March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, roughly 400 miles south of Iceland.

Convoy HX 229 forces its way through 15-foot winter swells, forty-one merchant ships dragging 140,000 tons of food, fuel, and war material toward a starving Britain. In the cramped galley of the Liberty ship SS William Eustace, 28-year-old cook Thomas “Tommy” Lawson braces himself against the roll as he scrubs dishes, feeling the hull shudder under each wave.

Up on the bridge, Captain James Bannerman scans the grey horizon through binoculars. He knows exactly what’s out there. Beneath the surface, somewhere in the black water, the U-boats are listening.

Six hundred yards off the convoy’s port beam, in the control room of U-758, Kapitänleutnant Helmut Manseck leans over his plotting table. His hydrophone operator presses headphones tighter to his ears, blocking everything but the sea’s whisper.

“Kontakt, Peilung 280,” he murmurs. “Multiple screws. Heavy machinery. Estimate… forty ships.”

Manseck smiles. The wolfpack has found its prey.

What none of them knows—not Bannerman, not Manseck—is that the quiet, anonymous cook down in the Eustace’s galley has stumbled onto something strange about how Liberty ships sound underwater. Something that, within months, will help turn the entire Battle of the Atlantic.

Over the next six days, convoys HX 229 and SC 122 will be mauled. Twenty-two merchantmen will go down with 300 seamen, the worst convoy disaster since 1942. In that same month, March 1943, U-boats will sink 567,000 tons of Allied shipping—more than in any other month of the war. At that rate, Britain has food for roughly three more months. Winston Churchill will later write that the only thing that truly frightened him in the war was “the U-boat peril.”

The reason is simple: the Germans can hear almost everything. Their hydrophones—passive underwater microphones—are brutally effective. A wolfpack can pick up the propeller noise of a big convoy from 80 nautical miles away. An individual freighter can betray her presence from up to 12 miles. Cavitating propellers, humming engines, hull vibrations—they all combine into unique underwater signatures that might as well be radio beacons for torpedoes.

Allied escorts try everything. Zig-zag courses. Radio silence. Constant ASDIC (sonar) sweeps. It isn’t enough. The ocean is a superb carrier of sound, and the convoys are simply too loud. U-boats hunting in packs can sit quietly at 400 feet, listen, and choose their firing positions with almost no risk.

In Liverpool, at Western Approaches Command, people with impressive titles and long résumés have been wrestling with this problem for years. In 1941, the Royal Navy fitted all escorts with ASDIC sonar—great for detecting a submerged submarine directly ahead at 2,500 yards. But the Germans quickly learn to attack from the beam or stern, outside the sonar cone, and to strike surfaced at night, where ASDIC is useless.

In 1942, scientists at the Admiralty Research Laboratory develop high-frequency direction finding—“Huff-Duff”—to locate U-boats by their radio transmissions. It works brilliantly, until the wolfpacks close in on a convoy. Then they stop talking. Once they have contact, they don’t need radios. They just listen. The submarines fall silent—and the convoys keep broadcasting their location with every turn of a noisy propeller.

By early 1943, the Admiralty has spent the equivalent of more than half a billion dollars today trying to solve the noise problem. Professor Patrick Blackett, head of naval operational research, writes a classified report spelling it out: merchant ship propeller cavitation and machinery resonance produce sound profiles detectable at extreme ranges. Without rebuilding ships from the keel up—something impossible in wartime—the convoys will keep announcing themselves to enemy hydrophones.

Dr. Harold Burruss, the Admiralty’s chief naval architect, explains the physics in a memo. A Liberty ship’s propeller, 15 feet in diameter, turns at 76 RPM under load, throwing over 200,000 tons of water per hour astern. Cavitation bubbles form and collapse on the blades, creating broadband acoustic energy across 100–1,000 Hz—exactly the band where German hydrophones are most sensitive. To fix it, he argues, you’d need a completely redesigned propulsion system and months in dry dock for each ship. There’s no time, no steel, and no dock space for that.

