August 1944. France.

The Allied breakout from Normandy has cracked the German front wide open, and for the first time in years the war feels like it might end fast.

Too fast.

General George Patton’s Third Army is surging east—thirty, forty, sometimes fifty miles in a day—moving like an armored flood through towns the Germans barely have time to abandon. It looks unstoppable on the map.

But maps don’t burn gasoline.

Every Sherman tank drinks fuel like a drowning man drinks air. Every infantry division needs hundreds of tons of supplies every day—ammo, rations, bandages, spare parts, engine blocks, track links, radio batteries, oil, and more fuel on top of the fuel.

And now the Allied advance has run into the one enemy no amount of courage can shoot.

Distance.

Cherbourg is still a wreck, ports are bottlenecked, Antwerp is a dream weeks away, and everything—every single bullet—has to come from the Normandy beaches over roads the Germans smashed to rubble as they retreated.

Three hundred and fifty miles of broken France.

Trucks, day and night.

And the math does not add up.

At Supreme Headquarters, logistics officers stare at charts like they’re reading a death certificate. Patton’s spearheads are literally running dry. Some tank battalions are immobilized—not by Tigers, not by mines—by empty tanks.

On August 21st, Colonel Frank Ross, Chief of Transportation, briefs Eisenhower.

“We’re losing twenty-three percent of supplies before they reach the front,” he says. “Accidents. Breakdowns. Air attacks. Convoy pileups. If Patton stops moving, the Germans dig in. If he keeps moving without supply, he collapses.”

Eisenhower stares at the map. He traces the red line toward the German border like he can will it closer.

“How long to fix this?” he asks.

Ross hesitates.

“Weeks. Maybe months. We’d have to redesign the entire convoy system, build maintenance depots, restructure routing.”

Eisenhower’s eyes harden.

“I need solutions in days, gentlemen. Not months.”

The meeting ends with no answers.

And ninety miles away, in the cab of a GMC Jimmy, a man with no rank worth mentioning is looking at the answer lying in smoking pieces on the roadside.

Technical Sergeant Raymond “Ray” Kowalski—thirty-four, long-haul trucker from Pittsburgh before the war—sits with a cigarette burning down between his fingers and watches eight trucks overturned and blackened along a narrow French road.

Eight trucks.

Eight loads.

Eight lifelines turned into ash because a Luftwaffe fighter found a convoy bunched up like cattle in a chute.

Kowalski has seen this six times in two weeks.

He’s watched the same pattern play out again and again: twenty trucks stacked on a road, nose-to-tail, crawling along at doctrine speed—twenty-five miles an hour, sixty yards spacing, “mutual support.”

Sounds good in a manual.

In real life it means this:

When the lead truck brakes, everything behind it stops.

No room to maneuver.

No room to scatter.

No room to breathe.

A convoy isn’t a supply line anymore.

It’s a target.

Kowalski exhales smoke and remembers something his dispatcher used to say back in Pittsburgh, hauling steel through mountain roads in snowstorms.

“Convoys are for show. Profit’s in the spacing.”

That line hits him like a slap.

Because he’s been seeing something no officer seems to notice.

When the depots are delayed—when trucks load at different times and drivers leave alone or in pairs instead of waiting for the full convoy—those independent trucks keep arriving.

Every single one.

No mass casualty runs.

No pileups.

No strafing disasters.

And the Luftwaffe?

It doesn’t chase them.

Because a single truck isn’t worth the fuel.

But twenty trucks at once?

That’s a feast.

Kowalski pulls out a battered notebook and starts doing what he’s done his whole life.

He runs the numbers.

Convoys: 23% losses.

Independent runs: under 3%.

Not theory.

Not gut feeling.

Observed reality.

On August 25th, he takes the notebook to his company commander, Captain Dennis Hayes.

“Sir,” he says, “I think I can cut losses by ninety percent.”

Hayes barely looks up.

“Kowalski, you’re a goddamn truck driver. Leave tactics to people who went to West Point.”

The rejection comes back officially in writing.

Proposal: Denied.

Reason: violates established convoy doctrine.

Unauthorized deviation will be court-martialed.

Kowalski reads it and laughs—not because it’s funny, but because it’s insane.

