Chapter 1

I work as a waitress at one of the most expensive restaurants in New York City. Most nights I serve celebrities, CEOs, people who spend more on a single meal than I make in a week. I’ve learned how to glide between tables without being noticed, how to smile and make eye contact just long enough, how to pretend it’s normal to carry a steak that costs more than my rent. I’m professional. I don’t ask for autographs, don’t sneak photos, don’t make a scene. I am, as my manager likes to say, “visible but invisible.” Three months ago, on a Friday night in late October, I was nine hours into a double shift at Cipriani in Midtown. My feet burned, my lower back ached, and my ponytail felt like it was trying to pull my scalp off, but the dining room was full and humming and there was no room for being tired. The kind of crowd you get in Manhattan when the markets are up and the city feels like it owns the world—models laughing too loudly, men in suits talking about deals and mergers, couples stealing photos of themselves against the glittering night outside the windows. I was balancing a tray of empty plates when Josh, our floor manager, intercepted me with that look he gets when something big is about to happen. “Lucia,” he said in a low voice, “table twelve, VIP. He asked for privacy and the best server we have. That’s you.” I shifted the tray to one hand. “Who is it?” “Adrien Keller.” I knew the name. Everyone did. Worth $4.2 billion, according to some article I’d read on my lunch break once. Tech mogul, self-made, German immigrant who’d built a software empire from nothing and somehow managed to look bored in every photo I’d ever seen of him. The kind of man people wrote think pieces about—visionary, ruthless, genius, lonely. “He’s eating alone?” I asked before I could stop myself. “Apparently,” Josh said. “Private corner table, no paparazzi, no fuss, just service. Don’t hover, but don’t disappear. You know the drill.” “Got it.” I dropped the tray, picked up a water pitcher and a basket of bread, and walked to table twelve. It was tucked into the back corner, half shielded by a frosted glass partition, far enough from everyone else that you could pretend the rest of the restaurant didn’t exist. Adrien Keller sat with his back to the wall, facing the room. Mid-forties, maybe. Dark blond hair just starting to go gray at the temples, the kind of gray that looked intentional and stylish instead of tired. He wore a charcoal suit with no tie, top button of his shirt undone. Not flashy, no watch the size of a small planet, no visible logo, nothing screaming for attention. But he drew attention anyway. His posture was straight, his presence filling the small space around him, and there was something in his face—tired, yes, but also…sad. That was the word that came to mind. Not annoyed, not stressed, just quietly sad. I slipped into my role. “Good evening, sir. My name is Lucia. I’ll be taking care of you tonight. Can I start you off with something to drink?” He looked up at me, and up close, the sadness was even more obvious. His eyes were a pale, clear blue that might’ve been sharp once but now looked like they’d seen too much. “Red wine,” he said after a beat. “Whatever you recommend.” “The Barolo is excellent,” I said. “Full-bodied, smooth, pairs well with most of our mains.” “That’s fine.” I poured water into his glass, set down the bread, and stepped back, giving him enough space to breathe. He didn’t reach for the bread. He just stared out at the window where the Manhattan skyline glowed and reflected in the glass, like he was watching a life he wasn’t part of anymore. Wealthy people eating alone have always made me sad. You have everything, and yet you’re in a crowded, beautiful restaurant on a Friday night with no one to talk to but your phone and your own thoughts. What’s the point of all that money if you end up alone at table twelve? I brought the wine, presented the bottle, poured a taste. He nodded without really looking, so I filled his glass. He ordered a filet mignon, medium rare, with asparagus and potatoes. Simple, no substitutions, no questions about ingredients or calories or provenance. “Thank you,” he said quietly, and his voice was surprisingly soft. “Of course, sir. I’ll have that out shortly.” I turned to leave, notes already forming in my head—table twelve, fast but not rushed, check back in a few minutes—but then I saw it. His left hand rested near the stem of his wineglass, fingers long, nails neatly trimmed. As he reached for the glass, his sleeve pulled back a little, just enough to expose his wrist. There, on the pale inner side, was a tattoo. Small, delicate, but unmistakable. A red rose, thorns curling and twisting into the shape of an infinity symbol. My breath caught so hard I almost choked. I know that tattoo. I have known that tattoo my entire life. My mother’s left wrist bears the exact same design. I grew up looking at it: when she stirred a pot on the stove, when she brushed my hair as a child, when she reached for my hand to cross the street, when she hugged me, when she cleaned strangers’ houses for a living. A red rose with thorns twisting into an infinity sign, the lines now faded with age, the red no longer bright but still very much there. When I was seven, I asked her about it. “Mama, what does that mean?” I remember her pausing, the dishcloth in her hand dripping water into the sink. “It’s from a long time ago, tesoro,” she said. “Before you were born.” “But what does it mean?” I asked. She smiled sadly, tracing the rose with her thumb. “It means love is beautiful,” she said, “but it hurts, and it lasts forever.” “Did you love someone?” I asked. “I love you,” she answered. “Someone else?” Her smile faded into something distant. “Once,” she said quietly. “A long time ago.” “My dad?” I blurted out. She pulled her hand back, wiped the counter a little too hard. “He’s gone. That’s all. Now go play.” And that had been the end of it. Every time I brought it up after that, she’d change the subject, tell me to do my homework, ask if I’d eaten. Eventually I stopped asking. But I never stopped wondering. And now, in this restaurant where entrees cost more than our weekly grocery budget, a billionaire I’d never met had the exact same tattoo in the exact same place. What were the odds? I must have been staring, frozen, because he noticed. He glanced down at his wrist, then up at my face. “Is something wrong?” he asked. I swallowed. This was a terrible idea. It was unprofessional, invasive, against everything I’d been trained to do. But my heart was pounding so hard I could feel it in my throat. