At 05:17 on the morning of September 13th, 1943, Private First Class William J. Crawford lay in a shallow scrape of dirt thirty-five meters below the crest of Hill 424 and watched German machine-gun tracers skate across the dark.

Twenty-eight years old.

From Pueblo, Colorado.

Zero confirmed kills.

Above him, three MG 34s from the 16th Panzergrenadier Division were dug into the rocky slope overlooking the Italian village of Altavilla. In the last six hours, those guns had killed nine men from Company I, 142nd Infantry Regiment, and pinned the rest of the company in place.

Crawford’s platoon sergeant had called his scouting skills “unremarkable.” Other NCOs said he moved “like a ranch hand checking fences—slow, methodical, no imagination.”

When he volunteered to crawl forward alone to find the exact positions of those MGs, Lt. Morrison’s first question was simple:

“Is this bravery or stupidity?”

Crawford answered the only way he knew how.

“Four years hunting mule deer in the San Isabel. Four-hundred-yard shots. All head shots. Don’t like wasting meat.”

Morrison’s answer was blunt.

“Stay in the goddamn hole. We’ll let artillery do the work.”

Crawford went anyway.

His “helmet trick” started right there: he took the most visible thing on his head and left it behind.

The Situation on Hill 424

The 36th Infantry Division had come ashore at Salerno on September 9th expecting light opposition.

They didn’t get it.

The Germans had turned every ridgeline and village around the Sele plain into observation posts and kill zones. Artillery was pre-registered on every approach. Machine guns like the three MG 34s above Altavilla covered the slopes with overlapping fire.

Hill 424 controlled the road net leading inland. Whoever owned that hill owned the routes off the beach.

Company I had already tried the textbook answer. At 23:00 on the 12th, they launched a frontal assault. They’d made maybe fifty meters before the guns opened.

Nine men didn’t come back. Fourteen crawled downhill bleeding.

The rest hugged rock until midnight and then seeped back to their start line.

Now Morrison’s platoon had one job: locate those guns before the 06:00 artillery barrage.

“Locate” meant getting close enough to see sandbag lines and muzzle flashes. Getting that close meant crawling across 150 meters of open ground while three MG 34s hosed every hint of movement.

Crawford packed light.

M1 Garand: eight rounds in the rifle, forty-eight more in six clips on his belt.

Three Mk II grenades.

Half a canteen of water.

He didn’t bring his helmet. The steel pot caught moonlight, turned a head into a target. He pulled a knit cap low instead. He rubbed mud into his wool uniform to kill the scent of soap.

Deer, he figured, could smell soap at 200 meters.

Germans probably weren’t much different.

The first MG 34 was about thirty meters directly ahead, behind a stone terrace wall built long before the war. Crawford had watched it for twenty minutes. It fired in short, professional bursts—8 to 12 rounds—traversing left to right, stitching the slope where his company lay pinned.

He could hear the crew between bursts. Calm. Confident. Pillbox kings.

The second and third guns were somewhere above and to his left, maybe seventy-five meters higher up, sited to sweep what the first gun couldn’t see.

He couldn’t go looking for them until the closest snake’s head was cut off.

Getting Close Enough to Die

At 05:23, Crawford started moving.

Not a low crawl, not a sprint. He inched forward on his stomach, elbows pulling, boots dragging. Face turned away so his cheek wouldn’t flash pale in the dark. He breathed through his mouth so air wouldn’t whistle in his nose.

Every ten meters, he stopped dead and listened.

The gun fired.

He counted.

Twelve rounds. Eighteen seconds until the next burst.

If he moved fast, he could cover three meters between shots.

Crawford didn’t move fast.

He moved right.

He lay through six more cycles, mapping the rhythm. Only when he knew the gun’s pattern—burst… pause… burst again—did he slide forward.

At 05:44, he felt stones under his fingers.

Terrace wall.

The MG 34’s barrel protruded from a gap four meters to his left. He could see the gunner’s shoulder, the assistant feeding the belt, a third man sitting casually with his back against the wall, smoking.

He eased a grenade off his belt.

At four meters, he didn’t have to lob it. Just drop it over.

