War has many sounds: the crack of rifles, the thunder of artillery, the metallic howl of treads grinding over stone.

But in the summer of 1944, in the hedgerows of Normandy, the sound that terrified American tank crews most was something else entirely.

A hollow metallic whoomp.

The sound of a German 75 mm or 88 mm round punching through the side of an American Sherman.

What came next was worse: the rush of oxygen, the explosive cough of gasoline, the shriek of men trapped inside a steel box that had just become an oven.

By July, the United States Army had turned that horror into an equation.

They knew, on paper, how long a tank crew would live.

Not in years. Not in months.

In weeks.

The men in the 3rd Armored Division called their M4 Shermans “Ronson lighters” because, like the cigarette lighter, they lit the first time they were hit. Against German Panthers and Tigers, their tanks were undergunned, underarmored, and powered by a fuel that turned any penetration into a fireball.

Unofficial doctrine became a sick joke:

It takes five Shermans to kill one Tiger. Expect to lose three of them doing it.

It was a suicide pact written in gasoline and steel and signed by logistics.

But every equation has an outlier. Every neat column of numbers hides a freak result, a statistical error that refuses to behave.

In the summer of 1944, that anomaly had a name.

Staff Sergeant Lafayette G. Pool.

In 81 days of near-continuous combat, this one man and his four-man crew destroyed 12 German tanks, 258 armored vehicles and self-propelled guns, and killed over 1,000 enemy soldiers. They led spearheads that cracked the German line. They moved so fast and hit so hard that German prisoners became convinced they were facing not just a tank commander, but an automatic, ghost-like killing machine.

This is the story of the man who turned a “tin can” into one of the deadliest weapons in the European theater.

This is the story of War Daddy.

The Boxer in the Dust

The man at the center of this storm did not start out in a turret.

He started in a ring.

Before the war, in the dust and heat of Texas, Lafayette Pool was a Golden Gloves boxing champion. He was not a technical dancer. He didn’t believe in fancy footwork or cautious jabs.

He believed in overwhelming violence.

His philosophy was brutally simple:

Hit first. Hit so hard the other man’s ancestors feel it. Make sure he never gets back up.

When he joined the Army in 1941, that philosophy was a problem.

The Army is a machine built on rules, manuals, formations, and procedures. It is designed to sand down edges, to turn individuals into units. It does not know what to do with men who are all sharp corners and forward motion.

Pool clashed with that machine immediately.

He hated drilling.

He hated parades and perfect salutes.

He hated waiting for orders while problems festered in front of him.

His natural leadership was obvious. He was offered a commission more than once.

Every time, he turned it down.

“I just want one of the best tank crews in the division,” he told his commanders.

“I don’t want a command tent. I want a turret.”

That decision sealed his fate.

It put him in the 3rd Armored Division—“Spearhead”. It put him at the point of the Allied advance.

And it put him inside the M4 Sherman.

That is where the story stops being a biography and becomes a survival horror.

A Coffin Called the Sherman

History likes to remember the Sherman tank as the hero of the war.

In one sense, that’s true. It was:

Reliable

Easy to maintain

Fast

And America built around 50,000 of them

But for the men inside, it was something else:

A steel coffin with a fuel tank.

By 1944, German armor technology had jumped a generation ahead.

A Panther’s frontal armor was almost immune to the standard American 75 mm gun. At 500 yards you could fire into its face and your round would do little more than scratch the paint.

The German long-barrel 75 mm on the Panther and the infamous 88 mm on the Tiger could punch through a Sherman from 2,000 yards away.

The Germans could kill you before you could even see them.

When a Sherman was hit, the result was often instant catastrophe:

Ammunition stored in the sponsons, right next to the crew

A high-octane gasoline engine

Spalling steel and sparks everywhere

One penetration, one tiny flare of ignition, and the inside of the tank became an incinerator in seconds.

This was the ring Lafayette Pool stepped into.

He was a heavyweight boxer facing giants—with one hand tied behind his back and his head painted bright red.

The math said he was already dead.

So he did what he’d always done when faced with a bigger opponent.

He refused to play by the rules.

Turning Weakness into a Weapon

Pool came up with an idea that bordered on insanity and went against everything in the field manuals.

If the Sherman tried to fight a long-range duel, it would lose. The math guaranteed it.

So he would never fight that way.

He looked at the tank’s flaws and twisted them into strengths.

The Sherman was weak, but it was fast.

Its turret traverse was quicker than German tanks.