At a convoy conference in London on March 4th, Rear Admiral Leonard Murray of the Royal Canadian Navy gives it to the room straight:

“Gentlemen, we’re losing. Our escorts can’t hear the U-boats over our own convoy noise. The enemy can hear us from fifty miles away. Unless we solve the acoustic detection problem, we lose the Atlantic by summer.”

Ideas pour in. None are practical. Mount every machine on sound-damping bases? It would cost a quarter million dollars per ship and keep it in dock for twelve weeks. At 2,400 convoy ships, you’d be done sometime in the next century. Coat hulls in rubber? Trials show it rots quickly in salt water, adds drag, and slows ships by three knots—making them easier targets. Retool propellers with swept blades to reduce cavitation? Excellent theory, but hundreds of foundries would have to change their entire production lines while fourteen thousand existing screws are scrapped.

By March 15th, the experts have reached a grim consensus: there is no technical fix, not in time. Shipping will go on sounding like dinner bells to every U-boat in earshot. The only answer is more escorts, more aircraft, more guns—and hope enough hulls get through to keep Britain alive.

Eight hundred miles away, in the storm-tossed North Atlantic, a merchant cook is about to prove them all wrong.

Thomas Patrick Lawson doesn’t look like anyone’s idea of a naval innovator. Born in South Boston in 1915, he left school at fourteen during the Depression to support his family. He flipped eggs in a diner, then shipped out as a galley hand on coastal freighters. When war came, he joined the U.S. Merchant Marine not out of patriotism, but because the pay—$125 a month—was three times what he earned at home. His captain’s evaluation in June 1942 reads: “Lawson, T.P. Ship’s cook. Adequate performance. No leadership potential. Recommended for galley duties only.”

No one expects genius from the man who makes breakfast.

After the William Eustace survives three convoy trips to Liverpool, Lawson develops a strange habit. On his off-watch hours, he goes down into the engine room and just… listens. The others think he’s mad. “Tommy’s going to cook himself in there,” grumbles First Mate Robert Chen. “That place is louder than hell and twice as hot.” But Lawson isn’t there for comfort. He’s there because something about the noise bothers him.

On February 19th, 1943, in mid-Atlantic with convoy SC 118, a torpedo hits a ship two columns over. There’s the distant thump of the explosion—then Lawson hears something else through the steel: a long, hollow booming, as water tears into the other ship’s hull.

And then… nothing.

The sound of that ship simply vanishes.

Back in the engine room, the chief engineer, a rough Scotsman named Donald McLeod, is shouting orders. Lawson grabs his arm.

“When the water came in… it stopped the noise,” he says.

“Of course it stopped,” McLeod snaps. “She’s full of water. She’s dying.”

“No,” Lawson insists. “I mean the sound. The vibrations. The U-boats couldn’t hear her anymore.”

McLeod gives him a look like he’s lost his mind. “So what?”

“So what if we could flood parts of our ship on purpose?” Lawson pushes. “Not enough to sink us. Just enough to muffle the machinery noise.”

McLeod’s expression shifts from confusion to irritation. “That’s the daftest thing I’ve heard this week. Get back to your galley.”

Lawson does as he’s told—but he doesn’t let the idea go. For two weeks, he scratches diagrams in a notebook. Water-filled chambers around the propeller shaft. Ballast tanks hugging the machinery. Controlled flooding systems. He shows his sketches to McLeod, who waves him off. He shows them to the first mate, who laughs. He shows them to Captain Bannerman, who sighs and tells him, kindly, to leave engineering to engineers.

Nobody listens to the cook.

On March 24th, the William Eustace docks in Liverpool. Lawson has 48 hours shore leave. Instead of heading for a pub, he walks to Derby House—Western Approaches Command headquarters—and tells the sentries he needs to speak to an admiral about U-boats.

He doesn’t get an admiral. He gets grabbed by the shore patrol.