These men are lecturing him about trucks like trucks are chess pieces instead of machines with weight and braking distance and turning radius.

He tries again.

He goes up the chain. He finds a deputy operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel Burgess, a man who at least listens long enough to nod.

“Ray,” Burgess says, “I understand your logic. But what happens when a truck breaks down alone? No support. Driver stranded.”

Kowalski doesn’t flinch.

“Sir, what happens now when a truck breaks down in a convoy? It stops the trucks behind it. And when the Luftwaffe hits one convoy, they don’t get one truck. They get twenty.”

Burgess wants to believe him. You can see it in his eyes.

But he’s trapped in a different battlefield.

Paper.

Doctrine.

The fear of being wrong in writing.

So he shakes his head.

“Appreciate the initiative. But we do things this way for reasons.”

Even other drivers turn on Kowalski.

“You trying to get us killed one at a time?” one sergeant shouts at a briefing.

“At least in a convoy, we’ve got backup!”

Kowalski tries to explain.

Backup doesn’t matter if you’re all dead together.

But fear is louder than math.

Then the hammer comes down.

Colonel Ross himself writes across the top of Kowalski’s proposal:

DENIED.

Any driver operating outside convoy parameters will face court-martial.

That should have been the end of it.

Except someone else has been reading the reports.

Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith—Eisenhower’s chief of staff—hasn’t slept properly in weeks. Patton’s been forced to halt. The supply crisis is closing the war’s window like a steel trap.

Smith is the kind of officer who reads everything. Even the stuff staff officers dismiss as “enlisted noise.”

On August 30th, Smith walks into Ross’s office unannounced.

“This Kowalski,” he says, tapping the memo. “Why was this rejected?”

Ross launches into doctrine.

Smith cuts him off like a guillotine.

“I read the doctrine. I’m asking why we’re losing a quarter of our supplies following it.”

Ross tries again.

“Losses are within expected—”

Smith’s voice goes cold.

“Expected parameters. Patton’s entire army is immobilized because we’re accepting expected parameters.”

He points at the paper.

“Get me this sergeant.”

Two hours later, Kowalski is standing in a headquarters tent facing colonels who smell like soap and paperwork. He’s in oil-stained coveralls, hasn’t shaved, and is pretty sure this ends with him in a stockade.

Smith doesn’t waste a second.

“Sergeant. Explain your method. Assume I know nothing about trucking.”

Kowalski inhales, steadying himself.

“Sir, the Germans can’t hit what they can’t predict. Right now, we leave in big convoys at known times, on known routes, at known speeds. They don’t have to hunt—we deliver the target.”

He opens his notebook.

“If we load and dispatch continuously—no waiting for twenty trucks to assemble—if we stagger departures every few minutes, spread across hours, then the Luftwaffe can’t set up ambushes. They’d have to hunt one truck at a time.”

Ross interrupts.

“And breakdowns?”

Kowalski points to the paper.

“Breakdown in a convoy stops nineteen trucks. Breakdown alone stops one truck.”

“And ground threats?”

“Same reality either way. Bypassed Germans can hit one truck or twenty. But a convoy gives them twenty.”

Silence.

Smith studies the numbers.

Then he says the sentence that changes everything.

“Then we test it.”

Ross protests.

Smith doesn’t care.

“One week. Twenty trucks. Kowalski runs dispatch. If losses drop below ten percent, we implement it.”

Ross goes red.

“This is insanity.”

Smith looks at him.

“If this fails, I take responsibility. But if it works, and we didn’t try it, that failure is mine too.”

Smith turns to Kowalski.

“You’ve got your chance, Sergeant. Don’t waste it.”

September 1st, 1944.

Kowalski stands at the Allenson Supply Depot at dawn, watching twenty trucks roll in to load. This is his trial. His one shot.

Under the old system, all twenty trucks would sit for hours until the slowest load finished. Then they’d roll out together at noon, crawling like a parade.

Under Kowalski’s system?

The first truck finishes loading at 0600.

Kowalski points.

“You’re gone. Route Seven. Run what’s safe.”

The driver blinks.

“No convoy?”

Kowalski stares him down.

“No convoy.”

The second truck finishes at 0618.

“Go.”

Third at 0633.

“Go.”

Instead of one big departure, he sends twenty trucks out across five hours.

