On December 26th, 1943, at 0615 hours, Captain Shōgo Tōguchi stood beside his Kawasaki Ki-61, manufacturer number 263, on the airfield at Cape Gloucester, New Britain. He stared in frustration at an engine that refused to start.

For eight months this aircraft had been his fighter. It wore the two white fuselage bands of the 2nd Chutai commander, an eagle emblem beside the cockpit, and red four-pointed stars stenciled over the wing gun ports. In it, he had flown dozens of hard combat sorties over New Guinea.

Now, on the morning he needed it most, the temperamental Kawasaki Ha-40 engine would not even fire.

At just 25 years old, Tōguchi was already commander of the 2nd Chutai of the 68th Sentai, credited with 19 aerial victories. Since April, when his unit converted from the nimble Nakajima Ki-27 to the heavier, more modern Ki-61, he had mastered the new fighter’s quirks and strengths.

The 68th Sentai was the first Imperial Japanese Army Air Force unit to receive the Ki-61. Deployed to Wewak in June, it bounced between rough, hastily constructed airstrips as the New Guinea campaign intensified. Cape Gloucester, at the northwestern tip of New Britain and about 230 miles from Rabaul, served as a forward base for fighters trying desperately to blunt relentless American bombing.

By late December, the tactical situation had collapsed. Intelligence reports warned that U.S. Marines were preparing a major amphibious assault on Cape Gloucester. Japanese command ordered all serviceable aircraft withdrawn to Rabaul immediately.

Tōguchi’s beloved No. 263, however, was no longer serviceable.

The Ha-40 had been giving trouble for weeks—burning oil, overheating even at idle. The day before, it had misfired at altitude during a patrol, forcing Tōguchi to abort early. Mechanics had worked through the night, checking spark plugs, valve clearances, magnetos—whatever they could touch with the limited tools and no spare parts.

It wasn’t enough. At dawn, the engine still refused to start.

At 0640, Tōguchi made the hard decision: he would evacuate in another Ki-61. Number 263 would stay behind, hidden in the jungle and left to its fate. Everyone understood what that meant.

Mechanics taxied the fighter off the strip into a stand of palms, covered it with cut branches, and then departed with the remaining ground crews. At 0700, Tōguchi took off in a different Ki-61 for Rabaul, leaving behind the aircraft that had carried him through months of combat.

For four days, the abandoned fighter sat under the canopy, silent and unseen.

On December 30th, 1943, U.S. Marines of the 1st Marine Division seized Cape Gloucester in the opening of Operation Backhander. A patrol soon discovered the carefully concealed Ki-61.

To the Marines, it was a prize.

The aircraft was almost perfectly intact. The fuselage command bands were still visible under the foliage. The eagle emblem still marked it as a leader’s mount. Unlike most captured Japanese fighters—usually destroyed in combat, burned out, or wrecked—this one had everything: engine, instruments, weapons.

It was identified as a Ki-61-I Ko, an early production version built at Kawasaki’s Kagamigahara plant in April 1943. Construction number 263; uncoded serial 163. It carried two Ho-103 12.7 mm machine guns in the nose and two Type 89 7.7 mm machine guns in the wings.

On January 2nd, 1944, Technical Air Intelligence Unit personnel arrived and began a meticulous examination. They measured control travel, photographed every angle, tested the engine, traced fuel and oil lines, mapped the electrical system. Every detail was recorded.

For a year and a half, Allied pilots over New Guinea had faced this mysterious new Japanese fighter—nicknamed “Tony.” Many believed it was a German Bf 109 or an Italian Macchi fighter in Japanese markings. Now, for the first time, the Allies had a complete, undamaged example.

The truth was revealed: this was a wholly Japanese airframe, powered by a license-built Daimler-Benz DB 601 derivative—the Kawasaki Ha-40.

Its deep, narrow fuselage and relatively small wings gave it high wing loading. That translated into good speed, strong diving performance, and the ability to absorb battle damage—but at the cost of tight turning ability. Its wing-mounted radiators and nose-heavy balance matched combat reports: it could outrun and outdive most Japanese fighters and take more punishment, yet struggled in low-speed dogfights.

In March 1944, the captured Ki-61 was shipped to Eagle Farm near Brisbane, Australia. There, technicians finally identified the original problem: a failed magneto. With that replaced, the Ha-40 ran normally.

