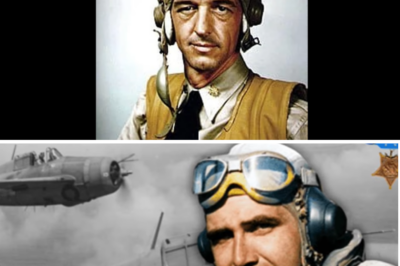

THE MAN WHO SHOULDN’T HAVE FLOWN — AND FLEW ANYWAY

Douglas Bader and the Day Tin Legs Met the Luftwaffe at 30,000 Feet

At 0745 on June 1st, 1940, Squadron Leader Douglas Bader pushed his Hawker Hurricane through the cold dawn air above Dunkirk—3,000 feet of altitude beneath him, the Channel shimmering like a sheet of steel far below—when a Messerschmitt Bf 109 slid into view.

Same direction.

Same speed.

Same altitude.

Two aircraft, closing the distance between them like two trains on parallel rails.

Bader was 29.

He had been in combat for exactly four weeks.

Nine years earlier he had lost both legs in a crash that should have ended his flying career permanently.

Now he had a German fighter sitting exactly 300 yards ahead of his gun sights.

No evasive action.

No sudden roll.

No burst of fire.

Just an invitation.

He squeezed the trigger.

And the story of the RAF’s most improbable ace began to reveal itself.

1931 — THE CRASH THAT SHOULD HAVE ENDED EVERYTHING

December 14th, 1931.

Woodley Airfield, near Reading.

Douglas Bader was 21, a rising star in No. 23 Squadron, one of the gifted young pilots flying Bristol Bulldogs.

Then came a stupid challenge from an Aero Club member:

“Bet you can’t slow-roll below 500 feet.”

Regulations forbade aerobatics below 2,000 feet.

Bader took off anyway.

He rolled at 200 feet.

The left wingtip kissed the grass.

The aircraft cartwheeled.

The Bulldog exploded.

Doctors amputated the right leg immediately.

Three days later, infection forced them to amputate the left.

Two stumps.

One above knee.

One below.

The Board of the RAF convened in March 1932.

Their decision was final:

No pilot with prosthetics. Ever.

Bader was retired at 21.

His logbook entry for the day of the crash was brutally short:

“Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show.”

That was Douglas Bader—concise, cutting, unbroken.

1932–1939 — WALKING AGAIN, BUT NOT FLYING

Shell Oil hired him.

He learned to walk on tin legs.

He learned to drive a modified car.

He played golf with a single-digit handicap.

But every night, the sky called him back.

Every day, he remembered the sound of a Merlin engine.

Every hour, he thought about flying.

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, he saw his chance.

He called everyone he knew at the Air Ministry.

They said no.

He called again.

They said maybe.

He called again.

And in November 1939, Central Flying School gave in.

They tested him.

They expected failure.

Instead, he flew rings around the examiners—loops, barrel rolls, spins, stall recoveries, clean precision flying they hadn’t seen in months.

In February 1940, the RAF reinstated him.

Douglas Bader—double amputee—was back.

FIRST KILL — THE 109 OVER DUNKIRK

June 1st, 1940.

He spotted the Messerschmitt.

400 rounds ready.

300 yards of clear air.

He fired—and missed.

The German still didn’t move.

He corrected, fired again, walked tracers straight into the canopy.

The 109 spiraled down toward the Channel trailing smoke.

First kill of 23.

JULY 1940 — TAKING COMMAND OF 242 SQUADRON

The RAF sent him to No. 242 Squadron—a Canadian outfit smashed in France, low on morale, low on parts, low on hope.

The squadron had aircraft but almost no spare parts, no tools, no fuel hoses, nothing to make them combat ready.

Bader sent a message to Group HQ:

“242 Squadron operational as regards pilots,

but non-operational—repeat, non-operational—regards equipment.”

The supplies arrived in 48 hours.

Leadership had arrived too.

SUMMER 1940 — THE ARTIFICIAL LEG ADVANTAGE

The Battle of Britain erupted.

Bader discovered something uncanny:

When British pilots pulled tight, high-G turns, blood drained from their legs and they blacked out.

Bader’s legs were aluminum and leather.

No blood.

No blackout.

No limit.

He could out-turn, out-climb, out-maneuver aircraft he should never have been able to fly.

And he became a legend for it.

AUGUST 9, 1941 — THE DAY THE GERMANS FINALLY GOT HIM

Bader had 23 kills.

Wing Commander.

Three squadrons under him.

Spitfire Mark VA, serial W3185.

He crossed the French coast with 48 aircraft behind him.

At 30,000 feet over Lille, he saw 12 Messerschmitts climbing toward him.

He dove.

Two kills in 90 seconds.

Then the world exploded.

A burst from behind.

A collision.

A fellow Spitfire.

A 109.

No one knows exactly what hit him.

But Bader’s Spitfire sheared in half.

The tail was gone.

Control cables snapped.

The aircraft fell into an inverted spin at 300 mph.

He tried to bail out.

His right prosthetic leg jammed under the control column.

