The morning sky over the Bismarck Sea looked calm—too calm. A sheet of blue glass stretching to the horizon, broken only by the distant hum of engines. For the men aboard the Imperial Japanese convoy on March 3, 1943, that sound should have been familiar by then: Allied bombers, high above the clouds, dropping harmless specks of metal that splashed wide or detonated far astern.

But this sound was different.

It was deeper. Meaner. Closer.

It was the growl of something the Japanese Navy had never faced before—an American bomber flying so low its propellers whipped spray from the ocean. A bomber whose nose bristled with machine guns like the jaws of a predator.

A bomber with fangs.

And when it arrived, everything the Japanese thought they knew about air attack tactics died in fire.

Losing a War From 20,000 Feet

In 1942, the Pacific was slipping through America’s fingers. The Philippines had fallen. Wake Island had been crushed. Japanese troops moved freely across the South Pacific, supplied by convoys shielded by destroyers and confident in the weakness of high-altitude Allied bombing.

The B-17s tried. They soared at 20,000 feet, released their bombs, and prayed the physics would cooperate.

It almost never did.

For every hundred bombs dropped, maybe one found a target. The rest churned the sea, harmless as rain. Convoy after convoy slipped through, delivering thousands of soldiers to reinforce the Japanese perimeter.

General Douglas MacArthur’s forces were being squeezed to death by ships they couldn’t seem to hit.

The problem wasn’t courage. It wasn’t aircraft. It was altitude.

And the man who finally solved it was not a general, not an engineer, not a graduate of any academy.

He was a mechanic.

A sixth-grade dropout.

A man with nothing left to lose.

Pappy Gunn: The Mechanic Who Refused to Quit

Paul Irving “Pappy” Gunn had spent twenty years as one of the Navy’s rare enlisted pilots. When the war began, he was running a small airline in the Philippines. Then the Japanese invaded.

His family was captured and thrown into an internment camp.

His home was gone.

His life had been stolen from him.

Gunn escaped to Australia, mourning everything he’d lost. The Army Air Forces commissioned him as a captain, and from the moment he put on the uniform, he cared about one thing:

Sinking Japanese ships—every last one.

Pappy understood something the high command didn’t want to admit.

You don’t sink a ship from the ceiling of the sky.

You sink it from eye level—where you can smell the salt and see the rivets in the hull.

And you do it with overwhelming, soul-rattling firepower.

The Birth of a Franken-Bomber

Working with a North American Aviation representative, Gunn started tearing apart bombers like a mad surgeon looking for a cure.

The B-25 Mitchell caught his eye. Fast. Rugged. Versatile. But its nose was wasted on a bombardier’s glass bubble and high-altitude equipment.

So Pappy ripped it all out.

Every wire. Every sighting mechanism. Every luxury.

He replaced the bombardier’s compartment with metal plates and hardpoints. Then he and his crew scavenged .50-caliber machine guns from crashed fighters and mounted them in the nose.

Four guns at first.

Then six.

Then eight.

Eventually, in some variants, eighteen forward-firing guns turned the plane into a horizontal chainsaw capable of spitting 8,000 rounds per minute.

A single B-25 now hit like three P-51 Mustangs charging side-by-side.

But firepower alone wasn’t enough.

Gunn needed a new way to deliver bombs—fast, brutal, unavoidable.

And so skip-bombing was reborn.

Skip Bombing: Stones Across the Sea

Pilots were retrained in a terrifying new tactic:

Come in low. Lower. Lower still.

Fifty feet above the ocean—lower than the masts of the ships they attacked.

At that range, the ocean wasn’t scenery. It was a wall of water rushing past your cockpit.

Pilots released 500-lb bombs at just the right moment. The bombs skipped across the waves like flat stones, smashing into hulls below the waterline where armor was weakest.

At the same instant, the B-25’s guns tore across the decks, shredding anti-aircraft crews before they could even swing their weapons.

This wasn’t bombing.