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I shouldn’t say anything. It’s not professional, but…” I took a breath. “This is going to sound strange, but my mother has a tattoo exactly like that. Same rose, same thorns, same wrist.” Everything about him went still. His wineglass hovered halfway between the table and his lips. “What did you say?” he asked, voice low. “My mother,” I repeated, suddenly unsure. “She has that exact tattoo. I’ve asked her about it my entire life. She never tells me what it means. She just says it’s from before I was born.” His throat worked like he had to remind himself how to swallow. “What is your mother’s name?” he asked. “Julia,” I said. “Julia Rossi. Why do you—” The wineglass slipped from his fingers. It hit the edge of the plate, bounced, then crashed to the table and exploded, red wine splashing across the white tablecloth like blood. The restaurant noise seemed to drop away. For a second, it was just the sound of liquid spreading and my own pulse roaring in my ears. “Julia,” he whispered. I snapped into motion. “I’m so sorry, sir,” I said, grabbing napkins, blotting at the spreading stain before it dripped into his lap. “Let me get you another glass, on the house, of course, I—” “How old are you?” he interrupted. He wasn’t looking at the ruined tablecloth. He was staring at me like I’d climbed out of his past. “I’m twenty-four,” I said slowly. “Sir, are you okay?” “Twenty-four,” he repeated, and I could see him doing math in his head, his gaze briefly unfocused. “Where is she?” His voice was raw. “Where is Julia?” “She’s…she’s in the hospital,” I said, thrown by his intensity. “She’s sick. Do you know my mother?” He pushed his chair back so fast it scraped harshly against the floor. People at nearby tables turned their heads. He pulled his wallet out and threw a handful of bills onto the table without looking. “I have to go,” he said. “I’m sorry.” “Wait, sir, your food is on the way, you don’t have to—” “Keep the money,” he said. “I have to go.” And he did. He walked straight out, leaving behind a shattered wineglass, a ruined tablecloth, a pile of crisp hundred-dollar bills, and me, standing there with wine on my hands and absolutely no idea what had just happened. When my shift finally ended, it was almost two in the morning. I took the subway home, replaying the scene over and over, the broken glass, the way he’d said my mother’s name, like it had cut him. Our apartment in Queens was dark when I unlocked the door. I dropped my bag, kicked off my shoes, and sat on the edge of the sagging couch. My uniform still smelled like steak and spilled wine. I pulled out my phone. Me, 2:07 a.m.: Mama, do you know someone named Adrien Keller? I stared at the screen, willing the three dots to appear, but nothing did. She was probably asleep; the pain meds and the chemo knocked her out early most nights. After a minute, I opened a browser and typed his name. Dozens of hits came up—Forbes lists, TechCrunch interviews, photos of him at galas and conferences and charity events, always in the same kind of perfectly tailored suit, always alone. That struck me. Never a wife on his arm, never a girlfriend, never the same beautiful woman twice. Some article called him “tech’s most eligible bachelor.” Another quoted him from five years ago: I was in love once, a long time ago. It didn’t work out. I’ve never found that again. I studied a photo of him onstage at some conference, sleeves rolled up. There it was, on his left wrist—the rose, the thorns twisted into an infinity symbol. The same as my mother’s. My heart felt too big for my chest. What happened between you and my mother? I wondered. Who were you to her? Who are you to me? And then, because it was late and I was exhausted and my life already felt like it was falling apart, I forced myself to put the phone down. Tomorrow, I thought. Tomorrow I’ll ask her. If she answers. If she can. Because before the tattoo and the billionaire and the shattered glass, there was the worst part of all: my mother is dying. Breast cancer, stage four. It’s in her lymph nodes and liver. The doctors at Mount Sinai gave her a year. That was three months ago. She’s been through chemo, radiation, two clinical trials. Even with insurance, the copays are crushing us. My mother, Julia, has worked as a housekeeper for rich families in Manhattan and Brooklyn for twenty-four years—my whole life. She cleans marble kitchens and glass showers and bedrooms with sheets that cost more than we spend on groceries in a month. Six days a week, sometimes seven. She never complains. She never asks for help. She just works. Until she couldn’t. Until the cancer spread and the treatments weakened her and suddenly the woman I thought was made of iron couldn’t climb stairs without stopping to breathe. So I work. I work breakfast and dinner shifts, and sometimes lunch if they’re desperate. I bring home maybe four hundred dollars in tips on a really good night, closer to two hundred on an average one. It’s not enough. Not for New York, not for rent, not for hospital bills. But it’s all I have. That night, as I lay in bed listening to the radiator hiss, staring up at the ceiling of the tiny bedroom I’d grown up in, I had no idea that the man with my mother’s tattoo was about to rip open a secret that had been waiting in the dark for twenty-five years.

