March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, 400 miles south of Iceland.

Convoy HX229 plows through fifteen-foot swells—41 merchant ships, nine columns wide, carrying 140,000 tons of food, fuel, and steel toward a Britain that is starving one cargo hold at a time.

On the SS William Eustace, 28-year-old ship’s cook Thomas “Tommy” Lawson washes dishes in a galley that won’t stop trying to throw him into the bulkhead. Grease slides across the stove. Cups smash. The ship rolls so hard the deck feels alive.

Above him on the bridge, Captain James Bannerman scans the horizon with binoculars and the quiet dread of a man who has learned a cruel truth:

The U-boats don’t need to see you to kill you.

Six hundred yards off the convoy’s port beam, deep enough to hide from the surface and shallow enough to listen, U-758 runs silent. Kapitänleutnant Helmut Mansack sits under red light in the control room, cigarette smoke trapped in stale air. His hydrophone operator presses headphones to his ears and whispers what Mansack has been waiting for all night.

“Kontakt… Peilung 280.”

Multiple screws. Heavy machinery hum. The slow, steady heartbeat of dozens of ships.

Mansack smiles.

Wolfpack has the convoy.

What none of them know—not Bannerman, not Mansack, not the escort commanders sweating over charts—is that a cook down below has noticed something strange about the way Liberty ships sound underwater.

And in less than a month, that observation will help break the back of Germany’s greatest weapon in the Atlantic.

The month Britain almost lost the war

March 1943 was the apex of the U-boat crisis.

The numbers were not dramatic. They were mathematical, which was worse.

567,000 tons of Allied shipping sunk in one month—more than any previous month of the war.

22 ships from HX229 and SC122 alone, in six days.

300 merchant seamen swallowed by black water.

Churchill later wrote the only thing that truly frightened him during the war was the U-boat peril, because it wasn’t about heroism or tactics.

It was about a ledger.

Britain imported two-thirds of its food and essentially all of its petroleum by sea. Lose enough ships, fast enough, and the war ends—quietly, not with surrender ceremonies, but with empty shelves and grounded aircraft and a nation collapsing under arithmetic.

German hydrophones were brutally effective because the Atlantic is an amplifier. Sound carries forever in cold water. A convoy didn’t just move.

It broadcast.

Propellers cavitated—tiny bubbles forming and collapsing with a crackle that traveled for miles. Engines vibrated. Shafts resonated. Hulls hummed like tuning forks. In ideal conditions, U-boats could pick up the “multiple screws” signature from extreme distance, then vector wolfpacks into firing position without transmitting a word.

Allied escort commanders tried everything:

Zigzagging (slower = longer exposure)

Radio silence (U-boats didn’t need your radio)

ASDIC sweeps (great forward cone; useless on a submarine attacking from astern)

More escorts (you can’t escort what you can’t find)

By early 1943, the expert consensus was grim: you can’t make a merchant ship quiet. Not without redesigning propulsion and hull forms—impossible in wartime mass production.

And then, in the middle of that failure, there was Tommy Lawson.

The cook who listened to engines

Lawson wasn’t a scientist. He barely finished school.

Born in South Boston in 1915, he dropped out at fourteen during the Depression and spent a decade in diners and on coastal freighters—grease under his nails, burned forearms, a life measured in shifts and tips.

He joined the Merchant Marine because it paid triple what he could earn back home, and because in 1943 the Merchant Marine was a frontline service whether you wore a uniform or not.

His captain’s evaluation described him as “adequate… no leadership potential… galley duties only.”

Nobody expects genius from the man who makes breakfast.

But Lawson had a habit that made the engineers laugh.