It had decent reliability, which meant it could keep moving while others broke down.

Pool’s strategy was barbarically simple:

Close the distance.

“I’m not going to sneak around,” he told his superiors.

“I’m going to drive right down the throat of the German Army.”

It was a boxer’s mindset:

Get inside the other man’s reach. Smother him. Crowd him. Hit before he can think, let alone aim.

On paper, it looked like suicidal insanity.

In practice, it required one more ingredient.

A tank is not a machine. It’s a biological organism made of five men.

If the driver hesitates—you die.

If the loader fumbles—you die.

If the gunner blinks—you die.

If Pool was going to fight his way, he needed four men willing to live—and die—on his terms.

He found them.

Building the Biological Machine

Pool did not accept just any crew. He handpicked misfits who, on paper, looked like a disciplinary board’s nightmare.

In combat, they became something else: the most lethal tank crew in the U.S. Army.

The Driver: Wilbert “Baby” Richards

A quiet, unassuming kid from the Midwest. He looked like he should be bagging groceries, not driving thirty tons of steel.

But he had touch.

He could feel the engine, feel the tracks bite into the earth. He could make a Sherman dance when most men could barely make it lurch.

Pool needed a driver who, when ordered to charge a Tiger, wouldn’t flinch—who would floor the accelerator when every instinct screamed to hit the brakes.

Baby Richards was that man.

The Loader: Del “Jailbird” Boggs

The opposite of Baby.

Rough. Hard. A brawler with a criminal record. The Army had given him a choice: a cell or a uniform.

He chose the uniform and brought his anger with him.

The loader’s job is pure brutality:

Grabbing heavy steel shells, wrenching them into the breech, clearing the recoil path over and over while the tank bucks like a ship in a storm.

Boggs turned the 75 mm gun into something the Germans weren’t ready for—a near rapid-fire cannon.

He could load faster than anyone else in the division. Anger made his muscles run hot.

The Bow Gunner: Bert “Schoolboy” Close

Just a kid. Seventeen. He lied about his age to enlist.

He had the soft face of someone who should be worrying about prom, not Panzerfausts.

But behind the bow .30 caliber machine gun, he became a surgeon. His job was to cut down infantry, keep enemy soldiers from getting close enough to ram explosives into the tank’s weak spots.

He was the eyes and ears of the lower hull.

The Gunner: Willis “Groundhog” Oler

On the surface, Oler looked wrong for the job. Nervous. Jumpy. Dark circles under his eyes.

He seemed like a man on the verge of a breakdown.

But something changed when his eye pressed to the telescopic sight.

The shaking stopped.

He had predator vision. He could spot the glint of a helmet in a bush at 800 yards. He could thread a shell through a window from half a mile away while the tank was moving.

In tank warfare, whoever sees and fires first usually wins.

Groundhog Oler made sure that was them.

They painted a name on the side of their Sherman in big white letters:

IN THE MOOD

A boxer, a baby, a jailbird, a schoolboy, and a groundhog.

It wasn’t just a name.

It was a warning.

A Checkerboard of Death

They landed in France in June 1944, just after D-Day.

The beaches were secure.

The nightmare was inland.

If you’ve never seen the hedgerows of Normandy, it’s hard to understand what they did to tank warfare.

These weren’t garden hedges.

They were ancient earthen walls, six feet high, topped with dense, tangled brush and trees that had been growing for centuries. They divided the countryside into thousands of tiny, enclosed fields—green boxes with dirt walls and limited sightlines.

A checkerboard.

For tanks, a graveyard.

German tanks could sit behind a hedgerow, invisible.

When an American tank tried to clamber over, it exposed its vulnerable belly.

A single carefully aimed round into the thin floor armor could kill the entire crew.

The Germans had presighted intersections. Every gap in the hedges, every lane, every opening had been plotted and ranged in.

American crews advanced at a crawl, eyes straining at every bush, paralyzed by the invisible threat of the 88.

The Third Armored Division was stuck.

Lafayette Pool was not.

“Follow Me”

His first major engagement came near a French village called Villiers-Fossard.

American infantry were pinned down in muddy fields. German machine guns were chewing them apart. A Panzer unit was moving up to reinforce the line.

The sober, official manual answer was clear:

Call for artillery.

Wait for air support.

Try to flank.

Do not engage armored forces head-on.

Pool listened to the radio. He watched men hugging the earth, trapped under German fire.

Something inside him snapped.

He keyed his mic.

“Follow me.”

No flanking. No waiting.

