The Silo Sniper

How a Wisconsin dairy farmer climbed into a grain tower, rewrote the rules of counter-sniping in Normandy, and dismantled a German command structure one trigger pull at a time.

The Forty Seconds That Should Have Belonged to Sergeant Mertens

June 18, 1944 — 7:23 a.m.

Outside Carentan, a German sergeant named Jacob Mertens leaned into the third-floor window of a shattered farmhouse. Through his Kar98k scope, he studied an American machine-gun nest 200 yards away. That MG42 had killed six of his men in sixty minutes. Mertens was calm. Focused. Lethal.

He was about to die.

Not from the machine gun.

Not from Allied artillery.

Not from any threat he could see.

He died from three miles away, from a hole cut in the concrete skin of a grain silo no soldier had thought to check.

The bullet came from a farm tool repurposed into a fortress.

From a man who understood elevation, patience, and rural architecture better than the German Army understood war.

From a dairy farmer named Technical Sergeant Raymond “Ray” Kozlowski.

He’d been inside that silo eleven hours. No food. No sleep. One bucket.

Twenty-three kills behind him.

Twenty-four about to fall.

The moment Mertens leaned forward to give orders, Ray’s crosshairs settled on the iron cross pinned beneath his collar.

Half-breath.

Hold.

Squeeze.

Mertens dropped out of sight.

The Germans never even looked up.

The Farm Boy Who Wasn’t Supposed to Be a Killer

Raymond Kozlowski was born into Sheboygan County dairy land, where elevation was measured in ladder rungs, not contour lines. He was the second of five sons, which meant he drew the jobs nobody else wanted: mucking stalls, fixing fence wire, breaking up clumped silage forty feet up inside grain towers.

That last job — the one every kid tried to avoid — shaped him more than anyone understood.

Darkness.

Stillness.

Claustrophobic heat.

Hours alone inside a concrete tube where a single mis-step meant suffocating under tons of shifting grain.

He learned patience the way most boys learned sports.

He learned marksmanship the way most farmers learned chores: killing groundhogs that broke cattle legs. His uncle paid a nickel per tail. Ray shot his first one at 200 yards — at thirteen. By fifteen he was the best shot in the county. In 1937 he won the state youth championship.

His father didn’t care about trophies.

“Cows need milking,” he’d say. “Steel targets don’t.”

The Wrong War for a Farmer

When the war came in 1941, Ray was declared essential agricultural labor.

Exempt.

His cousins enlisted immediately. One came home in a box.

Ray felt the guilt like a weight.

In October 1942, he walked into a recruiting office and signed up. His father refused to speak to him for two weeks. But Ray didn’t budge. Shooting groundhogs felt like a waste now. There were men out there who needed killing.

At Camp McCoy, instructors noticed his shooting instantly. He was precise, quick, unflinching.

They asked where he learned.

He said, “Groundhogs.”

They sent him to Fort Benning sniper school.

By April 1944, he was in England with the 82nd Airborne. Still quiet. Still rural. Still carrying the guilt of leaving a farm behind.

He preferred solitary work.

He’d spent half his life alone in vertical concrete tubes. Company felt unnatural.

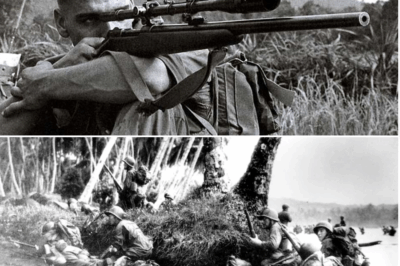

Snipers of the Cotentin — and American Blood in the Hedges

It started on D+7, June 13.

Carentan’s hedgerows became killing lanes. German snipers operated from church steeples, barn lofts, water towers — elevated positions the Americans couldn’t reach.

Ray watched PFC Eddie Kowalski (no relation) die from a throat shot at 9:15 a.m. Eddie bled out in forty seconds asking for his mother.

Ray searched for the shooter for twenty minutes.

Found nothing.

At 11:40, Corporal Develin — Ray’s roommate from England — took a perfect center-mass shot crossing a field.

Ray was fifty yards away.

