The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42.

Then another.

Then four more in rapid succession.

Six RAF fighters shattered before their wheels ever left the tarmac.

The Luftwaffe pilot banking overhead never fired a shot. He simply watched the chain reaction below, rolled his aircraft onto heading, and turned for home. On the ground, amid smoke, twisted aluminum, and sheets of burning canvas, one man stood exactly where he’d told everyone he would be.

Vindicated.

They had called his idea medieval. Obsolete. A waste of wire and engineering hours.

Spring 1940. The air war over Europe had become a mathematics problem no one seemed able to solve. German bombers crossed the Channel in formations so tight they blotted out patches of sky. Hurricanes and Spitfires scrambled upward, burning fuel and precious seconds just to reach combat altitude.

But it was the fighters on the ground that died most often.

Caught while taxiing. Destroyed as pilots sprinted toward cockpits. Annihilated in neat rows, wingtip to wingtip, before a single engine coughed to life. RAF Fighter Command called it the scramble problem. Radar gave warning. Observers telephoned coordinates. Air crews ran. Mechanics spun propellers.

The gap between alarm and altitude was a killing field measured in minutes.

Luftwaffe pilots learned to hunt inside that gap. They came in low, skimming hedgerows and treetops, strafing grass and asphalt, turning airfields into bonfires. Station commanders tried dispersal. They scattered aircraft across fields, hid them under camouflage nets, parked them in earthen revetments.

It helped.

It wasn’t enough.

Revetments took weeks to build and required earth-moving equipment most stations didn’t have. The Germans adapted faster. They sent fighter sweeps ahead of bomber streams, clearing the skies by clearing the runways first.

Engineers proposed solutions. Concrete shelters. Buried fuel lines. Faster startup procedures. All logical. All too slow. Construction crews could not outpace the Luftwaffe’s operational tempo. Every fix required resources Britain did not have and time the calendar would not grant.

Then a name surfaced in a maintenance log at RAF Kenley, a sector station south of London.

Flight Lieutenant Wilfred Truelove. Not a pilot. Not a tactician. A technical officer responsible for keeping machines airborne. His proposal reached group headquarters in a manila folder marked LOW PRIORITY. The summary was three paragraphs. The diagram looked like something from a siege engine manual.

Most officers read it once and set it aside. One called it “medieval” to his face. Another suggested Truelove stick to oil changes and tire pressure.

The sector commander at Kenley, though, had watched too many aircraft burn before breakfast. He gave Truelove seventy-two hours and whatever scrap materials the base could spare.

Wilfred Truelove had grown up in the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral, where his father repaired clocks—gears and springs, escapements and counterweights, the logic of energy stored and released. By fourteen, Wilfred could disassemble a watch movement blindfolded. By sixteen, he was apprenticing with an automotive engineer in Maidstone, learning how combustion engines translated fuel into motion.

He joined the RAF in 1936, not as aircrew but as a technical specialist. This new air force needed men who understood metal fatigue and hydraulic pressure, men who could read a schematic and turn it into a field repair with three tools and a length of wire.

Truelove was quiet, methodical. The sort of airman who noticed when a bolt was over-torqued or a fuel mixture ran too rich. At Kenley he became the officer pilots sought when something was wrong but the manual offered no answer. He could listen to an engine and diagnose a failing magneto. He could run his fingers along a control cable and know it would snap in two more sorties. His logbook was filled with marginal notes, sketches, and small innovations that never made it into official reports.

He wasn’t a theorist.

He simply watched.

And in the spring of 1940, what he watched was waste.

Aircraft destroyed not in combat, but in the first thirty seconds between ignition and takeoff. Pilots killed while still on the ground. Hurricanes flattened by cannon fire as their pilots scrambled across wet grass. Gun camera films from German fighters showed Spitfires exploding in rows, their canopies still open.

The calculus was brutal. Germany could replace bombers faster than Britain could replace fighters, and fighters died fastest when they could not fight back.

Truelove began spending evenings walking the perimeter of the airfield. He studied approach angles, noted terrain, watched how enemy aircraft came in along the treeline, low and fast, using the morning sun as cover. He asked the question his father had taught him years earlier in a cramped clock shop.