Chapter 2

Visiting hours at Mount Sinai start at ten a.m., but I got there at nine-thirty anyway. The oncology wing always smells faintly of bleach and something metallic, like fear has its own scent. My mother’s room—407—had a small window that faced another building. The light that slipped in was thin and tired. When I pushed the door open, she was awake, sitting up in bed, a paperback novel open but clearly unread in her lap. The chemo had taken her hair months ago, leaving her head smooth and oddly delicate. Her cheeks were hollow, her skin pale and almost translucent, but when she saw me, her face lit up. “Tesoro,” she said, her Italian accent softening the edges of the word. “You didn’t have to come so early.” “I always come on Saturdays,” I said, leaning down to kiss her forehead. Her skin was warm, a little too warm. “How are you feeling?” She shrugged one shoulder, the IV line tugging faintly when she moved. “Tired. But the new medication helps with the nausea. I only threw up twice.” She said it like it was a victory. Maybe it was. “That’s good,” I said. I pulled the chair closer to her bed and sat down, setting my bag at my feet. We talked about small things first—the nurse who’d tried to practice her Italian on my mother and mixed up two phrases, the tasteless soup on the lunch tray, the sitcom reruns that played endlessly on the tiny mounted TV. I watched her talk, watched the way her hands still moved when she told a story, even though the rest of her body seemed exhausted. The tattoo on her wrist peeked out from under the hospital gown, the rose and thorns faded but clear. I’d seen it so many times it felt like part of the background of my life. Now it felt like a spotlight. When there was a break in the conversation, when she reached for her water cup and took a slow sip, I said as casually as I could, “Mama, do you know someone named…Adrien Keller?” The effect was immediate. She went still, the plastic cup halfway to her lips. Water sloshed inside. Her eyes lifted to mine, wide and suddenly afraid. “Why do you ask that name?” she whispered. Relief and dread collided in my chest. “He came into the restaurant last night,” I said. “He was at one of my tables.” Her free hand moved instinctively to cover her wrist, as if she could hide the tattoo I’d already seen a thousand times. “He has a tattoo exactly like yours,” I continued. “Same rose. Same thorns. Same wrist.” The color drained from her face so fast it scared me. “Adrien was there? At your restaurant?” Her voice shook. “You do know him,” I said. “He’s famous, you know. Billionaire famous. Mom, who is he?” She reached for the hospital bed controls and raised herself up a little higher, like she needed more air. “What did he say? Did he—” “He saw my tattoo comment, asked your name,” I said. “When I said ‘Julia Rossi,’ he dropped his wineglass and basically ran out. He looked like he’d seen a ghost. So, I’m asking you again. Who is he?” She pressed her fingers to her mouth, and to my horror, tears began to spill down her cheeks. I rarely saw my mother cry. She cried when my grandmother died back in Italy, quietly, alone in the kitchen. She’d cried when she got her diagnosis, but only once, and then she’d dried her eyes and made a list of things to take care of before chemotherapy started. Seeing her cry now, openly, broke something in me. “He found me,” she said in Italian, voice cracking. “Dopo tutti questi anni. After all these years, he found me.” “Mama,” I said, my throat tight. “What are you talking about?” She wiped her cheeks with shaking fingers. “I knew him as Adrien Keller, but he was just Adrien then. We were…we were in love. Twenty-five years ago. Before you were born.” The room tilted. “What happened?” I asked. “What happened between you?” “I had to leave,” she said. “Go back to Italy. My nonna had a stroke. I promised him I would come back in six months. I swore it. I tried, Lucia. I tried so hard. But when I came back, he was gone. I looked for him everywhere. I thought…” She took a breath that sounded like it hurt. “I thought he had forgotten me. Moved on. Found someone else.” “And the tattoo?” I whispered. She touched her left wrist with something like reverence. “We got them together,” she said. “The week before I left. He said, ‘Even when we’re apart, we’ll have this. Proof that we existed, that what we had was real.’ He designed it himself.” My chest ached. “I didn’t know,” I said. I didn’t know any of this, and suddenly my whole life felt like it had a secret foundation I’d never seen before. “I need to see him,” she said, her eyes locking onto mine. “Lucia, please. I need to see him.” “I don’t have his number,” I said helplessly. “I don’t know how to reach him. He left the restaurant like it was on fire.” “You said he is famous now,” she insisted. “There must be a way. Please, tesoro. I don’t have much time left. I need to see him. I need him to know I never forgot.” I nodded, even though I had no idea what to do. “I’ll try,” I said. It was the only promise I could make. On my way out of the hospital, I called the restaurant. Josh picked up on the second ring. “Cipriani, this is Josh.” “It’s Lucia,” I said. “Listen, did Mr. Keller leave any kind of contact info last night? A card, a number, anything?” “No,” Josh said. “No, but Lucia—actually, someone’s here asking for you.” My heart jumped. “Who?” “Some guy in a suit,” he said. “Says his name is Thomas Beck. He’s Keller’s lawyer. He wants to talk to you.” I stared at the elevator doors in front of me as they slid open and shut. “I’m at the hospital,” I said. “With my mom. Can he come here?” “Hold on,” Josh said. I heard muffled conversation, a low male voice, then Josh again. “He says he’ll be there in thirty minutes.” Thomas Beck looked exactly like a lawyer from a movie. Mid-fifties, silver hair neatly combed back, expensive gray suit, polished shoes, a leather briefcase that probably cost more than my entire wardrobe. He found me in the hospital cafeteria, sitting at a table with a half-eaten muffin and cold coffee. “Ms. Rossi?” he asked politely. “Lucia?” “That’s me,” I said, standing. “You’re Mr. Beck?” “Please, call me Thomas.” His smile was kind, not the sharp, assessing look I expected. He gestured for me to sit, then took the chair across from me and set his briefcase down. “I represent Mr. Keller. He asked me to locate you and inquire after your mother.” “Is he okay?” I asked before I could stop myself. “He seemed…upset when he left last night.” Thomas’s gaze softened. “He’s been upset for twenty-five years,” he said. “Last night was the first time he had hope.” He pulled a tablet from his briefcase and opened a notes app. “May I ask you a few questions about your mother?” “Yes,” I said, sitting up straighter. “Her full name?” “Julia Rossi. R-O-S-S-I.” “Age?” “Forty-eight.” “Her medical condition?” I swallowed. Saying it out loud always made it feel more real. “Breast cancer. Stage four. It’s in her lymph nodes and liver. She’s being treated here, at Mount Sinai. Oncology, room 407.” “Prognosis?” he asked gently. “Less than a year,” I said. “Maybe less than that. The doctors won’t say exactly, but…it’s not good.” He typed quickly. “And you said she knows Mr. Keller?” “She says they were in love twenty-five years ago,” I