War had a way of turning machines into ghosts.

In March 1943, somewhere in the empty heat of the North African desert, a Sherman tank named Iron Fist sat half-buried in sand, looking more like wreckage than a weapon. Its engine coughed instead of roared. Its transmission screamed in protest whenever anyone tried to move it. The armor was a diary of survival—gouges, scorch marks, and puckered craters where German rounds had come within inches of ending lives.

Most officers had already delivered their verdict.

Scrap it.

Cannibalize the parts.

Send the hulk to a depot and forget it ever existed.

But Private First Class Marcus “Mack” Henderson wasn’t most officers.

He wasn’t an officer at all.

He was just a mechanic sitting in the dust beside a broken tank with a grease-stained notebook in his hands and a look in his eyes that said the machine in front of him wasn’t done yet.

A Small-Town Mechanic in a Desert War

Before the war, Mack had never seen a Sherman. He’d seen tractors. Farm trucks. Rusted pickups nobody else in rural Pennsylvania wanted to touch. He’d fixed engines with parts that should’ve gone to the junkyard, rebuilt transmissions that other shops swore were hopeless.

He hadn’t graduated from any academy. No degrees. No fancy schooling.

But he understood machines.

He understood the way engines “breathed,” how fuel and air and compression turned into power. He knew how transmissions moved that power from crankshaft to track. Most of all, he knew how to listen—how a grinding noise, a knocking rhythm, a struggling idle was a language, not a death sentence.

The officer in charge of the motor pool, Captain James Richardson, had learned something else about war: paperwork didn’t keep men alive. Good machines did. Good people did.

When Richardson spotted Mack sitting cross-legged in the shadow of Iron Fist, sketching diagrams in his notebook, he recognized that look. The same look he’d seen when Henderson was solving “impossible” repair jobs.

“What are you thinking, Henderson?” Richardson asked, settling down beside him in the dirt.

Mack didn’t look up immediately. He drew one last line on the page, then closed the notebook.

“Sir, Iron Fist isn’t dead,” he said quietly. “She’s just tired and beaten up. I think I can rebuild her into something better than she ever was. Faster. Tougher. More reliable than any tank in the unit.”

Richardson snorted softly. “Every other officer in this command would say you’re wasting time and manpower. We’ve got a war to fight, not a custom shop to run.”

“Respectfully, sir,” Mack replied, “I think they’re wrong. The problem isn’t that she’s beyond repair. The problem is nobody’s actually looked at her. They see a damaged tank and calculate cost. I see a damaged tank and think about opportunity. There’s something to learn here. Something we can improve.”

Richardson studied him for a long moment.

He’d been around long enough to know that the best ideas in a war rarely started in headquarters. They started in foxholes. In tents. In motor pools, where grease and desperation forced men to improvise or watch their friends die.

“How long?” Richardson finally asked.

“Give me a month,” Mack said. “A month, access to the salvage yard, and permission to experiment. I think I can give you a tank that outperforms anything we’ve got.”

Richardson stood, brushed dust off his uniform, and looked at the battered Sherman as if seeing it for the first time.

“You’ve got your month,” he said at last. “But I’m holding you to it. If this doesn’t work, you’re helping me explain to the general why we turned a wreck into a science project.”

Mack grinned.

He had his chance.

Tearing a Tank Down to the Bone

Mack attacked Iron Fist like a surgeon with a patient no one else believed in.

He stripped the tank down to its chassis. The crew compartments were emptied. Panels were pulled off. Components laid out in neat rows on the desert floor. Every bolt, every weld, every line of cable and hose was inspected, tapped, or tested.

He found all the damage everyone expected to find.

But he also found something else:

Potential.

The engine, built to factory spec, had never been truly tuned for the heat and dust of the North African desert. The cooling system struggled. The carburetor choked. The intake manifold wasn’t breathing properly in the thin, scorching air.

So Mack rebuilt it.

