At 07:42 on March 6th, 1945, Corporal Clarence Smoyer crouched inside the turret of an M26 Pershing in the rubble-choked streets of Cologne, watching a German Panther slowly traverse its long 75 mm gun toward the intersection where two American Shermans had just stopped. He was 21 years old, with seven months of combat behind him, five enemy tanks destroyed, and a lifetime’s worth of fear sitting in his gut as smoke began to pour out of the lead Sherman’s crew compartment two streets away. The Panther fired twice, both rounds punching through the Sherman’s gun shield within inches of each other. Three crewmen died where they sat. The commander tried to bail out, his left leg gone below the knee. Clarence had grown up in coal country in Paville, Pennsylvania, where his father worked the mines and quiet boys learned to keep their heads down. He’d hunted rabbits once as a kid, shot one, and felt sick afterward. Now he was behind the sight of America’s newest and most powerful tank, one of only twenty Pershings on the entire European continent, leading a column into a city that German propaganda had promised to fight for “house by house, floor by floor.”

“Target, Panther, one o’clock, two blocks ahead,” Staff Sergeant Robert Early said over the intercom, his voice steady in Clarence’s headphones.

“On,” Clarence answered, nudging the turret traverse, feeling the huge 90 mm gun swing toward the cathedral square.

By March 1945, thousands of American Shermans had been wrecked by German guns. Everybody knew the numbers: Panthers weighed ten tons more than a Sherman and Tigers even more; German 75s and 88s could kill a Sherman frontally long before a Sherman’s 75 mm could hope to penetrate German armor. The Battle of the Bulge had been the breaking point. Sherman crews fought bravely and died quickly in the Ardennes snow while Panthers and Tiger IIs tore through American lines. For years, Army Ground Forces under Lieutenant General Leslie McNair had insisted the Sherman was “good enough” and that dedicated tank destroyer units would handle heavy German armor. Tanks, they said, were for supporting infantry, not dueling other tanks. German doctrine—and the battlefield—disagreed.

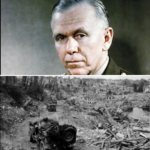

The heavy-tank solution had existed on paper since 1942. The T26 program had produced prototype after prototype, each a little better than the last, each a little heavier, each stamped “not necessary” by McNair’s staff. The Sherman worked fine in North Africa, they argued. Why change? Normandy and the Bulge made that answer indefensible. By January 1945, the first twenty T26E3s—soon to be called M26 Pershings—arrived at Antwerp. Ten went to Third Armored Division, ten to Ninth Armored. The Pershings reached a maintenance area near Aachen on February 17th, and division commanders sent their best crews—men who had survived Sherman fighting—to learn the new machine.

On the gunnery range, Clarence met the 90 mm gun. The controls were similar enough to a Sherman’s that his hands knew where to go without thinking. The recoil wasn’t. Major General Maurice Rose, Third Armored’s commander, stood about twenty feet behind the Pershing when Clarence was told to test-fire at a farmhouse twelve hundred yards away.

“Hit the chimney,” someone told him.

Clarence centered the crosshair on the brick stack, squeezed the trigger. The world became white and noise. The muzzle blast punched the air so hard that Rose and his staff hit the dirt like somebody had swung a giant invisible fist through them. The chimney disintegrated. Clarence re-acquired, hit two more chimneys farther away. When the smoke cleared, Rose stood up, brushed dust off his jacket, looked at the shattered masonry and the sweating 21-year-old kid in the turret, and grinned.

“That’ll do,” he said.

The Pershings went to war.

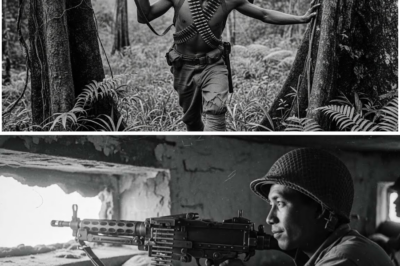

Cologne had been Germany’s fourth-largest city, a million people before the bombs started falling. Two hundred and sixty-two Allied air raids turned most of it into jagged stone and twisted tram rails. By early March 1945, maybe forty thousand civilians remained, living in cellars and tunnel systems beneath streets where the dead outnumbered the living. The only things that seemed untouched were the twin Gothic spires of Cologne Cathedral, rising above the ruins like black fingers. Third Armored entered the city’s outskirts on March 2nd. For four days, they fought block to block. German defenders used underground pedestrian tunnels—what GIs called “mouse runs”—to appear behind American positions, fire, and vanish. Snipers worked from church towers and factory chimneys. Panzerfaust teams waited in doorways and coal chutes for any tank foolish enough to pass with its hatch open.

