In January 1942, a German reconnaissance patrol vanished near Leningrad.

Seventeen men went out.

No one heard gunfire. No one saw an ambush.

For a while, there weren’t even bodies.

Over the next six weeks, four hundred twelve more German soldiers fell in the same sector. One by one. Always a single shot. Always the same result: a clean wound to the head.

German intelligence started chasing ghosts.

They combed reports looking for signs of an elite Soviet sniper unit—some secret commando outfit from Moscow with state-of-the-art telescopic rifles and special training. But the man hunting them wasn’t a Spetsnaz prototype or a political favorite.

He was a Siberian shepherd.

He hadn’t seen a city until the draft board dragged him out of one frozen village and into the Red Army.

That pattern—ordinary rural men suddenly turning into terrifyingly efficient snipers—repeated itself across World War II. When historians went back after the war and tallied the “kill counts” of the deadliest snipers, something strange emerged: nine of the eleven most lethal came from farms, villages, and remote settlements.

Not academies.

Not big cities.

Fields. Forests. Mountains.

Even stranger: in a specialty where roughly three out of four snipers died, nearly two-thirds of these top eleven survived.

To understand why, you have to look at the kind of war they were thrown into—and the lives they’d led before it started.

Because what they were really doing wasn’t new.

They were hunting.

The only thing that changed was the prey.

The story really begins in a place that looks like the end of the world: Finland in the winter of 1939.

When the Soviet Union attacked Finland that November, the numbers were laughably lopsided. The Red Army marched in with about a million men. Finland had 300,000. The Soviets rolled in six thousand tanks. The Finns had thirty-two. Soviet air force: roughly three thousand aircraft. Finland’s: 114.

On paper, the whole thing should have ended in a couple of weeks.

It didn’t.

Because those numbers didn’t account for two things: winter, and the people who called that winter home.

Temperatures sank to –40°C. Theater-of-operations plans, built for mechanized warfare across flat land, hit a wall there. Diesel fuel turned to slush. Oil thickened into tar. Metal parts shattered, seized, or shrank. Men who didn’t know cold at that scale simply… stopped.

Finland was—and is—mostly forest and bog. No endless plains to let tank columns fan out. Just tree lines, frozen lakes, and little roads disappearing into woods.

The Red Army’s doctrinal pride and joy—deep battle, sweeping mechanized thrusts across open ground—had almost nothing to bite on.

The Finns had grown up in that forest.

They didn’t mass. They fragmented the enemy instead. Their “motti” tactics broke Soviet columns into smaller, isolated pieces—drive a wedge through a road-bound column, surround a section, starve and shoot it, then move to the next. At the individual level, they leaned heavily on something the Soviets hadn’t prepared for:

Men who had spent their entire lives stalking animals in conditions that casually killed professional soldiers.

In the middle of that frozen nightmare stood an unassuming little farmer who would go on to become a legend: Simo Häyhä.

If you saw Simo before the war, you wouldn’t have picked him out of a crowd. Five foot three. Quiet. A bit shy. A competitive marksman in civilian life, but mostly a farmer who liked his land and his dogs.

He understood something that the people writing manuals didn’t.

He refused a scope.

Every German sniper used one. Every Soviet sniper used one. Optics were considered mandatory; they were the cutting edge, the thing that separated precision shooters from ordinary riflemen.

Simo took one look at what they did in Finnish winter and said, “No thanks.”

Three reasons.

First: glass reflects light. In harsh winter sun on white snow, even a small flash from a lens can act like a flare saying, “Shoot here.” A telescopic sight glinting for half a second at 400 meters is a death announcement.

Second: scopes fog up. Moisture in the air and your own breath condenses on the internal surfaces, especially in extreme cold. That turns a five-hundred-dollar precision tool into a useless piece of glass right when you’re lining up.

Third: a scope forces your head higher above cover. To look through it, you have to raise your eye. Raise your eye, raise your helmet, raise your whole upper profile.

Every inch of extra skull sticking up over a snowbank is another inch someone like Simo can hit.

So he stuck with the simple iron sights on his Finnish M/28–30 rifle. Rear notch, front post. Nothing fancy. No reflection. No fogging. Lower profile.

He’d been shooting that way his whole life. At 300 meters, the difference between him and a scope user wasn’t that great.

That was just the beginning.

He also understood how to erase every other sign of a firing position.

