At 09:58 on April 8th, 1940, Lieutenant Commander Gerard “Roope” Roope stood on the open bridge of HMS Glowworm, peering into a wall of cold Norwegian fog, when a shape the size of a cliff slid out of the gray.

The German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper was closing fast.

Roope was thirty-five. He’d spent five years commanding destroyers. That morning, every bit of that experience told him the same thing: his ship was hopelessly outmatched. Hipper displaced 14,000 tons and carried eight 8-inch guns. Glowworm displaced 1,350 tons and carried four 4.7-inch guns when everything was working—which it wasn’t. Hipper outweighed Glowworm ten to one. Each of Hipper’s shells weighed more than a man. Roope’s little destroyer might as well have been a tin toy.

Three hours earlier, Glowworm had been alone in heavy seas north of Norway. She was supposed to be screening the battlecruiser Renown, part of the Royal Navy force shadowing German moves along the coast. A man had gone overboard two days before in a gale. Roope had spent eighteen hours searching in thirty-foot swells, found nothing, and finally been forced to abandon the search. The crew was exhausted. Glowworm had fallen behind Renown in the storm and was now running hard to catch up.

At 08:00, a lookout had spotted smoke. Two German destroyers: Z11 Bernd von Arnim and Z18 Hans Lüdemann. They were full of troops, part of the first wave of Operation Weserübung—the German invasion of Norway—heading for Trondheim. Roope had stumbled into it blind.

Glowworm opened fire at 8,000 yards. The German destroyers returned fire, then turned north and ran. Roope knew the game. They were leading him toward something bigger. He knew it, and he chased anyway. If German heavy units were at sea, the Admiralty needed to know.

He sent a contact report and pressed the engines for all they could give in a sea that wanted to roll the ship over. Thirty-foot gray mountains slammed the bow. Glowworm rolled so hard men were thrown against bulkheads. Two more sailors went overboard and were lost. The gyro compass failed in the violence. The ship was back to steering by magnetic compass in a snow squall.

At 09:50, the fog lifted for maybe thirty seconds.

Admiral Hipper was there, less than 10,000 yards off the bow, huge and modern and deadly. One of Germany’s newest heavy cruisers, built to outrun anything she couldn’t outgun and outgun anything she couldn’t outrun.

There was no surprise for long. Hipper’s lookouts saw Glowworm about the same time Glowworm’s saw Hipper. Range closed. The German cruiser began to turn to unmask her full broadside.

Glowworm’s little guns barked first, more from reflex than effect. The first 4.7-inch salvo splashed short and wide. When Hipper answered, it was like a god had decided to throw anvils.

The first 8-inch salvo landed over. The second straddled. The fourth hit.

Shells crashed into Glowworm’s forward superstructure. One hit the director control tower and flooded it. Another wiped out the forward 4.7-inch gun. The radio room vanished. The mast came down and shorted the electrical system. Somewhere in the tangle, a siren circuit closed and stuck. Glowworm’s air raid siren started wailing and would not stop.

Roope ordered smoke and turned into it, disappearing into his own black cloud. That bought him maybe ninety seconds. It wasn’t enough to save the ship. It might be enough to buy a chance to strike back.

He had one weapon that could hurt a cruiser: ten torpedoes in two quintuple mounts. They were brand new models. Glowworm had been the test ship for the Royal Navy’s newest destroyer tubes.

He ordered them all made ready.

When Glowworm emerged from her own smoke, Hipper was waiting.

Range: 800 yards.

Point-blank for ships of that size. Close enough to see men moving on the German decks. Close enough that Hipper’s captain could watch Glowworm’s bow lift on the swells.

Hipper’s secondary battery—twenty 4.1-inch guns—opened up. The fire was surgical. Shells walked across Glowworm’s hull from bow to stern. The engine room took hits. Steam pressure faltered. Speed bled away. Men died in places Roope would never see.

He fired anyway.

All ten torpedoes ripped out of their tubes at 400 yards. From Glowworm’s bridge they could watch the white wakes streak toward the massive gray slab of Hipper’s side. For a few seconds, it seemed impossible they could miss. One passed so close ahead of Hipper’s bow that German sailors could probably have leaned over the rail and spit into its track.