The Pershing was a blessing and a curse in that environment. Thick frontal armor and that 90 mm gun gave Clarence a fighting chance against Panthers and even Tigers, but in narrow streets and blown-out intersections, ten extra tons meant bridges collapsed, basements caved, and the tank could be boxed in by rubble that a lighter Sherman might squeeze through. Eagle 7—the crew’s nickname for their new tank in honor of the Philadelphia Eagles—led the way into the city center on March 6th. Being first in line meant every ambush was meant for you.

They moved slowly through a canyon of broken shop fronts and office buildings. Mannequins lay face-down in glass and plaster dust. Overturned trams rusted in the gutters. Every second-story window was a question: Panzerfaust or broken curtains? Every basement shutter might hide an 88 poked through blasted masonry. Clarence rode with his eye glued to the telescope, the turret traversed a few degrees left or right as they crept forward, 90 mm barrel hunting shadows.

The radio crackled.

“Third Armored to Eagle 7. German armor reported near the cathedral square. At least two Panthers, possibly a Tiger. F Company tanks are attempting recon.”

Early acknowledged, the Pershing’s engine note rising as they rolled toward the spires that stabbed the gray morning sky. Somewhere ahead, two Shermans from F Company nosed into the cathedral district without infantry support. That was dangerous in any city, suicidal in Cologne, but nobody had spare riflemen to babysit them. Their orders, like Eagle 7’s, were simple and deadly: find German tanks, take them out, hold the ground.

The first sign that everything had gone to hell was the sound—two deep cracks, the way only a high-velocity tank gun sounds. The radio lit up with frantic voices.

“Sherman hit! Sherman hit! Crew bailing—my God—”

Another crack, then nothing but static. Eagle 7’s street curved, the cathedral’s bulk looming ahead as they came into a broader avenue. Early ordered a halt a block short of the square. He and a Signal Corps sergeant with a film camera—Jim Bates—climbed down and pushed forward on foot to scout. Clarence waited in the turret, bladder icy, hands on the turret control, every muscle poised.

Early reached the corner, peered around with binoculars. In the square in front of the cathedral, a Sherman sat in the open like a dead animal, gun elevated, hatch open, smoke pouring out. Beyond it, tucked back at a side street like a spider in a web, sat the Panther. Slate-gray, low, lethal, gun pointed exactly where the Shermans had come from. There was no way forward across that plaza without walking into its sights.

He slid back to Bates, pointed down a side street that ran parallel to the approach.

“We go around,” he said. “Hit him from his right. He’s pointing north. We come in from the west.”

Early returned to Eagle 7 and dropped into the turret.

“We’re going to flank him,” he told the crew. “McVey, take the next right, stay low. Clarence, traverse right, be ready. When we pop out, you’ll have his side. You’ll have one shot before he reacts. Make it count.”

Clarence swallowed and answered.

“Yes, sir.”

McVey eased the big tank around the corner into the side street. The Pershing barely fit, steel skirts scraping brick. Rubble forced them around shell holes and collapsed doorways. The engine’s growl echoed between shattered walls, a sound no Panther crew could miss for long. In the gunner’s sight, Clarence saw nothing but bricks and shadows, but he could feel the geometry in his head. When they reached the next intersection and turned left, the world would explode into the square and the Panther should be dead ahead, turret pointing away, side armor exposed.

“Ready!” Duriggy called, ramming an armor-piercing shell into the breach.

“On,” Clarence said, the 90 already traversed ninety degrees to the right, his eye welded to the reticle.

They reached the intersection. McVey didn’t slow. Eagle 7 surged out into open space, and the world widened. The cathedral towered above them. The wrecked Sherman lay off to their left, smoking. And there, exactly where Early had said, sat the Panther—only its turret was already moving, gun swinging toward them faster than Clarence liked.

He didn’t wait for textbook conditions. The Pershing was still rolling, the sight picture shaking, but the Panther’s gun was nearly on them. He aimed low on the turret face and fired.

