At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Technical Sergeant James McKenna knelt beneath the left wing of a P-38 Lightning at Dobodura Airfield in New Guinea, watching his pilot walk toward an airplane he was almost certain the man wouldn’t come back in. The pilot was 23-year-old Lieutenant Robert Hayes. Six combat sorties. Zero kills. And today, he was flying straight toward eighteen Mitsubishi A6M Zeros sent up to intercept the morning patrol.

McKenna had been living with the Lightning for eight months. He knew every panel and cable on the twin-boom fighter: twin engines, heavy armament, vicious speed, and brutal performance at high altitude. On paper, it was a monster. In a turning fight with a Zero, it was a liability. The Japanese fighter was lighter, stripped of armor and self-sealing tanks, and could whip around in a flat turn in about half the time a P-38 needed. In a dogfight, that meant one thing: the Zero ended up behind you and stayed there.

American doctrine tried to work around that hard truth. Pilots were drilled: never turn with a Zero, never try to out-twist them. Use speed, use altitude. Dive in, fire, climb away. Hit and run. Don’t get pulled into a horizontal turning fight. Hayes had done exactly that for five missions and had nothing to show for it. The Japanese weren’t stupid. They had learned the American playbook. They baited Lightnings into turns, reversed quicker, slid inside their turning radius, and shot them down. In the past six weeks alone, Fifth Air Force had lost thirty-seven P-38s. Most died in turning engagements they couldn’t escape.

McKenna had watched too many pilots swagger out to their planes and come back in boxes—when they came back at all. Officially, the fault was always the same: pilot error, bad tactics, failure to follow doctrine. The instructors blamed the men in the cockpit. McKenna didn’t. In his mind, the problem wasn’t just the pilot. It was hiding inside the airplane, buried in steel and pulleys and cable runs.

On the P-38, the aileron control cables ran back through each boom, wrapped around pulleys in the tail, then came forward again to the wing control surfaces. Somewhere along that route there was always a touch of slack. Not much—about three-eighths of an inch at full deflection—but enough that there was a tiny pause between moving the stick and feeling the ailerons bite the air. At high speed in gentle maneuvers, you hardly noticed. At low speeds in a hard, desperate turn with a Zero closing in, that fraction of a second became the difference between rolling inside the enemy’s turn or getting hit.

Two months earlier, McKenna had raised this with the engineering officer. The response had been a wall of regulations. Cable tension was “within spec.” The factory tolerances allowed that much play. Tightening it beyond that would violate design assumptions, maybe even void warranties. And no field mechanic had the authority to alter flight control systems. That required engineering sign-off from Lockheed—7,000 miles away in California. The war in New Guinea would not wait for California.

So McKenna stopped waiting for permission.

He took a six-inch length of high-tensile piano wire from a wrecked P-38, bent it into a rough Z-shape, and used it as an improvised inline tensioner on the left aileron cable of Hayes’s Lightning. The modification took eight minutes. That little piece of wire added about 0.4 pounds of preload to the cable—just enough to pull the slack out of the system completely. No paperwork, no authorization, no signatures. The morning inspection team checked the usual—fuel, oil, ammunition—no one measured the precise feel of a cable buried in a boom. McKenna kept his mouth shut and watched.

He watched Hayes taxi out, watched the Lightning roar down the strip and lift into the pale New Guinea morning, watched it merge with sixteen other P-38s and fade toward Japanese airspace. What happened over the Huon Gulf in the next seventeen minutes would quietly rewrite how the P-38 fought in the Pacific.

McKenna hadn’t come to this conclusion overnight. The first pilot he lost to a Zero was Lieutenant David Chen. July 9th, 1943. Chen had been in theater three weeks. They talked every morning while McKenna worked on his aircraft—two California kids who’d turned wrenches on cars before the war, Chen from Sacramento, McKenna from Long Beach. That day Chen launched at 06:15 on a fighter sweep over Lae and came back two hours later with three clean bullet holes in his left boom and a shaken story about a Zero that had nearly killed him.

