You hear it before you see it.

A low, distant growl that never quite stops. Every few seconds it swells, sharpens, becomes something else—a ripping crack in the air, the sound of branches exploding over your head. Then a pause. Two heartbeats. Three. Then it starts again.

Late autumn 1944. Hürtgen Forest.

The trees are ruined things—splintered trunks, ragged stumps, crowns torn away. The ground is a carpet of frozen mud, broken roots, and men who have learned to fear the sound of wood being hit harder than the sound of bullets.

For months, German officers had told each other the same comforting lie: American artillery is clumsy.

They had studied Allied fire in North Africa, measured British barrages in Italy, and read every captured American field manual they could lay hands on. They knew the patterns—long delays between spotting and firing, slow corrections, batteries that wasted ammunition trying to find the range. In a forest this dense, they believed, Allied guns would be half-blind and easily avoided.

They walked into Hürtgen expecting mud and blood and trees.

They did not expect mathematics.

The first sign that something was wrong was subtle. An observer in a forward German company noticed it before anyone else.

“Artillerie!” someone shouted when the first rounds came in.

He braced for the usual pattern. An initial bracket, wild and long. Then corrections, walking slowly toward his line. Time to report. Time to shift. Time to scatter.

It didn’t happen.

The first salvo landed close. The second was on target. The third crept thirty meters to the flank. In less than four minutes, American fire had bracketed a position it should have taken ten minutes to find.

Somewhere behind the American lines, in anonymous canvas tents, men with radios and plotting boards had reduced the age-old art of gunnery to an engineering problem.

They called them fire direction centers.

A forward observer, a single lieutenant with binoculars and a radio, would call in a grid coordinate and a target description.

“Horse Shoe One, this is Fox Three. Infantry in the open, grid 217463, moving east, over.”

Back in the fire direction center, a clerk would write the numbers on a board. Two men would bend over a map. One would slide a metal protractor across the paper while another tapped a slide rule, muttering ranges and angles.

“Battery A, B, C, deflection three-seven-two-four, quadrant three-two-seven, charge three, stand by fire for effect.”

Three miles away, nine guns would elevate almost simultaneously.

The Germans didn’t see any of that. All they saw was the impact.

Shells from three different batteries, at three different distances, all arriving within the same two-second window.

They had a name for it: time-on-target. To a man standing under it, it felt like the world ending in a single breath.

There was no long-drawn warning whistle. No rumbling approach. One second the forest existed. The next it was flying apart.

Later, when officers inspected the aftermath of a time-on-target mission, they refused to believe a single battalion had fired it. They thought at least a division’s artillery must have been committed. Maybe more.

They were wrong.

Most of that destruction came from a single division’s guns, working through a common brain and a common clock.

German doctrine had always treated the American 105 mm howitzer as a light gun.

It could suppress, certainly. It could scare men out of trenches, break up an advance. But against dug-in defenders, against troops in deep foxholes and concrete bunkers, it was supposed to be a nuisance, not a killer.

That assumption died in the Hürtgen.

The shells rarely exploded in the ground. They exploded in the trees.

The Americans had brought time fuses and variable time (VT) fuses to the front, and their gunners knew how to use them. Instead of punching into soil and wasting half their blast upward into empty air, 105 rounds were set to burst just below the forest canopy.

The effect was obscene.

Each airburst turned the trees into a thousand knives. Wooden splinters, some longer than a man’s arm, scythed downward at supersonic speeds. Men crouched in trenches or behind logs found no safety; the fragments came from above, angled in from every direction, bouncing off trunks and ricocheting into places no one had thought to protect.

Veterans gave it a name: the hell of wooden needles.

German gunners tried to copy it. They had airburst fuses of their own, but their timing was inconsistent, their manufacturing inferior. Their shells burst too high, too low, sometimes not at all. Their artillery had always been accurate; now they discovered accuracy was only part of the equation. Fuse quality and volume mattered as much as barrels and aim.

The Americans had both.

In a typical sector of the Hürtgen, a German division might begin a battle with a few hundred shells per battery. Once fired, those guns went quiet. The shells did not come back.

