January 16th, 1943. Portland Harbor, Oregon.

The morning was calm and bitterly cold, the kind of cold that made steel ring sharper and breath hang in the air. The harbor lay still under a pale gray sky, the water a near-perfect mirror broken only by the slow wake of tugboats nosing along the piers.

Dockworkers moved through the fog in heavy coats, coffee in hand, boots clanging on the frozen planks as they prepared another Liberty ship for inspection. The SS Schenectady had only recently been launched from the Kaiser yards, her hull still smelling of paint and burnt metal. She was everything America was proud of: an all-welded cargo ship, built in record time, proof that U.S. industry could out-build Hitler’s U-boats.

At 11:15 a.m., that pride screamed.

First there was a single sharp metallic crack, like a rifle shot echoing across the harbor. Heads turned. Then another. Then a rapid-fire series of pops and bangs, like steel tearing itself apart.

Dockworkers stared in disbelief as the Schenectady’s hull began to move.

Men later said it looked like the ship was breathing. The deck plates rippled, flexing up and down as if some invisible force were pushing from below. Then, with a roar like a giant sheet of ice breaking, the deck split open. A jagged fracture raced along the hull, bow to stern, in less than a second.

The ship tore itself in half while tied to the pier.

When the noise died, the Schenectady was no longer a ship. She was two broken halves of twisted steel, her keel snapped, her deck hanging over the black water like torn paper. There had been no storm, no explosion, no torpedo. She had simply cracked in two on a still day, in a safe harbor.

It made no sense.

Investigators arrived within hours. Naval engineers and shipyard men swarmed the wreck, boots clanging on cold metal as they traced the fracture lines. What they saw unsettled them. The break surfaces were smooth and bright, almost like shattered glass, not torn like ductile steel. It looked less like metal that had failed under overload and more like something that had simply… snapped.

Bad welds, some said. Cheap steel, others argued. Design flaws, sabotage, rushed construction—every theory was thrown at the wreck. But none of them explained why the ship had failed so violently, in calm water, and why this wasn’t the first time.

Because the Schenectady was just the latest in a growing list.

In the months before that morning, Liberty ships had begun breaking in half all over the world. The SS John P. Gaines had snapped in two off Alaska in gentle seas, tossing her crew into freezing water. The tanker Manhattan fractured so suddenly that sailors thought they’d been hit by a torpedo. Between 1943 and 1944, more than 2,500 ships reported serious structural cracking—hulls, decks, and bulkheads splitting; steel plates shearing as if made of glass. Nineteen broke completely in two. Three simply vanished at sea, leaving only scattered debris and oil slicks.

These weren’t enemy kills. They were ships destroying themselves.

Every one of them was built the same way: welded instead of riveted, produced at record speed in yards that had become symbols of American industrial miracle.

To understand the problem, you had to understand what a Liberty ship was.

After Pearl Harbor, the United States faced a brutal math problem. It needed cargo ships—hundreds, then thousands—to haul weapons, fuel, and food across two oceans. Traditional shipbuilding could take eight months for a single vessel. By then, the war might already be lost at sea.

Enter Henry J. Kaiser.

Kaiser had never built a ship in his life. He was a dam builder, famous for Hoover Dam, not hulls. But when the Maritime Commission approached him, he made a wild promise: he would build cargo ships like cars—using prefabricated sections, welding instead of riveting, and assembly-line techniques that could turn out a ship in weeks instead of months.

By late 1942, Kaiser’s idea looked like a miracle. His yards were launching Liberty ships in around 40 days. One, the SS Robert E. Peary, went from keel to launch in just 4 days, 15 hours, and 26 minutes. Newsreels showed women in overalls—“Rosie the Riveter,” though many were welders now—throwing sparks in three shifts, 24 hours a day. Banners proclaimed: “Speed Wins Wars.”

For a while, it seemed they were right.

But speed had hidden costs.

In the North Atlantic, where winter seas ran black and temperatures hovered near freezing, Liberty ships began to fail in strange ways. The welded hulls that had allowed such rapid production behaved differently than the old riveted ones. Tiny cracks that should have stopped at a riveted seam instead ran unchecked across entire hulls—devouring steel in seconds.

The very process that made them fast to build was making them dangerously brittle.

Sailors started to fear the ships meant to save them. Some refused to sleep below decks, worried they’d be trapped if the hull suddenly gave way. Others swore they heard eerie metallic “pings” echoing through the steel, like glass bending just before it shatters, hours before disaster. Engineers dismissed it all as superstition.

But the cracks were real.

By late 1943, the Liberty program—once the shining symbol of American industrial might—was becoming a national embarrassment. Every sudden fracture wasn’t just a ship lost; it was a broken artery in the Allied supply chain: thousands of tons of cargo gone, hundreds of lives lost, confidence shaken.