Chen had done exactly what the manual said: rolled out of the turn, pushed the nose down, tried to dive away. But he swore the airplane felt slow to respond, like it was half asleep. The roll lagged his inputs just long enough for the Zero to hold perfect lead. Only his wingman’s timely burst had saved his life. McKenna inspected the damage. The bullet holes were in a tight pattern—beautiful deflection shooting. That shouldn’t have been possible if Chen’s Lightning had snapped into the roll instantly. Something had hesitated.

Chen’s aircraft was sent to the depot for repair. Chen moved to another Lightning. Three weeks later, word came back: he’d been killed over Rabaul. Same story. Turning fight. Couldn’t roll out fast enough.

Then came Captain William Morrison. Eleven kills. Experienced. Smart. The kind of pilot who knew his airplane’s limits and flew within them. On August 3rd, at 12,000 feet over Oro Bay, his flight intercepted eight Zeros. He got one on the first pass and swung around for a second run. Two Japanese fighters reversed on him. Later, McKenna heard the radio recording. Morrison rolled to go inverted and split-S away. His last transmission was composed but chilling: “Controls feel mushy…” Seconds later, Japanese guns tore him apart. His wingman watched the P-38 wallow through the escape roll like it was fighting glue before it went in at 4,000 feet.

Maintenance crews took the wreck apart piece by piece. Engines, rigging, cable tensions—everything checked “within spec.” The official verdict was pilot error. Morrison’s crew chief, Rodriguez from Texas, didn’t believe it. McKenna didn’t either. By mid-August, McKenna had watched seventeen pilots die in aircraft whose maintenance logs carried his signature. Survivors kept describing the same slight lag between moving the stick and feeling the airplane really bite into a hard turn. The manuals said that was normal—big fighter, big control surfaces, some delay expected. His hands said it wasn’t. Every time he tensioned a cable, he felt that looseness. When he plucked them, tight cables rang high and sharp; the ones on the line gave a softer, duller twang. Officially acceptable. To him, wrong.

He and Rodriguez talked about it one evening after Morrison’s death. Rodriguez asked what could be done. McKenna told him there was a solution—but not a legal one. It meant breaking rules that could get them both court-martialed.

Three days later, Hayes came looking for him.

The squadron was still reeling from the loss of Lieutenant Thomas Parker on August 14th. Parker, 21, from Boston, had trained with Hayes. During a chaotic dogfight over Finschhafen, he got separated from the formation. Two Zeros locked onto him. Hayes heard everything over the radio: Parker calling for help, Parker saying his aircraft wouldn’t turn fast enough, the rising fear in his voice, then gunfire, then a scream, then nothing.

Parker’s bunk stayed empty. His things were boxed up and sent home. His P-38 was logged as a combat loss. No mechanical issues noted. Again, the paperwork blamed “pilot error.” McKenna had serviced that aircraft the same morning. Everything had been fine. Within spec. And Parker was dead.

That evening, in the maintenance area, Hayes found McKenna. He didn’t talk like an officer giving an order. He talked like a man on borrowed time.

“Is there anything you can do to make my bird roll faster?” he asked. “Anything at all. I don’t care if it’s in the book or not. I just want a chance.”

McKenna saw the fear and the quiet certainty in his eyes—the look of someone who knew his number was coming up if nothing changed.

“Come back in the morning,” McKenna said. “I’ll see what I can do.”

That night, after most of the crew had turned in and Dobodura had settled into its usual mix of generator hum and insect buzz, McKenna worked alone. The hangar smelled of engine oil and hot metal cooled by tropical air. He pulled the inspection panel off the left boom of Hayes’s P-38. The skin was still warm from the day’s sun. Inside, the aileron cable ran over its pulleys toward the tail.

He grabbed it with both hands and pulled. There it was—maybe three-eighths of an inch of play before the cable caught tension. His fingers ached from a day of work, but he could feel that slack clear as daylight. It was wrong.

From his tool bag he took the six-inch bit of piano wire he’d stripped out of a ground-looped P-38’s trim system weeks before. Sitting on the hangar floor with a pair of pliers, he bent it into a Z. The wire fought back. Twice his hand slipped; the pliers bit into his thumb and blood made the metal slick. He wiped it on his coveralls and kept going. Eight minutes later, the wire was shaped the way he wanted: a simple inline tensioner.

