The phone wouldn’t stop ringing. It lit up on the coffee table over and over, buzzing against the wood, Garrett’s name glowing on the screen like a warning flare. My hand trembled when I finally reached for it, the purple bruise around my wrist still tender, the ache in my ribs a dull reminder every time I exhaled too deeply. It had been two days since Christmas Eve, but my body hadn’t gotten the memo. Every breath still felt like it happened inside a bruise.

Outside the living room window, the December light was sharp and clean. Frost covered the lawn in a thin white sheet, glittering where the winter sun caught it. A crow hopped around my frozen birdbath, pecking uselessly at the ice, cocking its head like it couldn’t understand why things that used to work suddenly didn’t. I knew the feeling.

The phone buzzed for the third time. My lawyer had told me not to answer, that nothing good was going to come from hearing his voice before the paperwork was done. The restraining order sat on the coffee table beside me, stapled neatly, my signature line blank and waiting. But habit is a stubborn thing, and a mother’s reflex is worse. Before my brain could catch up, my thumb slid across the glass.

“Mom.”

His voice cracked right through the speaker. It wasn’t the confident, dismissive tone I’d heard two nights ago in my kitchen. This voice shook, thin and young, like he was calling from a hospital bed instead of a three-car driveway and a kitchen full of stainless steel.

“Mom, did you… did you pay the mortgage this month?”

The question sat between us like smoke. I shifted in Bernard’s old recliner, and pain shot through my ribs. The emergency room doctor had called it “severe bruising, no fracture, deep tissue damage.” I called it a reminder. I adjusted the ice pack on my hip and watched the crow give up on the birdbath and fly away.

“Why would you think I paid your mortgage?” I kept my voice steady, the way I used to when he was seven and insisted he “found” the neighbor boy’s baseball cards.

He exhaled hard, the sound turning staticky through the phone.

“Because the payment didn’t go through. The bank tried to pull it and it bounced. Our account shows insufficient funds. And I know you usually… you’ve helped us before when we were short.”

Usually. That little word landed heavier than he probably meant it to. Like “usually” it was my job to patch the holes in his life.

“I’m confused, Garrett.” I shifted in the chair, the leather creaking under me. “Two nights ago, you told me I had more money than I’d ever need. You told me I was going to die alone in this house anyway, so what I did with my money was none of your business, remember?”

Silence. I could picture him in his kitchen, the one with the granite countertops I’d helped them pick out because the first set they wanted was too expensive. I’d written a check to cover the upgrade; they’d thanked me with a text. I imagined him standing there now, phone pressed to his ear, his face cycling through panic and realization. It was the same look he’d had when he was twelve and got caught slipping a pack of baseball cards into his jacket at Target.

“Mom, listen,” he started.

“No.” My voice stayed soft, but there was steel underneath now, a steel that had never been there before. “You listen. Your wife stole thirty thousand dollars from me. You knew about it. You gave her my card and my PIN. And when I confronted you both about it, you shoved me to the ground in my own kitchen and left me there bleeding with a concussion. The police have photos. The hospital has records. My lawyer has documentation of every single withdrawal she made.”

I paused. Let the weight of those words settle where they belonged instead of in my chest.

“So no, Garrett. I did not pay your mortgage.”

“Mom, please.” His voice cracked again. “They’re going to foreclose. We’ll lose the house. Everything. Just this once. Just help us this once.”

A laugh came out of me. It didn’t sound like me. It was short and sharp and humorless.

“Just this once?” I shook my head, even though he couldn’t see it. “I gave you twenty thousand for your down payment. I’ve covered your car payments, your credit card bills, your ‘emergencies’ for years. I’ve watched your dogs whenever you wanted to travel, cooked for you almost every Saturday, and let you talk to me like I’m an obligation instead of a person. I gave and gave, Garrett. You repaid me by stealing from me and putting your hands on me.”

“I’m sorry. God, Mom, I’m so sorry.”

“Are you sorry you did it,” I asked, “or sorry you got caught?”

There was no answer. Just his breath on the line, ragged and panicked. Outside, another crow had landed, two of them now circling my frozen lawn looking for food that wasn’t there.

