Brown knew Jake was likely targeting her based on previous incidents where he’d confronted her after class, but she deliberately kept us exposed as a form of psychological torture.

The prosecutors were going to argue she used us as human shields for her ego, that she’d rather risk our lives than admit she was wrong about the lockdown. The truth was more horrifying than any of us imagined that she saw us as props in her power game, even with a shooter in the building.

By day 56, the school district’s lawyers were in full panic mode and offered a $30 million settlement divided among all the families, admitting no wrongdoing, but acknowledging failures and oversight. Some families took it immediately because they couldn’t afford years of legal battles, but my parents and 12 other families held out for criminal justice, not just money.

Tyler picked me up 2 days later to visit the memorial that had grown outside the school. Hundreds of flowers and teddy bears and photos covering the front steps. Someone had left a copy of the student handbook with the lockdown procedures highlighted in yellow, a note attached that said, “These rules save lives when teachers follow them.

” We stood there holding hands, reading all the messages people had left when Tyler spotted something that made him squeeze my fingers so hard it hurt. Between two bouquets was a printed copy of Jake’s manifesto that the defense teams had just gotten access to. Five pages detailing Ms. Brown’s teaching methods like a psychological torture manual.

He documented the public humiliation, the deliberately confusing instructions followed by punishment for not listening, the gaslighting about things she’d said or done, example after example with dates and witnesses. The FBI had verified every incident he described through interviews with former students. That same week, Ms. Brown’s former teaching assistant from 2015 finally broke her silence in an interview with the local news. She’d quit after one semester because she couldn’t watch what Ms.

Brown did to students anymore, had even reported it to Principal Foster. But nothing was done because Ms. Brown had tenure, and the union would fight any disciplinary action. Another administrator who chose the easy path over protecting kids, another adult who could have stopped this years ago.

Frank, the custodian finding forgotten security footage on an old camera system is peak plot device saves the day energy. Though I suppose real life does sometimes hand you evidence gift wrapped with a bow when you need it most. Ben’s deposition happened on day 62 and his parents sent me the transcript later because they were so proud of how strong he was. His voice apparently never wavered when he said, “Miss Brown taught us that authority was more important than safety.

But that day, I taught everyone that survival is the only thing that matters.” The prosecutor asked if he blamed me for defying Mr. Brown. And Ben said I was the only adult in that room who acted like one. That a 17-year-old girl showed more leadership than a woman with 25 years of teaching experience. The FBI showed up at Ms.

Brown’s brother-in-law’s house the next morning with a warrant for witness tampering and obstruction of justice. after they caught him on a wire tap threatening Ben’s dad’s business partners if Ben didn’t change his testimony.

Her whole support network was crumbling as people realized the lengths she’d gone to protect herself, hiring private investigators to dig up dirt on students families, having her brother-in-law pressure anyone who might testify against her. Two weeks later, I sat at our kitchen table with Rebecca, the prosecutor, spreading out pages of notes for my victim impact statement. She pushed a legal pad toward me and told me not to hold back because the jury needed to understand everything Ms. Brown did that day.

Tyler sat next to me, his hand on my knee under the table while I wrote about how she kept us at our desks while a shooter walked the halls. I wrote until my hand cramped, then typed on my laptop, then wrote some more. The words came out angry at first, then sad, then just tired.

Rebecca read through my draft and nodded, telling me this would help the jury see the truth. Two days later, the court clerk called to say the trial was set for 3 months out. Three whole months of waiting. I tried going back to normal stuff like SAT prep and college applications.

But how do you write about your future goals when you almost didn’t have a future at all? The common app essay prompt asked about a challenge I’d overcome, and I just stared at the blank page for hours. Then on day 70, my phone blew up with texts from Ben. Ms. Brown had sent an email to his parents saying their son was confused about what happened and suggesting they get him therapy to help him remember correctly. The prosecutor had her arrested within 2 hours.

