If only five minutes could decide the fate of an empire, what would history look like?

At 10:25 in the morning on June 4th, 1942, flames swallowed three Japanese carriers. Black smoke boiled into a blue Pacific sky. Sailors leapt blind into burning water. Just days earlier, in Tokyo, men in crisp uniforms congratulated each other on the inevitability of victory, convinced that America was weak, slow, confused.

On a map, the two ideas never touched.

In reality, they collided in the waters off a tiny coral atoll called Midway—after a handful of codebreakers in a windowless room on Oahu solved a riddle nobody thought they could, and a few dozen American pilots flew themselves straight into legend.

Six months before that morning, Japan looked unstoppable.

From December 1941 to early summer 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army rolled across half the Pacific. Pearl Harbor. Malaya. Singapore. The Philippines. The Dutch East Indies. Burma. Guam. Wake. Hong Kong. Each new headline carried the same flavor: another defeat for the Allies, another island under the Rising Sun.

In Tokyo, newspapers spoke of destiny. Generals and admirals filled speeches with talk of divine favor and national spirit. Inside the Navy’s high command, an idea took root and wrapped itself around every conversation.

They called it “shōri-byō.”

Victory disease.

It sounded harmless. It wasn’t. It was the logic that says: we have won before, therefore we will win again. Momentum as a substitute for thinking.

Officers like Commander Minoru Genda, the brains behind the Pearl Harbor attack, convinced themselves that American pilots and sailors lacked the stomach for a long sea war. They were soft. They’d fold. Japan’s early string of victories seemed to prove them right. Anyone who questioned that narrative was brushed aside as timid or defeatist.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, saw further.

He’d studied at Harvard. He’d served as naval attaché in Washington. He had walked through American factories and shipyards and seen what the United States could build when it set itself to the task. Before the war, he had warned Japanese leaders: “For the first six months, I will run wild, and I will show you victory after victory. But if the war continues after that, I have no confidence of success.”

By May 1942, those six months were almost up.

Instead of pulling back, cooling the fever, and digging in, pressure in Tokyo rose. Operations officers like Matome Ugaki argued that they needed one more blow—one knockout strike so massive it would break American will and force Washington to the negotiating table.

They chose Midway as the fist.

On a globe, the choice made sense. Midway Atoll sat like a stepping stone between Japan and Hawaii. Take it, and you pushed your perimeter outward. You could threaten Pearl Harbor again. Force the Americans to spread what was left of their carriers thin.

The planners in the Combined Fleet building believed the Americans were down to two usable carriers. Yorktown, damaged at the Coral Sea, they assumed would be in repair yards for months. That left Enterprise and Hornet. Outnumbered two to four, with Japanese pilots riding on a string of unbroken victories.

On paper, it looked like a trap the United States had no answer for.

The problem was that halfway across the Pacific, in a low room stuffed with radio intercepts and cigarette smoke, a different set of men were quietly reading the script.

The place was called Station HYPO.

It was buried in the basement of the Fourteenth Naval District building at Pearl Harbor. There were no windows, no glory. Just racks of radios and codebooks and Commander Joseph Rochefort in a bathrobe and slippers, living on coffee and sarcasm.

Japanese fleet communications traveled encrypted in a codebook system the U.S. Navy designated JN-25. The Japanese believed it was secure. It wasn’t. Not completely. Day by day, word by word, HYPO’s cryptanalysts pieced together enough chunks of that code to get partial messages.

In May, those fragments started talking about an operation aimed at “AF.”

No one in Tokyo wrote “Midway” in the clear. They wrote “AF.” In Washington, some worried AF meant Hawaii itself. Maybe the West Coast.

Rochefort had a different hunch.

Midway had appeared before in Japanese traffic. And Midway was the logical step if you accepted Yamamoto’s idea of drawing out the American carriers for a decisive battle.

A hunch wasn’t enough. Rochefort needed proof strong enough to argue with admirals.

So he proposed a trick.

Midway’s garrison was ordered to send, in plain language, an uncoded radio message complaining about a broken desalination plant and a resulting shortage of drinking water.

A few days later, HYPO intercepted a Japanese encrypted message.

AF was reported to be “short of water.”

That was it. That was the line that snapped everything into focus. AF wasn’t Hawaii or Los Angeles.

AF was Midway.

Armed with that confirmation, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, made what might have been the most important decision of the naval war.