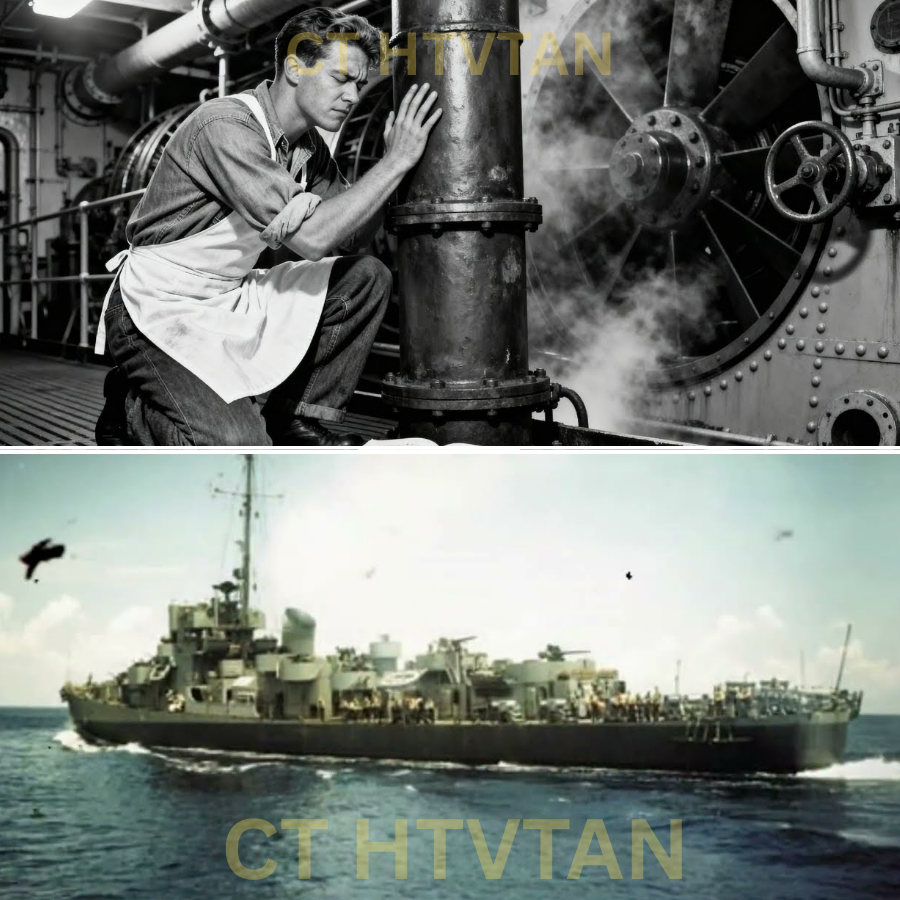

During off-watch, he sat in the engine room.

Not because it was comfortable—it was a metal furnace, loud enough to rattle teeth—but because he was trying to understand something he couldn’t name yet.

He listened the way cooks listen to an oven and know when it’s wrong. The way mechanics listen to a belt and hear failure before it snaps.

He listened to the ship.

And on February 19th, 1943, in convoy SC-118, he heard something that didn’t fit.

A ship in the column took a torpedo hit. Everybody onboard the Eustace felt the concussion through the hull like a fist in the chest. Men ran. Sirens screamed. And then, through the bulkheads, Lawson heard the part no one talked about:

Not the explosion.

What came after.

The sound changed.

The wounded ship began making a hollow booming—water rushing where air used to be—then the machinery note vanished like a blown-out candle.

The ship, dying, had gone acoustically quiet.

Lawson grabbed the ship’s engineer, a gruff Scotsman named Donald McLeod, and tried to explain it between engine roars.

“When it flooded,” Lawson shouted, “it stopped broadcasting. The vibration died.”

McLeod stared at him like he’d gone insane.

“So what, Cook?”

Lawson swallowed, then said the sentence that would get him laughed out of any Navy boardroom:

“What if we flood parts of our ship on purpose?”

Not enough to sink.

Just enough to silence—to dampen vibration where it turned into underwater sound.

McLeod’s response was immediate and profane.

“Get back to your bloody galley.”

But Lawson couldn’t let it go.

Because once you notice a pattern, you can’t unsee it.

For two weeks, he sketched diagrams in a notebook: sealed chambers around shaft housings, water-filled barriers against machinery mounts, controlled ballast—liquid insulation.

He showed the sketches to anyone who would look.

They didn’t.

Liverpool: the idea that got him arrested

March 24th, 1943. Liverpool.

The William Eustace makes port. The crew gets forty-eight hours of leave. Most men hunt beer and warmth and a bed that doesn’t move.

Tommy Lawson walks into Western Approaches Command headquarters at Derby House and asks to speak to an admiral about U-boat detection.

He doesn’t get an admiral.

He gets grabbed by shore patrol.

“This is a restricted facility, mate.”

Lawson tries to explain—convoy noise, hydrophones, flooding insulation—and the guards start dragging him out like a nuisance.

Then a voice cuts across the lobby.

“Wait.”

Commander Peter Gretton. Twenty-nine years old. Escort group commander. Just came off a run where he watched ships burn and men freeze to death in lifeboats.

He’s exhausted enough to listen to anything that isn’t doctrine.

“What did you say about convoy noise?”

Lawson explains it in plain language. The sinking ship going quiet. Water absorbing vibration. Hydrophones losing the signature.

Gretton’s first reaction is honest.

“That is the most ridiculous thing I’ve heard this month.”

Then he pauses—because ridiculous isn’t the same thing as wrong.

“Come with me.”

The illegal test nobody was supposed to run

March 25th. HM Dockyard, Liverpool.

Gretton takes Lawson to HMS Sunflower, a corvette in dry dock. If this is insanity, they’ll keep it small. Quiet. Unofficial.

Over three days, with the ship’s engineer Lieutenant James Whitby, they bolt and weld crude prototypes:

sealed steel drums around shaft housings

water-filled bladders pressed against machinery mounts

sandbags as ballast

It looks like plumbing in a warship. It violates regulations. It should get people court-martialed.

March 28th: first test.

A friendly submarine, HMS Trespasser, submerges 500 yards away and listens.

Result: failure. Hydrophones still hear Sunflower clearly.

Whitby smirks. “Told you.”

Then Lawson notices the killer detail: the drums are leaking. They weren’t full.

“We need to seal them. Make them watertight.”

Gretton runs a hand through his hair, staring at the line between stupidity and salvation.

“If Admiralty finds out, I’m finished.”

Lawson’s voice is quiet, exhausted, deadly serious.