Installing it in that cramped space was harder. He wedged his shoulder against the boom structure, held the flashlight under one arm, and worked one-handed to disconnect the cable at a pulley junction. The tiny clevis pin slipped free and vanished inside the boom. For five long minutes he groped blindly through the dark metal maze until his fingers finally brushed it. His heart thudded. If the engineering officer walked in now, McKenna knew exactly how the story would end: charges, prison, disgrace.

But he also knew how Hayes’s story would end if he did nothing.

He slotted the Z-shaped wire between the cable end and the pulley fitting, forced the clevis pin back through the assembly, and tugged on the cable. No slack. The control surface moved the instant he pulled.

Perfect.

He closed the panel, wiped his hands as clean as he could, and walked out of the hangar at 01:15. The night was thick and still. Somewhere out over the jungle, aircraft engines droned—probably Japanese raiders hunting in the dark. If that little piece of wire failed, Hayes would crash and the blame would land on him. If it held, Hayes might live. McKenna went to his bunk and stared at the ceiling until dawn without sleeping.

At 06:30, he was back on the flight line. He watched ground crews fuel and arm Hayes’s P-38. He watched Hayes attend his briefing and climb into the cockpit. At 07:42, the Lightning roared down the runway and clawed into the morning sky. McKenna watched it climb, join fifteen other P-38s, and disappear toward Japanese airspace. Then there was nothing to do but wait.

At 08:14, over the Huon Gulf, Hayes’s four-ship element spotted nine Zeros at 13,000 feet. The sun was at their backs. Perfect conditions for a dive attack. The element leader called the bounce. They rolled in. Hayes, flying number three, picked a trailing Zero. He dropped his nose, accelerated to 380 mph, and watched the Japanese fighter swell in his gunsight. He could see the red roundel on the fuselage and the pilot’s helmet in the canopy.

He squeezed the trigger. Four .50-caliber machine guns and a 20 mm cannon spat fire. Tracers reached out. Most missed. A few sparks jumped from the Zero’s wing. Not enough. The Japanese pilot snapped right and dove.

Hayes rolled to follow.

That was the moment he felt it.

The Lightning snapped into the roll. No mushiness. No hesitation. The airplane responded the instant he moved the stick. For the first time since arriving in New Guinea, Hayes felt like the P-38 was truly alive under his hands. He ripped through ninety degrees of bank in what felt like half the normal time, dropped his nose, and found the Zero right back in his sight picture.

He fired a three-second burst. The stream of bullets walked up the fuselage from tail to cockpit. The engine exploded. The Zero rolled inverted and fell toward the jungle trailing black smoke. Hayes had his first kill.

There was no time to enjoy it. His wingman shouted a warning—Zeros diving from above. Three Japanese fighters were dropping on him, eager to avenge their comrade. Instinct and training screamed at him to run, climb, use speed, don’t turn with Zeros. But doctrine had gotten Chen, Morrison, and Parker killed.

Hayes shoved the throttles forward and did the unthinkable. He rolled hard left and pulled.

The P-38 whipped around like a different airplane. The lead Zero, expecting the usual sluggish response, was caught off-guard. Hayes’s reversal beat his timing. For a fraction of a second, the Zero hung exposed in Hayes’s gunsight. He pulled lead and fired. Rounds tore into the wing root. The left wing snapped off, and the fighter tumbled out of the sky in pieces.

Two kills in thirty seconds.

The remaining two Zeros tried to scissor with him, reversing their turns to force an overshoot. But every time they changed direction, Hayes’s P-38 snapped with them instantly. No lag. No sense of pushing against dead weight. It was as if someone had cut invisible sandbags loose from the control system. One Zero reversed too hard, bled too much speed. Hayes slid inside his turn at maybe 200 feet of separation and fired at point-blank range. The Japanese fighter came apart. Debris bounced off Hayes’s right boom.

Three kills. The fourth Zero decided he’d seen enough and ran. Low on fuel and ammunition, Hayes climbed back to altitude, rejoined what remained of his flight, and headed home. The entire engagement had lasted seven minutes.

At 09:03, Hayes landed at Dobodura. McKenna was waiting on the flight line. Hayes shut down, climbed out, his hands shaking, his flight suit soaked in sweat. He walked straight up to McKenna, grabbed his shoulder, and said only two words.

