The wind coming off the frozen hills of North Korea cut like a knife.

It was December 1950, somewhere near the Chosin Reservoir, and the 1st Marine Division was in a place every commander fears and few survive.

They weren’t outnumbered.

They were outnumbered, outgunned, and surrounded—by an estimated eight Chinese divisions.

Men were cold, exhausted, and scared. Trucks froze. Weapons jammed. The temperature dropped so low that breath turned instantly to ice on a man’s face.

In a command post dug out of frozen ground, Colonel Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller looked at a map, listened to the reports, and understood the truth:

There was no safe direction.

No open flank.

No easy way out.

A staff officer muttered, half to himself, “We’re surrounded.”

Puller’s response would become one of the most famous lines in Marine Corps history:

“We’ve been looking for the enemy for some time now.

We finally found him.

We’re surrounded.

That simplifies things.”

He wasn’t trying to be clever.

He was making a decision.

If there was no way around,

they would go through.

The man who gave that order, in that frozen hell, was not a West Point graduate.

Not a Medal of Honor recipient.

Not the polished product of some elite academy.

He was a small-town Virginian with a high school education, a busted-up body, and a chest full of ribbons that told the story of every dirty, miserable little war the United States had fought for thirty years.

His name was Chesty Puller.

And he earned the title “Marine’s Marine” the hard way:

From the front.

A Boy from West Point, Virginia

Long before anyone shouted “Chesty, Chesty!” in a barracks, there was just Lewis, the third of four children born in West Point, Virginia, on June 26, 1898.

His family roots dug deep into American soil.

English settlers in 1621.

A distant blood tie to George S. Patton.

That kind of lineage impresses people on paper.

Paper didn’t help when his father died in 1908.

At ten years old, Lewis wasn’t some young aristocrat dreaming about glory. He was a kid helping keep the family fed—selling crabs at a waterfront amusement park, working in a pulp mill, doing whatever the day demanded.

He kept going to school.

But life taught him faster than any classroom.

When he was 17, the world went to war.

Restless for a Fight

In 1916, Puller tried to join the Army to chase Pancho Villa across Mexico. He wanted in on the Punitive Expedition. Wanted the saddle, the dust, the danger.

His mother said no.

He was underage. She refused to sign.

When America entered World War I, he took a different path: an appointment as a state cadet at Virginia Military Institute. The deal was simple—financial support in exchange for future service.

He was, by all accounts, a mediocre student.

He went to ROTC camp. Studied. Drilled. Played the part.

But while he sat in classrooms, he read about Marines at Belleau Wood—about the 5th and 6th Marines stopping German offensives by sheer stubborn brutality.

That’s where he wanted to be.

Not in a lecture hall.

In a fighting hole.

So in August 1918, he left VMI and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps as a private.

He made it through Parris Island.

He impressed his commanders.

His test scores and his VMI time earned him a chance at Officer Candidate School.

On June 16, 1919, he pinned on gold bars as a reserve second lieutenant.

Ten days later, the war was over, the Corps shrank, and the Marine Corps handed him a brutal lesson:

He was put on inactive status and busted back to corporal.

Most men would have walked away.

Puller reenlisted.

Haiti: Learning to Hunt in the Dark

In June 1919, Corporal Puller went where the fighting still was—Haiti.

The Marines were running the Gendarmerie d’Haïti, a constabulary force fighting Cacos rebels in the hills and jungles. Puller served as a brevet lieutenant, effectively an officer in everything but formal paperwork.

He became adjutant to Major Alexander Vandegrift, a man who would later command the 1st Marine Division at Guadalcanal and eventually become Commandant of the Marine Corps.

It was in Haiti that Puller learned what would define his entire career:

Lead from the front.

Move at night.

Strike first.

He delivered supplies through areas crawling with insurgents. He used locals as intelligence sources. He changed the game by setting nocturnal ambushes instead of waiting to be attacked.