The press called it “the mystery of the breaking ships.”

In Washington, committees were formed. Naval architects blamed welders. Welders blamed steel mills. Steel mills blamed designs. Designs blamed “inexperienced labor.” While they argued, more ships broke apart in the night.

And in one of Henry Kaiser’s shipyards in California, a woman nobody knew was about to see what all the experts had missed.

Kaiser’s shipyards in Richmond, California, and Portland, Oregon, were unlike anything the shipbuilding world had seen. Instead of slow, careful work around a single hull, huge prefabrication sheds produced entire sections of ships that were then welded together. Welding had replaced most riveting: faster, lighter, and requiring smaller teams.

But welding wasn’t just “hot glue.” It introduced new kinds of stresses no one fully understood.

Riveted hulls were, in a sense, naturally segmented. Each riveted seam acted like a crack stopper. A fracture could start, but often it would be arrested at the next row of rivets. Welded hulls, by contrast, were continuous. From bow to stern, they were almost one piece of steel. Strong under compression, yes—but if a crack started and nothing stopped it, it could race along that continuous path unhindered.

In Richmond, under relatively mild coastal weather, the problem stayed invisible. The ships slid down the ways and sailed into service without any hint of the doom hidden in their hulls.

Far out in colder waters, steel behaved differently.

Below about 40°F, the carbon–manganese steel used in Liberty ships lost ductility—the ability to bend and yield. Its internal crystal structure shifted. It didn’t stop being steel, but it stopped acting like the kind of steel engineers were used to. Instead of denting and stretching under stress, it behaved more like ceramic: one tiny flaw could become a catastrophic fracture.

And the way the yards were welding these ships all but guaranteed those flaws.

The production system rewarded speed. Welders—many of them women new to heavy industry—were trained to run long seams straight through, end to end, in single passes whenever possible. It met quotas. It looked efficient.

But each weld dumped intense heat into the plate. As the molten metal cooled, it contracted. If a long seam was welded from one end to the other, that contraction pulled the surrounding plate with enormous force. The hotter weld zone tried to shrink while the cooler steel around it resisted. The leftover imbalance was locked in as “residual stress”—invisible but very real tension stored inside the hull.

Every ship left the yard carrying millions of pounds of internal stress, like a spring wound up and held in place.

On a warm day in San Francisco Bay, you never knew it was there. In freezing Atlantic swells, where the hull flexed with each wave and the steel had become brittle, all it took was a nick at a hatch corner, a tiny weld defect, or a sharp edge to start a crack. And with the whole structure welded solid, that crack could run unchecked from one end to the other.

The experts blamed everything but the process. Meanwhile, down on the night shift of Richmond Yard No. 3, one welder was quietly watching steel in a way no engineer ever had.

Her name was Bessie Hamill.

To the payroll office, she was just another worker in coveralls, badge number on a timecard. To the night shift, she was that welder who seemed to listen to metal. She had been there eight months, long enough to know the feel of a good weld through the weight of her torch, the sound a plate made when it cooled.

Most people heard the shipyard as one big roar. Bessie heard details.

A clean, balanced weld hummed with a low, steady ring when you tapped near it. A stressed joint rang sharper, higher, a tight, strained note—like a violin string pulled too far. She saw the plates they were welding bow and twist as they cooled. Twenty-foot slabs of steel an inch thick that no longer lay flat but bowed in strange patterns, as if fighting the shape they were being forced into.

Most welders learned to muscle those plates into position with clamps and hammers and keep going. Bessie stopped to watch.

She began to notice a pattern. The standard sequence—start at the edges, run long continuous seams, fill in toward the center—always left the steel warped and tight. She started sketching what she saw in a cheap notebook she kept in her lunch pail: simple drawings of plates, weld lines, arrows showing where the steel seemed to pull, notes on which seams made the metal move the most.

On her own time, she ran small experiments with scrap plate. She welded one piece from edge to edge in a straight pass; it warped dramatically. She welded another starting near the middle, alternating sides and breaking long seams into shorter segments; when it cooled, it stayed flatter.

She took her warped test plates to her foreman.

“You’re a welder, not an engineer,” he told her. “Follow the blueprints. Hit your quota.”

But the evidence wouldn’t leave her alone. And every time she saw a headline about another Liberty ship cracking, she imagined the tens of thousands of welds that had gone into it, each one locking a bit more tension into the hull.

So she did something shipyard workers were not supposed to do. She challenged the process officially.

In November 1943, she signed a form requesting a meeting and wrote one line under “subject”:

“Stress from improper welding sequence causing hull failure.”