The others all missed.

Hipper’s captain had put his rudder over at the last possible moment. Fourteen thousand tons of steel answered slowly, but it answered. Every single torpedo ran clear.

Glowworm had spent her sting.

The destroyer had three guns left in action. Hipper had twenty secondaries and eight main guns. The bridge was wrecked. The radio was gone. The engine room was flooding. The siren wailed over everything.

Roope’s options were gone too.

He could try to run, show his stern and hope the seas and smoke and luck conspired to hide him. He could strike his colors and pray a German boarding party arrived before the next 8-inch salvo. Or he could take the oldest option in naval combat, one no modern handbook considered anything but madness.

He could ram.

He didn’t hesitate long.

He ordered hard right rudder and opened the throttles. Glowworm’s bow swung toward the towering gray wall of the cruiser’s starboard side just abaft the anchor.

Hipper’s captain, Kapitän zur See Helmut Heye, saw what was happening a second too late. He ordered his own helm put over, trying to swing his ship to ram first. But turning a fourteen-thousand-ton ship is like turning a building. Even at twenty knots, momentum obeys its own schedule. Glowworm, half his size and far more nimble, answered her helm faster.

The range collapsed.

Glowworm’s siren howled. Her remaining guns spat uselessly. Her bow plowed through the green-gray sea as she lunged.

At 10:13, Glowworm hit.

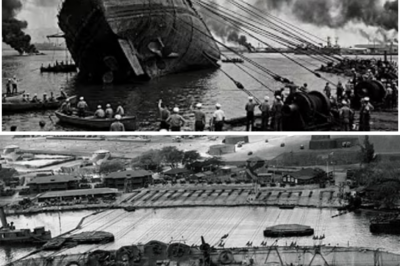

Her bow smashed into Hipper’s armored belt and crumpled like tinfoil. Steel folded back along her own hull, buckling frames, snapping lines. But inertia carried the 1,300-ton destroyer forward. She ground along the cruiser’s side in a shower of sparks and shrieking metal, ripping away armor plate like the skin off an orange.

For a hundred feet, Glowworm’s ruined bow carved open Hipper’s flank. An entire starboard torpedo mount crumpled and tore loose. Two huge holes opened up below the waterline. One German sailor working near the mount was swept overboard by the impact and vanished between the hulls. Compartments flooded instantly. Half a thousand tons of seawater poured in before Heye’s damage-control teams slammed doors shut and got pumps going. Freshwater tanks ruptured too—boiler feed, drinking water—gone.

From Glowworm, it probably looked like nothing. The destroyer bounced off and staggered clear.

From Hipper’s bridge, it looked like a nightmare. The cruiser took a list to starboard. Not fatal, not yet, but heavy enough to make everyone on board feel it in their boots.

Glowworm had bought her enemy three minutes of terror and ninety days in dry dock.

She didn’t have three minutes left.

Her bow was gone. Just twisted metal and ragged compartments open to the sea. She was taking on water fast. Her engines labored. Her stern gun crew, led by Petty Officer Walter Scott, kept firing as the destroyer limped past Hipper’s stern. They put three more 4.7-inch shells into the cruiser’s upper works at ranges so close Scott could see paint peeling where his rounds hit.

Hipper’s secondary battery replied.

Twenty guns at four hundred yards. They could not miss.

Shells tore Glowworm from stern to midships. The aft gun went silent. The engine room took another hit. Steam pressure died. The propellers stopped turning. Fire bloomed amidships. Somewhere below deck, the boilers burst their seams and seawater poured in.

At 10:17, Roope gave the order.

“Abandon ship.”

There were no boats to speak of, no calm water to lower them into even if there had been time. Men jumped from the listing hulk into a Norwegian Sea just a few degrees above freezing. Thirty-foot swells tossed men under and over again. They wore lifejackets, but in that water, life expectancy was measured in minutes.

Glowworm rolled, steadied, then rolled again.

Roope moved among the men on deck, helping them with life jackets, shoving them over the high side where the swells wouldn’t smash them against the hull. The siren still wailed. The deck was slick with fuel oil and seawater.