A Mark II “pineapple” had a four- to five-second fuse and a lethal radius of about five meters. Everyone behind that wall was dead as soon as he let go.

They just didn’t know it yet.

He pulled the pin, kept the spoon pinned with his thumb, counted two seconds in his head, and then flipped it over the wall.

Metal clank. A shout in German.

He didn’t stay to watch.

He was already moving along the wall toward a rocky outcrop fifteen meters away.

He hit it just as a second MG 34 opened up. Rounds hammered the terrace where his body had been seconds before, stone chips hissing over his back.

From cover, he listened.

The second gun’s sound was higher on the hillside and off to the left. Echoes made exact location fuzzy—but he had what he needed:

Direction. Rough distance. Still blind to him.

The sky was lightening. He figured he had twenty minutes before dawn made him a shadow on a bare hillside.

He started climbing.

Not straight at the sound—that would have been suicide—but at an angle, using the old terrace steps as cover. One meter up. Crawl behind the next low wall. One meter up again. Repeat.

The second MG 34 was shooting in longer bursts now—twenty, thirty rounds at a time—hosing the lower slopes where Company I still hugged the rocks.

They had no idea one of their “unremarkable” scouts was ghosting his way past their tormentor.

The Helmet Trick

By 05:52, Crawford was about forty meters below and slightly off to the side of the second gun.

Now he could see it: two men at the weapon in a shallow dugout, sandbags stacked around their front and flanks. Barrel and sights pointed downslope. Their backs fully exposed to anyone who could get under them.

He flicked his eyes up the hill.

The third MG 34 sat roughly fifty meters above the second, tucked at the base of a rock outcrop near the crest.

It wasn’t firing.

It was the overwatch gun. Insurance. Waiting to cover the first two if anything went wrong.

Destroy the second gun, he realized, and the third gun owns you.

He was out of easy choices.

He crawled toward a small cluster of olive trees about twenty meters from the second gun, timing his movement with the bursts. Scrape only when the MG was barking. Freeze when it fell silent.

They never turned.

At 05:57, he reached the trees. From here, he could see up to the third gun as well.

He did the math.

He couldn’t kill both MGs at once.

So he changed the rules.

He yanked the pin on his third and final grenade and held the spoon.

Then he stood up.

It was the most dangerous thing he’d done all morning.

From behind the tree, he hurled the grenade at the second gun. His throw came up short; it landed a few meters in front of the sandbags and detonated against the rocks.

The blast sent a cone of dirt, stone, and shrapnel forward into the dugout, knocking at least one man flat. Smoke and dust boiled.

Crawford was already running uphill.

He covered twenty-five meters in about six seconds and dove behind the next terrace as the third MG 34 woke up.

Rounds smashed into the terrace face where he’d vanished, showering him with stone fragments. The gunner let the belt run long—forty, fifty rounds—trying to drown an area in lead.

Then the gun paused.

Reload.

Crawford hauled himself over the terrace and sprinted again, closing the gap to around twenty meters before shots snapped past and forced him behind a big boulder.

He was out of grenades.

He had his rifle. Eight rounds.

The MG 34 nest was well-built: sandbag walls, overhead cover. Shooting into it would be useless. The bullets would just chew cloth and dirt.

He needed the crew to come out.

He decided to make them think there was something worth chasing.

He should have had a helmet to stick up.

He’d left it behind on purpose.

So he made do with sound.

He eased the Garand up, picked a point above the sandbags, and fired a single round high, letting the supersonic crack snap right over the nest.

The gun fell silent.

Crawford waited.

Thirty seconds later, a head and shoulders appeared on the right edge of the position, trying to spot whoever had just fired at them.

Crawford shot him.

The MG 34 barked again, spraying the rocks around his last muzzle flash. Crawford rolled out of that spot, moved five meters along the terrace, tucked in behind another chunk of cover.

He fired again.

This time a different German edged out on the left side. Another careful peek.

Another shot. Another body.

The MG 34 went quiet.

He heard boots on rock. Voices. Two men leaving the gun pit, trying to flank the threat they thought was pinned down.

Crawford let them come.

At fifteen meters, moving cautiously through broken stone and scrub, they never saw him rise.