He tamped and iced the snow in front of him so that when he fired, the muzzle blast wouldn’t kick up powder and make a telltale cloud. He wore head-to-toe white, not just a smock, but full winter camouflage, breaking up his outline.

And then there was the little trick that sounds like folklore until you picture the physics of –40°C air.

He stuffed his mouth full of snow while he waited.

Every breath a man takes in that cold comes out as fog. Vapor. Little puffs that can be seen at distance. Stuffing his mouth with snow cooled his breath, cut down visible vapor. One less thing giving him away.

He built, using only farmer logic and hunting sense, a near-perfect winter killing system.

He’d tell his comrades, “I’m going hunting,” in his quiet way and vanish into the tree line. An officer would step out of a trench to look at a map, maybe three hundred meters away.

Crack.

A machine-gun team would set up a position on a little rise at 250.

Crack. Crack.

A radio operator sprinting to a rear position to call in artillery fire at 200.

Crack.

On December 21st, he killed twenty-five Soviet soldiers.

On Christmas Day, thirty-eight.

By January, his count had passed 200. By February, more than 400. All with iron sights, in temperatures where exposed skin could die in minutes.

On the other side, things were coming apart in ways even hardened Soviet commanders found hard to process. They’d planned on casualties. They’d planned on frostbite. They had not planned on this—one man with no scope turning sectors of the front into zones nobody wanted to patrol.

They called him “Belaya Smert”—the White Death.

Soviet soldiers begged to be reassigned away from certain stretches of forest. Patrols missed their schedules. Orders were ignored. It wasn’t just the losses. It was the helplessness of it.

Artillery? You can hear it coming.

Tanks? You can see them.

But Simo’s shots just came. A flash. A sound—maybe. A man dropping. And then nothing.

A Red Army soldier named Pavel wrote home: “Mother, this is not war. This is hell. We march through these woods knowing he is watching. We fear the silence more than the shells. At least with shells, you hear them coming.”

Häyhä wasn’t the only one like that.

While Finland and the Soviet Union traded blood and frostbite in the north, something else was happening across the Eastern Front: the Soviet Union was building sniper warfare into an industrial process.

They trained over fifty thousand snipers during the war.

About two thousand were women.

Fifteen hundred of those women died.

Seventy-five percent mortality in the field.

Sniping was a spectacularly dangerous trade.

And yet, among the eleven deadliest snipers of the war—judged by confirmed kills—seven survived.

Around sixty-four percent.

Why?

The war itself didn’t distinguish between good and bad aim. What did was the background those men brought into uniform.

Men like Ivan Sidorenko.

He started as a collective farm worker from Ukraine. The Red Army turned him into a sniper. He turned himself into a force multiplier. His personal tally ran around 500 kills, but the bigger number was this: he trained more than 250 other snipers.

His students went on to kill thousands.

He understood that the real secret wasn’t fancy optics or “super-soldier” training. It was the mentality rural hunters brought to the job.

City-bred soldiers, even good ones, thought tactically: bounding overwatch, fire-and-maneuver, assault sectors. Hunters thought like predators: patient, terrain-driven, unconcerned with doctrine.

They waited.

They watched.

Then they struck once, decisively.

Snipers like Vladimir Chelnishev took that to extremes by pairing hunting mentality with intimate, almost obsessive knowledge of their ground.

He didn’t just know how to shoot. He knew exactly where he was shooting.

Every ravine. Every ruined building. Every stretch of road that always turned to mud first. When German units entered his area, they were intruders in someone else’s house. He already knew where they’d pause to light a cigarette, where a platoon would stack up to get out of wind, where a staff car would have to slow because of a bend.

He had 456 confirmed kills not because he was magically better at squeezing a trigger than every German sniper, but because he always had the advantage of home-field knowledge.

Others existed almost entirely in the shadows for decades.

Vladimir Salbiev—601 kills, if the Soviet paperwork from the 71st and 95th Guards divisions is to be believed. He likely died sometime in late ’44 or early ’45. No memoir. No interviews. No propaganda posters. The dead don’t write books. So he faded.

Vasily Kvachantze, from the Caucasus. 534 kills credited, plus one artillery piece taken out using incendiary rounds. His name appears in Soviet award citations, but barely registers in Western histories. A Tatar sniper named Akhmet Akhmetov—502 kills. Good enough to arm and send to the nastiest sectors. Not Slavic enough to promote after the fact.