“It worked.”

What neither of them knew yet was that six other pilots had watched the whole fight from 15,000 feet. One of them was Captain Frank Mitchell of the 475th Fighter Group. From his vantage point, Hayes’s Lightning looked… wrong. It was rolling faster than any P-38 he’d ever seen, snapping through maneuvers like it weighed half as much. Hayes was a good pilot, but not that good. Something about the aircraft itself had changed.

After landing, Mitchell found Hayes in the debriefing room, still keyed up, filling out a combat report listing three confirmed kills. Mitchell asked him what was different. Hayes could only say that his airplane had responded better—faster—than it ever had before. When Mitchell asked if maintenance had done anything special, Hayes told him to talk to Technical Sergeant McKenna.

Two hours later, Mitchell walked into the maintenance area and found McKenna working on another Lightning, hands black with grease, coveralls stained. He asked him directly what he’d done to Hayes’s airplane. McKenna hesitated, then told the truth: the piano wire tensioner, the unauthorized modification, the risk to them both if anyone found out. Mitchell listened in silence. When McKenna finished, Mitchell asked a single question.

“Can you do it to mine?”

McKenna warned him—unapproved, untested, absolutely against regulations. Mitchell, who had lost four pilots from his flight in the last month, didn’t care. He wanted his men to have a chance. That night, McKenna modified Mitchell’s P-38 the same way. The next morning, Mitchell flew it and came back almost laughing at the difference, telling his wingman the Lightning finally rolled like a fighter instead of a truck. The wingman wanted the modification too.

By August 20th, McKenna had quietly modified nine aircraft. Word spread in low voices in ready rooms and maintenance bays. Pilots began asking their crew chiefs if they’d heard about the cable mod. Some chiefs refused to risk it. Others decided rules could wait until after the war. McKenna showed them how: cut six inches of piano wire, bend it into a Z, slip it into the cable run. Eight minutes of work. Total change in feel.

Hayes shot down two more Zeros on August 22nd. Mitchell got three on August 25th. Other pilots started coming home with kills instead of complaints. In July, P-38s in the Southwest Pacific had lost about two Lightnings for every Zero they destroyed. In August, the ratio improved to about 1.3 to 1. By September, it was nearly even. Officially, nobody could point to a specific change. On paper, the aircraft were the same.

The Japanese noticed first. Reports from the 11th Air Fleet in late August complained that P-38s were maneuvering more aggressively, rolling into turns and reversing direction faster than before. Tactics that had worked reliably for months were suddenly failing. On September 3rd, ace Saburō Sakai, with over sixty kills to his name, engaged a P-38 over Wewak. He used the same trick he always used: pull the American into a turn, wait for the P-38 to start rolling, then snap his Zero back the other way and cut inside the slower roll.

Except this time, the Lightning reversed with him.

Sakai nearly collided head-on with the P-38. The American even managed to get his guns onto him. Sakai had to break away and dive, shaken. Japanese pilots began reporting that the Americans weren’t flying differently—their planes were reacting differently. Just a little. Just enough to throw off the fine-tuned timing of Zero tactics. Japanese intelligence examined wrecked P-38s and found nothing obvious. Same guns, same engines, same structure. The tiny Z-shaped wire buried in the boom looked like any other bit of hardware—if anyone even noticed it at all.

By the end of September, the 11th Air Fleet had lost thirty-eight fighters in combat with P-38s. American losses in those engagements were twenty-two Lightnings. For the first time in the Pacific, P-38s were killing Zeros at better than a one-to-one rate. Japanese command quietly ordered their pilots to avoid engaging P-38s unless they had a clear numerical advantage. The Zero, for so long the hunter in turning fights, was now being told to treat the Lightning with caution.

Back at Dobodura, the modification remained unofficial and technically illegal. In October 1943, a maintenance inspector finally noticed inconsistent cable tension readings and traced them to the piano wire tensioners. He wrote a report and sent it up the chain of command, where it sat on desks for three weeks while officers argued. The mod clearly violated regulations, but also clearly worked. Squadrons using it had better kill ratios. Their pilots were surviving.