This was butchery delivered at 230 miles per hour.

General George Kenney saw the brilliance instantly and gave Pappy Gunn authority to modify every bomber he could get his hands on.

The Japanese would soon understand why that decision mattered.

March 3, 1943: The Convoy That Never Arrived

Eight transports. Eight destroyers. Nearly 7,000 Japanese troops bound for New Guinea.

It was enough manpower to crush Allied defenses and change the course of the campaign.

But at 10:15 a.m., salvation appeared on the horizon.

Thirteen B-25s.

Flying so low they cast shadows on the waves.

Their noses flashed first—long streams of fire reaching out like spears.

Then the bombs dropped.

Skipping. Hissing. Striking.

One transport erupted in flame. A destroyer rolled onto its side. Another ship vanished in a geyser of steam as rounds tore through its boilers.

In 15 brutal minutes, the convoy ceased to exist.

Eight transports and four destroyers sank or burned.

Of 6,900 troops aboard, fewer than 1,200 survived to reach land.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea wasn’t a battle.

It was an execution.

The Aftermath: When the Sea Belonged to America

Japan never again attempted to send a major convoy across the Bismarck Sea.

Pappy Gunn’s invention had made the cost unbearable.

The gun-nosed B-25 became the ultimate ship killer—a flying weapon the Japanese Navy had no doctrine to counter and no time to prepare for.

General Kenney later wrote that the battle marked the moment American air power truly dominated the Pacific.

At the center of that turning point stood a mechanic from Arkansas who refused to accept defeat.

A Mechanic Who Changed a War

Pappy Gunn didn’t have rank.

He didn’t have resources.

He didn’t have his family to come home to.

What he had was anger. Creativity. And the stubbornness to break every rule in the book.

With scavenged guns, sheet metal, and a vision no one else dared try, he built a bomber with fangs—and gave America a weapon that reshaped the Pacific War.

Sometimes victory doesn’t come from the top down.

Sometimes it comes from a man in a hangar, sleeves rolled up, turning a medium bomber into a monster.

And when he was done—

the ocean belonged to the Mitchell.

News

The tragic deaths of real-life Band of Brothers veterans George Luz, David Kenyon Webster and Bull Randleman.

By the time the world met them on television, most of them were already gone. The men of Easy Company…

The General Who Never Got the Medal of Honor and Still Became the Most Famous Marine in History

The wind coming off the frozen hills of North Korea cut like a knife. It was December 1950, somewhere near…

The Most Dangerous Woman of World War II – Lady Death in World War II

At 5:47 a.m. on August 8, 1941, in the shattered streets of Beliaivka, Ukraine, a 24-year-old history student crouched behind…

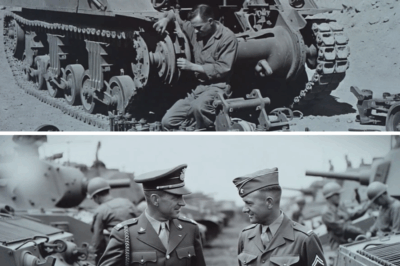

The Mechanic Who Turned an Old Tank Into a Battleground Legend

War had a way of turning machines into ghosts. In March 1943, somewhere in the empty heat of the North…

Kicked out by her own family on Christmas with just one sentence—“You’re nothing to us”—Rowena walked away in silence. But five days later, her phone lit up with 45 missed calls. What changed? In this gripping family drama story, discover the buried secrets, the stolen inheritance, and the power of reclaiming your worth. This is more than a holiday betrayal—it’s a reckoning.

Part 1 – Before the Sentence Hi. My name’s Rowena. My family kicked me out on Christmas night. No screaming.No…

Colorado Mourns State Sen. Faith Winter: Environmental Champion, Policy Architect, Mother of Two, Killed in Five-Car Crash

Colorado’s political and civic landscape was jolted Wednesday night by the sudden death of State Sen. Faith Winter, a Democrat…

End of content

No more pages to load