Four shots, fast and steady.

Two more down.

He ejected the empty en bloc clip. The Garand’s distinctive ping rang briefly in the quiet. He slid a fresh clip home, hit the bolt release, and moved up.

The MG 34 position was empty.

Two survivors had bolted upslope toward the crest.

The three guns that had turned the hillside into a death zone were silent.

It was 06:08.

The sun was just clearing the ridge.

Below Crawford, Company I was already starting to move again. The artillery that crashed in shortly after chewed up what was left. Within an hour, Hill 424 belonged to the 142nd Infantry.

Crawford had knocked out three machine-gun nests in fifty-one minutes using three grenades and twelve rifle rounds.

Company I took the hill with zero casualties in the assault.

Recognition (for Everyone But Him)

The same platoon sergeant who’d called Crawford “unremarkable” wrote him up for the Medal of Honor.

Lieutenant Morrison, who’d tried to keep him in his hole, co-signed.

Crawford didn’t get a medal on Hill 424.

As Company I consolidated on the crest, German troops counterattacked with infantry and armor from the north. Somewhere in the chaos, Crawford saw one of his squadmates lying out in the open, hit in both legs and unable to move.

He left cover to get him.

Halfway back, German patrols cut them off.

They took Crawford prisoner.

He spent the next twenty months as a POW.

Camps in Italy. Then Stalag VII-A in Bavaria after Italy surrendered. In German paperwork, he was just another line:

“PFC William J. Crawford, 36th Division. Captured Altavilla, 13 September 1943.”

No note about Hill 424.

No note about the recommendation for the Medal of Honor moving—slowly—through Army channels back in the States.

By the time the medal was approved on September 6th, 1944, Crawford was listed as “Missing in Action, Presumed Dead.”

In May 1944, in a small ceremony in Pueblo, Colorado, his father accepted his son’s Medal of Honor from a representative of President Franklin Roosevelt.

He put it in a frame on the mantle.

He did not know his son was still alive behind barbed wire in Europe.

Crawford was liberated in April 1945 when American forces overran Stalag VII-A. He came home weighing about 128 pounds, with scars on his lungs from tuberculosis and malnutrition etched into his frame.

The Army hospitalized him, then discharged him with disability pay in August 1945.

He went back to Pueblo. Married Eileen, the nurse who had helped pull him back from the edge. Bought a little house. Worked odd jobs that didn’t demand too much from his damaged lungs.

He didn’t talk about Altavilla.

He didn’t talk about the camps.

When people asked, he’d say, “I was in Italy with the 36th.”

Then he’d change the subject.

In 1947, he reenlisted—not to fight, but for the stability. He worked clerical jobs. Eventually, the Army stationed him at the brand-new U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs in 1954.

He became… the janitor.

The man who carried the trash. Who swept the halls. Who mopped the floors in cadet dorms.

Cadets saw him every day. Most never really saw him.

One would later recall him simply as “the quiet guy who cleaned our floor.”

The Janitor with a Medal of Honor

In 1984, a cadet named Bud Jacobs was working on a history project about Medal of Honor recipients from Colorado.

He found a name he didn’t recognize: William J. Crawford. Pueblo.

He kept digging.

Medal of Honor: yes.

Unit: 36th Infantry Division.

Place: Italy.

Death: reported 1944.

Then he cross-checked base employment records.

There it was:

“William J. Crawford. Janitor. 3rd floor, Vandenberg Hall.”

Jacobs took his research to the Academy Superintendent.

An investigation turned up a truth no one on that campus had suspected.

The quiet janitor with the mop had a Medal of Honor. He’d never stood on a parade field to get it. He’d never been properly recognized. The Army had given his medal to his father while he was still alive in a POW camp.

On February 8th, 1984, the Academy fixed that.

President Ronald Reagan came to Colorado Springs and, in front of around four thousand cadets, formally presented William J. Crawford with the Medal of Honor he’d earned forty-one years earlier.

Reagan read the Salerno citation: the crawling advance, the grenades, the solitary assault on machine-gun nests that had stopped a company cold. When he finished and put the ribbon around Crawford’s neck, the cadets stood and clapped.

