At 05:17 on the morning of September 13th, 1943, Private First Class William J. Crawford lay in a shallow scrape of dirt thirty-five meters below the crest of Hill 424, watching German machine-gun tracers draw flat, glowing lines across the dark.

He was twenty-eight years old, from Pueblo, Colorado. Four years of hunting mule deer in the San Isabel National Forest. Zero confirmed kills in combat.

Above him, three MG 34s from the 16th Panzergrenadier Division were dug into the rocky slope above the Italian village of Altavilla, and in the previous six hours those guns had killed nine men from Company I, 142nd Infantry Regiment.

His platoon sergeant thought his scouting skills were “unremarkable.”

Other squad leaders said he moved through terrain like a ranch hand checking fence lines—slow, methodical, practical, but without “tactical imagination.”

So when Crawford volunteered to crawl forward alone and find those German positions, Lieutenant Morrison had to ask if this was bravery or stupidity.

Crawford explained, in his flat Colorado way, that he’d spent four years taking head shots on mule deer at 400 yards to save meat, that he knew how to move quiet and see without being seen.

Morrison told him to stay in the “goddamn hole” and wait for the 0600 artillery barrage.

Crawford went anyway.

The 36th Infantry Division had come ashore at Salerno on September 9th expecting relatively light resistance. Instead, they found German units on every piece of high ground overlooking the Sele Plain. Observation posts with perfect views. Artillery pre-registered on every approach. Machine guns dug in where advancing troops would have to cross open terrain.

Altavilla sat at about 420 meters above sea level, on steep volcanic limestone with only thin scrub, scattered olive trees, and old stone terraces carved by farmers who’d run when the fighting started.

Hill 424 controlled the road inland from the beachhead. The Germans held it with roughly two companies—around two hundred men—with mortars and those three MG 34s that were now shredding every attempt to move up.

Company I had tried a frontal assault at 2300 on the 12th. They’d made it fifty meters uphill before the machine guns opened. Nine dead, fourteen wounded. The survivors hugged the rocks until after midnight and crawled back down.

Morrison’s platoon had been told to locate the guns for the artillery prep. Locating meant closing to within grenade range. Closing meant crossing 150 meters of broken rock while three machine-gun teams traced interlocking arcs over the slope.

Crawford carried an M1 Garand, 8 rounds in the rifle, 48 more in six clips on his belt. Three Mk II fragmentation grenades. A half-full canteen. No helmet—he’d left it behind, knowing that curved steel flashed in moonlight. Instead he wore a knit cap pulled down. He had rubbed mud into his uniform to kill the scent of GI soap.

Deer could smell soap at 200 meters, he figured. Germans probably could too.

The first machine gun was about thirty meters directly ahead, behind a low stone terrace wall. Crawford had been watching it for twenty minutes. The crew fired 8- to 12-round bursts, sweeping left to right, covering the slope in a mechanical rhythm. Between bursts, he heard them talking—calm, professional.

The other two guns were somewhere up and to his left, seventy-five meters higher, covering the dead ground the first couldn’t reach. He hadn’t seen them yet. He knew he’d have to kill the closest gun before he could go hunting for the others.

At 0523, he started moving.

Not a low crawl. Not a rush. Just a slow, belly-down slide over rock and dirt. Elbows pulling, boots dragging. His face turned to the side so his cheek wouldn’t catch any faint light. He breathed through his mouth so air wouldn’t whistle in his nose.

He listened.

The gun fired. Twelve rounds. Silence. He started counting in his head. Eighteen seconds between bursts. Enough to move three meters if he sprinted.

Crawford didn’t sprint. He watched the pattern through six more bursts. Confirmed it. Mapped it.

Then he slid forward again.

It took him twenty minutes to close those last thirty yards.

At 0544, he was tucked against the terrace wall. The MG 34 barrel stuck out two meters to his left. He could see the gunner’s shoulder through a gap, the assistant feeding the belt, a third man sitting with his back to the stones, smoking.

He eased one grenade out of his belt.