What stops motion most efficiently?

The answer was old. Older than aviation. Older than engines.

Tension and inertia.

A barrier that turns speed into catastrophe.

The Luftwaffe owned the initiative. That was the problem no doctrine could solve. German pilots chose when and where to strike. British pilots reacted. Reaction required time. Time required survival.

And survival in early 1940 was a matter of seconds.

Fighter Command tried everything. They stationed ground crews in blast shelters close to the flight line. They preflighted aircraft at dawn so pilots could scramble faster. They assigned mechanics to sleep in cockpits during high alert periods.

None of it changed the equation.

A Messerschmitt diving at 300 knots could close the distance from treeline to tarmac in under twenty seconds. A Hurricane needed ninety seconds just to taxi into position.

Engineers proposed active defenses. Anti-aircraft positions around the perimeter. Smoke generators to obscure the field. Decoy aircraft made of wood and canvas.

All were implemented.

All were insufficient.

AA guns could not track low-flying fighters weaving through their own flak. Smoke drifted with the wind and blinded friendly pilots as often as enemy ones. Decoys worked once, maybe twice, before reconnaissance photographs exposed them.

At a sector conference in late April, a group captain from Tangmere summarized the situation in eight flat words.

“We lose more aircraft on the ground than aloft.”

The room went silent. Everyone knew it was true. No one knew what to do about it.

Truelove wasn’t at the conference. He was at Kenley, drafting his proposal on the back of a maintenance checklist.

His idea was not elegant. It was not modern. It violated the aesthetics of aerial warfare.

It was grounded in physics older than flight.

He brought the drawing to his commanding officer on a Tuesday morning. The sector commander, Wing Commander Thomas Brickman, studied it for thirty seconds, then looked up.

“You’re serious, Wilfred?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You understand how it looks.”

“I do.”

The drawing showed a grid of steel cables stretched across the approach end of the airfield at precise intervals. Each cable anchored to buried concrete blocks and tensioned with automotive springs. Each cable normally lay flat, sunk in shallow slots, but could be raised to six feet in less than ten seconds by a system of pulleys operated from slit trenches at the field’s edge.

When enemy aircraft approached at strafing height, ground crew would yank the cables up.

Any fighter traveling at 250–300 knots that met that wire would not survive. Propeller blades would disintegrate. Landing gear would rip off. Wings would crumple. Fuel tanks would tear. The aircraft would tumble forward, turn into scrap and flame across the turf. The RAF didn’t have to shoot them.

They just had to wait.

Brickman frowned.

“And our own aircraft?”

“The cables lie flat during normal operations,” Truelove said. “Pilots taxi over them. They won’t know they’re there. Observers in the trenches raise them only when enemy aircraft approach. At this height and distance, sir, even a corporal distinguishing a Spitfire from a 109 can do it.”

He tapped the sketch.

“Speed is the enemy. We make it kill them.”

Brickman was skeptical, but he’d also walked among burnt fighters too many times. He gave Truelove three days and access to the motor pool.

Truelove recruited four mechanics and a welder. They scavenged steel cable from a bombed-out warehouse in Croydon, springs from wrecked lorries, concrete mix from a Public Works depot. They built anchors from old engine blocks and cast their own counterweights in empty oil drums. They did the wiring at night under blackout, headlamps hooded, hands numb.

By Thursday, the first cable ran across a disused section of the southern taxiway. Truelove tested the pulleys, watched the wire snap upward, measured the height with a stick, adjusted the spring tension, tested again. A small crowd gathered, mostly ground crew and a few curious pilots. No one believed it would work. No one stopped him either.

On Friday at 04:00, Truelove and his team finished installation. Sixteen cables stretched across the primary low-level approach path, each connected to a central pulley station concealed in a sandbagged trench thirty yards from the runway edge. The system weighed less than 800 pounds and had cost Fighter Command precisely nothing in materials. Everything was salvage.

At 05:30, the operations room received a radar plot. Unidentified aircraft inbound from the southeast. Low altitude, high speed. Estimated time to Kenley: eight minutes.