American test pilots flew No. 263 extensively. Compared with captured Zeros and Oscars, the Ki-61 was faster in level flight and dives, accelerated better, and hit harder with its guns—but it turned more poorly and demanded careful energy management. It excelled in hit-and-run slashing attacks, but became vulnerable if forced into a slow turning fight.

These findings matched what Allied pilots had already learned the hard way. The airplane confirmed their tactical instincts.

The intelligence value of No. 263 went beyond performance charts. Wear patterns showed the strain of Japanese maintenance and supply. Paint and markings revealed unit structure and practices. The engine’s condition hinted at the limits of Japanese industry.

By May 1944, the aircraft had been repainted in U.S. markings and re-designated XJ0000003 for further testing. Lessons from this single fighter helped refine Allied tactics against Ki-61s across the Pacific.

Later, the aircraft was shipped to Naval Air Station Anacostia near Washington, D.C., and flown against American navy fighters. Against the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair, the Ki-61 was clearly outclassed: slower, with poorer climb and overall performance.

Testing continued into early 1945. On July 2nd, No. 263’s story ended when the engine failed in flight over North Carolina due to metal contamination. The aircraft crashed and was written off—brought down, ironically, by the same chronic Ha-40 problems that had first grounded it at Cape Gloucester.

By then, its intelligence value had already reshaped Allied understanding and doctrine.

Captain Tōguchi never knew what became of his airplane.

After departing Cape Gloucester on December 26th, he returned to frontline duty. Just days earlier, on December 21st, he had flown an escort mission from Boram near Wewak, protecting Ki-48 bombers attacking American positions at Arau. The formation was intercepted by P-38 Lightnings.

In the ensuing dogfight, Tōguchi’s Ki-61 was hit repeatedly and caught fire. He stayed with his burning aircraft and crashed near Hansa Bay. At 25, with 19 confirmed victories, he vanished without a trace. His body was never recovered.

The 68th Sentai itself did not last much longer. Hammered by engine failures, lack of spare parts, primitive maintenance facilities, and overwhelming Allied air power, it was effectively destroyed by March 1944. Survivors were reassigned or pushed into ground combat as Japan’s position in New Guinea collapsed.

Only two pilots of the Sentai achieved notable success on the Ki-61: Tōguchi, and Lieutenant Mitsuyoshi Tsurui, both originally trained on the agile Ki-27 and initially uncomfortable with the heavier, more demanding Ki-61 until they mastered it. Tsurui survived longer, later fighting in the Philippines and finishing the war with 23 victories, becoming one of the most successful Ki-61 pilots.

Their experience highlighted the Ki-61’s true character. In the hands of skilled, adaptive pilots, it could be deadly. But its unreliable engine and Japan’s collapsing logistics strangled its potential.

By late 1943, when aircraft No. 263 was left hidden under palm fronds, Japan’s broader strategic decline was already irreversible. American industry was flooding the Pacific with modern fighters and bombers. Japanese pilots were dying faster than they could be replaced. The Ki-61 remained respectable, but rapidly slipped into obsolescence.

Yet in 1944, the Ki-61 found a grim new role with the arrival of the B-29 Superfortress over Japan.

As one of the few Japanese fighters able to reach B-29 altitudes, the Ki-61 became central to home defense. Nowhere was this more evident than in the famed 244th Sentai, based at Chōfu Air Base and led by the bold, charismatic Captain Teruhiko Kobayashi.

As B-29 raids intensified, Japanese authorities formed specialized ramming units. Though not officially “kamikaze,” the missions were scarcely less dangerous. Pilots were expected to ram a B-29’s tail or wing, then bail out before their own aircraft broke apart. The odds of survival were low.

Within the 244th, the Hagakure Tai ramming flight was formed. On December 3rd, 1944, First Lieutenant Tooru Shinomiya led a high-altitude sortie, then dove his stripped-down Ki-61 into a B-29’s vertical tail. He tore the bomber’s empennage off, sending it down in flames—then fought to escape his crippled fighter, bailed out at 12,000 feet, and survived.

Other pilots rammed B-29s the same day and lived. Their shattered Ki-61s were displayed in Tokyo as propaganda symbols of desperate national resistance. The three pilots became the first recipients of the Bukōshō, Japan’s highest wartime award for valor.

Through late 1944 and early 1945, the 244th Sentai continued both ramming attacks and conventional interception missions, claiming 73 B-29s destroyed. The number was exaggerated, but their impact was real. Kobayashi—Japan’s youngest Sentai commander—often led from the front and even carried out a ramming attack himself in January 1945, destroying a B-29 and surviving to fly again the next day.

