The searchlights swept the black water like fingers.

Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse of PT-219 and watched their white cones claw at the darkness off Vella Lavella. Somewhere out there, three Japanese destroyers were hunting him and eleven other plywood boats like his, sure they were chasing cornered prey.

They had no idea the prey had teeth.

PT-219 idled at six knots, twin Packard engines rumbling just above a whisper, exhaust muffled and vented through the transom into the sea. The boat rocked gently on the long South Pacific swell. The only light on board came from the hooded red glow over the chart table and the dim radiance from the instruments.

Sullivan raised his binoculars and watched the destroyers approach. Black hulks, low and lean, bow waves glowing faintly in the starlight. They moved with the big-ship arrogance he’d seen so many times since Guadalcanal—guns trained outboard, lookouts scanning lazily, captains convinced that nothing smaller than a cruiser could hurt them.

He smiled.

“Range?” he called.

“Twenty-two hundred yards and closing,” the quartermaster answered. “They’re coming in at twenty knots, Skipper.”

Sullivan dropped the glasses and glanced forward, where the bow looked like any other PT boat’s—low, uncluttered, nothing bigger than a .50-caliber mount in sight.

Underneath that deck, hidden from every Japanese eye and camera, sat a 40 mm Bofors gun waiting to rise.

The idea that put a cruiser-grade weapon on a plywood torpedo boat hadn’t come from a torpedo man. It hadn’t even come from a surface sailor.

It started six months earlier in a drafty warehouse office in San Diego, where Lieutenant Patricia Reynolds sat hunched over a metal desk, surrounded by stacks of after-action reports and a dead coffee pot.

Reynolds was one of the Navy’s first female ordnance engineers. That made her a curiosity in most rooms and an annoyance in some. She ignored both reactions. The numbers interested her more than people did.

She was reading translated excerpts from Japanese war diaries when she noticed the same phrase over and over again.

Mosquito attacks.

Japanese destroyer captains described PT boat raids with a mixture of irritation and contempt. The little American boats were fast and noisy, they wrote, their torpedoes occasionally deadly. But once the tubes were empty, the boats were harmless. “Machine-gun fire like insects,” one journal said. “Annoying but not serious.”

Reynolds pushed her glasses up her nose and circled the phrase. Harmless after torpedo expenditure. Japanese doctrine assumed PT boats carried only fish and light guns. That doctrine dictated their response.

Close them.

Destroyer captains were taught to charge PT boats head-on, relying on their armor to shrug off .50-caliber fire while bringing every secondary gun to bear. It made sense—until someone changed the equation.

She picked up a pencil and wrote in the margin.

If PT armament appears unchanged but delivers heavier firepower, tactical surprise guaranteed at close range.

She stared at the line, then reached for another folder. The Bofors 40 mm, developed in Sweden, built under license in America. Three tons of steel, four-shot clips feeding a gas-operated cannon that could fire 120 rounds per minute. Normally mounted on cruisers and destroyers for anti-aircraft defense.

What if—

She stopped and shook her head. On paper, it was ridiculous. The Bofors weighed as much as one of the Packard engines in a PT boat. The recoil would tear a wooden hull apart. The weight would drag the boat’s bow under.

But what if it didn’t?

She typed a memo and sent it up the chain: proposal to evaluate feasibility of mounting single 40 mm Bofors on Elco-type PT hull. She expected it to die somewhere above her pay grade, buried under more urgent projects like proximity fuses and aircraft rockets.

It didn’t.

Three weeks later, Commander Harrison Webb walked into the Higgins Industries yard in New Orleans with Reynolds’ memo in his briefcase and a knot in his stomach.

Webb was a career Annapolis man with grease under his nails. He’d spent more time in engine rooms than in wardrooms and had watched too many good PT boat crews die trying to sting destroyers with guns that couldn’t dent their hulls.

Andrew Jackson Higgins, the yard’s namesake, met him in his office in muddy work boots and a wrinkled shirt. Higgins had built his empire on two things: shallow-draft boats and stubbornness. When Webb explained what he wanted—a cruiser gun on a plywood torpedo boat—Higgins stared at him for a long moment.

Then he grinned.

“Hell, why not?” he said. “We’ve been putting guns on logs since this war started. Let’s see how far we can push it.”

They walked out into the bay where three green hulls sat on blocks, half finished. Welders’ torches sparked in the gloom. Sawdust and paint fumes mixed in the warm air.

“Weight’s your first problem,” Higgins said, knocking on one of the bare stringers. “You slap three tons on the bow and she’ll dig in like a hog. Recoil’s your second. Bofors kicks like a mule. Third is looks. You don’t want the Japs seeing it.”

“I need them to look like regular PTs,” Webb said. “From a mile away and from a thousand feet up.”

Higgins chewed his cigar and nodded. “We’ll hide it.”