Mikhail Budenkov—437 confirmed rifle kills. Additional kills with machine guns not even counted in his sniper tally. Nikolai Ilyin—494 kills. Fought at Stalingrad alongside Vasily Zaitsev, whose name Hollywood lifted up. Zaitsev was credited officially with 242. Ilyin had more than double that, but he died in 1943. Propaganda prefers living faces.

Then there was Fyodor Okhlopkov—429 confirmed, a Yakut from a village in far-eastern Siberia. He fought through the war. Survived wounds. Killed more than 400 Germans. When peace came, he went back to his remote village and virtually vanished. It took twenty years—until 1965—for him to be named a Hero of the Soviet Union.

Why so late?

Because he wasn’t ethnically Russian.

Even in a war marketed as “for all Soviet peoples,” propaganda had its favorites. Minority snipers were welcome as weapons. As symbols, less so. Russia wanted Slavic faces on its posters.

On the German side, the picture was very different.

Wehrmacht doctrine treated snipers as specialized assets. They trained a relatively small number deeply rather than a huge number adequately. One of the best-documented German snipers, often identified as Sepp Allerberger, an Austrian in a Gebirgsjäger regiment, had 257 confirmed kills with a Kar98k and a 4x scope. That made him deadly and famous in German accounts.

But he was still far behind the top Soviet and Finnish numbers.

It wasn’t that German individuals couldn’t shoot. It was that the German system never invested in sniper warfare at the same mass scale.

Soviet and Finnish practice armed hunters en masse.

German practice minted a handful of specialists.

Those different philosophies collided in a particularly telling way in the Winter War.

By January 1940, reports about Simo Häyhä had reached Soviet high command. One man. One rifle. Iron sights.

More than 400 kills.

It stopped being a tactical nuisance and became a strategic embarrassment.

The counter-orders came down hard:

Find him.

Kill him.

They started by sending in their own best snipers, people who knew the trade. They gave them scopes, warm clothing, priority artillery support.

They didn’t come back.

At least three Soviet sniper teams sent into Häyhä’s hunting grounds were found later by Finnish patrols as frozen bodies in the snow.

Then came the artillery.

If precision couldn’t solve it, saturation would.

They bombarded the forests where he was known to operate, hundreds of shells at a time. He wrote later that “the guns were loud today.” We don’t have a detailed diary from him, but surviving accounts suggest that he survived by refusing to do what a normal soldier would: dig in and make one spot “home.”

He didn’t stay put. He didn’t build permanent nests.

He moved like a hunter stalking game.

They escalated further—assembled a dedicated thirty-man counter-sniper unit, handpicked. Thirty of their best marksmen, with one mission: kill the White Death.

They went into the forest on March 5th, 1940.

On paper, thirty against one is not a fight. It’s an execution.

But those thirty were looking for a soldier.

He was looking for glints.

Through his irons, Häyhä saw the tell-tale spark of low winter sun on glass. Scope lenses. He knew what that meant. He used his Suomi submachine gun at closer ranges when opportunity presented, trading single icy rifle shots for savage bursts.

By the next morning, Finnish patrols found twenty-seven bodies.

They didn’t find him.

Finally, Soviet commanders gave up on precision and resorted to a methodical grid. They would simply erase the forest from the map with sector-by-sector artillery barrages.

On March 6th, 1940, the hundredth day of the Winter War, one random Soviet soldier got lucky.

He fired an explosive round.

It hit Häyhä in the face.

The round shattered on impact, obliterated his jaw, tore open his cheek, and left him looking like a corpse before he hit the snow. Finnish troops recovering their own wounded assumed he was dead until someone saw a leg move.

He was carried to a field hospital, comatose and unrecognizable. He stayed in that coma for eleven days. When he woke up, on March 17th, the war was over. Finland had lost some territory. The Soviet Union had “won”—on paper—but at the cost of around 126,000 dead and more than a quarter million wounded.

Hitler watched that debacle with interest.

If the Red Army had to pay that much blood for a slice of Finland, he reasoned, how well could it possibly stand up to the Wehrmacht?

The terror one farmer in white fatigues inflicted helped convince him the Soviet Union was, in his phrase, a “rotten structure” that would collapse with one good kick.

That miscalculation opened the door to Operation Barbarossa.

Instead of rolling over, the Soviets dug in. The war dragged on. Stalingrad happened. Kursk happened. And out of that crucible came the other snipers whose names never made it into movies:

Sidorenko. Chelnishev. Salbiev. Kvachantze. Akhmetov. Budenkov. Ilyin. Okhlopkov.