said. “She had to go back to Italy because her grandmother was dying. She promised she’d come back. When she did, he was gone. She thought he’d moved on.” Thomas’s hand paused above the screen. “He didn’t move on,” he said quietly. “He spent five years looking for her. He thought she had decided to stay in Italy. That she chose her family over him. They both thought the other had given up.” The unfairness of it made my eyes sting. “Exactly,” I whispered. “She thought the same thing.” Thomas closed the tablet with a final tap. “Adrien wants to see her,” he said. “With your permission.” Relief flooded me so fast it made me lightheaded. “She wants to see him, too,” I said. “When?” “Now,” he said. “Today. As soon as possible. You said she doesn’t have much time.” “She doesn’t,” I said. “She really doesn’t.” “Understood.” He stood, gathering his things. “I’ll bring him this afternoon.” Three hours later, there was a knock on the door of room 407. My heart kicked against my ribs. I stood up, smoothed my hair back, and opened it. Adrien stood in the hallway. Same charcoal suit from the night before, but this time his tie was knotted, his hair combed back neatly, like he’d made an effort and then undone it with his hands on the drive over. His eyes looked worse—red-rimmed, as if he hadn’t slept. “Is she…?” he began, voice low. “She’s awake,” I said. “She knows you’re coming. But Mr. Keller—” “Adrien,” he said. “Please. Just Adrien.” “Adrien,” I corrected, feeling weirdly formal. “She’s very sick. She looks different than you remember. The chemo…” “I don’t care what she looks like,” he said, and there was a fierceness in his tone that startled me. “I just need to see her.” I stepped aside. He walked in. My mother was sitting up, pillows propped behind her. She’d insisted on putting on a little lipstick earlier, hands trembling as she applied it. Now, as she looked toward the door, the tube slipped from her fingers and rolled to the blanket. For a moment, she seemed frozen. Then she whispered, “Adrien.” He crossed the room slowly, like he was afraid she might vanish if he moved too fast. He sat in the chair beside her bed, his shoulders suddenly hunched, all that billionaire composure gone. He took her left hand gently, his thumb brushing over the faded rose on her wrist. “Julia,” he said, and his voice cracked. For a long time, they just looked at each other. Twenty-five years of questions, regrets, and what-ifs hung in the silence between them. Then, at the same time, they both began to cry. I slipped out quietly and closed the door behind me, leaving them to whatever conversation they’d been waiting decades to have. I sat on a plastic chair in the hallway, staring at the scuffed linoleum floor, listening to the faint sounds from inside—murmured words, laughter that sounded like it hurt, long stretches of silence. My mind spun with questions. Who had he been to her? Who had she been to him? And where did I fit into all of this? Two hours and seven minutes later—yes, I counted— the door opened. Adrien stepped out, his hand still on the doorknob, like he needed the support. His face was pale, eyes red and puffy. He looked like someone who’d just watched his favorite city burn down and then rebuilt it with his bare hands in the same afternoon. “Is she okay?” I blurted, standing up. “Is my mother—” “She’s okay,” he said quickly. “She’s…she’s stronger than anyone I’ve ever met.” His gaze moved to me, and something in his expression shifted. It was the way he looked at me that made my stomach sink. He wasn’t just seeing me now; he was studying me, memorizing, comparing. “Adrien?” I asked, my voice suddenly small. “What’s wrong?” “Lucia,” he said quietly. “I need to talk to you. Right now. Somewhere private, if that’s possible.” A cold wave of dread rolled through me. “Um…sure,” I said. “There’s a cafeteria downstairs.” “That will do.” We walked in silence. The fluorescent lights in the stairwell hummed, and every step felt heavier than the one before. My mind raced through possibilities—she was worse than she’d told me, she’d changed her will, he was going to offer money, he was going to disappear. None of those guesses came close. In the cafeteria, we bought coffee we didn’t drink and sat at a corner table away from the vending machines and noise. Adrien’s hands trembled slightly when he set his cup down. He took a breath, let it out. “You’re scaring me,” I said, my voice too loud in the empty space. “What did my mother tell you?” “Lucia,” he said, and my name sounded different in his accent, softer. “When is your birthday?” Of all the questions I expected, that was not one of them. “What?” “Your birthday,” he repeated. “When is it?” “March fifteenth,” I said slowly. “Why?” “What year?” “Two thousand,” I said. “Adrien, what is going on?” He closed his eyes briefly, like the answer physically hurt. When he opened them again, they were full of tears. “Your mother just told me something,” he said. “Something she has kept hidden for twenty-four years.” My heart hammered so hard it hurt. “What?” I whispered. “When she went to Italy in 1999,” he said, “she didn’t know she was pregnant. She found out about a month after she arrived. In August.” The world tilted under my chair. “Pregnant with you, Lucia. She was pregnant with you.” I couldn’t speak. Couldn’t breathe. The cafeteria, the hospital, the hum of the refrigerator—all of it faded into a blur behind a single thought crashing through my brain. No. No. No. “She came back to New York in January 2000,” he continued gently. “Seven months pregnant. She went to my old apartment. I was gone. I had moved in December. She looked for me for two weeks. She couldn’t find me. And then”—his voice broke—“March fifteenth, 2000. You were born at this hospital. She was completely alone.” He swallowed hard. “I was working three subway stops away. And I had no idea.” My mouth was dry. “Are you saying…” I couldn’t finish the sentence. “I’m saying,” he whispered, “that we think…I’m your father.” The words echoed in my skull like someone had shouted them through a tunnel. We think I’m your father. My lungs forgot their job. The hands on the clock above the vending machines seemed to freeze. For a second, I genuinely thought I might pass out. “No,” I said finally, shaking my head. “No. My mother said my father was some guy from Italy who left when she got pregnant.” “She said that,” he said softly, “because she couldn’t find me. She thought I had moved on, that I’d abandoned her. She thought it was kinder to tell you he was far away than admit he might still be in the same city and just not want you.” His jaw clenched. “But I was here, Lucia. I have been here in New York for twenty-four years. Working. Building a life. Looking for her. I just didn’t know about you.” “You didn’t know I existed,” I repeated. “I had no idea.” His voice shook. “If I had known—if I had found her when she came back—everything would have been different. I would have been there for your birth. Your first steps. Your first day of school. All of it. But I didn’t know. I swear to you, I didn’t know.” I pushed my chair back abruptly; the metal legs screeched loudly across the floor. “I need to talk to my mother,” I said, my voice trembling. “I need to hear this from her. Right now.”