“You can’t be in here, mate,” one of the Royal Navy policemen says, taking his arm. “Restricted area.”

“I’ve got something about convoy noise,” Lawson insists. “I have an idea.”

“Everyone’s got ideas,” the other scoffs. “Off you go.”

They’re marching him toward the door when a voice cuts across the lobby.

“Wait.”

The man who spoke is Commander Peter Gretton, twenty-nine years old, already a veteran escort commander. He has just come back from convoy ONS 5, where he lost thirteen merchantmen to wolfpacks. He is tired, angry, and desperate.

“What did you say about convoy noise?” he asks.

Lawson explains what he heard when the torpedoed ship flooded, his guess about water damping vibration, his concept of water-filled spaces acting as acoustic insulation. Gretton listens, arms folded, eyes narrow.

“That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve heard this month,” he says at last. “Water inside a ship is usually called sinking.”

“Not if you control it,” Lawson replies. “Small chambers. Around the shaft. Against the engine mounts. You don’t flood the ship, you use water as a sound barrier.”

Gretton is about to dismiss him, then stops.

“Say that again,” he says slowly.

“Water absorbs vibration better than air. If you put it in the right place, between the machinery and the hull, you stop the sound from reaching the sea.”

“I know what acoustic insulation is,” Gretton snaps reflexively. Then his tone softens. “Come with me.”

The next day, March 25th, at the Liverpool dockyard, Gretton brings Lawson aboard the corvette HMS Sunflower, now in dry dock. The ship’s engineer, Lieutenant James Whitby, joins them. Gretton’s plan is simple: if this madness is going to be tried, they’ll try it on a small warship, quietly. No Admiralty committees. No memos.

Over three long days, the odd trio cobble together a prototype. They weld old oil drums around the corvette’s propeller shaft housing and fill them with seawater. They stack sandbags around the engine mounts to mimic the effect of water mass. It is crude, ugly, and in direct violation of a library’s worth of regulations.

On March 28th, Sunflower creeps out into the Mersey at low speed. The submarine HMS Trespasser, in on the secret, submerges 500 yards away, hydrophones on. Lawson stands on deck, heart pounding.

When Trespasser surfaces, her captain signals: “Heard you clearly. Engine noise, propeller cavitation. No change.”

Failure.

“Told you it was bloody stupid,” Whitby mutters.

But Lawson has noticed something. “We filled those drums in dry dock,” he says slowly. “They’ve been leaking. They’re not full anymore.” They had been testing half-empty chambers. The water wasn’t forming a proper barrier.

Gretton rubs his face. “If the Admiralty finds out I’m modifying a warship without orders, I’ll be court-martialed.”

“If the Admiralty finds out U-boats are sinking twenty ships a week because we’re too proud to test a cook’s idea,” Lawson replies quietly, “we lose the war.”

Gretton stares at him for a long moment. Then he says, “Three more days. Then we stop.”

They work around the clock. This time, they weld proper sealed steel cans around the shaft housing. They rig rubber bladders filled with water against the engine mounts. They build, without knowing the future name for it, the first crude “liquid acoustic damping” system.

On April 2nd, they try again. Sunflower runs at full speed. Trespasser dives to 1,000 yards and listens.

Nothing.

At 400 yards, the hydrophones still can’t pick up the corvette’s noise against the background of the sea. Only when the distance closes further does a faint signature appear. Before the modification, Sunflower had been clearly audible at more than ten miles.

Gretton goes pale. Lawson’s hands shake.

It works.

On April 3rd, in London, Commander Gretton stands in a boardroom facing Rear Admiral Max Horton, the hard, sharp commander-in-chief of Western Approaches, along with senior staff and Dr. Burruss—the same architect who insisted the problem was insoluble. Beside Gretton stands Lawson, very aware that he is a 28-year-old American cook in front of some of the most powerful naval officers in Britain.

Gretton presents the result: hydrophone detection range reduced from roughly 12 miles to about 400 yards—a 97 percent reduction in acoustic signature.