He adjusted the fuel mixture. Modified the intake flow. Recalibrated the carburetor to keep the engine running strong when the mercury soared. He rerouted lines, polished surfaces, made changes that looked small on paper but meant everything under load.

Days boiled. Nights froze. Mack worked through both, often catching only a few hours of sleep, his head full of problems and solutions that wouldn’t let him rest.

Other mechanics shook their heads.

At midnight, by the light of a rattling lantern, they’d see him elbow-deep in some component most men would’ve just swapped out.

One evening, Tommy Peterson, another mechanic, found him buried up to the shoulders in the transmission housing, chasing down a grinding noise that had plagued the tank for months.

“Hey, Mack, you know there’s a war on, right?” Peterson joked, handing him a canteen. “You’re out here like you’re building a trophy for some mechanic’s competition.”

“Just fixing a machine, Tommy,” Mack muttered from inside the tank.

“Feels more like you’re marrying it,” Peterson said. “Seriously—what are you trying to turn Iron Fist into?”

Mack slid back, wiped grease across his sleeve, and looked at the hulk of Sherman looming over them.

“Better,” he said simply. “Every machine has potential people waste because they don’t take time to understand it. She can be faster. Tougher. More reliable. She just needs someone to believe that’s possible and figure out how.”

A Tank Reborn

Three weeks later, Iron Fist looked roughly the same from the outside.

But under the armor, she was a different creature.

The cooling system had been reworked to survive the desert. The track tensioners had been modified to prevent failures over rough terrain. The electrical system had been rewired for reliability. The turret traverse had been tuned and adjusted until the main gun swung faster and stopped truer on target.

When Captain Richardson came for his first real look at the finished tank, he almost walked past her.

Then Mack hit the starter.

The engine didn’t cough or wheeze.

It purred.

Deep. Smooth. Confident.

Richardson put a hand on the armor, feeling the vibration through his palm. “This is incredible, Henderson. How did you manage all this?”

“The math was sound, sir,” Mack said. “Once I understood what the engine needed, it told me what the transmission needed. Once the transmission made sense, everything else fell into place. Like a puzzle.”

They took Iron Fist into the desert for trials.

Mack pushed the tank harder than any sane man would with a standard Sherman—climbing dunes, pivoting on soft sand, running flat out. The engine stayed cool. The transmission shifted clean. The tracks bit and held instead of slipping and grinding.

The tank didn’t feel like a patched-together survivor.

It felt alive.

“This is exactly what we needed,” Richardson said when they rolled back into the motor pool. “Now we find out if it works where it counts.”

Trial by Fire

Three days later, the war came calling.

The unit was ordered to support an infantry assault on a German strongpoint. Anti-tank guns, dug-in positions, and crews who knew exactly how to kill Shermans waited ahead.

Mack wasn’t supposed to be there.

Richardson overruled that.

If anything went wrong with Iron Fist, he wanted the man who understood every nut and bolt sitting inside her.

Mack rode in the hull, just behind Sergeant Robert Collins, the tank commander, as they rolled toward the German lines.

The opening was textbook chaos.

German anti-tank guns barked as soon as the Shermans came into range. Standard tanks jerked to a halt, armor ringing and scraping as rounds slammed into them. Some backed away, damaged and limping. Others stalled, their crews fighting both the enemy and their own machines.

Iron Fist kept going.

Her rebuilt engine pushed through sand and shock. Her improved maneuverability let Collins weave and angle, making the tank a harder target. When a German gun flashed, Collins swung the turret—faster than any stock Sherman could—brought the main gun on line, and fired.

One gun position disappeared.

Then another.

Infantry poured through the gap Iron Fist had punched, flowing forward while German gunners fell or fled.

When they finally returned to the motor pool, dust-caked and deafened, Richardson was waiting, hands on his hips, wearing a grin he didn’t bother to hide.

