The night was so black it felt solid.

November 14th, 1942. 0320 hours. Ironbottom Sound, south of Guadalcanal. Admiral Willis A. Lee stood on the bridge of USS Washington, flagship of a task group groping through dark water toward an invisible fight.

Somewhere ahead, beyond rain and horizon, was the Japanese battleship Kirishima with her escorts. No moon, no searchlights, no silhouettes. To the naked eye there was nothing but wet wind and spray.

On the plotting table inside Washington’s flag plot, something else was moving.

A small green blip ran across the glass face of a brand-new device most of the Navy didn’t trust yet: the Mark 8 fire-control radar. Every sweep of its trace painted a range and a bearing where human eyes saw only void.

Washington’s 16-inch guns could throw a one-ton shell more than 20 miles. For a hundred years, battleships had lived by one rule: you only hit what you can see. Tonight, Lee was about to break that rule.

He hesitated.

The textbooks he’d written on gunnery—real textbooks, used by a generation of officers—said you waited for visual contact. You confirmed with optics. Radar, if you had it, was a secondary check. But down below the bridge, in the red glow of the plotting room, men hunched over the Ford Mark 1 mechanical computer. Gears, dials, and electric motors turned those radar numbers into firing solutions, correcting for roll, wind, target motion, muzzle velocity, even the Earth’s rotation.

Every few seconds a young officer called up to the bridge in a flat, clipped voice.

“Target bearing one-four-six. Range one-eight thousand. Course zero-two-three. Speed two-six knots.”

Lee studied the radar repeater. The echo was steady now. Not a ghost, not sea clutter, not rain. Something big and metal was out there, closing.

On any other night, he’d have waited for a smudge of smoke or a pale line of wake. Tonight there were no hints. Just a green pip and his own judgment.

“If it’s wrong,” he said quietly to his gunnery officer, “we’ll miss by miles. If it’s right, we’ll make history.”

He gave the order.

“All main batteries, load armor-piercing. Target bearing one-four-six, range two-zero thousand. Commence firing.”

Deep inside the armored hull, powder bags slid into place behind 2,700-pound shells. Breeches closed with a metallic slam. Men stepped back. The turret captains watched the last figures settle on their dials.

Washington’s first broadside shook the ship like a living thing. Nine 16-inch guns spoke together, the blast turning the sea alongside into a white, hammer-flat sheet. The flash lit the bridge in a brief, orange glare. Then darkness again, and the long wait for impact.

Thirty seconds later, the radar operator watched the sweep come around and saw something new: the return shifted, blooming, then dragging. He grabbed his sound-powered phone.

“Splashes on target,” he reported. “Looks like a hit.”

On the bridge, nobody cheered. Nobody had ever seen a hit reported from a radar screen before. For a heartbeat, Lee just listened to the silence outside and the hum of electronics inside.

“Range decreasing,” the plotting officer called up. “Target slowing.”

Lee nodded once.

“Repeat.”

The second salvo went out with small corrections from the Mark 1. Again, nine guns, again the concussion, again the waiting. This time the operator didn’t wait for the trace to come around.

“Multiple hits,” he said. “She’s really slowing now.”

Somewhere ahead, still invisible to every eye aboard Washington, Kirishima was taking blows she couldn’t answer. Her own optical rangefinders couldn’t find Washington through the driving squalls. Her gunners were still searching for muzzle flashes that never appeared. The American ship was firing blind and landing punches.

Men who’d grown up on optics felt the world tilt a little.

For centuries, naval gunnery had been a visual art. Admirals lived and died by what they could see from the bridge wings. Rangefinder operators learned to judge deflection by feel, elevation by horizon, hit patterns by spray.

Now, on a rainy November night, the center of Washington’s fight wasn’t on the bridge at all. It was two decks below, in a cramped compartment lit by red bulbs and a sickly green phosphor glow.

The Mark 8 radar was barely bigger than a desk. Inside its steel case, high-frequency pulses swung through a narrow beam, bounced off steel, and came home as tiny electrical whispers. Circuits translated those whispers into a single moving spot.

The Ford Mark 1 computer, bolted to the deck nearby, was a museum of gears. Hand wheels spun, cams rotated, shafts turned. Men fed it bearing, range, own-ship speed, target speed, wind. It answered with corrected gun orders.

It was crude by later standards. But that night, it was enough to bridge the oldest gap in naval warfare: the moment between not seeing and shooting anyway.

As Washington continued to fire, the echoes on the radar screen changed. Kirishima’s trace first slowed, then began to drift erratically. Smaller targets—destroyers and cruisers—twisted and scattered around her. Every American salvo complicated their lives. Their night optics were dazzled by their own gun flashes. Their training, built around visual contact, was useless against an enemy that might as well have been a ghost.