The scramble bell rang. Pilots ran. Engines coughed and roared. Truelove dropped into the cable trench with two ground crewmen and gripped the release lines.

“Wait for my call,” he told them.

The formation appeared first as dots, then as shapes—six Bf 109s in loose finger-four, skimming fifty feet above the fields, coming in along the treeline, just as he’d sketched.

The leader dipped a wing toward the runway. His cannon flashed. Tracers tore up the grass. Dirt geysered. Bullets stitched toward the parked Hurricanes.

“Now!” Truelove shouted.

They hauled on the lines with everything they had. Springs snapped taut. The cables leapt upward.

The lead Messerschmitt hit at about 280 knots. The wire caught his prop disk just below the hub. The impact ripped the blades off in a fraction of a second. Shards of metal scythed into the engine cowling. With its nose load gone, the fighter pitched forward like a poleaxed horse. It buried its snout in the turf and cartwheeled, shedding wings and tail and fuel in a tumbling arc that ended in a rolling ball of orange and black.

The second 109 hit 0.3 seconds later. This time the wire caught the leading edge of both wings. The impact tore them away. The fuselage continued alone for twenty yards then slammed into the ground, breaking in three.

The third pilot saw something—wreckage, a flash, instinct—and tried to pull up. Too late. His undercarriage caught the cable. The shock ripped the wheels off and flipped the aircraft inverted to slam into the grass at two hundred knots.

The fourth and fifth pilots saw the carnage and broke hard left, but the cable grid was wider than they realized. One clipped wire with his wingtip. The cable tore off his aileron. He rolled out of control and went in beyond the trees. The other clipped the tailplane, lost control authority, and spun into a hedgerow.

The sixth pilot yanked his stick and climbed, rolling away from the field. He made a single angry circle, saw five burning wrecks and a runway intact beneath them, and did the only sane thing left.

He went home.

It had taken eleven seconds.

Truelove and his crew dropped the cables. The siren still howled. Smoke drifted. A flight of Hurricanes taxied past the bent prop of the first 109, dodged a crater, and rolled onto the grass strip. One by one, they pulled back their throttles and clawed into the morning sky.

By noon, photographs of the wreckage were on the desks at Fighter Command. By evening, an engineering team from Farnborough was walking the crash sites with calipers and notebooks, interviewing the trench crews, tracing the cable runs.

On Sunday, Wilfred Truelove stood in a briefing room at Bentley Priory, headquarters of Fighter Command, facing Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding.

Dowding looked at the photographs. He looked at the diagrams. He listened to the explanation.

“How much does it cost?” he asked.

“Scrap, sir,” Truelove said. “Concrete, cable, springs. Whatever we can steal that isn’t nailed down.”

“How fast can it be installed?”

“Forty-eight hours on a flat field. Less if we cut corners.”

“How many aircraft has it saved?”

“Six, so far,” Truelove said. “Possibly more, if the Luftwaffe changes tactics.”

Dowding nodded once.

“Install it at every station that can use it. You’re in charge of the program now. Don’t waste time.”

Truelove saluted. He didn’t feel like a man who had just changed anything. He felt like a man who had too many airfields and not enough cable.

Within two weeks, variants of his barrier system were strung at Biggin Hill, Tangmere, Northolt, Manston, and other exposed stations in the south. Each field adapted the idea to its own geography. Some used natural drainage ditches to hide anchors. Some ran cables under removable planks. The materials remained scavenged. The cost remained essentially zero.

Luftwaffe pilots noticed.

Reconnaissance photos showed strange patterns across British runways—dark lines where there had been none before. After-action reports mentioned “wire traps” and “unexpected obstacles.” A few more low-level strafers died the way the first five had at Kenley. German planners issued new directives: no more ultra-low-level attacks on well-defended airfields. Fighters were to stay higher, attack from steeper angles, or leave airfields alone entirely.

That adjustment saved aircraft without a single extra gun.

At those fields with cable barriers, the number of fighters destroyed on the ground by strafing attacks dropped by around forty percent over the next month. It wasn’t magic. Bombs and high-level attacks still did damage. Hangars still burned. But the worst slaughter—the neat rows of fighters shredded at ten feet above the grass—became rarer.