His engineers went to work in a cordoned-off corner of the yard, under guard and behind tarps. They ripped out the bow framing of one test hull and rebuilt it with a lattice of steel beams tied back into the keel, distributing the expected recoil forces. They designed a hydraulic lift that could raise the Bofors mount through a deck hatch in under a minute and lower it flush again. On top of the hatch, they laid a cambered plank deck painted and scuffed to match the rest of the boat.

To anyone who didn’t know better, the bow looked like empty space.

To solve the weight problem, they swapped out nonessential equipment. The test boats would carry two torpedoes instead of four. They beefed up the Packard engines and experimented with propeller pitch until the modified boat actually gained a knot over standard.

They filled the fuel tank spaces with dummy weight and ran lake trials. Out on Lake Pontchartrain, with Webb and Higgins braced behind the cockpit, the experimental PT ran through its paces. It turned. It jumped onto a plane. It laid smoke. Finally Webb gave the order.

“Bring her up.”

Hydraulic pumps whined. The deck plate rose, split, and hinged back. A gray steel mount rose from the bow like something from a magician’s act. In twenty seconds the Bofors locked into place.

“Target buoy, 3,000 yards,” Webb said.

The gun crew—handpicked sailors from the Gulf Coast training flotilla who had signed extra security papers—slammed clips into the feed tray, swung the barrels, and fired.

The first burst rocked the boat. Recoil traveled through the reinforced bow and down the hull. Webb held his breath, waiting for something to crack.

Nothing did.

The water around the buoy erupted in white plumes. With each successive burst the gunner walked his shots onto the target. At 3,000 yards, the buoy disappeared.

“So far so good,” Higgins said around his cigar. “Let’s see if she stays together.”

They fired until their shoulders ached and their ears rang even through muffs. The hull held. The frames creaked, but that was it. Back at the yard, inspection showed no structural failures.

The Bofors PT worked.

Now they had to keep it secret.

The first dozen boats were completed in late July 1943. On paper they were PT-215 through PT-226, standard Elco 80-footers with “minor modifications to armament.” Their actual deck plans existed in only three places: Higgins Industries, Naval Ordnance in Washington, and a safe in Admiral Nimitz’s headquarters.

Even the skippers weren’t told until they reached the forward base.

Tulagi Harbor smelled like gasoline and mangroves. PT boats sat three deep along the piers, green hulls scarred by months of night fights around Guadalcanal. Oil drums, piles of depth charges, racks of torpedoes—all of it under a low gray ceiling of tropical cloud.

When Lieutenant Commander Marcus Sullivan arrived, he expected another plywood coffin.

He’d been in PT boats since ’42, running supply missions and torpedo attacks up the Slot. He’d watched Japanese destroyers run into torpedo spreads and blow apart. He’d also watched destroyers close to within a mile and turn PT boats into bonfires with a few well-placed shells.

The first time he stepped onto PT-219 at Tulagi, nothing told him this boat was different. Same three Packard engines. Same plywood hull. Same maze of lockers and bunks.

Then Chief Petty Officer Bill “Tank” Morrison took him forward, ducked under the low bow deck, and opened a narrow access hatch.

“Take a look, Skipper,” Morrison said.

Sullivan peered inside. In the dim light, the Bofors mount looked like some alien machine, all quadrants and gears and thick steel.

“What in God’s name is that, Tank?”

“Forty-millimeter Bofors, sir. Concealed mount. Hydraulic lift. Command says we’re not supposed to tell anybody at the bar.”

Sullivan grinned. “You think they’ll notice when we start knocking the hell out of destroyers?”

“Hard to keep that a secret, sir.”

Sullivan ran his hand along the cold barrel. He’d seen these guns on cruisers, hammering away at dive bombers. He’d never imagined standing this close to one on a eighty-foot boat.

“Can the hull take it?”

“Yes, sir. We tested her three nights straight. Shook the paint off the bulkheads, but the frames held. Packs’ll still push her forty-odd knots.”

Sullivan straightened.

“All right,” he said. “Let’s go pick a fight.”

It was one thing to shoot at a buoy in Louisiana. It was another to take four PTs with hidden Bofors out into Ironbottom Sound and trade blows with the Imperial Navy.

Their first chance came during the evacuation of Kolombangara at the end of August. Japanese destroyers had been pulling troops off the island in nightly runs, the famous “Tokyo Express.” PT boats had been harassing them for months, dodging searchlights, loosing torpedoes, and racing for cover while Japanese gunners filled the night with tracer.

Every boat in the Solomons had a story about seeing a destroyer at 3,000 yards and knowing there was nothing aboard that could harm her once the fish were gone.

On the night of August 27, 1943, Task Unit 73—four Bofors-equipped PTs under Sullivan—eased out of Tulagi and headed northwest. Their orders were simple: wait along the known route and hit anything that moved.