On the battleship South Dakota, limping nearby with her own electronics knocked out, sailors watched Washington’s gun flashes walking away into the dark. They had no idea what she was shooting at. They only knew that whatever was out there wasn’t shooting back as much anymore.

Kirishima tried to fight. Her secondary guns fired into the black. Torpedoes went into the water blind. It didn’t matter. Washington’s radar never blinked. Shell by shell, salvo by salvo, Lee’s battlewagon pounded an outline only his machines could see.

Shortly after 0420, the echo that had been Kirishima simply vanished.

“Target lost,” the radar man said. “Range zero.”

Lee let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding. Around him, men relaxed by inches. They had done something no one had ever done: killed a battleship they’d never seen.

The action report that Washington’s officers wrote later didn’t mention any of that. In dry language it read: “Enemy battleship engaged and sunk by radar-controlled fire at approximately 18,500 yards.” No mention of doubt. No mention of the moment when Lee chose phosphor over horizon. Just numbers.

But the men told each other the real story.

In the turret compartments, gun crews leaned against hot steel, smelling burned powder and oil, feeling the slight tremor of the ship. A loader ran his hand along the barrel and said, “We hit what we couldn’t see.”

“Guess we ain’t blind anymore,” someone answered.

Word filtered through the fleet. Captains from other ships came aboard at Espiritu Santo to look at Washington’s new “magic box.” The Mark 8 didn’t look like much—just a display, some knobs, the faint tick of its time base. It hummed and smelled like hot dust.

What mattered wasn’t the box itself. It was the chain it completed: radar input, mechanical brain, big guns.

From that night on, every serious American warship would have that chain.

Optical sights stayed as backup, but the center of gravity had shifted. Gunnery schools rewrote their curricula. Lieutenants learned to trust scopes and scopes alone in rain and smoke. Fire control crews practiced fighting without ever looking out a window.

The Japanese never really caught up. Survivors from Kirishima’s escorts argued for years about what had hit them. Some were sure there had been aircraft in the dark. Others insisted flares they’d never seen must have been dropped. The idea that a ship could see them with invisible waves and compute firing solutions with geared metal was outside their frame of reference.

Naval historians later called Washington’s fight the first true beyond-visual-range gunnery engagement. The phrase doesn’t capture the human part—the way old habits had to die in a single decision on a rain-swept bridge.

Willis Lee didn’t think of it as ceding control to a machine. He thought of it as learning just how blind men really were, and how much wider the world became when you taught yourself to “see” in another spectrum.

Washington survived the war. Her radar sets got smaller, faster, more capable. The Mark 8 became the ancestor of systems that would one day guide missiles halfway around the world and track targets in space. The principles born in Ironbottom Sound—trust in data, centralized fire control, engagement beyond sight—became standard operating procedure.

The ocean didn’t look any different afterward.

On the surface it was still just wind and water and black horizon. But underneath, in the way ships thought about each other, something had changed forever.

A technician from Washington, years later, rode a launch out over the place where Kirishima lay. The sea was calm. The sky was bright.

He slapped the water with his palm and said, half to himself, “She never saw us coming.”

It wasn’t boasting. It was simple recognition.

On that November night, light stopped being the final arbiter of what you could hit. Information took its place.

The age of vision ended in rain and radar echoes off Guadalcanal. The age of information began with the quiet sweep of a green line around a round piece of glass and an admiral willing to believe it.

News

After three years I came home and found my daughter sleeping in our laundry room

PART ONE: THE HOUSE THAT WASN’T MINE ANYMORE The rental car smelled like artificial pine and stale coffee, but I…

CH1 German Officers Predicted U.S. Artillery Would Fail — Until American Firepower Changed War Forever

You hear it before you see it. A low, distant growl that never quite stops. Every few seconds it swells,…

CH1 Joy Reid Reposts Viral Video Calling “Jingle Bells” Racist, Sparking Fresh Debate Over Christmas Classic

NEW YORK — Former MSNBC host Joy Reid reignited a familiar culture-war debate this week after reposting a viral video…

CH1 “The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming”

The searchlights swept the black water like fingers. Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse…

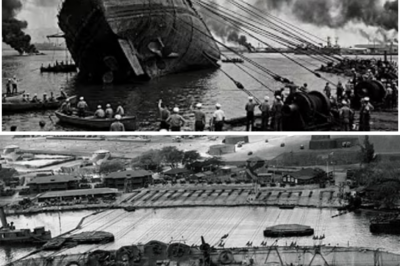

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

CH1 They Mocked His “Medieval” Airfield Trap — Until It Downed 6 Fighters Before They Even Took Off

The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42. Then another. Then four more in rapid succession. Six RAF fighters…

End of content

No more pages to load