At four meters, the Mk II’s five-meter lethal radius would turn that little nest into a blender. But the explosion would shout a warning up the slope. The other guns would swing toward him. He’d have maybe ten seconds of confusion before the hillside lit up again.

He pulled the pin, held the spoon down, counted one… two… then flipped it over the wall.

Metal clanked, someone shouted “Granate!” and the world snapped white.

Crawford didn’t stay to admire his work. He was already moving along the terrace, toward a rock outcrop fifteen meters away. He’d barely thrown himself into its shadow when the second gun opened. Heavy rounds tore into the wall where he’d been seconds before. Stone fragments whickered over his head.

He pressed himself into the rock and listened.

The second gun was upslope and left, sixty meters maybe. Echoes bounced off the hillside. Hard to pin, but he didn’t need a grid coordinate. He needed a general direction and a sense of distance. He had both.

The sky was going gray. He figured he had twenty minutes until full dawn. Once the light came up, German observers on the crest would see any movement and bring down everything on it.

He started climbing—not straight at the gun, but at an angle, using the old terrace walls as stepping stones. Each one was about a meter high. He hauled himself up, crawled along the thin strip of dirt, then hugged the rocks and did it again.

The second machine gun was firing longer bursts now—20, 30 rounds—raking the lower slope where Company I still lay pinned. They hadn’t seen him. They weren’t looking for him. They were firing at muzzle flashes two hundred meters downslope.

At 0552, Crawford lay behind a terrace forty meters below them. He could see the gun now: dug into a little scraped-out depression, sandbags piled in front, two men visible at the weapon. Their backs were to him, entirely focused on killing his friends.

Too far to throw accurately. Thirty-five meters. He needed to close.

He left cover and slithered across loose volcanic soil toward a clump of olive trees twenty meters from the nest. The ground was thin and gravelly. Every movement made small, betraying scrapes. He moved during the long bursts when the gun’s own noise covered his sound, froze when it stopped.

They never looked back.

At 0557, he reached the trees.

From that angle, he could see the third gun—fifty meters above the second, tucked at the base of a rock outcrop near the crest. That one was silent. You didn’t waste ammunition in a properly set-up defense. One gun engaged. Another covered.

If he killed the second gun with the third intact, he’d never make it to cover. They’d saw him apart on the slope.

He had one grenade left.

He pulled the pin and held the spoon. Then, for the first time that morning, he stood up.

Half-hidden by the olive trunks, he exposed his upper body, swung his arm, and threw.

The grenade came up just short, bouncing on the rocks three meters in front of the sandbags and exploding forward into the position. He saw one German thrown back.

Then he ran—not down, but up. Straight at the third gun.

He covered twenty-five meters in six seconds and dove behind another terrace just as the MG 34 up top came alive. Rounds ripped into stone, showering him with chips.

Now the third gun knew someone was here. It didn’t know exactly where.

The gunner fired long, wasteful bursts at the terraces, trying to drown the slope in fire. Crawford heard the belt rattle empty. Heard shouting as the crew fumbled a fresh belt into place.

He hauled himself over the terrace and sprinted again, zigzagging, another fifteen meters closer before diving behind a boulder.

Twenty meters now. Close enough.

He had no grenades left. The MG 34 was dug in behind sandbags with overhead cover. His rifle rounds wouldn’t chew through. He needed the crew to come out. To come to him.

He fired once, deliberately high, so the bullet cracked above their heads.

The gun fell silent.

He waited.

Boots on rock. A head and shoulders appeared at the right edge of the sandbags, searching. Crawford squeezed the trigger. The man dropped.

The machine gun spat again, blind, chewing the ground where his muzzle flash had been. Crawford rolled sideways behind another rock. Fired again.

A second German appeared on the opposite side of the nest. Crawford put him down, too.

Silence. Then urgent voices. Scrambling feet. Two figures breaking cover, flanking out to work around his position.

He held his breath and stayed low.

At fifteen meters, he stood and fired four quick shots.

Both men fell.

He reloaded—the Garand’s clip pinging free, another snapping into place. Then he moved forward, rifle at the ready.