One night, after learning where a rebel camp was, he deployed his men in an L-shaped ambush—a skirmish line to the front, Lewis guns on the flank.

When the rebels walked into it, the Marines opened up.

Seventeen insurgents killed in a single night action.

Over time, Puller led more than 40 operations, killing over 200 insurgents, capturing dozens of weapons.

He wasn’t just fighting rebels.

He was unwittingly writing the manual on night ambush tactics.

Vandegrift noticed.

Back in the States in 1924, with his old CO’s support, Puller regained a regular commission as a second lieutenant.

He’d earned it in sweat and gunpowder.

Nicaragua: Earning the First Two Navy Crosses

In December 1928, the Corps sent him to Nicaragua as part of the National Guard detachment.

Different jungle.

Same job: fight local insurgents.

For two years he led patrols against bandits and guerrillas. He took the war to them, dragging Marines into the mountains and doing what he did best—closing with the enemy in rough terrain.

In mid-1930, for his actions under fire, he was awarded his first Navy Cross, the Navy and Marine Corps’ second-highest decoration for valor.

He went home, completed the Company Officers Course, then went straight back to Nicaragua.

He didn’t have to.

He wanted to.

In 1932, after another grueling deployment and a pitched battle against insurgents, he earned his second Navy Cross.

By that point, between Haiti and Nicaragua, he had logged more combat time than almost any company-grade officer in the Corps.

When most officers were studying tactics in classrooms, Puller was practicing them in the real world.

China, Nimitz, and a Narrow Road Up

In 1933, Puller joined the Marine Detachment at the American Legation in Beijing. He took command of the famed “Horse Marines”, riding mounted patrols in a city poised on the edge of chaos.

Later, he shifted to sea duty aboard the USS Augusta, a cruiser commanded by Captain Chester W. Nimitz.

Nimitz would one day oversee the entire Pacific Fleet in World War II.

Puller made an impression.

He didn’t have the pedigree.

But he had something generals notice:

He made problems smaller, not bigger.

In 1936, the Corps brought him back to the States to teach infantry tactics at The Basic School.

He was denied a seat at the Army’s Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth because he lacked a college degree.

Three years in the classroom.

No prestigious education.

No advanced diplomas.

Just a growing reputation as a man who understood combat in a way you couldn’t fake.

He returned to the USS Augusta, then went ashore again with the 4th Marines in Shanghai in 1940, commanding 2nd Battalion.

He married Virginia Montague Evans in 1937. They would have three children, including Lewis B. Puller Jr., who would later leave his own tragic, decorated mark in Vietnam.

In August 1941, with the world on the edge of a new war, Puller left China to take command of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines at Camp Lejeune.

Then came December 7th.

Pearl Harbor.

World War II.

Guadalcanal: “Chesty” in the Fire

In 1942, Puller sailed with his battalion to Samoa, then into the crucible that would define the early Marine war in the Pacific:

Guadalcanal.

Coming ashore in September, his men went straight into the meat grinder along the Matanikau River.

Under heavy attack, Puller coordinated with the destroyer USS Monssen, signaling for fire and rescue, helping extract trapped American forces. He earned a Bronze Star for his actions.

Weeks later, his battalion stood between Japanese forces and the one thing the Americans couldn’t afford to lose:

Henderson Field, the island’s vital airstrip.

On the night of October 24–25, 1942, Japanese forces hurled themselves at Marine and Army positions in wave after wave.

For three hours, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, alongside the 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry, held the line.

When it was over, the Marines and soldiers had suffered around 70 casualties.

The Japanese lost more than 1,400 dead.

Henderson Field held.

Puller received his third Navy Cross.

On November 8th, he was seriously wounded—shrapnel tearing into his arm and leg during a Japanese attack on his command post. He was evacuated, underwent surgery, and returned to command just ten days later.

One of the men under his command at Guadalcanal was Staff Sergeant John Basilone, whose heroism in securing the airfield earned the Medal of Honor—with Puller’s personal recommendation.

