“Impossible. Unmöglich.”

That was the mood inside German high command when the first reports came in.

On December 19, 1944, American General George S. Patton announced something every German officer instinctively dismissed as fantasy. He would pull three full divisions out of ongoing combat, swing his entire army 90 degrees to the north, march them through one of the worst winters in decades, and hit the southern flank of the German Ardennes offensive—within 48 hours.

To German commanders, it sounded absurd.

Intelligence officers called it Allied propaganda. Senior generals scoffed. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt stated flatly that no army could carry out such a maneuver in less than a week. They all trusted their doctrine, their experience, their calculations.

They were all wrong.

And their own words—captured through radio intercepts, diaries, and post-war interrogations—show just how deeply Patton’s “impossible” move shook German confidence and helped flip the Battle of the Bulge from potential German success to catastrophic failure.

“This is deception”

When German signals units first picked up American traffic about Patton’s Third Army pivoting north, no one panicked. The reaction was ridicule.

In the headquarters of Army Group B, Field Marshal Walter Model read the report and brushed it aside as a trick.

“Patton is fighting in the Saar,” he told his staff. “This is a ruse to make us believe he can be in two places at once.”

German planning for the Ardennes offensive—code-named Wacht am Rhein—rested on one crucial assumption:

The Allies would need at least a week to shift significant forces to plug the breakthrough.

German staff officers had studied Allied procedures, their logistics, their command habits. Moving large formations, they believed, demanded detailed planning, complicated supply coordination, and time. A 90-degree turn of three divisions in winter conditions? Two weeks sounded realistic. Three weeks, safer.

Colonel General Alfred Jodl, chief of operations at OKW, reacted in a colder, more analytical way. In his diary entry for December 19, he noted:

American radio traffic indicates that Patton’s Third Army intends to strike our southern flank within 48 hours. Either this is a psychological operation designed to unsettle us, or American commanders have completely lost contact with reality. No army has ever attempted such a maneuver under such conditions within such a time frame.

Even Heinz Guderian, the architect of German armored warfare, couldn’t accept it. When told of Patton’s intentions, he reportedly remarked:

“If Patton truly manages this, I will have to rewrite everything I know about armored operations.”

Guderian understood tanks, fuel, and logistics better than almost anyone. He knew what it meant to move entire divisions: the fuel convoys, the maintenance, the traffic control, the staff work. What Patton was proposing seemed to break every rule of operational art.

As a result, German field units on the southern edge of the Bulge were warned to expect American counterattacks—but in several days, not immediately. Frontline formations were ordered to push west, not to dig in facing south.

The understrength German Seventh Army, which held the southern shoulder, received only modest reserves. The high command simply did not believe a major American blow could arrive so quickly.

That disbelief was Germany’s first major error. By the time they realized Patton wasn’t bluffing, the window to adjust their own plans had slammed shut.

“How are they doing this?”

By December 21, 1944, unease began to creep into German headquarters.

Reconnaissance units reported heavy American movements heading north out of the Saar area. These were not small detachments but full divisions, complete with supply columns and support units. Radio intercepts confirmed that Third Army units were breaking off contact and redeploying.

Despite the brutal weather, Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes—when they could get airborne—spotted endless lines of American vehicles grinding their way through snow and ice.

At Army Group B, Model’s attitude changed completely. His chief of staff, General Hans Krebs, later recorded how Model paced up and down the command post, repeatedly demanding an explanation. How, he wanted to know, were the Americans doing in two days what his staff had calculated would take at least two weeks?

German logistics officers checked the numbers and came to an unsettling conclusion:

To move three full divisions—with roughly 133,000 men, 11,000 vehicles, tanks, guns, ammunition, fuel, and supplies—through winter conditions on clogged roads shared with other Allied traffic should have been beyond reach.

One German quartermaster wrote:

“Either the Americans have developed supernatural powers, or our understanding of logistics is fundamentally incorrect.”

The psychological effect was enormous. German strategy in the Ardennes depended on Allied slowness and predictability. Suddenly, that bedrock assumption was crumbling. If Patton could do this, what else might the Americans be capable of?

General der Panzertruppe Hasso von Manteuffel, commanding Fifth Panzer Army, quickly understood the danger. He sent an urgent warning to Model:

If Third Army struck hard at the southern flank while German spearheads pushed west, the leading units would be cut off.

His message was blunt: either accelerate the drive to the Meuse at once, or start preparing defenses facing south.

But acceleration was no longer realistic. German spearheads were already bogged down by fierce resistance at St. Vith and Bastogne. Fuel was running low. The plan had depended on capturing Allied fuel dumps, but American troops had fought too stubbornly to allow that.

German tanks were literally stopping for lack of gasoline.

The contrast was bitterly ironic to German officers. While their own vaunted panzer divisions were stranded by empty fuel tanks, Patton was somehow driving three divisions through a blizzard.