At 10:24, the end came.

The destroyer heeled hard to port. The remaining torpedo tubes went under. Hatches broke their seals. Water roared in. The boilers exploded with a sound like the sky cracking. Glowworm broke in two. The forward wreckage went under immediately. The stern hung vertically for a few seconds, men still clinging to it, tiny dark shapes against gray steel. Then it slid down into the green, taking 118 men with it.

Thirty-one men remained alive in the water, burnt, half-numb, choking on oil.

Heye had a choice too.

He could order Admiral Hipper to clear the area, leave the survivors to the sea. His ship was damaged. British heavy units were somewhere over the horizon. He was in a combat zone in the middle of an invasion.

He ordered “Stop engines” instead.

He brought his cruiser around and let her drift so the survivors would drift toward her hull. German sailors lined the rail, throwing lines and nets down, hauling freezing men out of the oil and swell. Soldiers from the invasion force joined them. They grabbed arm and wrist and tunic, heaved British sailors over the side, dragged them onto the deck, wrapped them in blankets.

Roope was in the water with his men, still helping, still pushing others toward ropes when they came within reach.

Someone on Hipper threw him a line. He grabbed it. They hauled him halfway up the cruiser’s steel side. His hands simply opened. There was nothing left in him to hold.

He fell back into the sea and was gone.

Thirty-one men from Glowworm made it onto Hipper. Only one was an officer, Lieutenant Robert Ramsay. Hy had them taken below, fed them, given them dry clothing. Then he sat down in his cabin and did something no German officer was required to do.

He wrote a letter.

He described the action in detail—the engagement, the torpedo attack, the ramming. He wrote that in his view, Lieutenant Commander Roope had displayed “the highest courage in accordance with the best traditions of the British Navy,” and that in his professional judgment, Roope deserved the Victoria Cross.

He gave the letter to the International Red Cross.

It would take five years to reach London.

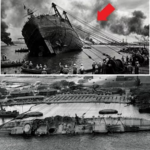

Admiral Hipper limped into Trondheim twelve hours after the collision, her damage camouflaged by distance and fresh paint. From the pier, she looked battered but serviceable. The forward starboard plating was gone along a hundred feet of hull. The torpedo mount was a twisted wreck. Emergency patches covered the worst of the openings. The cruiser could float. She could even move under her own power.

What she couldn’t do was fight.

When Hipper reached Wilhelmshaven and went into dry dock, shipyard engineers took one look at the exposed frames and realized what that single destroyer had done. Glowworm’s steel had not just scraped armor away. It had bent Hipper’s bones. Internal frames were buckled across forty feet. Bulkheads showed stress fractures. The keel itself had a visible twist. The forward freshwater tanks were ruptured. The structural damage meant she needed a full structural rebuild, not a quick patch.

She went into dock on April 20th. She came out in July.

In those three months, Norway fell. British and French convoys that Hipper was supposed to raid crossed the North Sea unmolested. Heavy surface raiders that she was supposed to screen operated without her. The German Navy’s margin for error, already razor thin, shrank further.

One British destroyer alone in a snow squall north of Norway had taken a heavy cruiser out of the war at the moment the Kriegsmarine needed her most.

Nobody in Britain knew.

Admiralty records for April 8th, 1940, showed a brief contact report from Glowworm at 09:58: two German destroyers sighted, later a heavy cruiser—likely Hipper. Then silence. The destroyer’s loss was chalked up as “sunk by enemy action while outnumbered.” A line on a report. A letter to a widow with the words “missing, presumed killed.” A ship name moved from the active list to the lost list.

Faith Roope spent five years not knowing how her husband died.

Lieutenant Ramsay and the thirty enlisted survivors spent those same five years behind barbed wire in German prison camps. They knew what had happened on the bridge and in the water. They did not know if anyone else ever would.

They came home in 1945.

Ramsay told the Admiralty the story. The survivors told it too. It was one story in a flood of stories from men who’d survived the Atlantic, the Arctic, Crete, Tobruk, Singapore, Dunkirk. Everyone had a story, and every story asked for recognition.

Glowworm’s sat in a file.