“Remember,” Sullivan told his skippers in the ready room that afternoon. “They don’t know what we’ve got. They think we’ve got torpedoes and popguns. Let ’em think it.”

“What about torps, Skipper?” one asked.

“We’re not taking any tonight.”

Heads had turned at that. No torpedoes on PT boats felt like sin. Sullivan shrugged.

“Extra weight, and we’ve got a better surprise. Our job isn’t to sink transports tonight. It’s to introduce a few tin cans to Swedish steel.”

They ran without lights, wakes glowing faintly in the bioluminescent water. The radio stayed mostly silent, just the occasional bearing check. Around midnight, their radar sets—recent gifts from the States—picked up three contacts: a destroyer formation with a transport in tow.

The Japanese saw them too. Lookouts spotted shadows ahead. On Hamakaze’s bridge, Captain Motoi Katsumi ordered general quarters and accelerated. His tactical manual told him exactly what to expect: a torpedo attack at three thousand yards, smoke, and a rapid retreat.

He turned to meet the threat.

Sullivan watched the green blips converge on his radar repeater. The destroyers were coming straight at them.

“Hold course,” he said. “Make like we’re lining up for a shot. All boats, maintain formation.”

The gap closed. At five thousand yards, Japanese searchlights snapped on, stabbing into the night.

“Now.”

Sullivan chopped the throttles to ten knots. His boat’s headway died. The destroyers, still charging, overshot the point where PT-boats usually turned away. Hamakaze’s gunners were waiting for torpedoes and a fleeing target.

What they got instead was seventy feet of plywood holding steady at fifteen hundred yards and a gun mount rising out of the bow.

“Bow ready,” Morrison called.

“Target: lead destroyer, bridge and fire control,” Sullivan said. “Commence firing.”

The first Bofors shell hit Hamakaze’s forward superstructure like a sledgehammer.

From Hamakaze’s bridge, it didn’t look like much at first—a bright flash on the port wing, sparks showering into the night. Then the concussion hit. The explosion ripped through the bridge canopy, shredded voice pipes, and turned rangefinders into twisted metal.

Three lookouts died without ever seeing the gun that killed them.

More flashes followed, climbing along the cruiser-gray shape of the destroyer. The Swedish gun’s rapid bark was almost lost against the thunder of Packard exhausts, but the effect was unmistakable. Where green tracer from .50-calibers used to splatter harmlessly against armor, heavy high-explosive rounds now punched through plating, detonated inside compartments, and blew doors off hinges.

On Yūgure’s bridge, Commander Sato Hiroshi stared in disbelief. PT boats did not do this. PT boats spat machine-gun bullets and screamed past.

These stayed.

He swore and ordered his main battery to engage, but his fire control radar was trying to track a target the size of a truck at ranges where it was designed to shoot cruisers. The solution smeared. Shells landed wide. PT-221 darted between the splashes, her own Bofors chattering flashes into Yūgure’s fire-control tower.

“Use their lights,” Sullivan shouted over the intercom. “They want to see us? Let ’em show us where to shoot.”

PT-223’s captain, Lieutenant Bob Chen, did exactly that. When Yūgure’s starboard searchlight lit his boat like a stage, his gun crew used the beam to find the source. Six rounds later, the light exploded in a shower of glass. The follow-up salvo walked shells down the destroyer’s forward deck, shredding her 25-mm mounts.

Shiranui, third in the column, tried to bring her guns to bear. Her captain swung the ship, exposing his broadside for better arcs of fire.

“Now’s your moment, Bob,” Sullivan muttered, watching on radar as Shiranui’s turn slowed her.

Chen was already moving. PT-223 poured on the power, angled across Shiranui’s stern, and at a thousand yards opened up with a full clip of Bofors into the destroyer’s engineering spaces. The 40 mm shells punched through plating at the waterline. Steam vented from ruptured lines. Shiranui’s speed dropped.

In less than a minute, three Japanese destroyers had taken damage they never expected from threats they never acknowledged.

On Hamakaze’s bridge, Katsumi had a choice to make. Torpedo the PTs and stand his ground, or withdraw and save what he could of his crippled formation.

The manual said to fight.

His instincts, honed by years of combat, said the manual had never anticipated this.

He chose life.

“Retreat,” he ordered. “Northwest. Maximum speed.”

Yūgure and Shiranui followed, their decks still burning, their crews reeling.

Sullivan watched their wakes turn away on radar. The transport they’d been escorting wallowed in their wake, abandoned.

“Pursue?” Morrison asked.

“No,” Sullivan said. “We’ve done enough for one night. Let the flyboys have that big fat pig in the morning.”

He stepped out from behind the armored bridge and walked forward to the Bofors mount, where the barrel still smoked in the night air. The gunners grinned at him, faces streaked black with cordite and sweat.