He would not wait at Pearl Harbor and react to the blow.

He would meet it.

He ordered Enterprise and Hornet to sea and rushed Yorktown into dry dock. Damage that should have taken months to repair was patched in roughly seventy-two hours. Men worked around the clock. Plates were welded. Holes covered. Systems jury-rigged to “good enough.”

She sailed with a full air group three days after limping into Pearl.

Nimitz sent all three carriers to a patch of ocean northeast of Midway. On the map, the square had no name.

Nimitz called it Point Luck.

There, the carriers would sit, invisible beyond the horizon, waiting.

Japan believed it was setting a trap at Midway.

In reality, the Americans had already read the bait tag.

For the first time since Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Pacific Fleet would not just react. It would ambush.

Before dawn on June 4th, aboard the Japanese flagship Akagi, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo gave the order.

Four carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu—turned into the wind. One hundred and eight aircraft clawed into the gray sky, the first wave: dive bombers, level bombers, fighters. Their targets: Midway’s airfields, fuel tanks, and defenses.

At around 6:30, they arrived over the atoll.

Japanese bombs walked across the runway, cratered parking areas, toppled hangars. Fuel drums exploded. The air shook.

But Midway did not die.

Marine pilots in outdated Brewster Buffaloes and F4F Wildcats threw themselves into the attack. Anti-aircraft guns thumped and banged, peppering the sky with black bursts. Radar-directed fire and sheer stubbornness kept the Japanese from obliterating the airfield. When Lieutenant Commander Tomonaga Joichi, the strike leader, took stock, he sent back a report that mattered more than any bomb.

“Midway’s air facilities are still operational. Further attacks are required.”

That nine-word assessment collided with Nagumo’s plan like a brick.

He had held half his strike aircraft back as a reserve, waiting with torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs attached—ready to pounce on any American ships that appeared. Now, to finish Midway before an invasion, he was faced with a sickening choice.

He could:

Keep his reserve armed against ships and risk leaving Midway’s airfield alive.

Or strip off the naval ordnance, rearm them with land bombs, and hit the island again—but risk being caught with hangars crammed full of fueled planes, bombs on dollies, hoses everywhere, and decks jammed with aircraft trying to land.

He chose the second option.

Below decks, organized precision turned to organized chaos. Crews hauled torpedoes off planes and dragged them back into magazines. Armor-piercing bombs came off racks. General-purpose bombs for land targets had to be winched up. Fuel lines ran in all directions. Aircraft handlers tried to move returning planes and re-arming craft around the same cramped spaces.

Japanese carrier doctrine liked things neat: one operation at a time. Right now, Nagumo’s four decks were trying to do three.

Then another problem surfaced.

A destroyer-launched scout plane, delayed on takeoff earlier that morning, finally radioed in: it had sighted American ships. Including a carrier.

The nightmare scenario. The enemy carriers were close, not safely locked up in Pearl.

Nagumo’s staff tried to pivot again. Torpedoes back up. Land bombs down. The carriers twisted in their own procedures.

Meanwhile, in the high, cold sky above, Americans were coming.

At 9:20, the first American torpedo squadron found the Japanese.

They came not from Point Luck, but from Midway itself: obsolete TBD Devastators and some jury-rigged B-26s carrying torpedoes—not ideal weapons, flown by men who knew the odds and went anyway.

The Devastators were slow. Underarmed. Under-armored. Many had malfunctioning torpedoes. Lieutenant Commander John Waldron of Torpedo Squadron Eight on Hornet had told his men before they ever launched: “If only one plane makes it through, it must go in and get a hit.”

Over the next hour and a half, that spirit was played out three times.

Torpedo Eight from Hornet. Torpedo Six from Enterprise. Torpedo Three from Yorktown.

They attacked alone, in sequence, not in the massed, coordinated package doctrine would have wanted. Communications issues and misaligned back-of-the-envelope navigation had scattered them.

They came in low, slow, and straight, because you had to fly that way to drop torpedoes in the 1940s.

The Zeroes swooped out of the sun and murdered them.

Devastators caught fire and folded into the sea. Men burned or bailed out. Torpedoes wobbled, ran erratically, or were easily avoided by Japanese captains throwing their ships into tight turns.

Torpedo Eight lost all fifteen planes. Only Ensign George Gay survived, floating in the debris, watching the battle from sea level.