After Guadalcanal, Puller became executive officer of the 7th Marines and then went on to help lead Marines at Cape Gloucester in late 1943 and early 1944.

There, directing attacks through swamp, rain, and jungle filth, he earned his fourth Navy Cross.

In February 1944, he was promoted to full colonel and took command of the 1st Marine Regiment.

Then came Peleliu.

Peleliu: The Butcher’s Bill

In September 1944, the 1st Marines were ordered to assault Peleliu, specifically the nightmare terrain of Umurbrogol Ridge—a honeycomb of caves, ridges, and fortified positions.

It was one of the toughest assignments of the Pacific war.

Puller’s regiment fought through terrain that chewed up men and machines alike. The Japanese defenders were dug in deep, prepared to fight to the last man.

By the time the ridge was taken, more than half of Puller’s regiment were casualties.

He was criticized for ruthlessness, for pushing too hard, for leading from the front in ways that inflicted terrible losses.

But the ridge fell.

And the mission was accomplished.

At the same time, war found his family.

His younger brother, Samuel D. Puller, executive officer of the 4th Marines, was killed by a sniper on Guam.

Puller saw what every commander dreads: the war reaching into his own bloodline.

In November 1944, he left the Pacific to lead the Infantry Training Regiment at Camp Lejeune as the war wound down.

He had fought from Haiti and Nicaragua to Guadalcanal, Cape Gloucester, and Peleliu.

Most men would have called that enough.

Chesty Puller wasn’t most men.

Korea: Surrounded, Not Defeated

After World War II, he held stateside and regional commands—Pearl Harbor, reserve districts—serving wherever the Corps sent him.

Then, in June 1950, the Korean War erupted.

Puller once again took command of the 1st Marine Regiment.

He led them in the audacious Inchon landings in September, smashing into the flank of North Korean forces. His leadership earned him the Silver Star and a second Legion of Merit.

Then came the harshest test of his career.

Chosin Reservoir.

Late November.

Temperatures dropping below -30°F.

Chinese forces slammed into UN troops, encircling them in brutal mountainous terrain.

Between November 29 and December 4, Puller’s leadership under relentless attack earned him the Distinguished Service Cross from the U.S. Army.

From December 5–10, as the Marines fought their way out, he earned his fifth Navy Cross.

No one else in Marine Corps history has ever received five.

His men didn’t see decorations. They saw a commander who stayed close enough to the front to know exactly what they were facing.

They were cold.

Hungry.

Cut off.

He gave them something the enemy couldn’t touch:

The conviction that they could still win.

The General Without a Degree

In January 1951, Puller was promoted to brigadier general.

He briefly served as assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division, then took acting command when Major General O.P. Smith left.

He returned to the States in May, took command of the 3rd Marine Brigade at Camp Pendleton, and stayed on as it became the 3rd Marine Division in 1952.

In September 1953, he pinned on his second star as a major general and took over the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune.

He’d risen from enlisted Marine to three-star general without a college degree, without Leavenworth, without the traditional résumé.

He had something harder to quantify:

Combat credibility.

When Chesty Puller talked about infantry tactics, logistics, or leadership under fire, he wasn’t quoting a manual.

He was quoting scars.

The Body Gives Out, the Legend Grows

Years of campaigning in tropical climates, the lingering effects of malaria, and chronically high blood pressure tore at his health.

By 1955, his body had absorbed all it could.

On November 1, 1955, he retired as a lieutenant general.

He had:

Five Navy Crosses

One Distinguished Service Cross

Two Legions of Merit

A Silver Star

A Bronze Star

A Purple Heart

Few Marines have ever worn more combat decorations.

As for the nickname “Chesty”—Puller himself wasn’t sure where it started. Some said it referred to his barrel-chested stance. Others said it was pure Marine slang: “chesty” meaning cocky, bold, the man who stepped forward when others stepped back.

He retired to Virginia.

In October 1971, after a series of strokes, Lewis “Chesty” Puller died.