The room erupts. Burruss calls it preposterous: unauthorized changes to a Royal Navy vessel based on the suggestion of “a cook.” Rushbrooke, the director of naval intelligence, calls Gretton reckless.

Gretton fires back. What, exactly, is being compromised? The current “system” of letting U-boats hear convoys from fifty miles away?

Horton raises a hand.

“Explain it simply,” he tells Lawson.

“Sir,” Lawson says, steadying himself, “the ship’s machinery vibrates. Right now, that vibration goes straight through the hull into the water. The water carries the sound for miles. If you put water into sealed chambers around the propeller shaft and near the engines—between the machinery and the hull—it soaks up some of that vibration before it reaches the sea. It doesn’t flood the ship. It just blocks the sound.”

Burruss protests that water inside structure creates stability issues, corrosion, weight problems. Lawson calmly points out that we’re talking about sealed chambers, designed for that purpose, not open flooding. And they’ve already tested it.

“One test,” Burruss scoffs. “In a river. With a friendly submarine. Hardly definitive.”

Horton ignores the tone. “What would it take to retrofit a convoy?” he asks.

Rushbrooke is appalled. The dockyards are overloaded. Steel is precious. Retrofitting thousands of ships for an unproven scheme is madness. Gretton counters with harder numbers: in March, more than half a million tons of shipping went down because the enemy heard them coming, and U-boat losses were moderate. If nothing changes, they could lose the war at sea by autumn.

Burruss argues that even if the idea has merit, doing it on a grand scale is impossible. Too many ships, no time.

Lawson quietly cuts through the argument. The prototype on Sunflower took three days. The work isn’t exotic. Weld sealed cans around things that vibrate. Fill them with water. Any reasonably trained dockyard crew can do it. Any ship’s engineer can maintain it. And you don’t have to start with the entire fleet—just a handful of ships in one convoy to see what happens under real attack conditions.

Horton walks to the window, looking out at the Thames. When he turns back, he has made his decision.

“Commander Gretton,” he says, “you will retrofit six merchant ships in convoy ON 184, sailing from Liverpool in eight days. Mr. Lawson will supervise and train the engineers. Dr. Burruss, you will assist, even if you think it insane. If it works, we apply it fleet-wide. If it fails…” He lets the sentence hang. “You will spend the rest of the war sweeping mines in the Orkneys. Clear?”

“Crystal, sir,” Gretton answers.

Horton looks at Lawson. “Mr. Lawson, I don’t know if you’re a genius or a madman. But we are desperate. Don’t make me regret this.”

“I won’t, sir,” Lawson says, hoping he’s right.

In the following week, at Liverpool dockyards, six ships—SS Daniel Webster, SS James Herrod, SS John Davenport, SS Samuel Elliott, SS Benjamin Key, and William Eustace—receive the strange new fittings. Crews weld 24-inch steel cylinders around the propeller shaft housings and fill them with seawater. They add water-filled rubber bladders around main engine mounts and steam lines. The system is ugly and improvised. Each installation adds about 18 tons of weight and takes roughly 64 hours per ship.

Naval engineers shake their heads. It looks, one remarks, like someone has tried to plumb a bathtub into the engine room. But the test results don’t care what it looks like. Before the modification, a Liberty ship’s acoustic signature is loud and clear at nearly twelve miles. Afterward, hydrophones struggle to detect it beyond about 0.4 miles. On paper, the ships have become almost thirty times quieter.

On April 22nd, 1943, convoy ON 184 steams out of Liverpool: forty-three merchant ships in nine columns, escorted by six corvettes and two destroyers. The six modified ships are salted through the formation: two on the starboard side, two port, two in the center. The convoy commodore is not told about the experiment. If U-boats attack, the test will be as real as it gets.

German intelligence, tracking departures and radio patterns, sends a wolfpack—Gruppe “Meise”—to intercept. Thirty-seven U-boats spread out in a patrol line across the convoy’s expected path.