“Let me tell you what happened two nights ago,” I said. “Then you’ll understand why I won’t help you. Why I can’t.”

Chapter 2

Three months earlier, on a Friday in September, I’d been a different woman.

Back then, I still thought of myself as what I’d been my whole life: a nice woman. A good mother. Cordelia Whitmore: retired elementary school teacher, widow, book club regular, reliable Saturday dinner guest at my son’s house, “Grandma” to two spoiled golden retrievers. I’d lived seventy-two years believing that if you showed up, gave generously, and didn’t make waves, life would, if not reward you, at least leave you in peace.

Friday was book club day. The women—Margaret on Maple Street, Ruth from church, Sandra who always forgot her glasses—would gather in Margaret’s living room at two o’clock sharp. We read historical fiction mostly, sometimes mysteries. We’d drink tea, eat lemon bars, talk about characters as if they were neighbors. It was a comfortable routine, something solid to grab onto after Bernard died.

That Friday, Margaret called at one thirty sounding breathless. Her daughter had gone into labor three weeks early. No book club, she said. Baby’s more important than fiction. We laughed, agreed, told her to send pictures.

I’d already showered. My good cardigan was laid out. The lemon bars were in the oven, almost done. There didn’t seem much point in going back to my empty house just yet. So I put the lemon bars in a tin, grabbed my purse, and drove without really having a destination in mind.

It was one of those early fall days Ohio does better than anywhere—air cool enough for a sweater but sun warm on your face. The trees on Pinewood Avenue were just starting to turn, a few yellow leaves here and there, mostly still green. I drove past the new coffee shop, past the park where I used to take Garrett to push him on the swing, past the bank Bernard and I had used for more than thirty years.

The ATM there was convenient. I always liked to keep a little cash in my wallet. You never know when you’ll need it. I pulled into the lot, found a spot, and that’s when I saw it: the red coat.

It was that obvious. Bright crimson wool, cinched at the waist, hitting just at the knee. I knew that coat the way you know your own handwriting. I’d bought it for Vanessa last Christmas. She’d pointed it out in a catalog once, sighed, said, “It’s gorgeous, but too much. We can’t afford things like that.” I’d remembered. Saved up. Went to the mall alone and bought it, my hands shaking while I slid my card through the machine. Eight hundred dollars plus tax. I’d thought, we don’t spend this kind of money on things like that either—but my daughter-in-law will look beautiful and maybe, just maybe, she’ll finally see me.

She’d opened it Christmas morning, squealed, held it up to her body, twirled. It was the first time she’d ever hugged me.

Now she was standing in front of the ATM, wearing that coat, her hair twisted up in a perfect knot, tapping something into the machine. Our Mercedes—that’s what I still thought of it as, because I certainly felt the payments in my bones—sat two spots over, exhaust puffing in the crisp air.

I watched as she took a stack of cash from the machine. Not a few twenties. A stack. She counted it quickly, glanced around. I ducked down, ridiculous reflex—like I was the one doing something wrong—then peeked back up just in time to see her shove the money into her purse and walk back to the car.

She drove away. I sat there with the engine idling, staring at the empty spot, the ATM screen now back on its default advertisement: We’re here for all your financial needs.

It could have been a coincidence. Maybe she’d opened an account at our bank. Maybe Garrett had sent her. Maybe there was a surprise in the works. My stomach told me something else.

Inside, the bank smelled like it always did: carpet cleaner, paper, and that vaguely cold scent office buildings have. Susan Williams, the personal banker who’d helped me open my accounts after Bernard died, smiled as soon as she saw me.

“Cordelia,” she said. “What brings you in today?”

“I need to look at my checking account,” I said. “The one I opened with Bernard’s insurance payout, after he passed.”

Her smile dimmed but stayed polite. “Of course. Any specific concerns?”

“Just feeling like I should check it.”

She pulled my file, clicked a few keys. The glow from her monitor made her face look younger, sharper.

“Do you want to see it on screen or a printout?” she asked.