In November, Lockheed sent an engineering team to New Guinea to evaluate the field modification. They measured cable loads, calculated stresses, ran flight tests. Their conclusion was blunt: the mod was safe and effective. It should have been part of the original design. Lockheed incorporated a proper tensioning system into the P-38J model that began rolling off production lines in December 1943. The official documentation credited the change to engineering analysis. McKenna’s name never appeared anywhere.

Hayes survived the war. He flew sixty-three combat missions, shot down eleven Japanese aircraft, went home to Iowa in 1945, married his high-school sweetheart, had four children, and spent thirty-seven years flying crop dusters over fields instead of jungles. Every year on August 17th, he called James McKenna to thank him for saving his life. Mitchell survived as well, became a squadron commander, led his men through the Philippines campaign, finished the war with sixteen kills, stayed in the Air Force, and retired as a colonel in 1963. To every young maintenance officer he mentored, he told the story of the sergeant who saw a problem the engineers missed and fixed it.

McKenna stayed in the Army Air Forces until 1946, then returned to California. In 1948, he opened a garage in Long Beach and spent the next four decades working on engines. He rarely talked about the war. When people asked, he would just say, “I was a mechanic. Fixed airplanes.” In 1991, a military historian researching P-38 modifications noticed repeated references to “piano wire tensioners” in maintenance logs from New Guinea and traced them back to McKenna. At seventy-three, still working part-time at his shop, McKenna confirmed the story and insisted it wasn’t anything special, just something that needed doing. The historian estimated that the modification might have saved between eighty and a hundred pilots based on survival rates in units that used it. McKenna said he’d never tried to count. He just remembered the ones who came back—Hayes, Mitchell, Watkins, and others. That was enough.

James McKenna died in 2006 at age eighty-eight. His obituary mentioned his service in World War II as an aircraft mechanic. It didn’t mention the piano wire, or the way he’d changed how American fighters handled in combat, or the regulations he’d quietly broken to save lives. The garage in Long Beach is still there under a different owner. In the back office, on a faded corkboard, there’s an old photograph of a young man in oil-stained coveralls standing beside a P-38 Lightning. On the back, in faint handwriting, are the words: “August 1943 – New Guinea.”

That’s how innovation often happens in war. Not through committees or official programs, but through sergeants and mechanics who see a problem, find a solution, and refuse to wait for permission to keep someone alive.

News

How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea

January 16th, 1943. Portland Harbor, Oregon. The morning was calm and bitterly cold, the kind of cold that made steel…

How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Stopped U-Boats From Detecting Convoys

March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, roughly 400 miles south of Iceland. Convoy HX 229 forces its way through 15-foot winter…

Japan’s Answer to the P-38 Lightning: The Truth About the Ki-61 “Tony”

On December 26th, 1943, at 0615 hours, Captain Shōgo Tōguchi stood beside his Kawasaki Ki-61, manufacturer number 263, on the…

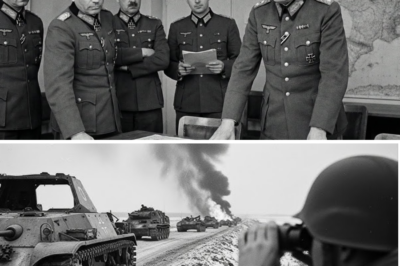

How German High Command Reacted When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

“Impossible. Unmöglich.” That was the mood inside German high command when the first reports came in. On December 19, 1944,…

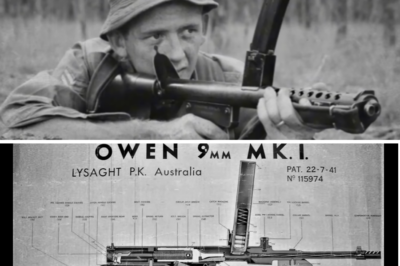

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

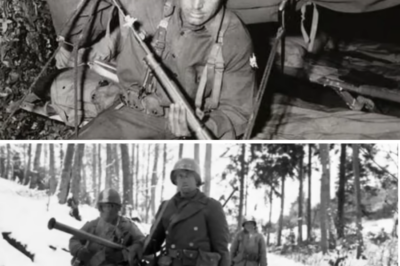

They Banned His “Rust Lock” Rifle — Until He Shot 9 Germans in 48 Hours

THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb…

End of content

No more pages to load