On April 25th, at 2:14 a.m., mid-Atlantic, aboard U-264, Kapitänleutnant Hartwig Looks studies his chart. His hydrophone operator has been riding a faint contact for six hours.

“Contact weakening, Herr Kaleun,” the man reports. “Original bearing 290, but now intermittent. Some ships very loud. Others… almost silent.”

“Intermittent?” Looks frowns. “That’s impossible. Either there is a convoy or there isn’t.”

“Ja, Herr Kaleun, but… I’m tracking multiple signatures. Some clear out to forty kilometers, some gone at five.”

Looks orders the boat to periscope depth. Through the eyepiece, the convoy materializes out of the dark. A whole forest of masts and funnels. But his hydrophones are only tracking twenty-seven of the ships. Six vessels, scattered through the formation, are—for acoustic purposes—ghosts.

Looks does what any rational commander would do. He targets what he can hear clearly. He ignores the quiet ships.

Over the next two days, the wolfpack fights its usual brutal battle, and nine merchantmen go down—47,000 tons of cargo and thousands of men adrift in lifeboats. It is still a hard loss.

But none of the nine are Lawson’s ships.

All six modified vessels come through untouched.

When ON 184 reaches New York on May 7th, Gretton signals London: in combat, under real wolfpack attack, ships with acoustic damping were completely ignored despite being in the same columns as others that were sunk. The system works.

At Western Approaches, statisticians go to work. Before acoustic damping, average U-boat hydrophone detection range is estimated at around 11–12 nautical miles. On average, about 31 percent of ships in a convoy hit by a wolfpack are sunk. For every convoy engagement, about 1.2 U-boats are destroyed in return.

After damping is implemented more widely in the following months, the numbers shift dramatically. U-boats now have to close to well under a mile to reliably pick up convoy noise—into the danger zone of ASDIC, radar, and even visual sighting. Instead of convoys being heard from fifty miles away, many are effectively invisible until the submarines are almost on top of them. Losses per convoy engagement drop to under 5 percent. U-boat losses per convoy jump fourfold.

In May 1943, the change becomes brutally obvious. That month enters German naval history as “Black May.” Forty-one U-boats are sunk—about a quarter of Germany’s operational submarine force—while Allied merchant losses fall to 58 ships, down from ninety-six in March.

Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz writes in his war diary:

“The enemy has attained technical superiority in acoustic detection, which has deprived the U-boats of their most effective weapon: surprise. Convoys have become almost invisible to hydrophone surveillance. We can no longer predict attack positions. The old certainties have vanished.”

A captured German hydrophone operator from U-954, sunk on May 19th, tells his British interrogators:

“We could not understand it. Sometimes we heard convoy noises from great distance. Other times, ships were almost upon us before we detected them. It was as if the ocean itself had gone quiet.”

By July, acoustic damping has been fitted to 847 Allied merchant ships. Installation time has dropped to about 48 hours per vessel as dockyard crews refine the process. The cost is about $20,000 per ship—less than a tenth of the price of building a new one. From May to December 1943, Allied merchant losses drop to 329 ships, down from 729 in the previous eight months. U-boat losses climb to 237. Thousands of seamen who would have died in burning, sinking ships instead go home.

The Battle of the Atlantic is not over. It will grind on until May 1945. But the tipping point has been passed. The U-boat arm, which once hunted, is now hunted.

After the war, when the story finally comes out, Admiral Sir Max Horton writes in his memoir that of all the innovations that helped save the convoys—radar, Huff-Duff, Leigh lights, escort carriers—none were as simple or as effective as Lawson’s acoustic damping. A cook, he notes, with no formal training, solved a problem that had baffled the best minds at the Admiralty.

Commander Peter Gretton, writing in 1964, puts it bluntly:

“Tommy Lawson never fired a shot in anger. He never captained a ship. Yet he saved more seamen than many of us who did. His gift was seeing what everyone else missed: that the solution was not more machinery, but a smarter use of the sea itself.”