Her supervisors showed up expecting a complaint about break times or equipment. Instead, they found test plates, chalk marks, and a welder calmly explaining heat flow and residual stress in plain language.

She showed them plates welded the standard way: edges first, long continuous seams. Bent. Twisted. Then plates welded her way: center first, alternating sides, shorter staggered seams. Much flatter. Less warping. She didn’t quote equations. She simply laid the evidence on the table.

Most of them brushed her off. Bad steel, one said. Too much theory, another muttered. But one supervisor—an older man named Charles Horton—lingered.

He’d been around long enough to know that big failures often started with small ignored details.

That night, Horton came to watch her weld. He saw how she paced her passes, how she alternated sides, how she let the metal cool between seams, how the plate settled calmly instead of twisting against the clamps.

When that test piece cooled and lay nearly flat, he told her, “Do it again.”

It was the start of an experiment that would end up rewriting shipbuilding practice worldwide.

In a quiet corner of Yard 3, out of sight of the production lines, Horton arranged a controlled test. Two identical steel panels—twelve feet long, two inches thick—were set up. One was welded the standard way: long seams from one end to the other, edges first, fast to satisfy quotas. The other was welded using Bessie’s sequence: start near the center, alternate sides, break long runs into smaller segments, let each zone cool enough before hitting the next.

When the plates cooled, the difference was obvious. The standard plate had visibly twisted along its length, edges and center pulled out of plane. The plate welded Bessie’s way was nearly flat. Strain gauges confirmed what eyes could see: the standard procedure left high pockets of locked-in stress; hers distributed that stress more evenly and at much lower magnitudes.

They repeated the tests with thicker plates, more complex joints, sections around simulated hatch corners. Time after time, the pattern held.

Word of this “ridiculous welder experiment” reached Henry Kaiser’s office within days.

For months, he’d been under political fire. The Liberty fractures had become a scandal. The Maritime Commission wanted explanations. Congress wanted someone to blame. Now, in a test bay in Richmond, a welder with no degree had provided both a diagnosis and a fix.

Kaiser ordered a formal demonstration. Metallurgists from the University of California came. Engineers from the Maritime Commission. They tested Bessie’s plates, cut samples, analyzed microcracks, and loaded the panels until failure. The standard-weld specimens cracked along familiar lines—the same patterns seen in broken Liberty hulls. The “balanced sequence” plates, welded her way, either didn’t crack at all under equivalent loads or stopped cracks within inches.

Kaiser looked at the data, then at his production schedules.

Stopping to retrain welders now would undermine everything he’d promised: unbeatable speed, miracle output. Ninety thousand workers, three shifts, dozens of suppliers—his entire empire had been built around the idea that faster was always better.

But the ships were breaking. And the numbers said why.

He made the hardest decision a man addicted to speed could make.

“Stop the line,” he ordered. “We start again. Retrain them all.”

Overnight, the yards went from pure factories to part classroom, part laboratory. Welders who’d been judged by how many feet of seam they laid per hour were now taught to think about sequence and stress. Posters appeared on shop walls:

“CENTER OUT, NEVER IN.”

Each welder was given a small card showing the correct order for their section: start here, then here, alternate sides, no continuous seams beyond a certain length. Stress-relief ovens were installed for critical parts—huge furnaces where welded assemblies were heated and allowed to cool slowly to bleed off locked-in tension.

Production fell. Days stretched. Schedules slipped. Critics piled on. Kaiser was accused of sabotaging his own miracle. The Navy worried about shortfalls in new tonnage.

But as the weeks went by, something subtle happened.

The rework evaporated. Weld rejection rates dropped. Parts that once had to be hammered and forced into place now fit cleanly. Finished sections stayed within tolerance. The familiar eerie pings and pops of strained steel at night dwindled and disappeared.

To outsiders, it was a slowdown.

To those in the yard, it felt like the ships themselves had stopped fighting.

At the same time, metallurgists were attacking the other half of the problem: the steel. Liberty ships had been built using a common carbon–manganese steel that worked fine in warm conditions but turned brittle in the cold. Tests showed that at around 40°F, the steel’s behavior changed dramatically. It stopped bending and started breaking.

The answer was a refined alloy: so-called “killed” steel, where aluminum was added during smelting to remove dissolved gases; slightly adjusted manganese content; and a trace amount of nickel to toughen the steel at low temperatures. The shift lowered the temperature at which the steel turned brittle from around 40°F to near 5°F—enough to survive in icy North Atlantic waters.

Alongside the new welding sequence, designers also attacked the geometry that had betrayed the Liberty hulls. Those square hatches and sharp corners that were so easy to cut and build turned out to be amplifiers of stress. Under heavy seas, they acted like focus lenses for tension—multiplying loads three or four times and giving cracks a perfect starting point.