“Both,” I said. My voice sounded calm. I gripped my purse so tightly my knuckles ached.

The numbers appeared. There it was. Every withdrawal, every deposit, neat little lines on a neat little screen. $3,000 withdrawn. Friday. 2:15 p.m. Another $3,000 the Friday before. And the Friday before that. Eight months of Fridays. Every one at 2:15 p.m. Every one for the same amount.

“Can you show me the original signatures card?” I asked quietly.

Susan’s eyes flicked to mine, something like concern in them now instead of cashier friendliness. She pulled it up. There was my signature. Just mine. No joint owner. No co-signer. No power of attorney.

“You didn’t authorize someone else?” she asked.

“I gave my son a card,” I said. “For emergencies. For his car, in case it broke down. For real emergencies.”

She hesitated.

“If you think these might be fraudulent, we can look at security footage,” she said. “Are you sure you want to do that?”

“I’ve been sure about a lot of things that turned out to be wrong,” I replied. “I’m trying something new.”

They took me into a side office, a little room with a round table and a monitor on the wall. A young man in a tie fiddled with a USB drive. The footage appeared. Grainy, black-and-white but clear enough.

Friday, September 13, 2:17 p.m., timestamped in the corner. The ATM camera’s angle caught the side of the person’s face. Red coat. Dark hair in a knot. Vanessa’s face, concentration drawn into a little frown while she tapped the keypad. Card in. Card out. Cash in hand. She counted it with quick, practiced fingers, slipped it into her bag, and left.

Friday, September 6. Same coat. Same woman. Same actions.

August 30. August 23. Eight months of Fridays played out in jerky time. Eight months of my daughter-in-law taking my money like it was her allowance.

I watched the screen until my eyes blurred, then requested a copy of the footage. They said I’d need to speak to the police. I nodded. Took the printout of my statements, the footage on a thumb drive, walked back to my car, and sat there with my hands on the steering wheel for a long time.

At home, the lemon bars still sat on the counter untouched. I moved like a sleepwalker, straight to the living room, straight to Bernard’s recliner. Sat down, set the papers in my lap, and stared at that water stain on the ceiling.

Bernard had always said he’d fix it when he got around to it. Then his heart gave out in that very chair, coffee cup dropping to the rug, his eyes still open and staring at that unfixed stain. I’d refused to paint over it. It was a reminder that time runs out whether you’re ready or not.

The lemon bars went stale in their tin. I didn’t eat dinner. I didn’t call anyone. I didn’t cry either. I just sat and watched the way the late afternoon light shifted across my living room floor and realized slowly, like someone waking up from anesthesia, that the life I thought I had was an illusion I’d been maintaining by sheer force of habit.

The next day, I traced every withdrawal back, tallied the total: $30,000. That was my safety. My surgery money. My “if I fall” money. Gone. Dripped out of an ATM on Fridays while I chatted about fictional people’s troubles and thought my life was manageable.

Christmas was a few months away. I decided to wait. To plan. To give them one chance, face to face, to explain, to apologize, to choose a different path. Foolish, maybe. But I needed them to show me who they were with the truth on the table, not just the bank statements.

Chapter 3 – Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve dawned crisp and white, frost painting lace on the corners of my windows. I woke up early, like I always do on holidays, even though there was no child in the house to wake for Santa anymore. Old habits don’t die; they just get quieter.

I showered, pulled on the red sweater Garrett had given me years ago, the one with the little snowflake pattern around the collar. It didn’t fit as well as it used to. Age rearranges more than your bones. But it was warm, and it reminded me of a time when my son’s gifts came from love and not obligation.

The turkey breast went in the oven at ten. I peeled potatoes, snapped green beans, rolled out sugar cookie dough and pressed it into stars and trees. The kitchen smelled like every Christmas I’d ever hosted: roasting meat, butter, sugar, vanilla, coffee.

The bank statements sat folded in the pocket of my apron. I’d touched them so often the edges were starting to go soft. I’d rehearsed what I was going to say a hundred times in my head while kneading dough and setting the table. This is what you took. This is how you took it. This is why it was wrong.