He ordered Baby Richards to drive straight through the hedgerow.

IN THE MOOD exploded through the vegetation in a shower of dirt, wood, and roots, crashing into the open field beyond.

For a heartbeat, the battlefield froze.

The Germans were used to cautious Americans. Tanks that peeked around corners. Commanders buttoned up, afraid of snipers.

They had never seen a Sherman charge into the open, firing its main gun on the move like a fighter plane dive-bombing a target.

Pool stood in the commander’s hatch, exposed from the waist up.

This would become his trademark.

Others hid behind armor, peering through narrow periscopes.

Pool rode high, head out, a cigar clenched in his teeth, reading the battlefield with naked eyes.

“Gunner, infantry, two o’clock, hedge line!”

“Identified!” Oler snapped.

“Fire!”

The 75 mm roared.

German machine gun nests disappeared in geysers of earth and smoke.

“Driver, hard left! Keep moving, Baby! Don’t stop!”

The tank slewed sideways, mud spraying from the tracks. An anti-tank round screamed past, close enough that the shockwave stole Pool’s breath.

He did not duck.

“Loader, another up!”

“Up!” Boggs bellowed, slamming the breech shut.

Schoolboy raked the treeline with the bow gun, cutting down German infantry as they tried to retreat or get close.

Oler hunted targets as fast as Pool could call them.

Ten minutes later, the German strongpoint was gone.

Three armored vehicles destroyed. Infantry positions shredded. The line broken.

When the rest of the platoon finally rolled up, they found IN THE MOOD sitting in the middle of a smoking field, engine idling as if nothing extraordinary had happened.

The infantry climbed out of their foxholes and stared.

The rumor spread ahead of the column like ghost stories around a campfire.

There was a crazy Texan in the Third Armored.

A man who fought his tank like a boxer.

A man who, someone whispered, didn’t even know how to shift into reverse.

But baked into that legend was a fatal flaw.

Pool was fearless.

He was also reckless.

The Fatal Flaw

Officers lectured him. Friends warned him.

He wouldn’t listen.

He refused to button up his hatch, even under mortar fire, because he said he couldn’t smell the enemy through the periscope.

He drove his crew relentlessly. They rarely slept. When others rested, he was cleaning the gun, checking the engine, fussing over every bolt and bearing.

“We’re not here to survive the war,” he told his crew.

“We’re here to win it. And the only way to win is to kill them faster than they can kill us.”

Against infantry and light armor, that philosophy worked.

The real test was coming.

The big cats were waiting.

Staring Down the Big Cats

As Operation Cobra cracked open the hedgerows and the breakout began, the Third Armored Division was unleashed into open country.

No more hedgerow crawling.

Now it was speed and open roads.

Pool demanded the same thing from his officers that he’d demanded from his crew.

The point.

He insisted on leading.

Being the point tank is a death sentence. You are the tripwire. The first thing the enemy sees. The first thing the anti-tank gunners dial in.

Pool claimed he could spot ambushes before they triggered.

Terrifyingly often, he was right.

He could see the unnatural regularity of cut branches hiding a gun. The glint of glass from a scope in a treeline.

One afternoon near Saint-Lô, the division ran into a German blocking force—a mix of Panzer IVs and self-propelled guns.

The column hesitated.

Pool did not.

He roared past the lead tanks.

“Get out of the way,” he barked over the radio.

“IN THE MOOD up front.”

A Panzer stepped out from behind a farmhouse at 400 yards, its long gun swinging toward them.

In that fraction of a second, life and death came down to reflex.

“Baby, break!”

Richards slammed the brakes.

Thirty tons of steel skidded, tracks locking, nose dipping.

The German round screamed past the front of the hull, missing by inches.

Oler was already on target.

“Target front tank—fire!”

The Sherman kicked back. The armor-piercing round hit the Panzer at the seam between turret and hull.

Sparks. Smoke. Then a plume of black fire.

“Next target!”

Pool didn’t watch it burn. He was already hunting the next threat—halftracks trying to flee, anti-tank guns traversing too slowly.

By the end of the engagement, they had destroyed more vehicles in one afternoon than most platoons did in a month.

But aggression has a price.

The tank was being flogged like a stolen horse. The engine overheated. Tracks wore thin. The crew ran on caffeine, cigarettes, and adrenaline.

Jailbird Boggs would later say:

“We were all crazy. You had to be. If you stopped to think about what we were doing, you’d jump out and run back to Texas.