Then, in October of that year, the letter from Helmut Heye finally arrived.

Stamped and routed through Geneva and Lisbon and Madrid and a half-dozen wartime bureaucracies, it had taken five years to travel a few hundred miles of peacetime cable. It said what Ramsay and the others had said, but in a German hand, on Kriegsmarine stationery, from the captain of the very ship Glowworm had rammed.

That changed everything.

On July 6th, 1945, the London Gazette published an announcement. Lieutenant Commander Gerard Broadmead Roope, Royal Navy, was to be awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty” while in command of HMS Glowworm during action against superior enemy forces off Norway on April 8th, 1940.

The citation was spare and formal. It didn’t talk about the siren that wouldn’t stop or the thirty-foot seas or the oil-slicked water swallowing hands that slipped off ropes. It said he’d engaged enemy destroyers, followed them to a heavy cruiser, signaled contact, attacked, fought until his ship was shattered, then rammed the enemy with cool deliberation. It said he went down with his ship.

It didn’t say his enemy had asked that he be honored.

Faith Roope walked up the steps of Buckingham Palace in February 1946 to receive the bronze cross on a crimson ribbon from King George VI. She kept it the rest of her life. When she died in 2001, it passed into private hands. It’s not in a public case. You can’t walk into a museum and see it.

You can, however, stand on a windswept rock in Norway and read his name.

Four miles southwest of the tiny island of Gåsa, HMS Glowworm lies in 240 meters of cold water, declared a war grave by Norway in 1995. In 2024, a granite memorial went up on the island’s southern shore, facing the coordinates of the wreck. It carries 149 names.

The Royal Navy never named another ship Glowworm.

Destroyer captains still study Roope’s action. They debate whether ramming was tactically correct or simply courageous madness. They argue what they would have done facing a heavy cruiser with no torpedoes left and a wrecked ship beneath them. They all know what he did.

Modern ships fight at ranges where no one sees the whites of anyone’s eyes. Missiles launch beyond the horizon. Radars whisper threat vectors. Computers recommend solutions. There is no siren that gets stuck on, no chance to taste salt spray on your teeth as your bow lifts toward steel.

But someday, somewhere, some commanding officer will find himself with a broken ship and bad choices, with doctrine that no longer fits the moment and lives that hang on a decision no manual covers.

When he makes that decision, there’s a decent chance he’ll have seen a slide, or read a case study, or heard an instructor say, “There was a destroyer once, north of Norway…”

There was.

In heavy seas, in a snowstorm, with the enemy’s guns walking toward him, Lieutenant Commander Gerard Roope pointed a small, outgunned ship at a big, dangerous one and chose to hit something that could hit back. He didn’t live to see what that hit accomplished. He didn’t know about three months in dry dock or missed convoys or altered campaign plans. He only knew there was one thing left he could do.

He did it.

That’s why a German captain wrote a letter. That’s why a king pinned a cross. That’s why, more than eighty years later, a name on a stone on a Norwegian island still means something.

Because sometimes the only thing you can put between your enemy and the people behind you is your own hull. And sometimes, against all the math, all the doctrine, all the odds, that’s enough.

News

CH1 “The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming”

The searchlights swept the black water like fingers. Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse…

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

CH1 They Mocked His “Medieval” Airfield Trap — Until It Downed 6 Fighters Before They Even Took Off

The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42. Then another. Then four more in rapid succession. Six RAF fighters…

Stepfather Beat Me For Refusing To Serve His Son I Left With $1—Now I’m Worth Millions

CHAPTER ONE THE HOUSE THAT LEARNED HOW TO PRETEND I’m Emma. I’m twenty-eight years old now, but this story begins…

My Son and His Wife Assaulted Me on Christmas Eve After I Confronted Her for Stealing My Money

The phone wouldn’t stop ringing. It lit up on the coffee table over and over, buzzing against the wood, Garrett’s…

CH1 ‘Selling Sunset’ Alum Christine Quinn Criticizes Erika Kirk’s Public Profile After Charlie Kirk’s Death

LOS ANGELES — Reality TV star and former Selling Sunset cast member Christine Quinn ignited fresh controversy this week after…

End of content

No more pages to load