“Nice work, gentlemen,” he said. “We just rewrote the PT boat manual.”

Back at Tulagi, the debrief ran long.

Commander Webb read Sullivan’s report twice. The numbers were hard to believe. Four boats, no torpedoes, one sunk destroyer, two heavily damaged, all with a gun most officers still thought belonged only on larger hulls.

“Enemy responds to PT boat attacks based on assumptions about our armament that are no longer accurate,” Sullivan had written. “This provides opportunities for engagement under conditions where we possess decisive advantages.”

Webb smiled at the understatement. He wrote his own endorsement and sent it up the line.

Within weeks, Tanaka’s destroyer captains were seeing ghosts in every patch of phosphorescent wake. Reports came back to Rabaul describing “large-caliber weapons of unknown type” on American patrol craft. Japanese intelligence analysts scratched their heads. The only way they could reconcile the reports was to assume the Americans had built an entirely new class of gunboats—something between a PT boat and a destroyer.

They never guessed the guns were rising out of decks they’d already photographed a dozen times.

In Tokyo, staff officers updated tactical manuals. Avoid closing with PT boats in narrow waters. Use main battery at longer range. Do not assume enemy patrol craft are lightly armed.

On the chartboards in the Solomons, the effect showed up in a different color. Red lines—the routes of Japanese supply convoys—began to change. Some stopped altogether. “Tokyo Express” runs were rerouted away from known PT bases. Destroyers tasked with evacuation and resupply started sailing with more caution, longer delays, and greater fear.

On the chalkboard at Higgins’ yard in New Orleans, someone scratched a note next to the production schedule for PT hulls.

“Make room for more Bofors.”

The bow-gun PT experiment never became a numbered class. There were no fanfare-filled press releases, no glossy Bureau of Ships brochures. It remained what it had been born as: a field expedient, a weapon for a time and a place.

But in that time and place, off black islands lit by gun flashes, a handful of little boats with big guns punched well above their weight.

They gave PT crews something they had never really had before when facing destroyers: a fighting chance.

They gave ordnance officers a proof of concept: that the enemy’s assumptions were as valuable as any piece of equipment.

They gave a woman in a warehouse in San Diego, a boat builder in muddy boots, and a quiet ordnance commander the satisfaction of knowing that a line on a memo and a sketch in a manila folder had become real.

And they gave a destroyer captain named Motoi Katsumi something he never forgot. Months later, writing in his private journal after yet another night patrol where he chose caution over doctrine, he summed it up in one bitter sentence.

“We used to hunt their little boats like insects,” he wrote. “Now, when I see a shadow on the water, I am no longer sure who is hunting whom.”

The war rolled on. The Solomons campaign gave way to the Central Pacific push, to Marianas and Leyte and Okinawa. PT boats kept fighting, smoking, and torpedoing. Some carried Bofors, some didn’t. New weapons replaced old surprises. Radar grew sharper. Air power grew heavier.

But on the nights when the sea was calm and the engines were trimmed just right, you could still hear, under the steady thunder of three Packards, the faint hydraulic whine of a gun mount rising from a deck that looked, to every Japanese eye, completely harmless.

That sound meant the equation had changed.

That sound meant the hunters had become the hunted.

News

CH1 Joy Reid Reposts Viral Video Calling “Jingle Bells” Racist, Sparking Fresh Debate Over Christmas Classic

NEW YORK — Former MSNBC host Joy Reid reignited a familiar culture-war debate this week after reposting a viral video…

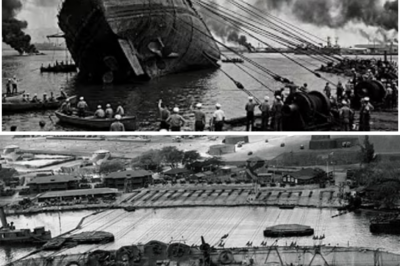

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

CH1 They Mocked His “Medieval” Airfield Trap — Until It Downed 6 Fighters Before They Even Took Off

The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42. Then another. Then four more in rapid succession. Six RAF fighters…

Stepfather Beat Me For Refusing To Serve His Son I Left With $1—Now I’m Worth Millions

CHAPTER ONE THE HOUSE THAT LEARNED HOW TO PRETEND I’m Emma. I’m twenty-eight years old now, but this story begins…

My Son and His Wife Assaulted Me on Christmas Eve After I Confronted Her for Stealing My Money

The phone wouldn’t stop ringing. It lit up on the coffee table over and over, buzzing against the wood, Garrett’s…

CH1 ‘Selling Sunset’ Alum Christine Quinn Criticizes Erika Kirk’s Public Profile After Charlie Kirk’s Death

LOS ANGELES — Reality TV star and former Selling Sunset cast member Christine Quinn ignited fresh controversy this week after…

End of content

No more pages to load