The machine-gun position was empty when he reached it. Blood on the sandbags. An MG 34 warm under his hand. Two dead men near where he’d shot them. The survivors had broken and run over the crest.

At 0608, as the sun pushed over the ridge, William Crawford was standing next to that third machine gun, looking down on the whole slope.

Below, Company I saw the gun that had held them all night suddenly fall silent.

Then they saw a single American silhouette appear next to it.

They got up and moved.

The hill fell within the hour. With the machine guns gone, the German line cracked. By 0900, the 142nd Infantry Regiment held the crest of Hill 424.

Crawford had taken out three machine-gun positions in fifty-one minutes using three grenades and twelve rifle shots.

Not one man from his company died in the final assault.

His platoon sergeant, who had once called his scouting “unremarkable,” put him in for the Medal of Honor. Morrison co-signed the recommendation.

Crawford didn’t receive it on Hill 424.

As Company I dug in, German troops counterattacked from the north with infantry and armor, trying to claw back the high ground. In the chaos, Crawford saw one of his own lying in the open, hit through both legs.

He left cover to get him.

He was dragging the wounded man back when a German patrol swept around a fold in the ground and took them both. Crawford went into captivity on the same day he’d earned the nation’s highest award.

The paperwork for his medal took a slower route.

He was shipped through a chain of camps in Italy, then to Stalag 7A in Bavaria after Italy’s surrender. In German records he was just another POW: PFC William J. Crawford, captured September 13th, 1943, Altavilla.

In American records, he was missing and presumed dead. By the time the Medal of Honor was approved on September 6th, 1944, the Army believed he’d fallen in Italy.

On May 11th, 1944, in a ceremony in Pueblo, Colorado, his father accepted his son’s medal “posthumously.” President Roosevelt’s signature was on the citation. The framed medal went on the mantle in the family home.

Crawford, very much alive, stayed behind barbed wire until April 1945, when advancing American troops overran Stalag 7A. When he came home, he weighed about 130 pounds and carried tuberculosis scars in his lungs.

He spent months in Army hospitals. Was discharged in August 1945 with a disability pension. He went back to Pueblo, married a nurse named Eileen Bruce, tried to build a quiet life.

He didn’t talk about Altavilla.

Ask him, and he’d say he’d “been in Italy with the 36th” and change the subject.

In 1947, he re-enlisted. Not as an infantryman—his lungs wouldn’t allow it. He signed up for clerical work. The Army put him behind desks, in orderly rooms, anywhere his quiet reliability could be used.

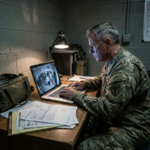

In 1954, when the new U.S. Air Force Academy opened in Colorado Springs, Crawford ended up there. Not as an instructor. Not on staff.

As a janitor.

He mopped the dormitory floors. Cleaned the latrines. Emptied trash cans. Fixed stuck windows. He wore civilian clothes and a name tag.

Cadets passed him every day. Some nodded. Most didn’t. One later recalled, “He never said much. Just did his job.”

Above their heads, in classrooms, they learned about the Medal of Honor and read citations from men who had done impossible things.

None of them knew one of those names lived down the hall with a broom in his hand.

That changed in 1984.

Cadet Bud Jacobsen, researching Medal of Honor recipients from Colorado for a history paper, found the name “William J. Crawford, Pueblo” on a list. He got curious. He dug deeper. The records said Crawford had earned his medal with the 36th Division in Italy and had died.

But another record—on a civilian employee roster—said a William J. Crawford, Pueblo, worked third-floor janitorial duty.

Jacobsen walked down and looked at the man pushing the mop.

Then he took what he’d found to the Academy superintendent.

The investigation that followed confirmed what the papers said and reality denied: the Army had given Crawford’s medal to his father assuming he was dead. No one had ever corrected the record. Crawford had never walked across a stage, never been saluted for what he’d done. The janitor everyone called “Mister Crawford” was, in fact, a living Medal of Honor recipient.

On February 8th, 1984, standing on the parade ground in front of 4,000 cadets, sixty-five-year-old William J. Crawford finally received his medal in person from President Ronald Reagan.