By four, the table was set for three. My good china, the wedding set Bernard’s mother had given us in ’68, white with little blue flowers around the rim. Cloth napkins. The candles I only light for holidays. I’d even put Vanessa’s favorite fancy napkin ring on her setting, the one shaped like a silver bow.

They were supposed to arrive at six. The doorbell rang at 4:47.

Through the frosted glass, I saw the outline of the Mercedes in my driveway, exhaust steaming in the cold air. I wiped my hands on my apron, checked my hair in the hallway mirror, and pasted on the smile I’d worn for years, the one that said, Everything’s fine.

When I opened the door, Garrett swept in like he owned the place, kissed my cheek without looking at me, already shrugging out of his coat.

“We’re early,” he said. “Vanessa wanted to help with dinner.”

Vanessa glided past him in heels that clicked sharply against my hardwood floors. The red coat framed her like a picture. She carried a store-bought pie in a plastic container.

“Merry Christmas, Cordelia,” she said.

Not “Mom.” Not even “Mother.” Just my first name, clipped cleanly like we were colleagues at a staff meeting.

I shut the door behind them, feeling the cold linger on my back for a split second too long.

In the kitchen, she opened my refrigerator without asking, pulled out the bottle of Chardonnay I’d been saving.

“Oh good,” she said. “This will go perfectly with the turkey.”

She poured two glasses, one for herself, one for Garrett. Didn’t offer me one.

I set the mashed potatoes on the stove to keep warm, turned down the oven. My heart was pounding so hard I could feel it in my teeth.

“Actually,” I said, my voice cutting through her chatter, “I need to talk to you both first.”

Vanessa sat at the table, crossed her legs, took a sip of wine. She waved her free hand in a “get on with it” gesture.

“What’s up?” Garrett asked, pulling at his tie like it suddenly bothered him.

I reached into my apron pocket and pulled out the folded paper. It felt heavier than it should for its weight.

“This is my bank statement,” I said. “From the account I opened with your father’s life insurance after he passed. The one still in his name and mine. The one nobody else is authorized to use.”

Garrett frowned.

“Okay?” he said cautiously.

“There have been withdrawals from that account,” I continued. “Three thousand dollars at a time. Every Friday at 2:15 in the afternoon for the past eight months. Cash taken from the Pinewood and Fifth ATM.”

I laid the statement flat on the table between us. The numbers stared up, indifferent. Facts never care who they hurt.

“I didn’t make those withdrawals,” I said. “So I went to the bank. They pulled the security footage.”

Vanessa’s eyes narrowed just a hair, but her smile didn’t move.

“Cordelia,” she said in a tone that suggested I was overreacting, “what are you implying?”

“I am asking,” I said, “did you take money from my account?”

She laughed. It was light and airy on the surface, but there was something hard underneath.

“Excuse me?” she said again. “Are you accusing me of… what? Robbing you?”

“Yes,” I said. “I saw the footage. Red coat. Our Mercedes in the background. You, every Friday, taking my money.”

Garrett stared at the paper, then at me.

“Mom,” he said. “You must be confused. You probably authorized this and forgot. You’ve been under a lot of stress.”

“I’ve been under stress before,” I said evenly. “When your father died. When I had pneumonia. When you totaled your first car. I still knew what I did with my money.”

“Maybe you should get checked out,” Vanessa said, her voice going cool. “Memory problems are common at your age. My grandmother was convinced her neighbor stole her garden hose for six months before—”

“Don’t you dare,” I snapped. The sharpness in my own voice surprised me. “Don’t you dare stand in my kitchen, wearing my coat, drinking my wine, and suggest I’m crazy because it’s convenient.”

Vanessa’s mask slipped. Just a flash, but enough.

“Fine,” she said. “Garrett told me about the card. He said you wouldn’t miss it. We needed the money. You’ve got plenty.”

My breath left my lungs like someone had opened a door in a blizzard.

“You knew?” I turned to my son. “You gave her my card? My PIN?”

He shifted, eyes sliding away.

“I told her to take out a little,” he muttered. “Three thousand once. For the house payment. We were behind. She must’ve… kept doing it.”