News vans showed up at her house and caught her being let out in handcuffs while she yelled about being persecuted for maintaining order. The judge called an emergency hearing the next morning. I sat in the gallery watching as the prosecutor showed the email and explained how Ms. Brown had violated her bail conditions by contacting witnesses. The judge didn’t even let her lawyer finish his argument before revoking her bail. Court officers moved toward her and she stood up fast, knocking over her water glass.

For the first time since this all started, I saw real fear in her eyes as they cuffed her. She looked right at me as they led her past the gallery, and I could see it hit her that she wasn’t in control anymore. Two nights later, mom found me at the kitchen table at 3:00 a.m. surrounded by college essay drafts. My Common App essay was about the day I chose to survive despite my teacher’s orders.

Mom read over my shoulder and said I didn’t have to write about this if it was too hard. I told her I did because this was who I was now. We both knew I’d never be the person I was before that day. The trial started 3 months later on a cold Monday morning. The prosecutor’s opening statement included playing the audio from my phone that I’d been recording for a class project.

You could hear the shots getting closer, students crying, and Ms. Brown’s voice clear as day, saying we were being hysterical and manufacturing fear. Several jurors put their hands over their mouths. Ms. Brown sat at the defense table in a gray suit, still acting like she was the victim.

The next day, I testified for four straight hours. The prosecutor walked me through every second of those 47 minutes, having me describe where everyone was sitting, what Ms. Brown said, how she blocked the light switch. Her lawyer tried to make me look like some rebellious kid who just didn’t like authority. But I stayed calm and just kept repeating the facts. When he asked why I defied a teacher’s direct order, I looked at the jury and said I chose to live while she chose her ego.

Nobody said anything for like 10 seconds. On day three, Tyler took a stand and talked about getting my texts about hiding in that supply closet knowing I was in danger. His voice cracked when he described the moment he thought I was dead because I stopped responding. Ms.

Brown’s lawyer objected, calling it emotional manipulation, but the judge said the jury needed to understand the trauma she caused by keeping students exposed. Tyler had to take three breaks to compose himself. Day four changed everything. The prosecution had enhanced the security footage audio using some FBI tech, and you could hear stuff we couldn’t make out before.

At time stamp 9:47 a.m., right after the first shots, Misty Brown’s voice came through crystal clear, saying, “If this is real, they deserve what they get for not respecting me.” A juror actually gasped out loud. Even her own lawyer looked shocked because this wasn’t in any of the discovery materials.

The judge had to call a recess when parents in the gallery started yelling. Day five, Miss Brown decided to testify against her lawyer’s advice. She sat in the witness box, insisting she maintained perfect order, that we were never in real danger, that she was being persecuted for having standards. She said she was protecting us from panic and that running around would have been more dangerous. The prosecutor let her talk for 20 minutes, then asked one question that made the whole courtroom go silent.

Did you recognize Jake Wilson’s voice when he was in the hallway outside your classroom? Ms. Brown froze completely, her mouth opening and closing like a fish. After maybe 15 seconds, she whispered yes.

The courtroom exploded with people shouting and crying, and the judge had to bang his gavvel over and over to get control. The prosecutor stood up slowly after things got quiet again and walked right up to Ms. Brown’s face. She asked the question everyone was thinking, but nobody wanted to hear out loud. Did Ms.

Brown know it was Jake Wilson in that hallway? The same Jake Wilson who filed three complaints against her last year. Ms. Brown’s hand started shaking and her face went from red to white to gray in about 5 seconds. The whole courtroom held its breath, waiting for her answer. Finally, she cracked and started yelling about how Jake needed to learn respect, just like all of us did.

The jury members looked at each other with their mouths open and one lady in the back row started crying. 3 weeks later, we all came back for verdict day and you could feel the tension like electricity in the air. The jury took 6 hours to decide, but when they came back, they found her guilty on everything.

23 counts of putting kids in danger, plus something called depraved indifference that sounded even worse. Ms. Brown fell down in her chair when they read it, and for the first time, she looked scared instead of angry. The judge said she could get up to 25 years, and the families of the three kids who died started sobbing.