Häyhä survived his wound. Surgeons rebuilt his jaw with bone grafts and wire. His face bore the mark of that explosive bullet for the rest of his long life. Reporters occasionally tracked him down in later years and asked for his “secret.”

He gave them one word:

“Practice.”

After the war, he went back to his farm. Bred hunting dogs. Lived to ninety-six. He died in 2002, an old man who looked like anyone’s grandfather, not like the nightmare generations of Soviet veterans still flinched to recall.

When historians tally the numbers, the total for the eleven deadliest snipers of World War II goes past 5,000 confirmed kills.

Nine of them were Soviet. One was Finnish. One was German.

Nine grew up in the kind of places where if you wanted meat on the table, you went out in the cold and killed it yourself.

They weren’t laboratory-engineered warriors. They were people who’d spent years learning how to sit still, how to read land, how to recognize the moment prey makes a fatal mistake.

And that, eventually, is what the analysts had to admit.

That’s why so many of them lived.

Snipers taught solely by the army were often taught tactics: how to shoot, where to aim, when to withdraw.

The hunters brought something more primal.

They thought like the environment itself. They didn’t just follow doctrine. They absorbed the world around them until their presence disappeared into it.

The Germans had very good rifles, very good optics, excellent technical training. The Soviets had a massive pipeline of shooters and a doctrine that prized volume.

But the ones who survived the sheer lethality of sniper work were the men who approached it the way they had once approached deer or elk:

Infinite patience.

Absolute stillness.

And the unshakeable certainty that if you wait long enough, even the smartest prey will eventually step into the open.

The propaganda machines twisted some of the numbers. A sniper named Mikhail Surkov was credited with 702 kills; postwar analysis suggests the Soviets likely inflated that figure, possibly doubling or tripling it for effect. His real tally might have been in the 250–350 range. Still monstrous, but no longer unbelievable.

The inflation matters, because it shows how these men were used even outside the trenches. The survivors were turned into posters and stories. The dead became numbers in tables.

Especially if they were from “wrong” ethnic backgrounds.

Snipers like Okhlopkov had to wait decades for official recognition that their Russian counterparts received in months.

In the end, behind all the myths and the nationalism, the core pattern remains the same:

The deadliest snipers of World War II were not born in barracks.

They were built in forests and fields, on mountainsides and in frozen marshes—long before anyone gave them a uniform.

War gave them new targets.

It didn’t give them their skills.

News

Sister Deleted My Medical School Application — The Dean Was Watching Her Screen…

Chapter 1 – The Withdrawal The champagne bottle popped in the next room, followed by a chorus of laughter and…

My Mother-in-Law Sold My Family Home Without Asking. The Next Day, She Was Crying…

Chapter 1 – A Life That Worked My name is Emily, I’m forty-four, and most evenings my face is the…

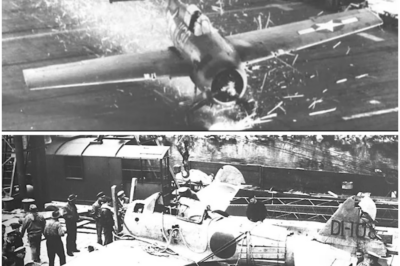

Midway 1942 How Japan Lost 4 Carriers in 5 Minutes WW2 Shocking Defeat

If only five minutes could decide the fate of an empire, what would history look like? At 10:25 in the…

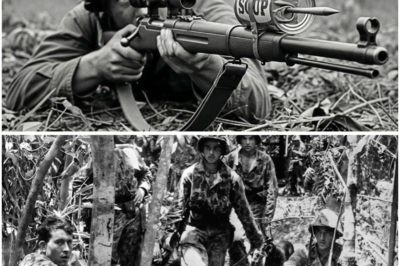

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Soup Can Trick” Took Down 112 Japanese in 5 Days

November 11th, 1943. 0530 hours. Bougainville Island, Solomon Islands. The mist hung low and heavy over the forward perimeter of…

The Japanese Pilot Who Accidentally Landed on a U.S. Aircraft Carrier

April 18th, 1945. Philippine Sea, two hundred and forty miles east of Okinawa. A lone Zero limped through the low…

Why Patton Was the Only General Ready for the Battle of the Bulge

On the morning of December 19th, 1944, a gray winter light leaked through the shattered windows of an old French…

End of content

No more pages to load