“You proved something today, Henderson,” he said. “Good engineering isn’t about doing things the way they’ve always been done. It’s about understanding the problem deeply and then having the guts to think differently.”

Mack felt pride—but something else too.

Responsibility.

If this could be done once, it could be done again. The question wasn’t whether Iron Fist worked.

The question was:

Could this be a system, not a miracle?

From One Tank to Hundreds

Mack set out to make sure it could.

He documented everything.

Photos. Sketches. Measurements. Notes on why each modification was made and what effect it had in the field. He wasn’t just tinkering anymore.

He was building a method.

Other damaged tanks began appearing in his corner of the yard. Grey Ghost, battered in an earlier fight. Widowmaker, infamous for breakdowns and crew complaints.

They went into Mack’s process and came out different—quieter engines, smoother steering, more reliable systems. Crews noticed. They talked.

Skeptical mechanics became students.

Mack trained them not just to follow his steps, but to understand his thinking. Why this change? What does this sound mean? How does this system fail under stress?

Word spread up the chain.

Brigadier General Thomas Winslow eventually arrived, boots dusty, expression skeptical but curious.

“General, this is Private Henderson,” Richardson said, walking him through rows of modified tanks. “He’s been improving Sherman performance through systematic changes based on actual field conditions.”

Winslow listened. Watched. Rode in a few tanks himself.

Then he turned to Mack.

“How many could you do,” he asked, “if we gave you a dedicated team and the parts you needed?”

Mack thought before answering.

“Twenty tanks a month, sir. Maybe more once we streamline. Quality comes first. Speed follows.”

Winslow glanced over the motor pool—at the hulked wrecks, the half-repaired vehicles, the columns of dust where tanks rolled toward the front.

“We’ve written off hundreds of damaged tanks as junk,” the general said. “If we can bring even a fraction back—and have them perform better than the originals—that changes our tactical situation.”

He made his decision on the spot.

“I’m authorizing a special task force for this. You’re going to lead it, Henderson. Congratulations—you’re a sergeant now. I’ll send you the best mechanics I’ve got.”

Mack was stunned.

Richardson wasn’t.

“I told you good ideas get recognized eventually,” he said later. “Now you prove this isn’t a fluke. Now you turn one crazy project into a doctrine.”

A New Way of Thinking About Broken Machines

The task force grew fast—twenty mechanics at first, then more.

Mack taught them his philosophy:

Don’t just replace. Understand.

Don’t ask, “How do I get this back to factory spec?”

Ask, “How do I make this better for the way it’s actually used?”

They processed tank after tank. By late 1944, more than 500 vehicles had passed through their hands. Tank crews fought to get their names on the list for modified machines. Commanders noticed the numbers: higher uptime, fewer mechanical failures, better performance under fire.

Division staff officers came to observe. One of them, Lieutenant Colonel David Foster, spent a day watching the work and pulled Mack aside.

“What you’re doing here isn’t just fixing tanks,” Foster said. “You’re rewriting how maintenance works. You’re turning scrap into combat power. Mechanics into engineers. The Army is going to need people like you long after this war ends.”

Mack hadn’t thought much about after.

His world was engines, armor, and the men who trusted them with their lives.

He carried that weight heavily. At night, he’d sometimes sit alone on a crate, staring at the looming shapes of the tanks in the yard, wondering if he missed something—some flaw that would only reveal itself when armor was being lit by tracer fire instead of lantern light.

One of his men, Private Jones, found him there one evening.

“Rough day, Sarge?”

“Just thinking,” Mack said. “We’ve modified hundreds of tanks. What if we missed something in one of them? What if a flaw shows up when rounds start flying? That’s on me.”

Jones shook his head. “No, sir. It’s on us. We check each other’s work. We sign off together. If there’s a failure, we all own it. You taught us that.”

The knowledge didn’t get lighter. But it got shared.