War Daddy kept us going. You didn’t want to let him down.”

And while they punished the machine, the enemy was learning.

The Germans began to notice a pattern.

One particular Sherman—the one with IN THE MOOD painted on the side—spelled disaster whenever it appeared.

They started targeting it specifically.

Captured prisoners asked to see “the American ace.” Some swore the Americans had built a new kind of tank, one that could fire faster than any machine they had seen.

They didn’t understand the truth.

There was no automatic tank.

There was only Dell Boggs sweating in the gloom, hands bleeding as he slammed shell after shell into the breech; only Willis Oler’s steady eye; only Baby Richards’ foot welded to the floor; only a commander who refused to slow down.

The Ghost Tank

By August, the legend of Lafayette Pool reached the ears of General Maurice Rose, the division commander.

Rose was not fond of mavericks. He hated showboats and cowboys.

But he was also a pragmatist.

Wherever Pool went, the map changed. Lines that had been static for days suddenly jumped forward. German units that were supposed to hold “at all costs” dissolved under the onslaught.

Rose summoned him.

Pool arrived filthy, unshaven, smelling of sweat, cordite, and burnt oil. He expected a reprimand. Maybe a court-martial for reckless disregard of orders.

Instead, Rose asked quietly:

“Sergeant, how many vehicles have you destroyed this week?”

Pool shrugged.

“Stopped counting, General. A few.”

Rose flipped through reports.

“They say you cleared the entire sector north of the river by yourself.”

Pool shook his head.

“Had my crew, sir.”

Rose studied him.

“You’re doing good work, Pool. But you’re taking too many risks. You’re going to get yourself killed.”

There was a pause.

Then Pool said the line that explains everything that came after:

“General, I’m already dead.

The only question is how many of them I take with me before I stop breathing.”

He understood the math.

He knew the Sherman was a death trap.

He knew statistically IN THE MOOD was living on borrowed time, that every engagement was a coin toss.

He just didn’t care anymore.

If death was inevitable, he had no reason to slow down.

He had every reason to go faster.

Playing Chicken with a Tiger

As the Third Armored pushed toward the Falaise Gap, the German Army was in full retreat—but retreating enemies are often the most dangerous.

They were cornered. And cornered animals bite.

Intelligence warned of heavy armor near a town called Fromentel.

Tigers.

The Tiger was the boogeyman of every American tank crew:

Sixty tons

A devastating 88 mm gun

A hundred millimeters of frontal armor

From the front, a Sherman’s 75 mm might as well be throwing rocks.

To kill a Tiger, you had to do the impossible:

Get close. Get around its flank. Live long enough to fire into its side or rear.

The safe answer was to avoid it, call in air support—or pray.

Pool did none of those things.

IN THE MOOD led the column down a narrow, tree-lined road. A perfect kill zone.

The radio crackled:

“Tiger, Tiger—front!”

A massive silhouette materialized ahead, the long barrel of the 88 swinging toward them, blocking the road like a moving bunker.

This was where the math said, You lose.

Pool did something no Tiger commander expected to see from a “cowardly Sherman”.

He attacked.

“Charge him! Ram him if you have to!”

Baby Richards slammed the accelerator down.

The Sherman roared forward, straining, gathering speed.

German gunners were used to stationary or reversing targets.

They were not ready for a thirty-ton projectile rushing them at twenty-plus miles an hour.

The Tiger’s turret traverse was powerful—but slow.

IN THE MOOD closed the distance.

800 yards.

600.

400.

The Tiger fired.

The 88 mm round tore past, close enough to shatter glass and rattle bones.

Pool’s voice was calm:

“Hold your fire… hold…”

He knew a shot at the Tiger’s face would bounce. He needed a weak spot.

At 200 yards, the Tiger filled the sight like the side of a barn.

“Tracks.”

Oler fired.

The Sherman bucked.

The round smashed into the Tiger’s track. Steel shattered. The heavy beast lurched, spinning on its broken tread, exposing its thinner side armor.

“Now the flank. Kill him.”

Oler fired again.

And again.

Two shells slammed into the exposed side plate.

For a heartbeat, nothing.

Then the Tiger’s ammunition cooked off.

A blast ripped the turret from the hull. The 60-ton tank died in a geyser of flame.

IN THE MOOD roared past, so close the paint on her flank blistered from the heat.

They had done what the manuals said you didn’t do.

They had played chicken with a Tiger and lived.

Afterward, Pool slumped back into the hatch, hands shaking—not from fear, but from the toxic cocktail of adrenaline and exhaustion.