Other pilots surpassed even his tally, including Captain Nagao Shirai with 11 B-29 kills. Despite heavy losses, chronic fuel shortages, and disintegrating logistics, the 244th Sentai kept fighting into mid-1945. By April, they began to receive the new Ki-100, a radial-engined development of the Ki-61 that finally fixed the Ha-40’s fatal flaws.

In July 1945, Kobayashi led his men in a daring, unauthorized low-altitude fight against Hellcats attacking Yokohama—an action that nearly ended in his court-martial, but he was personally pardoned by the Emperor. Kobayashi survived the war, later flying jets in the new Japan Air Self-Defense Force, before dying in a crash in 1957 at just 36.

The Ki-61’s story mirrors Japan’s air war as a whole: early promise, technical ambition, courageous pilots—undone by industrial weakness, poor logistics, and strategic overreach. On paper, the Ha-40 engine was a strength. In reality, it became the aircraft’s greatest liability. Japan never had the spare parts, trained ground crews, or industrial capacity to keep it reliable.

By mid-1945, Japanese air power had all but collapsed, and the once-modern Ki-61 was outmatched by every advanced Allied fighter in the sky.

Yet the pilots who flew it—Tōguchi with his 19 victories, Tsurui with 23, Kobayashi and his B-29 kills, the Bukōshō recipients of the 244th Sentai—left behind a record of adaptability, courage, and tactical ingenuity under impossible conditions.

They fought for an ultimately unjust cause, in service of a regime responsible for grave atrocities. But as individuals, they often showed skill, bravery, and humanity in the face of near-certain death. Their story is complicated—and deserves to be remembered without romanticizing their cause or denying their personal courage.

The Ki-61 deserves recognition not as a war-winning weapon, but as a remarkable fighter designed under crushing constraints and flown by men who wrung every last ounce of performance from it.

Manufacturer number 263—abandoned at Cape Gloucester, captured intact, tested exhaustively, and finally destroyed by the same engine flaws that doomed it in combat—stands as a symbol of Japan’s ambitious but unsustainable attempt to match Allied air power.

Today, only a handful of Ki-61s survive in museums, silent metal witnesses to a history shaped by innovation, desperation, and sacrifice. The men who flew and maintained them are almost all gone.

But their stories remain, woven into the vast and troubled tapestry of the Second World War.

News

How One Welder’s “Ridiculous” Idea Saved 2,500 Ships From Splitting in Half at Sea

January 16th, 1943. Portland Harbor, Oregon. The morning was calm and bitterly cold, the kind of cold that made steel…

How One Cook’s “INSANE” Idea Stopped U-Boats From Detecting Convoys

March 17th, 1943. North Atlantic, roughly 400 miles south of Iceland. Convoy HX 229 forces its way through 15-foot winter…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Technical Sergeant James McKenna knelt beneath the left wing of a P-38 Lightning…

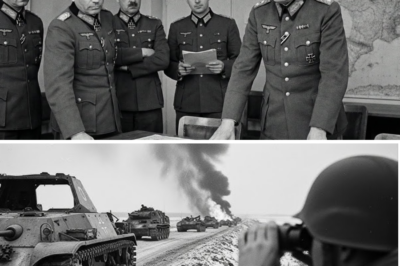

How German High Command Reacted When Patton Turned His Army 90° in a Blizzard

“Impossible. Unmöglich.” That was the mood inside German high command when the first reports came in. On December 19, 1944,…

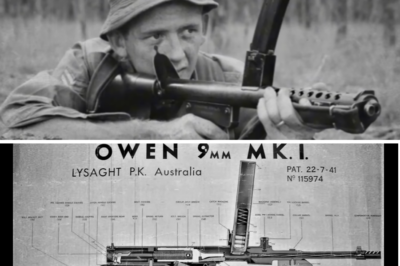

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

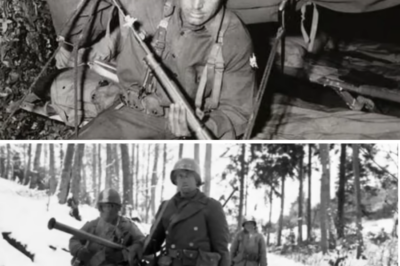

They Banned His “Rust Lock” Rifle — Until He Shot 9 Germans in 48 Hours

THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb…

End of content

No more pages to load