They didn’t stop for four minutes.

Crawford kept his eyes mostly down. He didn’t give a speech.

When reporters asked him afterward what he thought, he said the same thing men like him always seem to say:

“I was just doing my job.”

He retired from the Academy in 1967 after twenty years of quietly keeping the place running. He and Eileen moved back to Pueblo.

He hunted again in the San Isabel National Forest, in the same country where he’d learned how to move without spooking mule deer and how to kill with one clean shot.

He died on March 15th, 2000, of natural causes at Palmer Lake, Colorado. He was eighty-one.

Colorado’s governor ordered flags to half-staff.

He was buried with full military honors in the Air Force Academy cemetery.

The Legacy of a “Ranch Hand”

The Army never put “Helmet Trick” into any manual, but they did put Crawford’s tactics there.

Infantry schools picked apart Altavilla not as legend, but as a case study:

How to use terrain and timing to approach fortified positions

How to target crew-served weapons before worrying about riflemen

How well-placed grenades and baiting fire can dismantle machine-gun nests

How one patient, determined soldier can do what a full company sometimes cannot

Field manuals published in 1946 and updated through the 1950s reflected those lessons—lessons taught by a man whose name never appeared in the footnotes.

By the time Vietnam rolled around, scout and recon troops were being formally trained in infiltration work that had its roots on that rocky Italian hill: moving on your belly, counting bursts, creeping inside fields of fire, pulling the trigger only when it mattered.

The ranch hand from Pueblo, who moved like he was checking fence lines, had shown what could happen when you mix hunting skills with a refusal to stay where you’re told when you know you can help.

He didn’t storm a hill in a Hollywood charge. He didn’t take a screaming run at a gun.

He left his helmet behind, slid through the dark, counted shots, and made every grenade and bullet matter.

Company I took Hill 424 with zero assault casualties because of what he did.

The hill itself changed hands several times after that. Its “tactical value” lasted maybe seventy-two hours before armor pushed the Americans back.

But the doctrinal value—the way of thinking about what one person can do with patience and skill—that lasted decades.

Crawford never bragged about any of this.

He once told Eileen that the men who followed orders and went straight up the slope into machine-gun fire deserved the medals more than he did.

He’d broken orders and gone alone, which meant if anyone died, it was supposed to be just him.

He didn’t consider that heroism.

He considered it the practical thing to do.

News

Halle Berry Stuns DealBook Summit With Sharp Rebuke of Gov. Gavin Newsom Over Vetoes of Menopause Care Bill

NEW YORK — December 3, 2025.Actor and entrepreneur Halle Berry, 59, delivered one of the most talked-about moments at The…

‘RHOA’ Star Kandi Burruss Allegedly Caught Todd Tucker ‘Talking to Other Women’ Before Filing for Divorce: Report

The breakdown of Kandi Burruss and Todd Tucker’s 11-year marriage may not have been as sudden as fans thought. According…

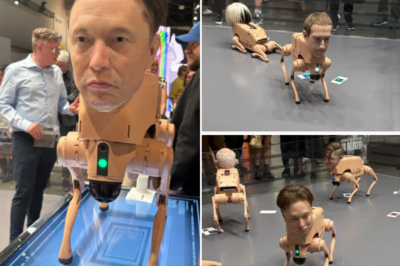

Beeple’s Wild Art Basel Spectacle: Musk, Bezos & Zuckerberg Robot Dogs Pooping NFTs Stop Miami in Its Tracks

Only at Art Basel Miami Beach could you turn a corner and find Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg…

Why Pregnant Alyssa Farah Griffin Has Been Absent From The View

Fans tuning in to The View this week may have noticed one seat consistently empty: Alyssa Farah Griffin’s. The 35-year-old…

Pramila Jayapal Says Mass Deportations of Somali Fraud Suspects Would “Hurt the U.S. Economy” — Sparks Outrage in Immigration Fight

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) is facing fierce political backlash after arguing on MS NOW Thursday that deporting Somali immigrants tied…

Inside Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s swanky Rhode Island wedding venue

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce are officially leaning into full-scale, coastal luxury for what is already shaping up to be…

End of content

No more pages to load