The “Kenley wires,” as some pilots called them, were never standardized in a formal Air Ministry pamphlet. By late summer, the Luftwaffe had largely shifted from strafing to bombing. The Battle of Britain moved into its daylight phase. The urgent need for cable traps receded. Some stations dismantled them to extend runways. Others left them in place, rusting quietly in the turf.

The idea didn’t vanish entirely. Engineers in North Africa adapted the design for desert strips, stringing cables between oil drum anchors. Coastal Command experimented with similar principles to protect seaplane stations. American observers took notes. The concept of a cheap, passive barrier that exploited an attacker’s own speed lodged itself in a few engineering minds.

Official histories of Fighter Command mention the cable barrier in a single line, buried in an appendix. Fourteen words. No name.

Wilfred Truelove retired from the RAF in 1946 as a squadron leader. He went back to Canterbury, opened a small engineering shop near the cathedral, repaired farm machinery, built jigs and fixtures for local garages. He married, raised children, went to church on Sundays. If anyone in the pub asked what he’d done in the war, he said, “Kept aeroplanes flying,” and left it at that.

He died in 1983.

His obituary in the local paper mentioned his service, the rank he’d achieved, nothing more. After the funeral, his family went through his tools. In the bottom of a dented metal box under the workbench, they found graph paper folded in quarters. Pencil lines. Cable runs. Little circles where posts should go. Notations in a tidy hand: “Spring tension here,” “line of sight,” “enemy approach.”

They donated the drawings to the Imperial War Museum. The curator filed them in a folder labeled “Miscellaneous field modifications” and slid it into a drawer.

But the logic remained.

Truelove had understood something most strategists missed in those frantic months of 1940. Innovation isn’t always forward. Sometimes the answer to a modern problem lies in an ancient principle applied with ruthless precision.

Speed is a vulnerability as much as an asset if you can make it meet something that doesn’t move.

He didn’t reinvent warfare. He didn’t write doctrine. He just looked at the way Messerschmitts swooped on his airfield and asked the question his father had taught him in a Canterbury clock shop: how do you stop motion?

In a world obsessed with altitude, horsepower, and rate of climb, he dragged the fight back down to the grass and laid a wire across it.

There’s no monument at Kenley for Wilfred Truelove. The airfield is mostly gone, turned into housing estates and light industrial units. The cable trenches have been filled in. Children ride bicycles where his wires once lay.

Somewhere over the Channel, though, in the memory of an old Luftwaffe pilot who survived the war, there might still be a flash of wires where no wires should be and the sudden, sickening realization that the ground has just risen up to swat him out of the sky.

Medieval, they called it.

It worked.

News

CH1 Joy Reid Reposts Viral Video Calling “Jingle Bells” Racist, Sparking Fresh Debate Over Christmas Classic

NEW YORK — Former MSNBC host Joy Reid reignited a familiar culture-war debate this week after reposting a viral video…

CH1 “The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming”

The searchlights swept the black water like fingers. Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse…

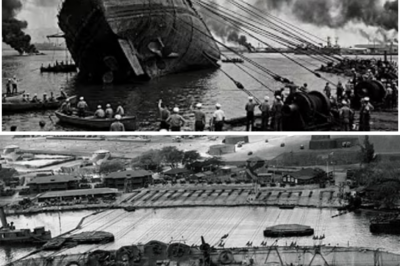

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

Stepfather Beat Me For Refusing To Serve His Son I Left With $1—Now I’m Worth Millions

CHAPTER ONE THE HOUSE THAT LEARNED HOW TO PRETEND I’m Emma. I’m twenty-eight years old now, but this story begins…

My Son and His Wife Assaulted Me on Christmas Eve After I Confronted Her for Stealing My Money

The phone wouldn’t stop ringing. It lit up on the coffee table over and over, buzzing against the wood, Garrett’s…

CH1 ‘Selling Sunset’ Alum Christine Quinn Criticizes Erika Kirk’s Public Profile After Charlie Kirk’s Death

LOS ANGELES — Reality TV star and former Selling Sunset cast member Christine Quinn ignited fresh controversy this week after…

End of content

No more pages to load