And then he breaks another sacred rule:

Speed.

“Run what’s safe,” he tells them. “If you can do forty, do forty. If you can do thirty, do thirty. Just don’t bunch.”

Transportation Corps observers stand nearby taking furious notes.

Violation. Violation. Violation.

And then the results start coming back.

The first truck hits Third Army dumps faster than convoy averages.

Then the second.

Then the third.

And the Luftwaffe?

It sees trucks.

But it doesn’t stop them.

Because a single truck is a bad trade.

Fuel for one target.

Ammunition for one target.

Risk of being jumped by Allied fighters.

Not worth it.

On day one, all twenty trucks make it.

Zero losses.

On day two, nineteen make it. One wreck—driver fatigue, single vehicle.

Not a pileup. Not a massacre.

Day three: full delivery again.

By day five, even the skeptics are staring at the ledger like it’s a miracle.

Loss rate drops from 23% to under 3%.

And supplies start reaching Patton again in the volume he needs to keep moving.

On September 7th, Smith signs the order:

All Red Ball Express operations will adopt staggered dispatch protocols.

It spreads like wildfire.

Depots stop “forming convoys” and start acting like arteries—continuous flow instead of clotted mass.

Trucks stop being a parade.

They become weather.

Everywhere. Unpredictable. Uncatchable.

German reports begin to change tone.

Not rage—fatigue.

A Luftwaffe squadron commander writes what every pilot is thinking:

“Individual interdiction is inefficient use of limited resources.”

In other words:

We can’t afford to hunt ghosts.

And that’s the moment the supply war flips.

Not because the Allies found more trucks.

Not because Cherbourg magically repaired itself overnight.

Because one trucker understood a truth war colleges missed:

Bunching creates vulnerability. Spacing creates resilience.

Kowalski gets a Bronze Star.

Then he goes home.

Back to Pittsburgh.

Back to hauling steel.

No fame. No parades.

Just a medal in a drawer and the knowledge that for a few weeks in France, his “crazy” idea kept the Allied advance alive.

And decades later, when modern logistics doctrine teaches dispersed movement, variable routes, unpredictable scheduling—when militaries and companies alike learn that the hardest system to attack is the one that never repeats the same pattern—

They’re still living inside the same insight Kowalski wrote in a notebook beside a burning convoy:

The enemy can’t kill what he can’t predict.

News

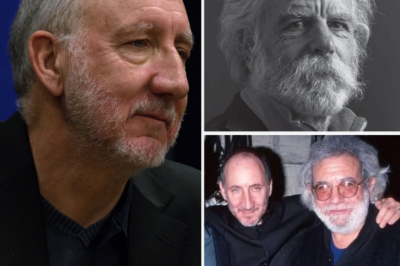

CH1 Pete Townshend Pays Tribute to Bob Weir

January 9th, 2026. The news hits like the first note of a song you never wanted to hear: Bob Weir is…

CH1 Harris Faulkner’s “Rebirth” Journey: Embracing Family, Love, and a New Chapter as Daughter Bella Heads to College

For weeks, fans have wondered why Emmy-winning Fox News anchor Harris Faulkner has been noticeably absent from Outnumbered and The…

CH1 Tatiana Schlossberg’s Quiet $1 Million Gift to The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society: A Final Act of Love and Hope in Silence Before Her Passing

In the final months of her courageous battle with acute myeloid leukemia, Tatiana Schlossberg quietly made a profound decision that…

CH1 Meghan Markle “Caught” at LAX with Multiple Suitcases Full of Cash: K-9 Dogs Alert Sparks Frenzy Over Missing $12 Million from Prince Harry’s Account

Recently, Chaos erupted at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) when Meghan Markle was reportedly detained for questioning after K-9 sniffer…

CH1 How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Stopped U-Boats From Detecting Convoys

March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, 400 miles south of Iceland. Convoy HX229 plows through fifteen-foot swells—41 merchant ships, nine columns…

CH1 How One Loader’s “STUPID” Ammo Swap Made Shermans Fire Twice as Fast

At exactly 08:47 hours on June 14th, 1944—three miles west of Carentan, Normandy—a Sherman tank sat motionless behind the collapsed…

End of content

No more pages to load