On the American side, a single artillery battalion rolled forward with enough ammunition for three days of sustained fire: thousands of rounds stacked like cordwood around each gun position. Behind them, trucks ran day and night from depots that could supply a hundred battalions at once.

German officers who captured American ammunition dumps were stunned. They walked between stacks of crates higher than a man, warehouses full of high explosives. What they were seeing, though they didn’t yet fully grasp it, was the final link in a chain that stretched back across the Atlantic, to factories in Pittsburgh and Detroit, to steel mills and powder plants and rail yards.

Every American shell on the German front was the end product of an economy that had been turned into a weapon.

The Germans had always prided themselves on their forward observers and their tactical doctrine.

They had trained for years to make artillery responsive. Observers were taught to move with the infantry, to call down fire with precision, to adjust with few rounds.

Their problem in late 1944 wasn’t that their observers were bad. It was that American observers were plugged into a system their manuals had never imagined.

American forward observers didn’t just request fire. They controlled it.

A lieutenant on a ridge with a field telephone could talk not just to “his” battery, but to any gun within range.

“Get me all the guns that can reach 219472,” he would say, and the fire direction center would oblige.

Battery boundaries? Division boundaries? Corps boundaries? These were administrative lines, not tactical limits. If a gun could reach a target and ammo was available, it could be brought to bear. The math made that possible. Radio made it easy.

One small liaison plane—a Piper Cub or Stinson L-5—circling above the trees could do the work of a dozen ground observers. From his tiny cockpit, an artillery pilot could see movement beyond every ridge, spot muzzle flashes, trace vehicle dust trails. He didn’t care which division’s guns answered his calls. He just gave grids and corrections.

The Germans began capturing these men in ones and twos. When interrogated, they described a network of fire direction centers, sound-ranging batteries, flash-spotting posts, radar sets, plotting boards. It sounded like science fiction.

Their interrogators wrote down the details, shook their heads, and said it was overstated.

It wasn’t.

By the time the German Army launched its surprise offensive in the Ardennes in December 1944, their commanders had convinced themselves that winter would level the scales.

Snow would dampen sound. Fog would blind observers. Frozen ground would limit fragmentation.

Tanks and infantry, not artillery, would decide this battle.

The weather cooperated at first. Low cloud grounded American fighter-bombers. Thick fog meant no aerial spotting. German armored columns pushed through the woods along narrow roads, engines muffled, headlights hooded.

Then the shells started falling.

They came with the same mechanical precision that had startled the Germans in the Hürtgen.

How?

The Americans had prepared.

Meteorological teams along the front took constant readings: temperature, air pressure, wind speed at various altitudes. Those numbers went into firing tables that had been printed months before, updated and annotated by men who understood that steel doesn’t care if the sun is shining.

Guns were insulated. Powder was warmed. Fire direction centers carried cold-weather corrections. Pre-registered targets were marked on maps, each with its own firing data already calculated.

In the mist and snow, sound-ranging teams listened.

When a German battery fired, its shell made a distinct supersonic crack as it passed. Microphones spaced along the front recorded that sound. The slight differences in arrival times told American technicians exactly where the shell had been fired from. Within seconds, their own guns had those coordinates.

German batteries that fired more than a handful of rounds rarely got the chance to fire again.

One German officer wrote that in the Ardennes, “our guns died in silence.” Not from counter-battery duels, but from a system that saw their muzzle flashes, listened to their shots, and erased them before they could displace.

By early 1945, German operations officers had begun to describe American artillery in new ways.

They stopped talking about “barrages” and started talking about “atmosphere.”

Fire didn’t come by request. It was simply there, all the time, like weather.

A company moving along a forest road would be hit within minutes of being spotted. A platoon that tried to shift positions in daylight found shells walking along its new route. Machine guns that opened fire were met with immediate response.

Movement itself became a risk calculation.

The safest place on the battlefield was often exactly where you were now, provided the Americans hadn’t seen you yet. The moment you moved, you increased the chances that some forward observer, some liaison pilot, some sound-ranging post would notice—and that somewhere, someone with a slide rule would decide to stop you.