“You ‘told her’ to take out three thousand from my emergency fund,” I said. “And then you never checked to see if she paid it back?”

“We were going to,” he said. “Things just… got tight. You have more money than you need. What are you even saving it for? You don’t travel. You don’t spend it. You sit here alone in this house. We’re building a life. We’re a family.”

The word “family” burned.

“That money,” I said, enunciating each word with care, “was for my hip surgery. The one my doctor says I need before the end of next year. Insurance covers most of it, but not all. That account was my safety. You knew that. I told you.”

“You’ll be fine,” Vanessa cut in. “You’re tough, Cordelia. You don’t need a fancy surgery. You need to stop hoarding and start helping.”

“Helping?” My hands shook now. Not with fear. Not anymore. With fury.

“I have watched your dogs every time you asked. I have cooked for you every Saturday. I paid your down payment. I bought you that coat.” I pointed at the red wool on her shoulders. “I helped with your car, your credit card bills. How much ‘helping’ is enough, Vanessa?”

“You act like you’re some saint,” she scoffed. “You just want to control us with your money. You want us to feel guilty every time we accept it.”

“I wanted you to feel grateful,” I said. “Not entitled.”

Garrett’s jaw clenched.

“You’re overreacting,” he said. “We had no choice. We were going to lose the house. We could’ve been homeless. You’d rather keep your precious surgery money than help your only son?”

I stared at him. Really looked. Saw Bernard’s eyes in his. Bernard’s stubbornness. Bernard’s ability to twist any argument into one where he was the victim even when he was the one swinging.

“I would rather walk with a cane than keep funding your bad decisions,” I said.

He took a step closer. His hands came up, palms out like he was pleading, but there was rage in his face.

“You’re going to regret this,” he said. “We won’t come around anymore. We won’t bring the dogs. We won’t spend holidays with you. You’ll die in this house alone with your stupid money.”

Something snapped.

“Get out,” I said.

“You are making—”

“Get out of my house,” I repeated, voice cold now. “Both of you. Right now.”

Vanessa stood, her chair scraping loud against the floor.

“Gladly,” she said. “I’m tired of pretending. Garrett, let’s go. Let her rot with her old movies and her burned food.”

I grabbed the wineglass she’d been drinking from. My wine. My glass. My hand acted before my brain. I threw it. Not at them, never at them. At the cabinet above the counter.

The glass shattered with a crack that echoed through the house. Chardonnay sprayed across my white curtains, across the cookies I’d decorated, across the little ceramic Santa Abby had painted in third grade. Shards rained down like glitter.

“Jesus, Mom!” Garrett shouted.

He lunged. In my mind, he was leaving. Stepping around me to the door. In reality, he grabbed my shoulders and shoved.

I wasn’t prepared for the force. I’d held him as a baby, as a toddler, as a teenager slamming doors. I knew the strength in those arms, but I’d never been on the receiving end of it.

My hip slammed into the corner of the counter. White pain exploded from bone to muscle. My heel caught on the rug Bernard and I had bought on vacation. I fell backwards. The floor rushed up fast.

The back of my head hit hardwood with a crack that felt like lightning. The world went white, then black, then strange, swimmy gray.

Somewhere through the ringing in my ears, I heard Vanessa’s voice.

“Garrett, what did you do?”

“She’s fine,” he said. “She slipped.”

“You pushed her!”

“She threw a glass at us! What was I supposed to do?”

Their footsteps retreated toward the front door. The last thing I heard before it slammed was Vanessa’s voice, cold and flat.

“We’re done with you, Cordelia. Don’t you dare call us.”

Silent night drifted from the radio as I lay there on the floor, blood from my temple trickling warm into my hair, Christmas lights blinking cheerfully in the next room.

Chapter 4 – Consequences

Two days after Christmas, the bruises were a storm of colors blooming across my body. My hip was yellowing at the edges. My wrist was a deep purple where I must’ve instinctively thrown my arm out to break my fall. The gash on my temple had gotten three stitches and a stern talk from the ER doctor about head injuries and elderly patients.