By early 1945, as the war turned and the end drew nearer, Mack focused on more than performance. He reinforced weak armor points. Improved suspension to reduce strain. Designed better viewing systems for commanders and easier-to-use escape hatches for crews.

Not just tanks that fought harder.

Tanks that helped their crews survive when things went wrong.

An Offer He Turned Down

One day, General Winslow summoned Mack to headquarters.

The war was in its closing act. The general looked older—lines carved by years of bad news and hard decisions—but his voice was as sharp as ever.

“Sergeant Henderson,” he began, “the Army has decided something about your future.”

He laid it out plainly: they wanted Mack to go through officer training. To take what he’d learned and help build permanent programs after the war. Maintenance doctrines. Optimization programs. The kind of systemic changes that shaped entire armies.

Mack was floored.

He’d never imagined himself as an officer. He wasn’t a strategist. He was a man who listened to engines and read problems in grease stains and wear patterns.

“I’m honored, sir,” he said carefully. “But I’m not sure I’m the right man for it. I’m a mechanic, not a theorist.”

“You’re a problem solver,” Winslow corrected. “That’s what we need. Think about it. I’ll make the arrangements if you say yes.”

Mack did think about it.

He talked to Richardson. To his men. Wrote home, trying to explain an opportunity even he didn’t fully understand.

In the end, he declined.

In his letter back to the general, he wrote that his best work was done with tools in his hands and engines in front of him. He believed he could serve the Army—and the world—better by staying close to the machines themselves.

The war ended before anyone could argue.

A Quiet Life, Built on Wartime Lessons

In August 1945, when the news of victory finally reached the motor pool, Mack felt his world go sudden and strangely quiet.

No more rush of emergency repairs before a push. No more midnight overhauls for tanks needed at dawn. The clear, brutal simplicity of war—protect your people, fix their machines, repeat—evaporated.

He went home.

Back to Pennsylvania. Back to a small-town repair shop, an old boss, and offers of partnership and steady work.

He tried.

He fixed farm trucks and harvesters, tractors and factory engines. He did it well. But after months of living with machines that decided battles, it was hard not to feel like he was patching toys.

The old questions followed him:

What could this be if we improved it?

How much life is left in this machine?

What if “too old” is just “not understood yet”?

Six months later, he made his move.

Mack opened his own shop—a small, stubborn business dedicated not just to repair, but to modification and optimization. He sought out clients with aging equipment they couldn’t afford to replace. He offered something no catalog could sell:

“I’ll study what you’ve got. I’ll make it better. Cheaper than new. Stronger than before.”

Slowly, word spread.

By the early 1950s, his shop was known across the region. Customers drove for hours to bring him their problems. He hired mechanics and trained them in the same systematic thinking he’d used on Sherman tanks under desert suns.

He never advertised himself as a war innovator.

Most people knew him only as “that guy who can fix anything.”

The Historian Who Wouldn’t Let Him Disappear

For almost forty years, the Army’s records filed Mack’s work away under program names and technical codes. The story blurred into statistics—numbers of tanks modified, performance graphs, logistics reports.

Then, in 1984, a military historian named Dr. Elizabeth Chen started pulling at a loose thread.

She was researching American innovation in World War II when she found references to a “tank modification program” in North Africa that seemed oddly undocumented. No clear names. No headlines. Just hints.

After months of digging, she found him.

Marcus Henderson, age 67. Still running a modification shop in Pennsylvania. Still listening to machines.

When she walked into his shop and explained her project, Mack tried to brush it off.

“That was a long time ago,” he said. “Not sure I’m the right man to talk about ancient history.”

But Dr. Chen laid out what she’d found: how his methods had been copied in other theaters; how his approach had influenced postwar maintenance doctrine; how many vehicles—and by extension, lives—had been affected by what started as a “crazy project” in a desert motor pool.

“Whether you like it or not,” she said, “you’re part of World War II history.”

He finally agreed to talk.