He never found that shooter either.

By June 14, eleven Americans were dead from precision fire.

The Germans weren’t just shooting well.

They were shooting with a system:

Radio men first

Officers second

Leaders third

Anyone giving orders next

Sniper craft wasn’t a duel.

It was surgery.

And the Germans were specialists.

The Walk That Changed the Campaign

On June 15, Lieutenant Marcus Freeman — the man coordinating all sniper teams — took a bullet through the head at 3:20 p.m.

Ray saw him fall.

That night, Ray couldn’t sleep. He walked through captured farmland alone as the sun rose.

Barns, sheds, hedgerows, farmhouses… standard tactical terrain.

But then he saw it:

An abandoned silo, 32 feet tall, ladder rusted, concrete thick enough to stop a shell.

Ray climbed.

At the top, he saw further than he’d ever seen in Normandy.

Three miles of visibility.

Every German strongpoint.

Every sniper hide.

Every crossroads.

He dropped inside through the hatch.

Inside, through the ventilation slit, the world became a shooting gallery.

He realized the Germans had made a fatal assumption:

Farm equipment isn’t tactical terrain.

Ray smiled.

They had no idea.

“Sir, I have an idea.”

He spent June 16 testing his theory in an abandoned silo two miles behind the lines:

Angle of fire: ~40 degrees down

Holdover: different than flat-ground shooting

Mirage: negligible at elevation

Sound: echoes, but muffles behind concrete

Visibility: perfect

Concealment: total

He widened one ventilation slit with tin snips until his scope fit through.

At sundown, he approached Captain Henshaw.

“Sir, I want to use the silos.”

Henshaw stared.

“Those things are coffins,” he said. “If the Germans see you up there, you’re dead.”

“I grew up in them,” Ray answered. “I know how they breathe.”

Henshaw sighed.

“You do this, you’re alone. No support. No rescue.”

Ray nodded.

He packed his rifle.

Night Climb Into a Concrete Tomb

June 17, 9:45 p.m.

Ray moved through Allied lines like a ghost, avoided German patrols by inches, reached the silo.

At 11:20 p.m., he climbed the ladder — rung by rung, rust peeling, slick with dew. One slip and he’d fall forty feet.

The hatch was jammed. He pried it open with a shovel handle.

Dropped his pack inside.

Climbed down.

Entered darkness.

He spent the night arranging:

Sandbags

Blankets

200 rounds

Water

Rations

Bucket

Scope adjustments

Notebook

Field glasses

He lay against the concrete wall, waiting for dawn.

This was no different from a Wisconsin farm.

Only now the groundhogs carried rifles.

June 18 — The First Day of Collapse

Dawn turned the world from shadows to shapes.

At 6:58 a.m., a Feldwebel emerged from a farmhouse. Ray watched him drink from a well. Not an officer. Not a priority.

At 7:19, Lieutenant Klaus Becker — responsible for half a dozen American deaths — stepped into the open.

Ray calculated wind — 3 to 5 mph.

Range — 820 yards.

Angle — 40° down.

He exhaled to half-lung and fired.

Becker dropped backwards.

German confusion blossomed immediately.

At 8:33, Hauptmann Schultz ran into Ray’s view with a radio in hand.

A single shot to the throat.

At 9:15, Mertens appeared.

Ray’s bullet ended him.

By noon he’d killed four officers.

By sundown, seven.

German movements faltered.

Orders lagged.

Coordination crumbled.

But Ray didn’t climb down.

He stayed the night.

June 19 — A Doctrine Is Born

Ray woke at 4:30 a.m., stiff, dehydrated, exhausted.

But he killed again.

A mortar officer at 1,200 yards.

A supply sergeant coordinating ammo.

A second lieutenant leading an assault.

A captain stepping into daylight for six fatal seconds.

Twelve officers in two days.

German radio traffic — though Ray couldn’t hear it — was chaos incarnate.

Officers refused to step outside.

Sergeants took over.

Units fought disconnected.

Assaults stalled.

Ray had severed the vertebrae of the German defense.

“The Silos.”

On June 20, Sergeant Tommy Reeves — a ranch kid from Montana — noticed something.