“You okay, Daddy?” Richards asked.

Pool lit a cigar with unsteady fingers.

“Keep driving, Baby,” he said.

“There’s more of them ahead.”

It was the end of the beginning.

They had survived Normandy. Survived the breakout.

They had painted such a big target on themselves that the entire German Army was now aiming for the Sherman with the white lettering on the side.

Burning Through Tanks and Men

The first IN THE MOOD didn’t survive the summer.

A hit. Fire. Smoke.

They scrambled out of the burning hull, coughing, eyes streaming.

Most men, after escaping a burning tank, begged for a transfer. Any job that didn’t involve sitting on top of ammunition inside a rolling gasoline drum.

Pool walked to the motor pool and demanded another tank.

Immediately.

They gave him an upgrade: the M4A1(76).

From the outside, it looked like another Sherman.

To War Daddy, it was a heavier glove.

A longer barrel

A high-velocity 76 mm shell

Finally, a gun that could punch through a Panzer IV at combat ranges and pose a real threat to heavier armor from the flank

Pool patted the cold steel.

“Now we can really hurt them,” he told Boggs.

With the new gun came a darker intensity.

The rampage entered its most violent chapter.

Reports began filtering up German chains of command of a ghost tank:

A single Sherman that appeared on the flanks

Tore through supply columns

Shattered rear guards

And vanished before anti-tank guns could lock on

They didn’t know it was a boxer from Texas and four exhausted men.

They just knew that in certain sectors, if you saw an American tank with white letters on the hull, you were already dead.

Pool’s aggression became contagious.

Tanks behind him charged because he charged.

Infantry advanced because they saw IN THE MOOD shrug off incoming fire.

The whole division seemed to move faster when he was on point.

But inside the steel box, the biological machine was starting to break.

You cannot fight at that tempo for 81 days without consequences.

Baby Richards drove on instinct and caffeine, hallucinating from sleep deprivation. He later admitted that roads sometimes turned into rivers or snakes in his vision—he kept going because War Daddy told him to.

Schoolboy Close stopped looking like a teenager. His face became a permanent mask of grease and soot. His eyes went hollow. He had cut down too many men with the bow gun to pretend he was just a kid anymore.

And Pool?

Pool was coming apart.

He stopped sleeping almost entirely.

He developed a nervous tic.

He ground his teeth until he chipped them.

He refused to leave the turret.

His insistence on riding half-exposed became an obsession.

“Periscopes are coffins,” he said.

“If I’m buttoned up, I’m blind. If I’m blind, we die.”

So he made himself into the tallest silhouette on the battlefield:

Six feet of Texan, standing in the hatch in rain, dust, and shrapnel, daring the enemy to shoot him.

At Colombier, that dare nearly killed them all.

At dusk, flanking a town through dense woods, a hidden German dual-purpose flak gun opened up.

Green tracers stitched the air around the turret. One clipped the commander’s hatch, showering Pool’s face with sparks and steel.

“Reverse! Reverse!” he screamed.

Baby Richards froze.

For a moment, IN THE MOOD was a statue.

Engine stalled. No cover. A sitting duck in the middle of a fire lane.

The flak gun’s barrel swung for a kill shot.

Pool didn’t drop into the turret. He didn’t hide.

He grabbed the roof-mounted .50 caliber.

He stood fully exposed and opened fire on the barn he believed was hiding the gun.

It was madness. A man with a machine gun vs an anti-tank cannon.

But the heavy tracers punched through wood and hay, spraying splinters, starting fires, blinding the gun crew with smoke and shock.

“Start the damn tank, Baby!” Pool roared, never easing off the trigger.

The engine coughed, caught, roared.

Richards threw it into gear. IN THE MOOD lurched backward into the trees just as a high-velocity round obliterated the space where they’d been seconds before.

They sat in the dark, engine idling, lungs burning.

Groundhog was shaking. Jailbird was praying out loud.

Pool dropped into the turret, face bleeding from shrapnel, eyes bright with something halfway between insanity and clarity.

He lit a cigar.

“We know where they are now,” he whispered.

“Go back out there. Flank left. Kill them.”

And they did.

They flanked the barn. Oler put a 76 mm round through the doors. The flak gun and its crew ceased to exist.

That was the War Daddy effect.

He took men paralyzed by terror and replaced their fear of death with something stronger.

Fear of disappointing him.

When the Coin Comes Up Tails

By mid-September, the numbers were staggering.