The blast punched his chest. Through the ringing in his ears and the jump of recoil, he saw sparks flare on the German’s turret front. The shot hit, high and a little off to the side. Good hit. Not a kill. The Panther lurched but stayed in the fight.

“Up!” Duriggy shouted, already shoving the next round forward.

McVey brought the tank to a halt in the middle of the intersection—dangerous, but essential. A moving gun was a guessing game. A still gun could be precise. Clarence dropped the sight a fraction, aimed at the flat plate where the turret sat on the hull, the Panther’s right side now nicely angled to him at about ninety yards. He knew the numbers by heart: 90 mm AP against 40 mm side armor at that distance wasn’t a question, it was a statement.

He squeezed again.

The second shot hit just below the turret ring. In the sight, Clarence watched the German tank jerk, saw a black hole bloom in the side armor, saw dust and flame push out the far side. A moment later, the third round drove the point home, punching in at nearly the same point. Fire whooshed out of seams, licked up the back deck, and then the machine that had owned that square for fifteen minutes was nothing but black smoke and orange flame.

Up in a scarred building overlooking the square, Jim Bates caught it all on 16 mm film. Years later, people would watch the sequence in newsreels—Pershing lunging into frame, Panther turning, muzzle flashes, then flames. Some called it the moment American armor finally answered Germany’s heavy cats on equal terms. For Clarence, it was just forty-odd seconds where his world shrank to a sight picture and a trigger.

The battle around the cathedral wasn’t finished. As Eagle 7 pushed deeper into the city that afternoon, another encounter dug itself into Clarence’s memory and never left. Coming down a different street a few blocks away, they caught sight of a black sedan racing across an open intersection. Civilian car, but in this war, staff cars carried officers and runners—legitimate targets. Clarence saw it. So did a hidden German Panzer IV sitting behind the corner of a smashed residential building.

“Car at twelve!” someone shouted.

Clarence traversed and hosed the intersection with coaxial machine-gun fire. At the same instant, the Panzer’s hull MG roared. The sedan caught two storms of bullets at once. Glass exploded. The car slewed sideways and slammed to a stop. A figure tumbled out of the passenger door and crumpled on the cobblestones. The driver never moved. Clarence saw only a body. At the time, that was all he let himself see.

The Panzer fired, missed, and reversed out of sight behind the half-standing building. In that instant, Clarence made another decision. He couldn’t see the German tank anymore, but he could see the building holding it.

“HE!” he called.

Duriggy jammed a high explosive shell into the gun. Clarence aimed low at the building’s corner, where the remaining wall met the ground—a weak point in any structure, whether it was a barn in Pennsylvania or a bombed-out hadershaus in Cologne. He fired.

The shell hit and blew out the corner. For a second, nothing happened. Then gravity remembered its job. Four stories of brick, plaster, beams, and stone began to sag, then collapse. The whole building folded in on itself and poured into the space where the Panzer sat. A man named Gustav Schaefer, an eighteen-year-old machine gunner inside that tank, would spend the next frantic minutes clawing out through a turret hatch with his commander as the building entombed their vehicle. They got out. The rest of their crew did, too. They slipped away through the ruins, crossing the Rhine that night to surrender days later. Clarence didn’t know any of that. All he saw was a cloud of dust, a crushed building, and a silence where a tank had been.

Cologne fell within days. The Hohenzollern Bridge was secured before German engineers could drop it into the river. The cathedral still stood, blackened but unbroken, above a city that looked like the surface of the moon. Eagle 7 kept moving, kept fighting. The war moved east toward the Rhine and beyond. Somewhere near Paderborn later that month, Major General Rose, the man who had laughed in the dust of that training range, was killed by German fire in a roadside encounter with a tank. Men in Third Armored felt that loss like a physical blow. Clarence heard about it over the radio and just stared at the horizon. Leaders die in war. So do gunners.

The war ended. Clarence went home.

He went back to Pennsylvania, to cement dust and shift work in a plant instead of coal dust and mine shafts like his father. He married Melba, the girl back home. They had three kids. He went to work, paid bills, fixed broken stuff. People in town knew he had “been in tanks,” knew he’d “been over there,” but mostly they saw a quiet man who showed up on time and didn’t talk much about the past. He tried not to. But the war didn’t stay put. It came back at night.

Always the same images: the Panther burning in front of the cathedral, the cramped turret, the smell of hot oil and cordite—and the black sedan, spinning, glass blowing out, the person in the passenger seat tumbling in slow motion onto cold stone. At the time he hadn’t known. Later, he feared. Eventually, thanks to a documentary and an old friend’s reel of film, he knew.