Officers kept dying from impossible angles.

German bodies dropped with no visible shooter.

The timing, precision, and elevation didn’t add up.

He climbed a tree and looked across the countryside.

He saw it:

A silo.

A perfect angle.

A shot line consistent with every officer death that week.

When Ray returned to resupply after sixteen days, Reeves confronted him.

“The silos,” he said. “It’s the silos, isn’t it?”

Ray said nothing.

Reeves said, “I grew up on a ranch. I’m not claustrophobic.”

Ray finally nodded.

“Then find one,” he said. “Bring water.”

The Fire Spreads

By June 25, four snipers were using silos.

By June 28, nine.

By July 2, seventeen.

By mid-July:

German officers refused to expose themselves

Platoons acted leaderless

Radio discipline collapsed

Entire sectors stalled under mysterious long-range fire

A German reconnaissance officer noted “multiple sniper elevations… possible use of agricultural storage structures.”

His analyst dismissed the idea.

“Too dangerous,” he wrote. “No one would climb inside those.”

He was wrong.

By August, forty American snipers used silos across France.

By September, sixty.

By December, ninety.

And in the Ardennes, during the Battle of the Bulge, nine silo snipers killed 41 German officers in three weeks.

The Ledger of Lives

The numbers — when declassified in 1982 — told the story:

Confirmed kills per sniper quadrupled

Officer kills more than doubled

German command efficiency dropped 30–40%

American casualties from enemy snipers fell 45%

Estimated 200 American lives saved in Normandy alone

One man’s farm logic became a battlefield doctrine.

The Army incorporated it quietly in 1946 under “nontraditional elevated positions.”

They never credited the man who invented it.

The Farmer Who Put the War Behind Him

Ray returned home in 1945.

He took a bus to Sheboygan.

His father met him with a handshake.

No hug.

He worked the same 80 acres for the next 42 years.

Married Elizabeth.

Raised three children.

Avoided reporters.

Avoided glory.

Returned to the only place he’d ever felt useful — the farm.

In 1978, at an 82nd Airborne reunion, Tommy Reeves hugged him like a brother.

“Silos saved my life,” Reeves said.

Ray nodded once.

In 1991, a military historian visited his home. They talked for three hours in Ray’s kitchen. The historian finally asked:

“Do you regret anything?”

Ray looked out his window, toward the fields.

“No,” he said.

“I did what I had to. Then I came home.”

He died with no medals, no headlines, no official recognition.

But every modern U.S. sniper who learns about elevation, angle fire, unconventional hides, and patience is — unknowingly — learning from a Wisconsin farmer who sat alone in the dark with a bucket, a bolt-action rifle, and the ghosts of men he refused to let die in vain.

Technical Sergeant Raymond R. Kozlowski —

The Silo Sniper.

The man who turned grain towers into killing grounds.

News

Unfit for War – America’s Most Lethal Soldier

The impossible stand of Vito Rocco Bertoldo —48 hours, alone, against Tigers, grenadiers, and a German offensive racing for Strasbourg….

This 19-Year-Old Was Flying His First Mission — And Accidentally Started a New Combat Tactic

How a 19-year-old Mustang pilot broke every rule in the manual—and accidentally reinvented air combat for the next eighty years….

How One Gunner’s “Suicidal” Tactic Destroyed 12 Bf 109s in 4 Minutes — Changed Air Combat Forever

March 6, 1944.Twenty-three thousand feet over Germany, a B-17 Flying Fortress named Hell’s Fury carved contrails through thin, freezing air….

The Day a Loader Became a Gunner

What it felt like to move one seat over inside a Sherman—and see war for the first time through a…

The Mail-Order Rifleman

How a state-champion civilian with a sporting rifle walked alone into Point Cruz—and outshot the Japanese Army’s best snipers. A…

“What Remains Is Sacred”: Erika Kirk Shares Heartbreaking Thanksgiving Tribute to Slain Husband Charlie Kirk

In what she called the “hardest holiday of my life,” Erika Kirk marked her family’s first Thanksgiving without her late…

End of content

No more pages to load