Chapter 3

My mother was waiting for me when I slipped back into room 407. Her cheeks were still damp, eyes swollen, but when she saw my face, her expression crumpled in a new way. “He told you,” she said quietly. I pulled the chair close to her bed and sat, my legs suddenly heavy. “Yeah,” I said. “He told me.” “Are you angry?” she asked, voice barely above a whisper. I thought about it. Anger was part of what I felt, but it wasn’t the whole story. I was hurt, confused, stunned, overwhelmed. Sad for the girl she’d been, for the man he’d been, for the child I’d been without knowing. “I don’t know what I am,” I admitted. “Honestly. But I need you to tell me everything from the beginning. No more secrets, no more half-truths. I need to understand.” So she told me. She started with 1999, with a restaurant in Brooklyn where she waited tables at night after cleaning houses during the day. “He was a regular,” she said, smiling faintly at the memory. “Came in once a week with a friend from work. They ordered beer and pasta, nothing fancy. He was quiet at first. Shy, even. He’d barely look at me when I came to the table. But his friend—Marko, I think—teased him. ‘Ask her out, man. You look at her like she’s the last glass of water in the desert.’” She laughed softly. “He blushed. Adrien always blushed easily back then.” She painted pictures as she talked—of Adrien in work boots and cheap jeans, working construction by day and teaching himself to code at night from library books; of herself, twenty-three, newly arrived from Italy with big dreams and bad English and a belief that hard work would fix everything. She described their first real conversation, when he came in alone one rainy Tuesday and sat at her section. How he’d stumbled over his words in broken Italian he’d learned from phrasebooks just so he could ask her if she liked living in New York. How she’d answered in equally broken English and both of them had ended up laughing. How, after she dropped off his check, he’d handed it back with a napkin tucked inside, his phone number scribbled on it. How she’d almost thrown it away because she was scared, then called him the next day anyway. They went on coffee dates, walks through Central Park on her days off, rides on the Staten Island Ferry just to feel the wind and see the Statue of Liberty from the water. He took her to Coney Island and won her a stuffed bear by missing every game and then buying it from the bored teenager who ran the booth. They were poor, both of them, but they were young and in love and New York felt like it belonged to them. “We used to sit on the roof of his building,” she said, eyes distant, “and look at the skyline and talk about the future. He said he was going to start a company one day. I told him I’d open my own cleaning business. We dreamed stupid, big dreams. And it all felt possible.” “When did you get the tattoos?” I asked. She looked down at her wrist, running her finger over the faded ink. “The week I left,” she said. “My nonna had her stroke in July. My mother called, crying, telling me she needed help. They didn’t have money for a nurse. I was the only one who could go. I didn’t want to leave him, but family is family. I told him I would come back by Christmas. Six months. He was angry at first. Hurt. But he said he understood. That he would wait.” The last week before she left was a blur of stolen moments—overnight stays, long conversations, plans made and remade. “We went to a tattoo parlor in the East Village,” she said. “He brought a sketch he’d drawn. The rose with the infinity thorns. He said, ‘Even when we’re apart, when we think this was all a dream, we’ll have proof on our skin that it was real.’ I was terrified of needles, but I did it anyway. He held my hand the whole time. Then it was his turn. He didn’t even flinch.” She smiled. “We walked out, our wrists wrapped in bandages, and he kissed me on the sidewalk and said, ‘Forever.’” “When did you find out you were pregnant?” I asked, my voice catching on the word. “In Italy,” she said. “At my parents’ house. I’d been home maybe a month. I was so tired, so nauseous. At first, I thought it was the stress. Then my mother said, ‘Julia, when was your last period?’” She laughed without humor. “We counted the weeks. Went to the clinic. I was six weeks along.” “Why didn’t you call him?” I asked, even though I already knew some of the answer. “I wanted to,” she said. “Phone calls were expensive. I could afford one every few weeks if I was careful. I tried. But when I called his apartment, the line just rang and rang. No answer. I wrote letters. I sent three over that summer. I never heard back. I didn’t have his new job address, only the restaurant and his apartment.” She shook her head. “Nonna got worse. I was working at a café and taking care of her at night. I kept telling myself, ‘I’ll tell him when I go back. I’ll tell him in person.’ I didn’t want to say it on the phone. It felt too big.” “And when you came back?” My voice was barely there. “I was seven months pregnant,” she said. “Huge. Exhausted. I went straight from JFK to his building. The landlord answered the door. He was old, hard of hearing. He said Adrien had moved in December. No forwarding address, no new number. I begged him to check. He got frustrated, said he didn’t remember. I went to the restaurant. They said he’d quit in November for some new job. They didn’t know where.” Her eyes filled again. “For two weeks, I walked the city with swollen feet and a belly out to here, asking everyone I could think of. His coworker had moved back to Germany. His roommate had gone to California. Everywhere I turned, the door was closed.” “And you gave up,” I said, not accusing, just trying to understand. “I was twenty-three, alone, pregnant, and scared,” she said. “I had five hundred dollars to my name. At some point I had to stop chasing a ghost and find a way to take care of you. I found a room with a friend, then an apartment in another neighborhood. I told myself if he had wanted to find me, he would have. That he had probably met someone else. That I had to stop hoping.” She wiped her eyes. “I told you your father was from Italy because it was easier than telling you he might be out there somewhere in this city, not knowing you existed. Easier than admitting I had failed you both.” I sat back, my head spinning. “I’m not angry at you,” I said finally. “I’m…sad. For all of us. For all the years you both lost.” She stared at me. “You’re not angry?” “How can I be?” I said. “You were young and scared and alone. You did what you had to do. You worked yourself into the ground to raise me. You gave me everything you could. That’s not something I can be angry about. You deserved help. You deserved a partner. He deserved to know. But neither of you did. You were both looking. You just…missed each other.” I shook my head. “That’s not your fault. That’s just cruel timing.” She squeezed my hand, her fingers thin and cold. “Ti amo,” she whispered. “I love you so much.” “I love you too, Mama,” I said. I left her room when a nurse came in to check her vitals and wandered until I found the stairwell. It was empty and quiet, smelling faintly of dust and industrial cleaner. I sat on the steps, pressed my elbows to my knees, and buried my face in my hands. I didn’t cry. I was past crying. I just sat there, trying to rebuild my entire sense of self around this new truth. Adrien found me there twenty minutes later. “May I join you?” he asked, his voice echoing faintly. I nodded. He sat beside me, leaving a respectable distance, his hands clasped loosely between his knees. We were silent for a while. “She told you everything?” he asked finally. “As far as I can tell,” I said. “About Italy, the baby, coming back, not finding you.” “Do you understand what happened?” he asked quietly. “Not forgive, necessarily. Just…understand.” I stared at my hands. “I understand bad timing,” I said. “I understand that you both tried and the universe decided to be cruel. But I’m still twenty-four and I just found out the story of my life is…different than I thought. I grew up believing my father was some mysterious guy from Italy who left before I was born. Now I know he was actually a man who lived in New York my whole life and just didn’t know I existed. That is…a lot.” “I know,” he said, his voice rough. “I know.” I took a breath. “Why did you move?” I asked. “In December 1999. She said she came back in January and you were gone. What happened?” He leaned forward, elbows on his knees, staring at the opposite wall like it could replay the past. “I got a job offer,” he said. “A startup in Midtown. They needed a programmer. It was more money than I’d ever made in my life. Real money. Enough to save, enough to maybe buy a ticket to Italy one day. I took it immediately, because I thought if I could save enough, I could go find her. Bring her back. Or stay there with her. Whatever she wanted.” He laughed bitterly. “I thought I was being responsible. I thought I was doing the right thing.” “So you moved closer to work,” I said. “Yes. I moved into a small room near the office. I was working sixteen, eighteen-hour days, sleeping on the couch half the time. I changed my phone number because the old one was a landline in my apartment, and I couldn’t afford to keep it and the new place. I got a cheap cell. I gave the landlord my new number and told him to pass it on if anyone asked. He said he would.” Adrien shook his head. “Apparently, he didn’t.” “Mom said she asked him,” I murmured. “He told her you hadn’t left any contact info.” “He was eighty-nine,” Adrien said. “He probably forgot. Or didn’t understand. Or…” He trailed off. “I left in early December. Started the new job December fifteenth. Your mother came back January tenth. She remembers the exact date.” He swallowed hard. “I missed her by one month. One month, Lucia. If I had waited, if I had visited the old building, if the landlord had remembered my number—any small thing—and you would have grown up with two parents.” He rubbed his face with both hands. “I have replayed that month in my head a thousand times. Every choice. Every moment. I have lived with that regret for twenty-five years.” I looked at him, at the way his shoulders sagged under the weight of his own blame. “You didn’t know,” I said quietly. “You both did what you thought was right. You both made decisions that made sense at the time. You both reached out and missed each other in the cracks.” “That doesn’t change what happened,” he said. “But it explains it.” We sat in silence for a moment. Then he cleared his throat. “I suppose…” He paused. “I suppose you’ll want a DNA test. To be sure.” “I think so,” I said. “I mean, I already know. I see it. In your face, your eyes, the tattoo. But yes. For legal things. Medical things. It would be good to have it on paper.” He nodded, and for the first time since I met him, he smiled, but it was small and shaky. “I agree. I need it for another reason, too.” “What’s that?” I asked. “Because if I let myself believe you’re my daughter,” he said quietly, “truly believe it, and then the test comes back negative…it would destroy me. I need the certainty so that when I let myself feel everything I want to feel, I know it’s real.” I understood. “Okay,” I said. “We’ll do the test.”