258 enemy vehicles destroyed

12 tanks

3 different Shermans shot out from under them

Around 250 prisoners captured

Those are not platoon numbers. Those are battalion-level numbers achieved by one crew.

But the law of averages is not impressed by courage.

Flip a coin and you can get heads ten times in a row. Maybe twenty.

Eventually, tails comes up.

The Third Armored reached the German border.

The Siegfried Line. Dragon’s teeth. Concrete, steel, and mined hills.

France had been a war of movement.

Germany would be a war of attrition.

The terrain changed. Steeper hills. Narrower roads. Tighter towns. The enemy was no longer covering ground for time. They were defending home.

On the morning of September 19, 1944, near the town of Stolberg, a strange mood settled over the crew.

They were bone-deep tired.

The sky was low and gray. Engine noise seemed to carry for miles.

Pool was quieter than usual.

He told another soldier that morning:

“I’m on my last tank.”

It wasn’t a complaint. It was a premonition.

He told General Rose:

“I’ve got a bad feeling, General. The bell is tolling.”

Rose offered him a way out.

“Pool, you’ve done enough. Go home. Sell war bonds. Train new crews. You’re a hero.”

Pool shook his head.

“I can’t leave my boys. If I leave, they die. I take them in, I take them out.”

He climbed into IN THE MOOD one last time.

The mission: flank Stolberg and cut off German retreat routes.

The Germans were ready.

They’d studied these aggressive American columns. They’d built a trap for the point tank that always seemed to charge hardest.

They positioned a Panther behind a concrete wall, its long 75 mm gun covering the only intersection that mattered.

It was a kill box.

IN THE MOOD drove straight into it.

Speed had been life on open ground.

In a cramped German town, speed became blindness.

Pool stood in the hatch, scanning windows and rooftops.

But he couldn’t see around corners.

Baby Richards pushed for the intersection. Groundhog swept the turret left and right. Jailbird sat with an armor-piercing shell already in the breech, palm resting on the safety rail.

They were operating at peak efficiency.

They turned the corner.

At 5:00 p.m., the world ended.

Pool saw a black circle.

The muzzle of a Panther gun, less than a hundred yards away.

Point-blank.

No time for tricks. No flanking. No boxing footwork. Just math and steel.

“Back up!” Pool screamed, voice tearing.

“Baby, back up!”

Richards stomped the brakes.

The Sherman skidded on the cobblestones, sparks flying from locked tracks.

The German gunner didn’t need to aim.

He’d dialed in that intersection hours ago.

He fired.

The shell hit the ground just beside the tracks.

The explosion picked up a thirty-ton tank like it was a toy, hurled it sideways, and dumped it into a ditch on its side.

Inside, everything became shrapnel.

Men slammed into armor. Ammo boxes tore loose. Bodies and steel collided.

Boggs went unconscious. Schoolboy’s nose burst. Oler saw stars.

Pool was thrown halfway out of the commander’s hatch, dazed, ears ringing, lungs full of smoke.

He tried to move.

The Panther commander saw the Sherman disabled but not dead.

He ordered a second shot.

This time, the round hit the turret.

The impact was biblical.

Shards of metal scythed through the air at supersonic speed.

One of them found the only unarmored part of Lafayette Pool:

His leg.

He looked down.

The dust was still settling. His ears were still screaming.

He tried to stand and couldn’t.

His brain processed what his eyes were seeing.

The limb was simply… gone.

Bright arterial blood pulsed onto German dirt.

For the first time in 81 days, War Daddy was not barking orders.

He was silent.

If the German crew thought the fight was over, they didn’t understand the men they were facing.

Jailbird Boggs came to, shook off the ringing, and realized what had happened.

He didn’t run.

He climbed out of the overturned hull under sniper fire, scrambled up to the hatch, and dragged Pool’s bleeding body free.

Schoolboy Close grabbed the medical kit. They were not soldiers following a manual anymore.

They were sons trying to save their father.

They hauled him into a foxhole. The Panther still prowled the intersection, searching for another shot.

They slapped on a tourniquet. Injected morphine. Held pressure. Cursed. Prayed.

Pool’s face was white.

He looked up at his crew.

His boys.

He could have asked for a chaplain. For his wife. For his mother.

He grabbed Baby Richards by the collar and rasped his final combat order:

“Somebody take care of my tank.”

Minutes later, reinforcements arrived. Medics loaded Pool onto a jeep.

As they drove him away, he twisted to look back.