10,000 feet.

He had seconds.

He unbuckled the upper strap.

Pulled.

Twisted.

The wind tore at him.

He pulled the parachute.

The shock ripped the remaining strap free.

His artificial leg stayed with the Spitfire as it smashed into the earth.

Douglas Bader descended into occupied France with one leg and no weapon.

CAPTURED — AND RECOGNIZED

German soldiers reached him within minutes.

He was taken to St. Omer Hospital.

Doctors were stunned.

A British ace with two artificial legs?

Word traveled fast.

Then the door opened.

Adolf Galland himself entered—Germany’s third-highest scoring ace.

He saluted Bader.

He asked what he needed.

Bader said one thing:

“I need my right leg.”

GALLAND PROMISED TO GET IT FOR HIM.

And he did.

THE RAF AIRDROPS A PROSTHETIC LEG

Galland sent a request through the Red Cross:

Allow an RAF aircraft safe passage to drop a replacement leg.

Hermann Göring approved it.

The RAF agreed—with a twist.

Six Blenheims flew over St. Omer.

One dropped the leg by parachute.

Then, instead of turning home peacefully…

…they bombed a power station 20 miles away.

The Germans were furious.

But the leg was delivered.

Bader strapped it on within minutes.

THE ESCAPE MACHINE — FIVE ATTEMPTS IN SEVEN MONTHS

The Germans didn’t know whom they had captured.

Bader tried escaping within five days.

Bed sheets tied together.

A two-story drop.

Caught.

Sent to Stalag Luft III.

He helped plan tunnels—Tom, Dick, Harry.

He forged documents.

He studied guard routines.

He attempted escape after escape after escape.

Finally, the Germans lost patience.

They sent him to Colditz, the escape-proof castle.

Even there, he tried.

Again.

And again.

They confiscated his prosthetic legs every night.

He kept trying anyway.

APRIL 1945 — LIBERATION

On April 16th, the U.S. 1st Army reached Colditz.

Douglas Bader walked out of the medieval fortress on two artificial legs, smiling as if he had merely finished a training exercise.

JUNE 1945 — LEADING THE VICTORY FLYPAST

June 15th, 1945.

London.

300 RAF aircraft assembled for Britain’s victory celebration.

Air Vice Marshal Leigh-Mallory chose one man to lead them:

Douglas Bader.

A man who wasn’t supposed to fly at all.

He flew at the head of 300 fighters over Buckingham Palace.

AFTER THE WAR — THE REAL LEGACY

Bader returned to Shell Oil.

He became a champion for amputees.

He visited hospitals.

He spoke to newly injured veterans.

He told them:

“A disabled man who fights back is not disabled.”

Books were written.

Films were made.

And in 1976, he was knighted.

When he died in 1982, Adolf Galland sent a wreath.

It read:

“To a great fighter pilot.

And a greater man.”

THE MEANING OF BADER

His 23 victories mattered.

His leadership mattered.

His escapes mattered.

But what mattered most was this:

He proved that disability is a circumstance, not a destiny.

That a man can lose both legs and still climb into a Spitfire.

Still fight at 30,000 feet.

Still escape German prisons.

Still lead 300 aircraft over London.

He proved that courage isn’t physical.

It’s a decision.

And he made that decision every single day.

News

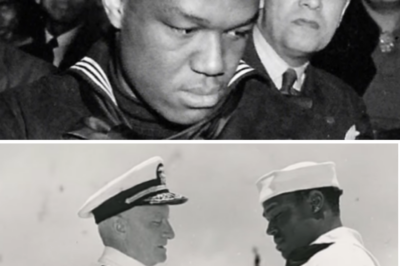

How One ‘Inexperienced’ U.S. Black Division Turned Japanese Patrols Into Surrenders (1944–45)

THE HUNT FOR THE LAST SAMURAI The 93rd Infantry Division, the Blue Helmets America Tried to Hide — and the…

They Grounded Him for Being “Too Old” — Then He Shot Down 27 Fighters in One Week

THE OLD MAN AND THE SKY THAT TRIED TO KILL HIM Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Thach and the Seven Days That…

Why Nimitz Refused To Enter MacArthur’s Pacific War Office – The Island Campaign Insult

THE EMPTY CHAIR IN BRISBANE How Two Men Won a War Together by Never Sitting in the Same Room The…

How One Black Cook’s “ILLEGAL” AA-Gun Grab Shook Pearl Harbor — And Forced the Navy to Change

THE COOK WHO DEFIÉD THE RULES OF WAR How a Mess Attendant With No Weapon, No Rank, and No Rights…

Billionaire Chases a Poor Girl Who Stole His Wallet… But the Truth She Reveals Shatters Him

PART 1 — THE CHASE THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING The morning sun rose over Los Angeles like liquid gold spilling across…

Billionaire Finds Homeless Boy Dancing for His Paralyzed Daughter… What Happens Next Will Shock You!

PART 1 — THE BOY WHO BROUGHT BACK THE SUN Riverside Avenue shimmered beneath the afternoon sun, a soft breeze…

End of content

No more pages to load