Colonel Hans von Luck, a panzer commander, later wrote:

“We began to understand that we were facing an enemy whose capabilities we had underestimated. The Americans, whom we had considered amateurs, were now outmaneuvering us with an operational flexibility we could no longer match.”

“This is not a probe. This is a major offensive.”

By December 22, alarm replaced concern. Patton’s men were not just on the move—they were forming attack positions.

This was no feint and no deception. It was real. And German high command had no ready-made plan to counter it.

At 6:00 a.m. on December 22, 1944, Patton’s Fourth Armored Division slammed into German lines on the southern flank of the Bulge. The effect was immediate and devastating.

Units that had been assured they had several days to prepare were struck by a full-scale American armored assault little more than 72 hours after Patton had announced his intentions.

The Seventh Army’s headquarters descended into panic. General der Panzertruppe Erich Brandenberger, commanding the southern shoulder, radioed Army Group B in desperation:

Under heavy attack by American armor. Multiple divisions. This is not a reconnaissance thrust. This is a major offensive. Patton has actually done it.

Field Marshal Model’s reply, preserved in the records, showed his shock:

Confirm that this is Third Army. Confirm Patton is personally directing the attack. How is this possible?

When confirmation arrived that it was indeed Patton’s army attacking in strength, Model reportedly hurled down his marshal’s baton and said:

“We are fighting a genius.”

On the front line, German soldiers were just as stunned. Lieutenant Hans Schmidt, facing Fourth Armored Division, wrote in his diary:

“The Americans emerged from the snowstorm like ghosts. We had been told they could not reach us for days. Yet they appeared in great strength, attacking with a coordination and fury we had never seen. They fought as if possessed.”

In Berlin, the mood in the high command darkened. Hitler had confidently proclaimed that the Americans would need at least ten days to respond effectively to the Ardennes offensive.

Patton proved him wrong in less than three.

Hitler’s reaction followed a familiar pattern: he blamed his intelligence officers for incompetence and his generals for weakness. He refused to admit that an American commander had simply out-thought and out-executed German planning.

His professional officers, however, knew exactly what had happened.

General der Infanterie Günther Blumentritt, chief of staff to von Rundstedt, later wrote:

“Patton’s relief of Bastogne is one of the most remarkable operational feats of the war. To disengage from combat, move three divisions through winter conditions, and launch a coordinated attack within 48 hours demanded staff work, logistical coordination, and command skill beyond anything we achieved—even in our victories of 1940.”

The southern flank of the German offensive began to buckle. Units that were supposed to be driving westward were now fighting desperately just to hold their positions against Third Army’s onslaught. The already-delayed German timetable completely collapsed.

Patton’s blow did more than save Bastogne; it wrecked the operational logic of the entire Ardennes plan.

“We are no longer fighting the Allies of 1942.”

When Fourth Armored Division finally broke through to Bastogne on December 26, 1944, German high command could no longer deny the truth: the Ardennes offensive had failed.

Not just because of heroic American defenses—though those mattered. Not just because of fuel shortages—though those were crippling. It failed because Patton accomplished what German planners had considered impossible.

On December 27, von Rundstedt convened a command conference. The captured minutes of that meeting later revealed the depth of their frustration.

“We built this operation,” he told his generals, “on the belief that the Allied reaction would be slow, fragmented, and passive. Patton has shown how disastrously wrong that assumption was. We are no longer fighting the hesitant, cautious Allies of 1942 and 1943. We are facing an enemy who now operates with a speed and determination that equals or surpasses our own.”

The consequences were clear. If the Americans could swing three divisions 90 degrees in two days, then German massing of forces was no longer safe. Any buildup could be met by a rapid American counterstroke.

The entire German concept of surprise offensives—the heart of their doctrine—was now undermined by an enemy with superior operational agility.

Panzer leaders felt it keenly. General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, whose troops were pulled away from the drive to the Meuse to counter Patton, later wrote bitterly:

“We invented the theory of mobile armored warfare. We wrote the manuals on rapid maneuver and exploitation. Now an American general was applying our own ideas against us—and in some respects, doing it better. It was a bitter realization.”

At Hitler’s headquarters, the Führer’s answer was predictable: keep attacking, feed more forces into the failing offensive, insist that “willpower” could overcome reality.

But Model, Manteuffel, von Rundstedt and others privately agreed: the offensive was finished. Patton’s dash to Bastogne had proved that American forces could react faster than German forces could exploit a breakthrough.

The psychological impact spread through the ranks. German soldiers had been told for years that the Americans were poorly led, poorly trained, and lacked German discipline and skill.

Patton’s maneuver shattered that myth. Men who had once marched confidently across Europe now faced an opponent who could out-think, out-maneuver, and outfight them.

The Battle of the Bulge dragged on, but for many German officers, the outcome was decided by December 26. Patton’s “48-hour miracle” hadn’t just saved a single encircled town—it had broken the spine of Germany’s last great offensive and shown that American military power had overtaken German expertise.