“Elderly,” I’d repeated with a bitter little smile. “First time anyone’s called me that to my face.”

“You’re lucky,” he said. “This could’ve been much worse.”

“Lucky,” I’d echoed. “That’s one word for it.”

Officer Martinez had taken my statement in the hospital. He’d sat at my bedside, notebook open, pen ready. He’d listened carefully, asked clarifying questions, never once suggested I was overreacting.

“Family violence is still violence,” he’d said when I stumbled over the word “assault.” “It doesn’t get a different name because you share genes.”

They’d taken pictures. So many pictures. My house had felt like a crime scene when I went home. Yellow tags on the floor where the glass had fallen, a dusting of powder on the counter to show the length of my skid, dark circles where blood had been cleaned.

The restraining order paperwork came the next day delivered by a kind-eyed woman named Detective Walsh. She’d sat at my kitchen table, explained the process, slid the forms toward me.

“You don’t have to decide today,” she’d said. “This is your call. But based on what we’ve seen, you have grounds.”

“I’ve been his mother for forty-six years,” I’d said. “I never imagined…”

“People do unimaginable things when money and entitlement get mixed together,” she replied.

The phone calls started as soon as I was home. First Vanessa, furious voicemail accusing me of ruining their lives. Then Garrett, alternating between angry and pleading. I let them ring. My hand hovered near the phone each time, trembling. I told myself the same thing I used to tell my students when they wanted to snatch the answer before they had all the facts.

“Wait.”

On the third morning, the phone buzzed again. Garrett’s name lit up. I almost hit decline. Almost. Instead, I answered. Maybe I needed to hear exactly who he’d become one last time.

We had our conversation. By the time it ended, the person who hung up the phone was not the same woman who’d answered it.

I signed the restraining orders that afternoon. My hand didn’t shake. Fiona came by to pick them up herself.

“I’ve rearranged your accounts,” she said. “Everything is moved. Your son and Vanessa are off every one of them. No more debits. No more access. We’ll file the civil suit next week.”

“The civil suit?” I asked. I hadn’t gotten that far in my thinking.

“To recover the funds plus interest and your legal fees,” she replied. “You lost $30,000. We’re going to get it back or watch them drown trying.”

“And the criminal charges?”

“That’s up to the state now,” she said. “The DA’s office is interested. They don’t like elder abuse cases. They like them even less when you have financial fraud wrapped around them like a bow.”

We sat in the living room, two women on a couch in a house that suddenly felt like mine again for the first time in years.

“Do you feel guilty?” she asked me out of nowhere.

“For pressing charges?” I shook my head. “No. I feel stupid. For waiting so long to see them clearly. For raising a son who thought it was okay. For how much of my life I wasted being afraid of upsetting people.”

“Stupid isn’t the word I’d use,” Fiona said. “Trusting, maybe. Generous. But not stupid. Stupid is what they did. Stupid is burning bridges to the one person who’s ever bailed you out and then asking that person to rebuild the bridge.”

We both glanced at the silent phone on the table, as if it might ring on cue. It didn’t. For once, it behaved.

The months that followed were slow and fast all at once. Trauma has a strange way of bending time. Some days, it felt like Christmas Eve had been ten minutes ago. Other days, it felt like a bad movie I’d seen last decade.

PT was hard. They had me walking with a cane around the therapy room, balancing on foam blocks, doing exercises with big elastic bands that made my arms shake. My body complained, but my mind was sharp. Sharper than it had been in years. It’s amazing what removing two leeches from your life can do for clarity.

I filled my days with things that had nothing to do with Garrett or Vanessa. I went back to book club. I volunteered more hours at the library. I started leaving birdseed out for the crows. They came every morning at eight thirty and strutted around like they owned the place. We understood each other.

In March, the foreclosure notice hit their mailbox. I know because the real estate agent told me when he called to see if I wanted to “help them save the house.” Maybe the old version of me would’ve crumbled. Would’ve called the bank, written another check, convinced herself they’d learned their lesson this time.

“I’m not interested,” I said.

“What if they end up homeless?” he asked.