Reagan read the Salerno citation. The three machine-gun nests. The crawling advance. The grenades thrown at close range. The rifle shots that finished what explosives had begun.

When the President placed the ribbon around his neck, the cadet wing erupted.

They applauded for four straight minutes.

Crawford didn’t give a speech.

Asked later what he thought, he said, “I was just doing my job.”

He retired from civil service in 1967 and moved back to Pueblo. He hunted in the San Isabel National Forest, the same ridges where he’d learned to shoot before the war. He lived quietly with Eileen.

He died on March 15th, 2000, at Palmer Lake, Colorado, age eighty-one. The governor ordered flags to half-staff. He was buried with full military honors in the cemetery at the Air Force Academy.

The Army never forgot Hill 424, even if most of the world never knew the name.

Infantry schools used the fight at Altavilla as a case study—not for its drama, but for its mechanics. The way Crawford used terrain to close with the enemy. How he timed his movement to their fire. How he targeted the machine guns first, knowing that three men behind an MG 34 were more dangerous than thirty with rifles. How a single soldier, moving slowly, methodically, could do what artillery and frontal attacks could not.

Those lessons were written into field manuals in 1946 and refined in the decades that followed. By Vietnam, American scouts and small-unit leaders were being trained in techniques that traced directly back to what a quiet ranch hand from Pueblo had done on a rocky slope in Italy: infiltration, close-range grenade use, independent action without constant orders.

Crawford never claimed any of that for himself. He told his wife once that the real heroes were the men who followed orders and charged uphill under machine-gun fire, knowing they might die.

He had disobeyed an order when he left his hole to crawl forward. If the plan failed, he figured, only one man would die.

He didn’t consider that heroism.

He considered it practical.

The Army considered it something else.

And generations of soldiers learned, from a story most never connected to the name of the janitor in their hallway, that sometimes the most decisive act on a battlefield isn’t a grand charge or a clever plan.

It’s one person, moving slowly, thinking clearly, and refusing to stay in the hole when everyone else is pinned there.

News

America Copied Germany’s Jerry Can — But Missed The One Genius Detail that Made All the Difference

70,000 gallons of fuel left the depot in North Africa. 30,000 gallons reached the front. A 57% loss. The quartermaster…

How the American Jeep Shocked the Germans on D-Day

June 7th, 1944. Just inland from Utah Beach, near Saint-Mère-Église. Oberleutnant Klaus Müller of the German 709th Infantry Division stood…

They Mocked His “Homemade Grenade” — Until It Took Out 31 Germans in a Single Night

December 22nd, 1944. 0115 hours. Bône, Belgium. The frozen ground shook with each distant artillery blast as Corporal James Earl…

A special education teacher discovers that his non-verbal autistic student has been learning and understanding far more than anyone realized when the boy uses incredible skills to save his teacher’s life during a medical emergency. This story will change how you think about autism, communication, and the hidden potential in every child.

Chapter 1 – The Boy No One Could Reach For three years, people told me I was wasting my time…

Frank Jacobs is 67 years old, retired, widowed, and alone. His son Michael died in a car accident 13 years ago. His wife Ellen died 5 years later. He thought he was the last Jacobs—the end of his family line. Then he gets a call from Child Protective Services: “Mr. Jacobs, did you know you have a grandson?”

Chapter 1 – The Phone Call I was sixty-seven years old, and until six months ago I thought I knew…

Scott Lewis is a hotel cleaner who writes novels at night that nobody will publish. When his favorite author, Edward Koy—a reclusive Pulitzer Prize winner—checks into the hotel, Scott is starstruck but professional. One day while cleaning Koy’s suite, Scott finds crumpled manuscript pages in the trash. He reads them and realizes the scene isn’t working. In a moment of reckless courage, Scott rewrites it and leaves it on Koy’s desk with a note: “A fan who couldn’t help himself.” The next day, he’s called to the manager’s office, certain he’s getting fired.

Chapter 1 – The Pages in the Trash By any reasonable measure, I was a professional failure. By day, I…

End of content

No more pages to load