2 weeks after that, I had to read my victim impact statement at sentencing. My hands were sweating so bad I could barely hold the paper, but I made myself look at her while I talked. I told her she taught me that being in charge without being smart about it was dangerous.

That trying to control people without caring about them was just being mean. I said I’d carry those 47 minutes with me forever, but she’d have to carry what she chose to do. The judge gave her 18 years with a chance for parole after 12. When the guards put the handcuffs on her, she turned to all of us and said she was just keeping standards.

Even then, she didn’t get it. And that was maybe the worst part of all. A month later, Tyler and I sat in his car watching workers put in new metal detectors and cameras at school. We were different now, stuck together by what happened, but also just different inside. Tyler took my hand and said, “We survived.

” And this time, it wasn’t a question. Ben went to the schoolboard meeting that spring and gave this amazing speech about fixing how they handled teacher complaints. His voice was strong and clear, nothing like the scared kid who almost stayed in his seat that day. He said, “No student should have to pick between their grades and staying alive.

” I started at State University that fall studying education policy because somebody needs to fix this stuff. My roommate didn’t know about what happened. And for a few weeks, I was just Briana instead of the shooting girl. It felt good, but also weird keeping that huge thing inside me.

They reopened room 203 as a memorial classroom in November and asked me to speak at the ceremony. Standing where Ms. Brown used to stand felt so strange, but I told everyone that protecting kids isn’t just about locks and drills. It’s about listening when they say something’s wrong.

Mom drove me home for winter break and we passed the school where kids were playing basketball like nothing ever happened there. I told her they looked so young and she said we all did back then. We both knew I’d never be that young again because innocence was another thing that died that day. Tyler and I met at our old coffee shop when we were both home from college for the holidays.

We still checked where the exits were and jumped when someone dropped a tray, but we were learning to live with it. Tyler held my hand and said we were writing new chapters now, which sounded cheesy, but also true. The scars would always be there, but we were more than what happened in room 203.

We were the kids who refused to stay in our seats when standing up meant staying alive. Thanks for letting me wonder about all this with you today. It’s been quite the journey asking questions together. Take care.

News

I was the black sheep who everyone ignored at family gatherings, until the day I…

I was the black sheep who everyone ignored at family gatherings until the day I inherited everything and…

What’s the most shocking thing you found out about the new student in school?

My mother always taught me that my best friend’s dad was a monster. When I found out the truth,…

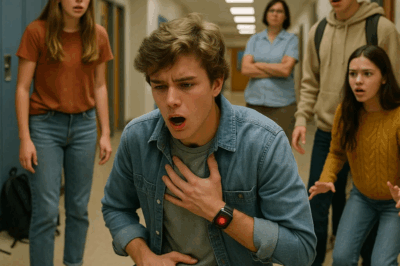

My school nurse said I was “faking it” then my heart stopped in the hallway.

My school nurse said I was faking it. Then my heart stopped in the hallway. The notification appeared on…

At the wedding, the son insulted his mother, calling her a “scoundrel” and a beggar, and ordered her to leave. But she took the microphone and gave a speech…

Svetlana Petrovna stood in the doorway of the room, barely opening the door — so as not to disturb, but…

She lowered herself beside his sidewalk table, quiet as a breath, the newborn tucked against her chest. “Please. I’m not asking for money—just a moment.” The man in the suit glanced up from his wine, not yet knowing that a few simple words were about to rearrange his entire belief system.

She sank to her knees beside his sidewalk table, one arm cradling her infant tight. “Please,” she said, voice steady…

CH1 “Bouquet Bombshell: Surprise Flowers from a Former Champion Ignite Romance Rumors Before Big ‘DWTS’ Win”

Backstage at the climactic finale of Season 34 of Dancing with the Stars, a simple bouquet sparked a media firestorm….

End of content

No more pages to load