Chapter 4

The logistics happened fast, like everything else in Adrien’s world. When a billionaire moves, the universe seems to shift around him. Within a day, Thomas had arranged paternity tests through a private lab recommended by the hospital. They drew blood from me and from Adrien in a small examination room near oncology, the nurse politely pretending not to notice the way his hand shook as he signed the consent forms. “Results in three business days,” Thomas said. “But we can request a rush.” Adrien requested a rush. Of course he did. Those three days were some of the strangest of my life. I still went to work because bills didn’t stop just because your world turned inside out, but every time I carried a tray past table twelve, my chest tightened. I checked my phone constantly, expecting some kind of cosmic update. In between shifts, I went to the hospital. Sometimes Adrien was there when I arrived, sitting by my mother’s bed, their heads bent together in conversation like no time had passed at all. Sometimes they were laughing, sometimes crying, sometimes simply holding hands in silence. Once, I walked in and found them arguing—in Italian, no less—about who had given up first, who should have tried harder, who bore more of the blame. “You should have stayed one more month,” she snapped. “You should have told me you were leaving the apartment!” he shot back. “You knew where I worked, you could have left a message!” “You could have written to my parents in Italy!” “I didn’t have the address!” The nurse glanced at me, eyes wide. I leaned against the doorway, listening to the fury that only existed because they still cared so much. Finally, my mother slumped back against her pillows, exhausted. “We were children,” she said. “We did the best we could.” Adrien bowed his head. “I know,” he said. “I just wish our best had been enough.” On the third day, my phone buzzed as I walked up the hospital steps. Adrien. “The results are in,” he said without preamble. “Can you come to your mother’s room? I want us all to be together.” My throat tightened. “I’m already here,” I said. “I’ll be up in five minutes.” When I stepped onto the fourth floor, I saw him waiting outside room 407, an envelope in his hand. His fingers stroked the edge of it over and over, like he was afraid it might disappear. His face was composed, but the tension in his jaw gave him away. “Ready?” he asked. “As ready as I’ll ever be,” I said. We went in together. My mother straightened in bed, her hands twisting nervously in the blanket. The room was quiet except for the steady beep of her heart monitor and the distant sounds of hospital life out in the hall. Adrien stood at the foot of her bed, opened the envelope, and pulled out a stapled packet of papers. He scanned the first page, his eyes moving quickly, then slowing, then stopping. When he looked up, there were tears on his lashes. “It says,” he began, and his voice caught. He cleared his throat and tried again. “It says there is a 99.9% probability of paternity.” He turned fully toward me. “Lucia,” he said. “You’re my daughter.” I didn’t realize I was crying until I tasted salt. My mother let out a sob that was half relief, half grief. “Come here, tesoro,” she said, opening her arms. I went to her, burying my face in her shoulder like I hadn’t done since I was a child. I felt Adrien hesitate, hovering on the edge of the moment. “You can come too,” I said, my voice muffled. Something in his expression cracked. He stepped forward, wrapping one arm around both of us carefully, as if afraid he might break us. All three of us cried. It wasn’t a pretty, movie-style cry. It was messy and noisy and hiccupping and real. Twenty-four years of “what ifs” and “if onlys” poured out all at once. “What happens now?” I asked eventually, wiping my face on the sleeve of my sweater. Adrien laughed weakly. “Now?” he said. “Now I fix this. As much as I can.” He glanced at my mother. “I lost so many years. I’m not losing whatever time is left.” Over the next week, I learned what it was like to have someone with unlimited resources decide to fix your life. My mother’s oncologist, Dr. Hill, called me into her office. She wore a white coat and tired eyes and the kind of calm you only get from telling people terrible news for a living. “Miss Rossi,” she said, folding her hands on her desk. “I received a call this morning from someone claiming to represent a…Mr. Keller.” “Adrien,” I said automatically, then flushed. “Sorry. Yes. He’s an…old friend of my mother’s.” That was the safest label. “He wants to transfer your mother to a private facility,” Dr. Hill said. “Unlimited budget, access to experimental treatments. Is this legitimate?” “Yes,” I said. “It’s…real.” “An old friend with four billion dollars,” she mused, then smiled slightly. “He mentioned a particular clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering. An immunotherapy protocol that’s…well, very promising. But it’s not covered by insurance. It’s extremely expensive.” I chewed my lip. “He’ll pay,” I said. “He wants to help, and we…really need help.” Dr. Hill nodded slowly. “Then I’ll coordinate the transfer,” she said. “If your mother is willing. I won’t do anything without her consent.” “She’s willing,” I said. “She wants more time.” “Then let’s try to give it to her.” Two days later, my mother was moved to Sloan Kettering in an ambulance with Adrien riding in the front seat and me in the back, holding her hand. Her new room had a view of the East River, a private bathroom, a bigger TV. The nurses knew her name. The head of oncology himself came in to discuss the clinical trial. Words like response rate and progression-free survival and T-cells floated around us. All I heard was hope. Adrien paid for everything. The trial. The room. The specialized medications. He also, without asking, paid off her existing medical debt. One afternoon, Thomas handed me a neatly printed statement. “All outstanding balances have been settled,” he said. “Zero due.” The total at