His story didn’t end there.

His son, Lewis B. Puller Jr., a platoon leader in Vietnam, lost both legs and parts of both hands to a mine. He received the Silver Star and Purple Heart, and later the Pulitzer Prize for his memoir Fortunate Son: The Healing of a Vietnam Vet.

In 1994, overwhelmed by pain and memory, he took his own life.

The wars Chesty survived had come home in another way.

The Ship and the Shadow

Today, the USS Lewis B. Puller sails as an expeditionary mobile base for the U.S. Navy—the second ship to carry his name.

Steel and engines can’t capture his character, but the ship carries his legacy forward: a platform meant to support Marines and special operations forces operating at the edge of danger.

Just like he did.

Why Chesty Stands Alone

Most Marine legends wear the Medal of Honor around their necks.

Chesty Puller never did.

He doesn’t need it.

His legacy isn’t a single moment or one spectacular act. It’s a lifetime of doing hard things in hard places:

Fighting rebels in jungles nobody remembers

Writing night ambush tactics with bullets instead of ink

Holding Henderson Field when losing it would have changed the Pacific war

Clawing his regiment through Peleliu’s killing ground

Leading Marines out of a frozen encirclement at Chosin by sheer will and audacity

He was rough.

He was ruthless.

He was far from perfect.

But to generations of Marines, he represented something simple and uncompromising:

A commander who would be with them when things got bad.

A leader who didn’t just study courage—he practiced it.

That’s why recruits still shout his name in cadence.

Why barracks stories still begin with “Chesty once said…”

Why, among all the generals and heroes, one name stands slightly ahead of the rest:

Chesty Puller.

The man who turned being surrounded into an advantage.

And meant it.

News

The tragic deaths of real-life Band of Brothers veterans George Luz, David Kenyon Webster and Bull Randleman.

By the time the world met them on television, most of them were already gone. The men of Easy Company…

The Most Dangerous Woman of World War II – Lady Death in World War II

At 5:47 a.m. on August 8, 1941, in the shattered streets of Beliaivka, Ukraine, a 24-year-old history student crouched behind…

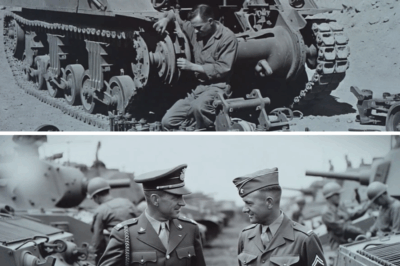

The Mechanic Who Turned an Old Tank Into a Battleground Legend

War had a way of turning machines into ghosts. In March 1943, somewhere in the empty heat of the North…

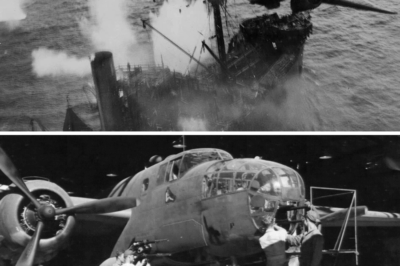

A Bomber with Fangs

The morning sky over the Bismarck Sea looked calm—too calm. A sheet of blue glass stretching to the horizon, broken…

Kicked out by her own family on Christmas with just one sentence—“You’re nothing to us”—Rowena walked away in silence. But five days later, her phone lit up with 45 missed calls. What changed? In this gripping family drama story, discover the buried secrets, the stolen inheritance, and the power of reclaiming your worth. This is more than a holiday betrayal—it’s a reckoning.

Part 1 – Before the Sentence Hi. My name’s Rowena. My family kicked me out on Christmas night. No screaming.No…

Colorado Mourns State Sen. Faith Winter: Environmental Champion, Policy Architect, Mother of Two, Killed in Five-Car Crash

Colorado’s political and civic landscape was jolted Wednesday night by the sudden death of State Sen. Faith Winter, a Democrat…

End of content

No more pages to load