German diaries from the Roer fighting read like the journals of men caught in a natural disaster.

“Our trenches crumbled in the bombardment,” one wrote. “The trees above us broke like matchsticks. We could not move; every time we tried, new shells fell. We could not survive if we stayed; we could not survive if we left.”

They were not facing a handful of batteries with finite ammunition. They were facing a machine.

The United States had built an artillery system where no gun ever ran out of food for long, no battalion ever fired alone, and no forward observer was ever isolated.

And when the final cross-river operations came, the scale reached levels that still stagger historians.

Before crossing the Roer, American corps unleashed fire missions counted not in dozens of rounds, but in hundreds of thousands. On some sectors, quarter of a million shells fell in a few hours. The ground literally heaved. Bunkers shook apart. Riverbanks slid into the water.

German officers surveying the abused landscape afterward believed they had faced the heaviest siege artillery in the Allied inventory.

They hadn’t.

Most of those shells were 105s.

If you strip away the numbers and maps, what remains is simple.

The Germans bet on doctrine—on cleverness, training, experience, courage. All the things that had carried them from Poland to the gates of Moscow.

The Americans bet on physics and factories.

They were not better gunners. Individually, they were often no more skilled than their German counterparts. But they did something the Germans didn’t.

They treated artillery as a system, not a collection of guns.

Forward observers, liaison pilots, sound rangers, fire direction centers, ammunition dumps, truck drivers, powder plants—all of it was part of the weapon.

When a German officer in the Hürtgen insulted American artillery as “crude mass fire,” he wasn’t entirely wrong. It was crude, in the sense that a hammer is crude.

It didn’t have to be subtle. It just had to be everywhere, all at once.

By the time he realized that, he was already under the hammer.

In the end, German officers stopped asking how to beat American artillery and started asking how long they could live under it.

They wrote of steel rain and wooden needles, of barrages that lasted twelve hours, of forests shaved down to stumps, of men who went mad from fear of branches exploding overhead.

They had entered a war where courage mattered less than supply tonnage, where the quality of an optical fuse mattered more than the quality of an NCO. A war where your best defensive doctrine could be undone by a captain with a radio and a grid coordinate.

Their armies had been designed for maneuver, for Blitzkrieg. They found themselves, in late 1944 and early 1945, reduced to digging and praying under a sky that never stopped falling.

One German artillery officer put it plainly in a postwar interview:

“We weren’t beaten by American soldiers,” he said. “We were beaten by American steel. Their infantry walked where their guns had already won.”

In the ruined woods of the Hürtgen, on the foggy roads of the Ardennes, on the banks of the Roer and the Rhine, the lesson was the same.

Artillery wasn’t supporting the American advance.

The advance existed to exploit what the artillery had already decided.

News

After three years I came home and found my daughter sleeping in our laundry room

PART ONE: THE HOUSE THAT WASN’T MINE ANYMORE The rental car smelled like artificial pine and stale coffee, but I…

CH1 U.S. Navy’s FIRST Blind Strike: Admiral Lee Hits Target Beyond Sight

The night was so black it felt solid. November 14th, 1942. 0320 hours. Ironbottom Sound, south of Guadalcanal. Admiral Willis…

CH1 Joy Reid Reposts Viral Video Calling “Jingle Bells” Racist, Sparking Fresh Debate Over Christmas Classic

NEW YORK — Former MSNBC host Joy Reid reignited a familiar culture-war debate this week after reposting a viral video…

CH1 “The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming”

The searchlights swept the black water like fingers. Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse…

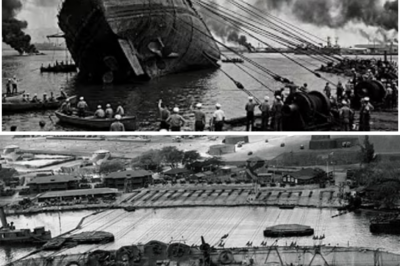

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

CH1 They Mocked His “Medieval” Airfield Trap — Until It Downed 6 Fighters Before They Even Took Off

The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42. Then another. Then four more in rapid succession. Six RAF fighters…

End of content

No more pages to load