What German commanders said after the war

After Germany surrendered, Allied interrogators repeatedly asked captured generals about Patton and the relief of Bastogne. The answers were revealing. These were not excuses, but attempts by professionals to understand how they had been so thoroughly outplayed.

Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, head of the OKW, was questioned in May 1945. When Patton’s name came up, he admitted:

“We made the mistake of believing our own propaganda about American military incompetence. Patton destroyed that illusion. His ability to move an entire army through a blizzard and attack within 48 hours showed an operational skill we could not match in 1944. Perhaps we could have done it in 1940, at our peak. By 1944, we had lost that ability. Patton still had it—or the Americans had learned it.”

General der Panzertruppe Hermann Balck, one of Germany’s most respected field commanders, offered a clinical assessment:

“Patton understood a crucial principle: in modern war, the side that can react faster dominates the operational tempo. He did not wait for ideal conditions or perfect information. He acted with what he had. This is what we did in our early victories. By 1944, we had grown cautious and slow. Patton remained bold and rapid. That difference decided the outcome.”

Even Model, who had directly opposed Third Army in the Ardennes, conceded Patton’s brilliance. Before his suicide in April 1945, he reportedly told his staff:

“If Germany had possessed commanders who could operate with Patton’s speed and flexibility, we would have won this war. Our early victories made us arrogant. We believed our doctrine was superior. Patton showed that doctrine is less important than execution—and his execution was flawless.”

Heinz Guderian, who had originally joked that he would have to rewrite his understanding of armored warfare if Patton succeeded, later admitted in interviews:

“I did not believe it possible. The logistics alone should have required a week of preparation. The march through winter conditions should have been chaotic. The attack should have been fragmented and uncoordinated. Instead, Patton achieved near-perfect synchronization. His staff work, his commanders, his logisticians—they all performed superbly. This was not luck. It was operational excellence at every level.”

In the postwar years, German military historians echoed these judgments. General der Infanterie Hans Speidel, who had served as Rommel’s chief of staff, wrote:

“The relief of Bastogne is one of the finest demonstrations of operational art ever conducted. It should be studied in every war college—not only for what Patton did, but for how an entire army carried out such an order under seemingly impossible conditions.”

Perhaps the most telling verdict, though, came from ordinary German soldiers sitting in POW camps after the war. Many of them pointed to Third Army’s turn to Bastogne as the moment they realized the war was lost.

One former panzer officer put it simply:

“When Patton turned his army in a blizzard and attacked within two days, we knew we were beaten. Not just beaten in that battle—but beaten in the war. We no longer had the leadership or the ability to match such an enemy.”

Patton’s own men already knew what their enemies were only discovering:

“Old Blood and Guts” was not just a showman with pearl-handled pistols. He was an operational mastermind who could do what others dismissed as impossible.

News

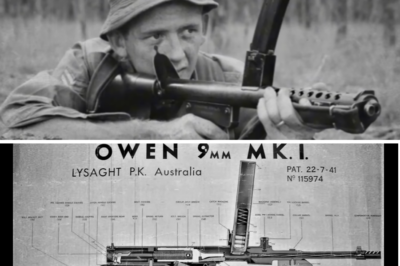

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

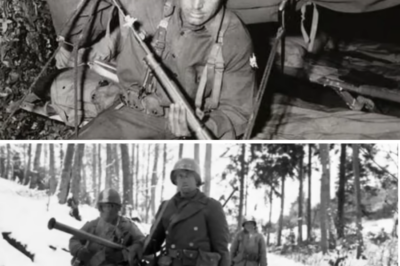

They Banned His “Rust Lock” Rifle — Until He Shot 9 Germans in 48 Hours

THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb…

German POWs Couldn’t Believe American Farmers Had 3 Tractors Each

THE PRISONER AND THE TRACTOR How a German POW in Minnesota Discovered the Lie That Built the Third Reich —…

How One ‘Inexperienced’ U.S. Black Division Turned Japanese Patrols Into Surrenders (1944–45)

THE HUNT FOR THE LAST SAMURAI The 93rd Infantry Division, the Blue Helmets America Tried to Hide — and the…

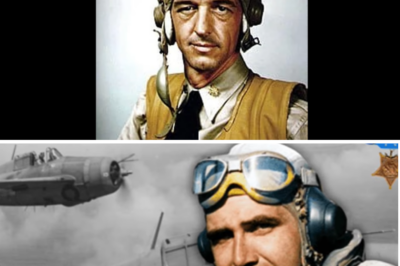

They Grounded Him for Being “Too Old” — Then He Shot Down 27 Fighters in One Week

THE OLD MAN AND THE SKY THAT TRIED TO KILL HIM Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Thach and the Seven Days That…

Germans Laughed at This ‘Legless Pilot’ — Until He Destroyed 21 of Their Fighters

THE MAN WHO SHOULDN’T HAVE FLOWN — AND FLEW ANYWAY Douglas Bader and the Day Tin Legs Met the Luftwaffe…

End of content

No more pages to load