“They’ll end up wherever their decisions lead them,” I replied. “Same as the rest of us.”

April brought my hip surgery. Patricia came back into my life then, this time as a friend instead of a nurse on shift. She sat with me the morning of the operation, knitting quietly in the corner of the pre-op room while they hooked me up to IVs.

“You nervous?” she asked.

“Less about this than I was about signing those papers,” I said.

She smiled. “That’s a good sign.”

Waking up after surgery was like surfacing from deep water. The pain was there, sharp but controlled. I remember the first thought that drifted through my foggy mind.

“I can’t wait to walk in my garden.”

That was new. For years, my first waking thought had been, “What does Garrett need from me today?” or “What did I forget to do for them?” That loop was gone. I’d replaced it with something that was actually mine.

The criminal trial started in September, exactly nine months after Christmas. Garrett looked older when he stood at the defense table. Maybe it was the stress. Maybe it was the county jail diet. Vanessa sat behind him on the first day, then stopped coming. Word around town said their marriage was as over as our relationship.

I took the stand on day two. Swore an oath. Told the truth. Not with drama, not with tears, though my eyes burned. I walked the jury through my routine, the money, the bank, the footage, the confrontation, the fall. The prosecutor played the video of Vanessa at the ATM, the red coat bright even in grainy black-and-white.

Garrett’s lawyer tried to twist it into confusion, misunderstanding, an “accident.” He suggested I had balance issues, that perhaps I’d slipped on my own. That maybe I’d authorized Vanessa to use the card and forgotten.

“Do I look confused to you?” I asked him.

I didn’t look at Garrett while I testified. I didn’t look at him when they read the verdict either: guilty on all counts. I only looked at the judge when she said the words I’d been waiting to hear.

“Eighteen months incarceration. Full restitution of thirty thousand dollars plus interest. No contact with the victim without court approval.”

Victim. That word still felt strange, like a coat that didn’t quite fit. I didn’t feel like one. I didn’t want to be one. But the law needed a label for what happened, and that one worked on paper.

Outside the courthouse, a young reporter with a microphone asked me the question people always ask in situations like this.

“How do you feel?”

“Free,” I said.

It was the only honest answer.

Chapter 5 – Choosing Myself

Six months has a way of changing a person more than six years sometimes. By the time winter rolled back around, I hardly recognized the woman who’d lain on that kitchen floor.

My garden was thriving. The hip surgery had worked. I could bend again, kneel even, if I did it carefully. I planted tomatoes and basil, marigolds to keep the pests away. Not because I needed the vegetables, but because watching something grow that you nurtured yourself is a kind of healing money can’t buy.

Patricia and I had coffee every other Thursday at the little café on Pinewood. We’d sit near the window, watch people walk by bundled in coats, and talk about books, about recipes, about our neighbors’ ridiculous lawn decorations. Sometimes she’d ask about Garrett, about whether I’d heard from him.

“Do you ever think about reconciling?” she asked one afternoon, stirring cream into her coffee.

“No,” I said. “Not even a little.”

“Not even gone to visit?” she pressed gently.

“I visited him every Saturday for forty-six years,” I said. “We called it motherhood. The visits just looked different.”

She laughed softly, then sobered.

“You really don’t feel guilty?” she asked.

“I feel sad that he chose this path,” I said. “But guilt? No. I did my job. More than my job. This part,” I gestured to the air between us, “this is his lesson, not mine.”

Abby moved out of state for work in October. My granddaughter. No blood relation, but Patricia’s daughter’s daughter. I’ve unofficially adopted them both. Funny how family finds you when you clear out the ones who only showed up to take.

One morning, standing in my kitchen with the kettle whistling and sunlight slanting through the window just right, I thought about that night in December, about the woman wearing my coat and my son’s hand on my shoulders. I thought about the crow at my frozen birdbath, pecking uselessly at ice.

Back then, I’d felt like that bird—desperate, confused, banging my beak against something hard and invisible. Now, with my tea in hand, my garden dormant but ready under the soil, friends who called because they liked me, not because they needed something, I realized something simple.