He saw IN THE MOOD on her side in a ditch, smoke curling from the turret.

The 81-day rampage was over.

The ace was out of the deck.

The Hardest Round

Doctors at the field hospital took one look at the leg and made the only choice they had.

They amputated high above the knee.

When Lafayette Pool woke up, the war in Europe raged on.

His war was over.

He was twenty-five years old.

One leg.

A chest full of medals.

And a future that looked like an empty road.

Most histories end here.

They tell you he got a prosthetic, settled down, lived happily ever after.

That’s the sanitized lie.

The truth is uglier.

Pool was a physical man. His identity was built on:

His fists

His body

His ability to lead from the front and never back down

Now he was disabled.

The Army discharged him in June 1946.

They gave him a pension and a handshake.

“Thank you for your service. We don’t need one-legged tank commanders.”

He went home to Texas.

He opened a gas station. Tried to be a civilian. Tried to be a husband, a neighbor, an ordinary man.

The silence of peace was deafening.

He missed the noise. The purpose. The feeling of four men trusting him with their lives.

Most of all, he missed the crew.

He carried a private conviction like shrapnel next to the heart:

That he’d abandoned them in that ditch at Stolberg.

The math said his military career was over.

Regulations were clear: amputees do not serve in combat roles.

Math had never stopped him before.

Charging the Regulations

Pool did what he always did when faced with impossible odds.

He attacked.

He began a one-man campaign to return to service.

Letters.

Visits.

Arguments.

Appeals to generals.

He used his fame as an ace, but not as a trophy.

As a weapon.

He argued the obvious:

“My brain isn’t in my leg.

A tank commander doesn’t need to run. He needs to think. He needs to lead. He needs to fight.”

In 1948, the Army blinked.

In a rare exception, they let Lafayette Pool reenlist.

He became one of the only World War II combat amputees allowed back into active duty.

They didn’t park him behind a desk.

They sent him to Fort Knox, to the Armored School.

They made him an instructor.

Imagine being a young recruit in 1950, climbing into a training tank—and your instructor is a giant Texan with a heavy limp, a chest full of silver stars and Purple Hearts, and a reputation whispered about in mess halls.

He taught from scars, not slides.

He told them:

The manual is a guide, not a Bible.

Speed is armor.

Aggression saves lives.

Sometimes he would tap his prosthetic leg with his cane and say:

“This is what happens when you hesitate.

Don’t hesitate.”

He stayed in uniform until 1960, eventually retiring as a Chief Warrant Officer.

He watched tanks change: Sherman to Pershing to Patton. Guns got bigger. Armor thicker. Engines stronger.

He never changed his core belief:

“The machine doesn’t matter.

It’s the five men inside who decide who lives and who dies.”

Four Reasons a Tin Can Beat a Tiger

When we look back at the raw numbers—81 days, 258 vehicles, 12 tanks, over 1,000 enemy soldiers—it feels impossible.

Like someone rewrote the laws of physics.

Historians and analysts have spent decades trying to reverse-engineer his success.

Strip away the legend and four factors remain.

Factor 1: The Biological Machine

Most tank crews were five individuals doing five jobs.

Pool’s crew was a hive mind.

They stayed together. They refused promotions that would split them up.

They anticipated one another.

Baby didn’t always need an order to brake or accelerate; he could feel the rhythm of the fight through Pool’s voice.

Jailbird didn’t always need a call for HE or AP; he guessed the next target and loaded ahead.

Groundhog started traversing before Pool finished the sentence.

This shaved seconds off their reactions.

In tank duels, seconds are lifetimes.

Their synchronization was an advantage you couldn’t write into specs or bolt onto armor.

Factor 2: Turning a Fatal Flaw into a Tactic

Pool’s recklessness—his refusal to use cover conventionally, his insistence on charging—did something strange to German commanders.

It broke their OODA loop: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act.

They were trained to fight cautious opponents:

Tanks that peek out

Reverse under fire

Call for artillery

Try to flank

They were not trained for a Sherman charging at 30 mph across open ground, firing on the move, its commander standing in the hatch like he was immortal.

It looked wrong.

It felt like bait.

So they hesitated.

They tried to understand instead of just react.

In that sliver of confusion, Pool closed distance and killed them.

He weaponized his own insanity.

Factor 3: The Eyes of the Groundhog

No matter how aggressive the doctrine, warfare often comes down to one thing:

Who sees whom first.

Willis “Groundhog” Oler’s vision was a superpower.