During hours of interviews, he explained his philosophy in simple words that Dr. Chen later chose as the perfect summary:

“I wasn’t doing anything special,” he told her. “I was just looking at broken machines and asking what they could become if I took the time to understand them. Most people see a wreck and think ‘waste.’ I see potential. That’s not genius. That’s just refusing to write something off before you’ve really listened to it.”

Her book came out in 1987.

For the first time, his name appeared in military history journals. Museum curators wrote letters. Tank enthusiasts sought him out. The Army archives added his diagrams and manuals to their exhibits on wartime innovation.

Mack stayed in his shop.

The Legacy of Iron Fist

By the time he retired in 1992, at seventy-five, he had trained more than a dozen mechanics in his methodology. His business was the most respected modification shop in the region. Farmers, factory owners, and small business operators sent him letters thanking him for saving machines they couldn’t afford to lose.

Veterans wrote too—old men now—telling him about the modified Shermans they’d driven, the battles they’d survived.

On the wall of his shop, among the tools and yellowing photos, one thing hung framed and perfectly centered: a handwritten note from a young mechanic he’d trained.

“Thank you,” it read,

“for teaching me that every machine has potential,

and that one person with good ideas and determination

can change the world.”

Marcus “Mack” Henderson died in 1998, quietly, in his sleep.

His obituary in the local paper mentioned a few simple facts: mechanic, veteran, businessman. It didn’t talk about task forces, or generals, or hundreds of tanks reborn under his hands.

Most of his neighbors never knew.

But in military archives and museum collections, his work lives on—photographs of modified Shermans, hand-drawn schematics, training manuals, and formal commendations that all point to the same quiet truth:

Not all game-changing ideas come from men in large conference rooms.

Sometimes, they come from a mechanic in a hot motor pool, sitting in the dirt beside a wrecked tank that everyone else has given up on, and asking a simple, defiant question:

What if this isn’t junk?

What if this is the beginning of something better?

In the end, Iron Fist was more than a tank.

It was proof that in war—and in peace—the difference between scrap and salvation is often just one person who refuses to accept that “broken” means “worthless.”

News

The tragic deaths of real-life Band of Brothers veterans George Luz, David Kenyon Webster and Bull Randleman.

By the time the world met them on television, most of them were already gone. The men of Easy Company…

The General Who Never Got the Medal of Honor and Still Became the Most Famous Marine in History

The wind coming off the frozen hills of North Korea cut like a knife. It was December 1950, somewhere near…

The Most Dangerous Woman of World War II – Lady Death in World War II

At 5:47 a.m. on August 8, 1941, in the shattered streets of Beliaivka, Ukraine, a 24-year-old history student crouched behind…

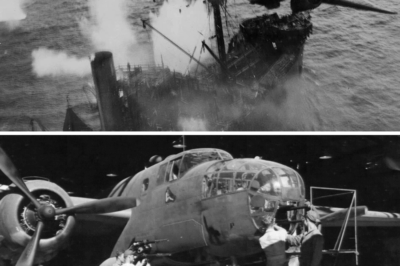

A Bomber with Fangs

The morning sky over the Bismarck Sea looked calm—too calm. A sheet of blue glass stretching to the horizon, broken…

Kicked out by her own family on Christmas with just one sentence—“You’re nothing to us”—Rowena walked away in silence. But five days later, her phone lit up with 45 missed calls. What changed? In this gripping family drama story, discover the buried secrets, the stolen inheritance, and the power of reclaiming your worth. This is more than a holiday betrayal—it’s a reckoning.

Part 1 – Before the Sentence Hi. My name’s Rowena. My family kicked me out on Christmas night. No screaming.No…

Colorado Mourns State Sen. Faith Winter: Environmental Champion, Policy Architect, Mother of Two, Killed in Five-Car Crash

Colorado’s political and civic landscape was jolted Wednesday night by the sudden death of State Sen. Faith Winter, a Democrat…

End of content

No more pages to load