The ice had never been on the birdbath. It had been around my heart. Around my sense of self. Around my understanding of what I deserved. Breaking it hurt. Freezing your own children out of your life hurts in a way I can’t describe and hope you never have to feel. But once it cracked, once the water underneath could move again, everything else got a little easier.

I sat down at the kitchen table, opened my journal, and wrote four words.

“I choose myself now.”

Not in a selfish way. Not in a “to hell with everyone” way. In a quiet, steady way. In a “no more bleeding for people who don’t care you’re bleeding” way. In a “love is a two-way street, not a charity” way.

My name is Cordelia Whitmore. I am seventy-three years old. I am a widow. I am a retired teacher. I am a mother to a son who made choices I can’t rescue him from.

I am also the only person responsible for protecting my peace.

If I could reach back to that woman baking lemon bars on the day she saw the red coat at the ATM, I’d tell her this:

You are not crazy. You are not too sensitive. You are not selfish for wanting to be treated with basic respect. Your money is not their entitlement. Your kindness is not their right. Your home is not their safety net if they insist on cutting holes in it from the inside.

And if you’re sitting in your own kitchen right now, staring at statements or bruises or text messages that don’t add up, wondering if you’re overreacting, wondering if you’re allowed to be angry, wondering if drawing a line makes you cruel, let me tell you something I learned the hard way.

Saying “no more” is not cruelty. It’s self-respect.

Saying “you can’t treat me like this” is not abandonment. It’s survival.

Saying “I choose myself now” is not selfishness. It’s finally, finally choosing to live the years you have left in honesty instead of being slowly eroded by people who only come around when their mortgage bounces.

The phone still rings sometimes. Not as often. Different numbers now: telemarketers, doctors’ offices, friends. I answer when I want to. I don’t when I don’t.

The bruise on my wrist is gone. The ache in my ribs only flares up when I lift something too heavy. My heart still twinges sometimes when I see a red coat in a crowd or a son hugging his mother in the grocery store. But then I remember the kitchen floor, and the cold, and the words, and the choice I made.

I get up. I water my garden. I feed the crows. I make tea. I read books. I host book club. I laugh at silly things. I sleep at night.

I choose myself now.

News

CH1 Joy Reid Reposts Viral Video Calling “Jingle Bells” Racist, Sparking Fresh Debate Over Christmas Classic

NEW YORK — Former MSNBC host Joy Reid reignited a familiar culture-war debate this week after reposting a viral video…

CH1 “The Secret Weapon the U.S. Navy Hid on PT Boats — And Japan Never Saw It Coming”

The searchlights swept the black water like fingers. Lieutenant Commander Marcus “Mad Dog” Sullivan lay low behind the armored wheelhouse…

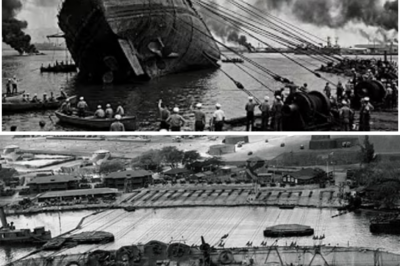

CH1 WWII’s Craziest Engineering: How the Navy Raised the Ghost Fleet?

The first thing you feel is the weight. Nearly 200 pounds of equipment presses down on your shoulders and hips….

CH1 They Mocked His “Medieval” Airfield Trap — Until It Downed 6 Fighters Before They Even Took Off

The first explosion tore through the dawn at 05:42. Then another. Then four more in rapid succession. Six RAF fighters…

Stepfather Beat Me For Refusing To Serve His Son I Left With $1—Now I’m Worth Millions

CHAPTER ONE THE HOUSE THAT LEARNED HOW TO PRETEND I’m Emma. I’m twenty-eight years old now, but this story begins…

CH1 ‘Selling Sunset’ Alum Christine Quinn Criticizes Erika Kirk’s Public Profile After Charlie Kirk’s Death

LOS ANGELES — Reality TV star and former Selling Sunset cast member Christine Quinn ignited fresh controversy this week after…

End of content

No more pages to load