From the Japanese bridges, it looked like butchery. Clumsy Americans. Brilliant defensive flying. A one-sided slaughter.

Not a single torpedo hit home.

From a tactical perspective, the runs were a failure.

From an operational one, they were the key to everything.

They had dragged the Japanese CAP—Combat Air Patrol—down to the deck. Zero pilots burned fuel, dove, climbed, and chased targets at low altitude. The torpedo runs had also forced the carriers into violent evasive maneuvers, delaying their ability to cycle aircraft.

High above, out of sight, dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown were searching.

Commander Wade McClusky, leading Enterprise’s SBD Dauntless squadrons, had been given a general location—not a precise one. His fuel was running down. He found nothing where his first orders had sent him. He could have turned back.

Then he saw a lone Japanese destroyer—Arashi—running at high speed, nose pointed in a direction that didn’t match basic patrol patterns.

Arashi had just finished trying to depth-charge an American submarine that had been trailing the Japanese force. Now it was racing to rejoin the main body.

McClusky trusted that wake.

He turned his squadrons to follow it.

Minutes later, the haze parted.

Four Japanese carriers lay below like islands of gray in a blue field.

At 10:20, McClusky gave the signal.

Dauntless pilots rolled their planes over and pointed them straight down.

The Japanese fighters were low, still chasing ghosts from the torpedo attacks. The carriers, mid-conversion and mid-recovery, had decks cluttered with planes and explosives. Below, ammunition and fuel were stacked in half-completed patterns.

Kaga took the first hammer blows.

Dauntlesses from Enterprise’s Scouting Squadron Six and Bombing Squadron Six made a fatal mistake that turned into a miracle—they all dove on the same target. One bomb after another smashed into Kaga’s flight deck, punching holes that ripped into hangars full of fueled and armed aircraft. Fire raced through her insides.

Akagi was hit next, not by many bombs, but by one placed with terrible perfection. It punched through the deck near the center and ignited bombs and fuel below. Secondary explosions turned the ship into a furnace.

Soryu, to the east, was struck by Dauntlesses from Yorktown. Bombs dug into her forward sections and hangars. Flame and smoke poured out. Planes and men died in moments.

In roughly five minutes, three of Japan’s first-line carriers—the same ships that had launched planes against Pearl Harbor just six months before—were mortally wounded.

On their bridges, calm staff officers who had once watched success unfold like clockwork now stared at walls of flame and lists of dead.

Only Hiryu remained.

Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, commanding on Hiryu, refused to fold. Where some might have cut losses and run, he chose to fight with what he had.

He launched a counter-attack.

Hiryu’s dive bombers found Yorktown around midday. They came screaming out of cloud, and their bombs struck true. Fires erupted. Power flickered. For a while, Yorktown looked like a lost ship.

But American damage control—a skillset drilled hard after Pearl Harbor—showed its value. Fires were contained. Power was partly restored. Within an hour, Yorktown was making turns again.

Hiryu launched torpedo planes next.

They found Yorktown as well.

This time, the torpedoes hit. Two slammed into the carrier’s side, snapping power again, flooding compartments, and leaving the ship dead in the water. By late afternoon, the order came to abandon ship.

Yorktown had survived Coral Sea. She would not survive Midway.

But her sacrifice bought time and space.

Scouts had already fixed Hiryu’s location.

Dauntlesses from Enterprise and the patched-up Yorktown group turned toward her. They arrived late in the day, dropping through cloud to find the last Japanese carrier still making wind for flight operations.

They hit her.

Explosions ripped through Hiryu just as they had through her sisters. Fires took hold. Yamaguchi refused to leave. He chose to go down with the ship, taking his place beside the captain on the burning bridge.

By nightfall, she was finished.

Japan had sailed toward Midway with four fleet carriers.

By the next morning, all four were headed for the bottom or already there.

The strategic math was simple and devastating.

In one day, the Imperial Japanese Navy lost Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu. Alongside them went more than three hundred aircraft and many of the best trained naval aviators Japan had.

Those pilots couldn’t be replaced quickly. The Japanese training pipeline was long and harsh. It produced elite fliers—but in small numbers. Losing dozens of veterans in a single afternoon was like tearing out the nervous system of the fleet.

American losses at Midway were sharp, but America had depth.

Yorktown died. Dozens of aircraft were shot down. Pilots were killed or captured. Torpedo squadrons were gutted.