the top of the page—$140,000— made my stomach flip. “I can’t accept this,” I told Adrien that evening. “It’s too much.” We were sitting in the hospital lounge while my mother slept, a muted cooking show playing on the TV. “It’s not too much,” he said quietly. “It’s twenty-four years too late.” He didn’t stop there. He asked about my rent, my work, my education. When he found out I’d dropped out of NYU halfway through my junior year because we couldn’t afford tuition and medical bills at the same time, he looked genuinely pained. “You’re going back,” he said. “Excuse me?” “You’re going back to school,” he repeated. “You’ll finish your degree. I’ll pay for it.” “You can’t just—” “I can,” he said. “And I will. Your mother wanted that for you. This is one thing I can give you that doesn’t require a time machine.” “What about my job?” I asked, my chest tight with conflict. “Who’s going to pay rent?” “I am,” he said simply. “I can cover your rent for as long as you’re in school. You can work if you want to, but not because you’re desperate. You’ve been carrying this alone for too long.” I stared at him. Part of me wanted to say yes, throw myself into his protection and let him fix everything. Another part of me balked at the idea of accepting so much from a man who had just entered my life. “I don’t know if I can accept all of that,” I said. “It feels like…too much too fast.” He nodded, not offended. “It is a lot,” he said. “You don’t have to decide today. But know that it’s there. For you. For your mother. You don’t have to keep living on the edge of disaster.” Eventually, I said yes. Not because of the money itself, but because saying no started to feel like punishing all of us for something none of us had intended. I went back to NYU the following semester, commuting between classes and the hospital, my backpack full of textbooks and my heart full of complicated feelings. I quit my job at the restaurant with shaking hands. Josh hugged me and said, “I’m proud of you, kid. Go do something where people don’t snap their fingers at you for more bread.” The new treatments were brutal but effective. My mother’s hair began to grow back in patches, then fuzz, then soft curls. She gained a little weight, a little color. After three months, Dr. Hill—now coordinating with the team at Sloan—sat us down. “The tumors are shrinking,” she said, tapping a scan on the screen. “Not gone. But significantly smaller. We’re calling this a remission.” My mother started crying before the sentence was over. So did I. So did Adrien. “How long?” my mother asked when she caught her breath. “I can’t give you an exact number,” Dr. Hill said honestly. “But with continued treatment, we’re talking years, not months. Maybe many years.” “Years,” my mother repeated. She turned to Adrien, her hand seeking his. “We have years.” He squeezed her fingers. “We have whatever time you’ll give me,” he said. Watching them together was like watching two halves of a story finally bound into the same book. They spent hours talking about the past—comparing memories, filling in gaps. He told her about the early years of his company, the mistakes, the breakthroughs, the way success had felt oddly hollow when he didn’t have anyone to share it with. She told him about raising me on her own, about late nights doing laundry and early mornings cleaning bathrooms and the small victories that had kept her going. Sometimes, they’d both look at me at the same time with an expression I couldn’t quite decipher—something like wonder and guilt mixed together. “Our daughter saved us,” my mother said one afternoon when she caught me watching them. “If she hadn’t worked in that restaurant, if she hadn’t seen your tattoo—” “If you hadn’t gotten the tattoos in the first place,” I added. “If Nonna hadn’t called. If you hadn’t taken that job.” We all laughed. It was too much coincidence to untangle. Six months after that night at table twelve, Adrien proposed. Not in some grand public spectacle, not with cameras or articles or anything you might expect from a billionaire. Just in her hospital room, on a quiet Tuesday afternoon when the sky outside was a flat gray and the TV was off and I was sitting in the corner pretending to review notes for a midterm. He shifted in his chair, reached into his jacket pocket, and pulled out a small velvet box. “I should have done this twenty-five years ago,” he said, his voice shaking. “I should have put a ring on your finger and refused to let you get on that plane.” My mother’s eyes went wide, filling with tears instantly. “We were children,” she whispered. “We didn’t know.” “I’m not a child anymore,” he said. “And I know exactly what I want. Julia Rossi, will you marry me?” He opened the box. Inside was a simple gold band with a small diamond that caught the fluorescent light and turned it into something softer. My mother laughed and cried at the same time, her hand flying to her mouth. “I’m bald,” she said. “I’m in a hospital gown. I look terrible.” “You look like the woman I have been in love with for twenty-five years,” he said. “And I am not wasting another minute.” She reached for his hand. “Yes,” she said. “Si. Yes, I will marry you.” They were married a month later in the hospital chapel. It was small and bright, with wooden pews and a simple stained-glass window that cast colored light onto the floor. My mother wore a white dress that one of the nurses had helped her pick out, soft and flowing, with a little cardigan over her shoulders. Adrien wore a navy suit and a tie the color of the sky on a clear day. I stood beside my mother as her maid of honor and tried not to cry through the whole ceremony. Thomas was there, sitting in the front row with Dr. Hill and a couple of nurses who’d insisted on coming. They said their vows with a seriousness that made my chest ache. They didn’t promise a lifetime. They promised to love each other for as long as they were given, whether that was ten years or ten months. It felt more honest than anything I’d ever heard.