Between April 1943 and the war’s end, more than 2,000 Allied merchant ships and 164 escort vessels are fitted with some variant of Lawson’s system. It uses about 51,000 tons of steel—less than it would take to build seven Liberty ships—and costs about $6.2 million in wartime dollars. After the war, the principle becomes standard on U.S. Navy warships, evolving into the Prairie–Masker system: instead of static water chambers, modern ships use curtains of air bubbles to mask their noise. The physics, though, are the same ones Tommy Lawson sketched in a notebook.

As for Lawson himself, he receives the British Empire Medal in June 1945 at a modest ceremony in London. He refuses interviews and publicity. When the New York Times asks to profile him in 1947, he declines. “I just noticed something and mentioned it,” he says. “Other people did the real work.”

He goes home to Boston, opens a diner in Dorchester, marries, raises three children, and lives the rest of his life as a quiet small-business owner. His wife does not learn the full story until 1978, when a British naval historian appears at their door, researching a book on convoy innovations.

Thomas Patrick Lawson dies in 1991 at the age of 76. His obituary in the Boston Globe calls him a retired restaurateur and merchant mariner. It does not mention acoustic damping, or the 4,200 merchant sailors whose lives were statistically saved by his idea, or the fact that a high-school dropout from South Boston shifted the odds in the longest battle of the war.

At his funeral, three elderly British naval officers attend unannounced. Men who once stood watch on escort bridges in 1943, straining their ears and eyes for U-boats that never heard them coming. One of them slips a folded note into Lawson’s casket.

“Because of you,” it reads, “we came home.”

In 2011, the U.S. Naval Academy adds Lawson’s story to a leadership course with a simple lesson attached: innovation does not require credentials. It requires observation, courage, and the willingness to challenge what “everyone knows.” Lawson succeeded not because he was trained as an acoustician, but because he listened when others were too busy to hear.

In war, the most dangerous phrase isn’t “that’s impossible.”

It’s “we’ve always done it this way.”

News

How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea

January 16th, 1943. Portland Harbor, Oregon. The morning was calm and bitterly cold, the kind of cold that made steel…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Technical Sergeant James McKenna knelt beneath the left wing of a P-38 Lightning…

Japan’s Answer to the P-38 Lightning: The Truth About the Ki-61 “Tony”

On December 26th, 1943, at 0615 hours, Captain Shōgo Tōguchi stood beside his Kawasaki Ki-61, manufacturer number 263, on the…

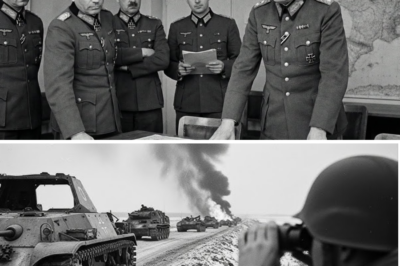

How German High Command Reacted When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

“Impossible. Unmöglich.” That was the mood inside German high command when the first reports came in. On December 19, 1944,…

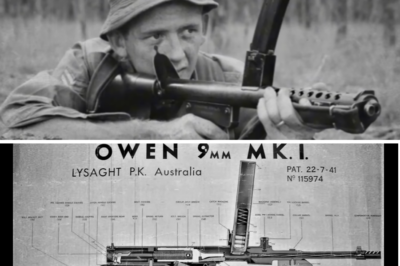

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

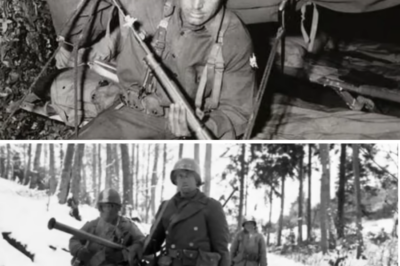

They Banned His “Rust Lock” Rifle — Until He Shot 9 Germans in 48 Hours

THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb…

End of content

No more pages to load