But Enterprise and Hornet sailed home. American shipyards in places like Newport News, Brooklyn, and San Francisco were already pushing new carriers down their ways—Essex-class decks that would soon join the fight. American training squadrons were turning farmers’ sons and college kids into pilots by the hundreds every month.

Japan could still fight. It would fight ferociously for three more years.

But after Midway, it would never again be able to seize the initiative with its carrier force.

After Midway, Yamamoto’s vision of luring the Americans into a single decisive showdown flipped. Japan’s carriers were now the ones avoiding pitched fleet actions. America started choosing when and where to fight.

Two months later, Marines splashed ashore on a little island called Guadalcanal.

There, on land and sea and in the air, the United States proved it had the endurance to turn Midway’s five minutes into a campaign of years. And in the Marianas in 1944, new American carriers, bristling with fighters and flown by pilots who had trained in the wake of these earlier lessons, would shoot down so many inexperienced Japanese aviators in a single day that someone dubbed it the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

Midway didn’t end the war.

It ended Japan’s hope that the war could end on its terms.

It also wrote a few truths in saltwater and flame.

That arrogance can blind even the most powerful.

That in carrier warfare, time—minutes, not months—is lethal currency.

And that you can rebuild ships and airplanes in a year or two, but you cannot replace an entire generation of elite aviators in time to save an empire.

The U.S. victory at Midway didn’t come from luck alone. It came from a codebreaker who hid behind a bathrobe and insisted that “AF” meant Midway, from admirals willing to act on that intelligence, from torpedo pilots who flew into walls of fire knowing they probably wouldn’t come back, and from dive-bomber pilots who rolled over into the sky and pointed their noses at smoke and death because that was the way out.

Midway was steel and aviation gas and bombs.

But beneath all that, it was human decisions—made in basements and on bridges—and human courage, poured into a five-minute window that changed the shape of the Pacific.

The ocean looks the same now as it did that morning.

Calm from a distance, empty to the eye.

But if you listen carefully to the history written on its surface, Midway whispers the same quiet warning:

Don’t mistake momentum for destiny.

Don’t ignore the uncomfortable intelligence because it spoils the story you prefer.

And never forget that sometimes, in war as in life, the handful of minutes no one planned carefully for are the ones that decide everything.

News

At My Sister’s Wedding, I Was Seated In The Hallway, So I Left. What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

Chapter 1 – The Golden Child and the Ghost Guess you don’t count. That’s what my sister said when the…

My Sister-in-Law Announced She Was Taking My Position at Work—She Didn’t Know I Owned the Company…

Chapter 1 – The Announcement The private dining room at Chez Laurent still hummed with that lazy, satisfied buzz that…

Sister Deleted My Medical School Application — The Dean Was Watching Her Screen…

Chapter 1 – The Withdrawal The champagne bottle popped in the next room, followed by a chorus of laughter and…

My Mother-in-Law Sold My Family Home Without Asking. The Next Day, She Was Crying…

Chapter 1 – A Life That Worked My name is Emily, I’m forty-four, and most evenings my face is the…

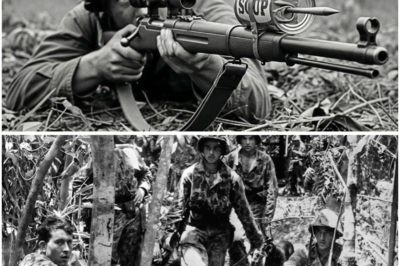

How a U.S. Sniper’s “Soup Can Trick” Took Down 112 Japanese in 5 Days

November 11th, 1943. 0530 hours. Bougainville Island, Solomon Islands. The mist hung low and heavy over the forward perimeter of…

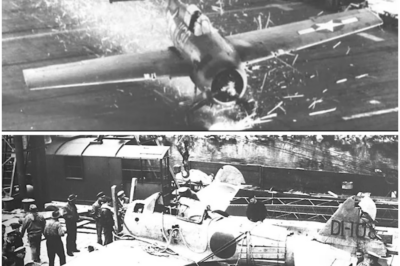

The Japanese Pilot Who Accidentally Landed on a U.S. Aircraft Carrier

April 18th, 1945. Philippine Sea, two hundred and forty miles east of Okinawa. A lone Zero limped through the low…

End of content

No more pages to load