But vision alone isn’t enough.

Pool trusted him completely.

If Groundhog said “tank, left,” Pool didn’t demand a location, a range, a map reference.

He yelled, “Traverse left—fire.”

That trust erased the delay between spotting and shooting.

In those tiny slices of time, victory lives.

Factor 4: The Acceptance of Death

This is the darkest and most uncomfortable factor.

Most soldiers are trying—sensibly—to survive.

They cling to life. They avoid unnecessary risk. They favor caution.

Lafayette Pool accepted that he was already dead.

He told his division commander as much.

Once you take the fear of death off the table, a terrible freedom opens up.

You’re willing to:

Push the tank to mechanical breaking point

Take angles no one else dares

Stand in a hatch under shellfire because the visibility advantage is worth the bullet risk

That fatalism made him the most dangerous man on the battlefield.

Spirit Inside the Steel

Lafayette Pool died in his sleep on May 30, 1991, at seventy-one years old, in Texas—not far from the base where he’d taught so many young tankers.

At his funeral, they talked about medals.

But more than that, they talked about a man who refused to stay down.

The boxer who took every punch the war had to offer:

Losing his leg

Losing his tank

Losing his war

And still got back up to answer the next bell.

If you go to the Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor at Fort Knox, you won’t see the original IN THE MOOD.

She’s still in that German ditch, rusted into the soil.

But you can see the legacy.

You can trace it in:

Training manuals rewritten after 1945

Doctrine that emphasized speed, aggression, crew cohesion, initiative

For 81 days in 1944, Lafayette Pool and his four men proved something the numbers had said was impossible.

The Sherman was too tall. Too thin. Too flammable.

But it wasn’t the steel that mattered.

It was the spirit inside the steel.

They proved that a Ronson lighter could help burn down the Reich—if you had the courage to strike the match.

The math said they should have died in week one.

The math said a Sherman can’t kill a Tiger.

The math said an amputee can’t be a tank commander.

Lafayette Pool spent his life proving that math is just a suggestion.

The story of War Daddy is not just about destroying tanks.

It’s about a refusal to accept the odds as destiny.

It’s about looking at a suicide mission and deciding that if you’re going out, you’re going out swinging.

News

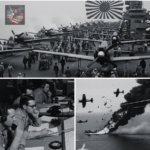

Japan Was Shocked When 400 Planes Vanished in a Single Day

THE DAY THE SKY BROKE How 400 Japanese planes vanished in a single afternoon—and how one American fighter turned the…

How a 12-Year-Old Boy’s Crazy Eyeglass Trick Destroyed 3 Nazi Trains in Just 7 Seconds

The Boy Who Burned the Reich How a malnourished 12-year-old with a piece of broken glass became the most impossible…

How a US Soldier’s ‘Reload Trick’ Killed 40 Japanese in 36 Minutes and Saved 190 Brothers in Arms

The Hunter Who Held the Line at Dingalan Bay How a 24-year-old Georgia woodsman stood alone against 100 attackers—and saved…

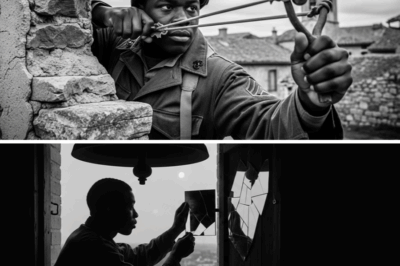

How an 18-Year-Old Black US Marine’s Slingshot Took Out a German Sniper From 200 Yards

The Kid With the Slingshot Who Broke the German Line How an 18-year-old Marine from rural Georgia used a childhood…

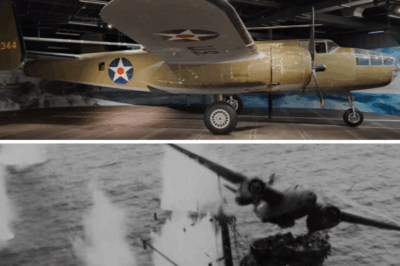

Engineers Called His B-25 Gunship “Impossible” — Until It Sank 12 Japanese Ships in 3 Days

7:42 A.M. — A Man, A Burning Sky, And an Idea Too Crazy to Live At 7:42 a.m. on August…

My Son Took All Our Savings And Vanished—25 Years Later His Daughter Showed Up With a Key He Left Me

PART 1 — The Girl at My Door The doorbell rang at 9:47 a.m. It startled me hard enough that…

End of content

No more pages to load