Chapter 5

Two years later, my mother is still alive. The cancer is still there, lurking in her body like a shadow that refuses to disappear, but it’s stable, controlled. She goes to Sloan Kettering once a month for treatment and spends the rest of her time living instead of just surviving. She and Adrien bought a house in Connecticut, a modest place by billionaire standards but enormous by ours. It sits on a stretch of coastline where the water meets the rocks in a constant, soothing rhythm. My mother always said she wanted to live near the ocean one day. Now, when I visit, I wake up to the sound of waves and gulls instead of sirens and traffic. I finished my degree at NYU and graduated last spring, walking across a stage in a rented cap and gown, my name announced to a room full of strangers and a small cluster of people who mattered—my mother in the front row, wearing a wig and a dress that matched the school colors, cheering louder than anyone; Adrien beside her, clapping until his hands were red; Thomas and Dr. Hill seated behind them, smiling like proud relatives. After the ceremony, we took photos in Washington Square Park. My mother held my diploma like it was made of gold. Adrien stood beside us, one arm around each of our shoulders. Someone walking by did a double take and whispered, “Is that…?” I didn’t care. For once, the world could watch. This was ours. I work now at a small publishing house in the city, reading manuscripts and writing rejection letters and occasionally falling in love with a book so hard I nag my boss until she buys it. I take the train up to Connecticut every other weekend. Sometimes more, if my mother’s having a rough week. We cook, we talk, we sit on the porch and watch the sky bleed colors into the water at sunset. Adrien grills fish like he’s learning a new programming language—carefully, methodically, determined to get it right. My mother teases him about his apron. He teases her about her growing collection of ridiculous sunhats. I sit back and let their voices wrap around me like a story I’m reading for the second time, catching all the details I missed before. One evening not long ago, we were on the back deck, drinking wine and watching the sun sink toward the horizon. The sky was streaked with orange and pink, the water reflecting it all like molten glass. My mother sat in a lounge chair, her legs tucked under a blanket even though the air was warm. Treatment days still wiped her out. Adrien sat beside her, their chairs pulled so close their arms touched. They were holding hands, fingers intertwined. Both of their left wrists were exposed, the tattoos clearly visible in the fading light. Two roses. Two sets of thorns twisted into infinity symbols. Faded, blurred at the edges, but still there. “Do you ever regret it?” I asked quietly. They both looked over at me. “Regret what?” my mother asked. “The tattoo,” I said. “Everything that came with it.” Adrien answered first. “It was the only proof I had that she was real,” he said, glancing at my mother. “That what we had wasn’t just something my brain made up in the lonely years after. Every time I thought, ‘Maybe I imagined it. Maybe I made her better in my memory than she was,’ I would look at my wrist and remember exactly how it felt to hold her hand in that tattoo parlor while the needle buzzed.” My mother smiled, the lines around her eyes deepening. “I kept mine for the same reason,” she said. “I thought about covering it, once or twice. I even made an appointment for removal. But when the day came, I couldn’t go through with it. It was all I had left of him. Of us.” “And now?” I asked. “Now it’s a reminder,” Adrien said, “that love doesn’t die just because you lose track of it. Even when you think it’s gone, even when twenty-five years pass, it’s still there. Waiting.” My mother looked at her wrist, then at his, then at me. “L’amore è bello ma fa male,” she said softly. “Ed è per sempre.” She’d told me those words when I was seven, a mysterious incantation I hadn’t understood. “Love is beautiful,” she translated, “but it hurts. And it’s forever.” “Forever,” Adrien echoed, lifting their joined hands to kiss the inside of her wrist, right over the faded rose. They didn’t get a fairy-tale ending. My mother is still sick. Some days she can’t get out of bed. Some days the scans show tiny changes that make my stomach clench with fear. We all know that one day, the treatments might stop working. One day, the cancer might win. But not today. Not this evening, with the sky on fire and the water soft and the air full of the smell of grilled fish and wine and salt. Today, she is here. Today, he is here. Today, I am here with them. When I look at their wrists, at the matching tattoos that started as a promise and became, somehow, a map back to each other, I don’t just see pain anymore. I see proof. Proof that love can be interrupted, postponed, buried under decades of silence and misunderstandings—and still survive. Proof that sometimes, against all logic, the people who are meant to be in your life find their way back to you. They sit there on the porch, fingers intertwined, talking in a mix of English and Italian, laughing at some memory I haven’t heard yet, and I realize something. The night I asked a billionaire about a tattoo in a crowded Manhattan restaurant, I thought I was breaking a rule. I didn’t know I was opening a door that had been stuck for twenty-five years. I didn’t know I was giving my mother back the love she’d lost, or giving myself the father I never knew I had. The past didn’t stay buried. It bloomed again, like a rose with thorns twisting into infinity. However long forever turns out to be for us, today, on this deck, in this moment, it feels real. And that’s enough.

News

‘RHOA’ Star Kandi Burruss Allegedly Caught Todd Tucker ‘Talking to Other Women’ Before Filing for Divorce: Report

The breakdown of Kandi Burruss and Todd Tucker’s 11-year marriage may not have been as sudden as fans thought. According…

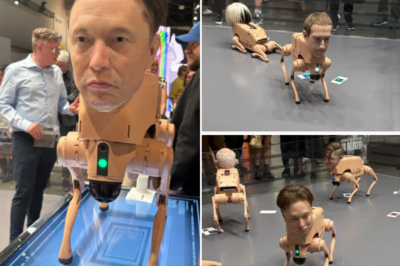

Beeple’s Wild Art Basel Spectacle: Musk, Bezos & Zuckerberg Robot Dogs Pooping NFTs Stop Miami in Its Tracks

Only at Art Basel Miami Beach could you turn a corner and find Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg…

Why Pregnant Alyssa Farah Griffin Has Been Absent From The View

Fans tuning in to The View this week may have noticed one seat consistently empty: Alyssa Farah Griffin’s. The 35-year-old…

Pramila Jayapal Says Mass Deportations of Somali Fraud Suspects Would “Hurt the U.S. Economy” — Sparks Outrage in Immigration Fight

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) is facing fierce political backlash after arguing on MS NOW Thursday that deporting Somali immigrants tied…

Inside Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s swanky Rhode Island wedding venue

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce are officially leaning into full-scale, coastal luxury for what is already shaping up to be…

Prince Harry Nearly Kisses Stephen Colbert in Hilarious ‘Late Show’ Christmas Skit

Prince Harry made an unexpected — and riotously funny — appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert Wednesday night,…

End of content

No more pages to load