Victory-class ships, the Liberty successors, were redrawn with rounded hatch corners, smoother transitions, thicker plates where needed, and deliberate “crack arresters”: short stretches of riveted joints intentionally used in a mostly welded hull. If a crack did begin, those riveted segments would disrupt and dissipate its energy before it could run away.

Strength, they realized, wasn’t perfection. It was forgiveness.

In March 1944, the first full hull section for a Victory ship welded under Bessie’s balanced sequence was completed. Stress tests showed no significant residual tension, no microcracks. When the first complete Victory-class hull, the SS Benjamin Warner, slid into the water that June and passed sea trials without a single structural issue, the shipyard workers held their breath—then exploded into cheers.

It wasn’t just another ship.

It was proof that they’d finally learned how to build steel that wanted to hold together.

By war’s end, 531 Victory ships had entered service. Not one of them broke in half. Not one suffered a catastrophic brittle fracture like those that had plagued the Liberty class. Many would go on sailing for decades after the war as freighters, troopships, and relief vessels.

In 1947, the American Welding Society published a new Structural Welding Code. Buried in its technical diagrams and dense paragraphs was a formal description of the “balanced welding sequence.” It didn’t carry Bessie’s name. It referred instead to “best practice developed in wartime shipyards.”

The practice spread far beyond ships.

When engineers designed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, thousands of miles of welded steel over frozen tundra, they used principles born in those Richmond experiments. When the Golden Gate Bridge was strengthened for earthquakes decades later, the welding models behind its retrofit looked a lot like what Bessie had felt in her hands. Nuclear pressure vessels, offshore platforms, tall buildings—all quietly inherited that same idea: control the sequence, control the stress.

The world moved on. The cranes in Richmond went still. The yards closed. Liberty ships were scrapped; Victory ships sailed on.

Bessie clocked out for the last time in 1946. No band played. No reporter showed up. Her final paycheck was handed to her in an envelope, and she walked home through streets filled with people who would never know what she’d done.

Historians would write shelves of books about Henry Kaiser and the “miracle of mass production.” They would talk about Liberty ships, Victory ships, and the brilliant engineers who designed them. In most of those volumes, you wouldn’t find her name.

She died in 1987. Her obituary mentioned that she had “worked in wartime shipyards” and that she liked gardening.

But if you walk today aboard one of the few preserved Victory ships still afloat—with their smooth, clean weld seams running along their hulls—the steel still whispers her lesson.

Strength is not just about making things hard. It’s about letting them move the way they need to move.

And sometimes the person who understands that best isn’t the one with the degree; it’s the one who’s stood closest to the work, listening to the metal breathe.

News

How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Stopped U-Boats From Detecting Convoys

March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, roughly 400 miles south of Iceland. Convoy HX 229 forces its way through 15-foot winter…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Technical Sergeant James McKenna knelt beneath the left wing of a P-38 Lightning…

Japan’s Answer to the P-38 Lightning: The Truth About the Ki-61 “Tony”

On December 26th, 1943, at 0615 hours, Captain Shōgo Tōguchi stood beside his Kawasaki Ki-61, manufacturer number 263, on the…

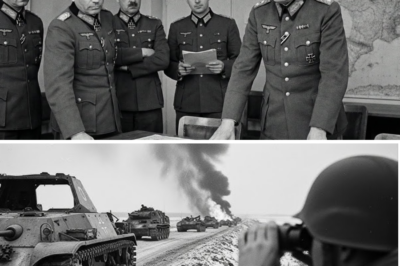

How German High Command Reacted When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

“Impossible. Unmöglich.” That was the mood inside German high command when the first reports came in. On December 19, 1944,…

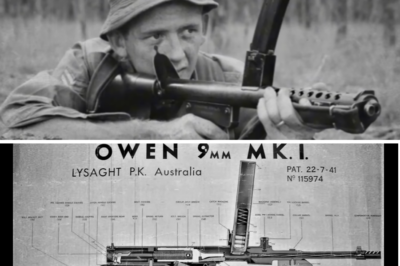

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

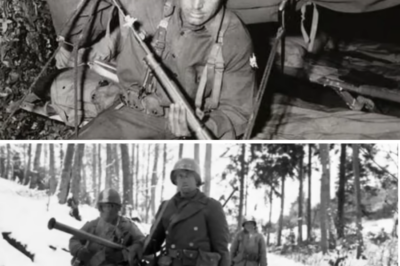

They Banned His “Rust Lock” Rifle — Until He Shot 9 Germans in 48 Hours

THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb…

End of content

No more pages to load