In the mid-1990s, Clarence sat in his living room and watched Jim Bates’s old footage cleaned up for a TV documentary. On the screen, he watched his younger self’s tank burst into the square, watched the Panther die again, watched that black car flash through the frame, watched his own machine gun reach out between him and the German Panzer—and watched a woman fall from the passenger door.

Her name, he later learned, was Katharina Esser. Twenty-six. The youngest daughter in her family. She’d stayed in Cologne to care for her parents while her sisters married and left. She worked at a grocery, took night classes in home economics. On March 6th, 1945, she tried to flee the city with her boss. They picked the wrong intersection, at the worst moment of the worst day.

Clarence carried that knowledge like a stone in his chest for another twenty years, until a German journalist tracked down the story, connected names and footage, and invited him to Cologne in 2013. Clarence was eighty-nine. He could barely walk without help, but he went.

He expected an empty cemetery and his own guilt. He found another old man waiting: Gustav Schaefer, the former Panzer gunner whose tank had fired on the same car from the opposite side of the intersection, whose vehicle had been buried under the building Clarence had knocked down.

They shook hands in front of the cathedral both had once fought around, then walked together to a grave marked with Katharina’s name in a mass burial. They both brought yellow roses. Neither knew whose bullets had killed her. In truth, it could have been either, or both, or flying fragments from shattered stone. It didn’t matter. They both felt responsible. They both apologized to a woman who couldn’t hear them.

Clarence knelt to lay his flowers and lost his balance. Gustav, the man who had once been his enemy, stepped in without thinking and caught him. Two men who had tried hard to kill each other sixty-eight years earlier stood there arm in arm above the consequences of their war.

They became friends. Letters went back and forth. When Gustav died in 2017, Clarence sent flowers.

“I will never forget you,” he wrote. “Your brother in arms, Clarence.”

Two years later, in Washington, D.C., an old man from Pennsylvania finally stood in front of a different kind of crowd. On September 18th, 2019, in the Capitol, Clarence Smoyer received the Bronze Star with “V” for valor—seventy-four years after the duel in Cologne. He was the last surviving member of Eagle 7’s crew. The other men’s medals were handed to their families. He accepted his quietly, as he’d done everything else.

When Clarence died in 2022 at age ninety-nine, the obituaries spoke of the “tank gunner who destroyed a Panther in front of Cologne Cathedral.” They showed the famous frames from Bates’s film—fire, smoke, steel. They talked about the Pershing, the first heavy American tank, about doctrine finally catching up to reality.

They rarely talked about the black car and the young woman whose name he’d written on his heart for decades. They didn’t always mention the German gunner who caught him when he fell in the cemetery. But somewhere in Cologne every March 6th, yellow roses still appear on Katharina Esser’s grave.

Someone remembers.

Someone still apologizes.

News

CH1 Hillary Clinton Allegedly Deflects Federal Probe by Pointing Investigators Toward Daughter Chelsea in Clinton Foundation Grant Scandal

December 14, 2025WASHINGTON — In a stunning development that has rocked political circles and reignited long-simmering controversies surrounding the Clinton…

My Dad Asked Why the Fridge Was Empty And My Husband’s Answer Blew the Entire Family Apart

The Empty Refrigerator When my father arrived to pick up Ben for their weekend together, he did what grandfathers do—he…

The Unexpected Reply: What a Mother-in-Law Told Her Daughter-in-Law When She Demanded the Rent Be Paid

The phone felt warm in my hand, a stark contrast to the ice that suddenly filled my veins. I had…

CH1 The Secret Shell That Turned German Panthers Into Burning Metal Coffins

On the morning of December 26th, 1944, Technical Sergeant James Robert Caldwell pressed his eye to the scope of his…

CH1 The Apache Sniper Who Hit Targets Nobody Could See — Witnesses Still Argue About Okinawa (1945)

They started calling him the ghost long before anyone knew his name. On Okinawa, in the shattered ridgelines north of…

CH1 This 18-Year-Old P-38 Cadet Slipped Into a Spin And Discovered a Trick That Outturned 5 Enemy

At 18,000 feet over the California desert, the P-38 Lightning snapped, rolled, and went end over end. The horizon turned…

End of content

No more pages to load