“If we don’t solve this, we lose the war.”

Three more days.

They weld proper chambers. Tight seals. True water mass. Real contact surfaces.

April 2nd: second test.

Sunflower motors at speed. Trespasser listens from 1,000 yards.

Minutes pass.

Nothing.

The submarine surfaces and signals:

“Lost you at four hundred yards. Hydrophones got ocean—no ship.”

Gretton goes pale.

They didn’t just reduce noise.

They shattered the assumption that a ship must be heard from miles away.

The boardroom where a cook breaks physics

April 3rd. London.

Gretton drags Lawson into an Admiralty meeting and throws the test results on the table. Senior officers stare like it’s heresy.

Dr. Harold Burrus, chief naval architect, calls it impossible. Water means weight. Stability issues. Corrosion. “You’re basing doctrine on a cook.”

Gretton snaps back.

“A cook who’s doing better than your department while we sink.”

Admiral Max Horton, the Western Approaches commander, doesn’t care who thought of it.

He cares what it does.

He looks at Lawson.

“Explain it simply.”

Lawson, suddenly aware he’s a merchant seaman in cheap clothes addressing the men who decide whether Britain lives, says the only thing he knows:

“Machinery vibrates. Vibration travels into the hull. Into the water. Water absorbs vibration better than air. If you put sealed water mass against the right structures, you keep sound from reaching the ocean.”

Silence.

Then Horton asks the question that matters:

“What would it take to test it in convoy?”

Burrus says fleetwide retrofit is impossible. Years. Steel shortages. Dry dock congestion.

Lawson says something that terrifies experts, because it’s practical.

“It doesn’t take months. It took us days. You don’t retrofit everything. You retrofit enough to learn.”

Horton makes the kind of decision wars are won on:

“Six ships. One convoy. Eight days.”

If it works, they scale.

If it fails, Gretton gets banished to irrelevance.

And if it works?

The Atlantic changes shape.

The first convoy where ships disappear

Convoy ONS-184 departs Liverpool with 43 merchant ships. Six of them carry Lawson’s crude, ugly, water-filled dampening system.

U-boats find the convoy anyway—because the other thirty-seven ships are still loud as hell.

They attack. It’s brutal. Ships sink. Men die.

But something new happens in the hydrophone logs.

German operators report “intermittent” contact. Ships that vanish from sound. Targets that appear too late. Confusion in the tracking picture.

The wolfpack can still hunt the loud ones.

But the quiet ones slip through.

And that’s the tipping point.

Because wolfpack tactics require predictability.

If a convoy becomes acoustically patchy, the Germans lose their greatest advantage: long-range detection and coordinated approach.

Now U-boats have to get close.

And close means radar. Close means ASDIC. Close means escorts actually finding them.

Close means U-boats stop being hunters.

And start being prey.

Why the Allies tried to bury the story

Because it’s embarrassing.

Not for Lawson—for the experts.

In 1943, the Royal Navy and Allied research commands had spent fortunes chasing sophisticated fixes: rubber coatings, mount isolation, propeller redesigns, hull science.

And a cook walked in and said:

“Water absorbs vibration. Put water where the vibration is.”

It wasn’t magic.

It was attention.

It was noticing the moment a sinking ship went quiet and asking the forbidden question: what if we imitate that on purpose?

If your entire system runs on the belief that solutions come from people with titles, then a cook solving a strategic crisis isn’t just unlikely.

It’s threatening.

So the paperwork minimized him. The memos credited “field trials.” The official reports emphasized engineering teams. Lawson got a quiet medal, no headlines, no parade.

And then he went back to Boston and fried eggs for working men while the Atlantic stopped bleeding.

News

CH1 Tatiana Schlossberg’s Quiet $1 Million Gift to The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society: A Final Act of Love and Hope in Silence Before Her Passing

In the final months of her courageous battle with acute myeloid leukemia, Tatiana Schlossberg quietly made a profound decision that…

CH1 Meghan Markle “Caught” at LAX with Multiple Suitcases Full of Cash: K-9 Dogs Alert Sparks Frenzy Over Missing $12 Million from Prince Harry’s Account

Recently, Chaos erupted at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) when Meghan Markle was reportedly detained for questioning after K-9 sniffer…

CH1 How One Loader’s “STUPID” Ammo Swap Made Shermans Fire Twice as Fast

At exactly 08:47 hours on June 14th, 1944—three miles west of Carentan, Normandy—a Sherman tank sat motionless behind the collapsed…

CH1 How One Radio Operator’s “Forbidden” German Impersonation Saved 300 Men From Annihilation.

At 02:16 in the morning on December 19th, 1944, Corporal Eddie Voss crouched in a frozen foxhole outside Bastogne with…

CH1 Albert Brooks Finally EXPOSES Rob Reiner After Decades of Silence.. (It’s WORSE Than We Thought!)

The Night Before: The Argument That Now Sits at the Center of the Reiner Case The first thing people got…

CH1 From Rejection to Revolution: The Welder Who Saved 50 Million Hours in WWII

March 6th, 1941. Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California. 05:18 hours. The first thing you notice under a submarine deck…

End of content

No more pages to load