In March 1943, somewhere in the North African desert, a Sherman tank named Iron Fist sat half-dead in the sand. Its engine coughed itself toward the grave, its transmission ground with a sound that made every mechanic within earshot wince, and its armor was scarred and blackened from too many close calls with German guns.

Most officers who walked past it saw scrap metal waiting to be hauled to a depot and stripped for parts.

Private First Class Marcus “Mac” Henderson saw something else.

He sat in the dirt beside the tank in the thin strip of shade it cast, a greasy notebook open on his knees, sketching little diagrams and notes while the desert heat shimmered around him. Mac wasn’t an engineer by training, had never seen the inside of a military academy. Before the war he’d worked in a small-town garage in rural Pennsylvania, fixing tractors and farm trucks that everyone else had given up on.

He knew machines the way some men know horses or weather. He could listen to an engine and tell you if it was tired, sick, or lying to you.

When Captain James Richardson, the motor pool CO, walked up and saw that look on his face—the furrowed brow, the faraway stare that usually meant he was halfway through solving a problem no one else knew existed—he dropped down beside him in the sand.

“What are you thinking, Henderson?”

“Sir, Iron Fist isn’t dead,” Mac said, still looking at his sketch. “She’s just tired and beat up. I think I can rebuild her into something better than she was before. Faster, tougher, more useful than any tank we’ve got in this unit.”

“Every other officer in this command would tell you you’re wasting time,” Richardson replied. “We’ve got a war to fight. We don’t have a month for pet projects.”

“Respectfully, sir, I think they’re wrong,” Mac said. “The problem isn’t that Iron Fist is beyond repair. The problem is nobody’s really looked at her. They see a damaged tank and think cost. I see a damaged tank and think potential.”

Richardson studied him for a long moment, then looked up at the hulking Sherman. He’d been in the Army long enough to know where the real ideas came from. Not from headquarters, but from the men who lived with the failures.

“How long do you think it would take?”

“Give me a month,” Mac said. “Access to the salvage yard, freedom to experiment with a few modifications, and I’ll give you a tank that’ll outrun and outfight any stock Sherman you’ve got.”

Richardson rose, brushed off his pants, and nodded slowly.

“You’ve got your month,” he said. “But if this thing doesn’t perform, you and I are going to be standing in front of a general explaining why half my crew spent a month babysitting a junkyard queen.”

Mac grinned.

“Yes, sir.”

He threw himself into the work like a man possessed. He stripped Iron Fist down almost to her bones, pulling armor plates, yanking the engine, opening the transmission, examining every weld and bearing and shaft. He found damage nobody had logged—cracked mounts, worn-out seals—but he also saw opportunities no one had thought to chase.

The stock engine had been designed for average conditions, not for the thin, hot air of North Africa. Mac tore it down, then rebuilt it from the crankshaft up: adjusting fuel mixture for desert heat, modifying the intake manifold, recalibrating the carburetor, improving the cooling flow so it wouldn’t boil over at noon.

While other men slept in tents or foxholes, he worked by lamplight with a wrench in one hand and his notebook in the other. At night other mechanics would pass by and shake their heads.

One evening, Tommy Peterson found him with his torso half-buried in the transmission bay, grease up to his elbows.

“Hey Mac, you know there’s a war on, right?”

“Just fixing a machine, Tommy,” Mac said.

“You’re gonna burn out your brain doing it,” Peterson replied, handing him a canteen. “What are you actually trying to turn this thing into?”

“Better,” Mac said simply. “Every machine’s got potential that gets wasted because people don’t listen to it long enough. Iron Fist can be faster, tougher, more reliable. She just needs someone willing to take her seriously.”

After three weeks of this, Iron Fist didn’t look dramatically different from the outside, but under her battered skin, she was practically a new creature: a cooling system reworked to handle desert punishment, a strengthened track tension system, upgraded wiring for reliability, gun mounts tweaked for faster traverse and finer control.

When Richardson came back to inspect, he barely recognized the sound of the engine when Mac hit the starter. It didn’t cough. It roared, then settled into a smooth, confident rumble.

“This is incredible, Henderson,” Richardson said, hand resting on the warm armor. “How did you pull this off?”

“The math was sound, sir,” Mac said. “Once I understood what the engine wanted, the transmission told me what it needed. After that, the rest just lined itself up.”

They took Iron Fist out into the open desert for a shakedown. Mac stood in the commander’s hatch while Sergeant Robert Collins drove. Richardson rode along, hanging on to whatever he could. Collins pushed the tank hard, faster and farther than he ever dared take a Sherman.

The tank responded like it was finally being asked to do what it had been born for. The engine didn’t strain; it thrummed. The gears shifted smooth; the tracks bit and tracked instead of dragging. Richardson felt the difference in his bones.

“This is exactly what we needed,” he said when they rolled back in. “Now we’ll see if the Germans agree.”

Three days later, they did.

The unit was ordered to support an infantry attack on a dug-in German strongpoint. Richardson insisted Mac ride with Iron Fist. If anything failed, he wanted the man who built her inside.

They rolled forward into a wall of sand and heat and 75mm German shells. The first Shermans in the line took hits and backed off, armor gouged, crews rattled, confidence shaken. Anti-tank guns zeroed their lanes and waited for the next target to lumber into them.

Iron Fist didn’t lumber.

Collins kept her moving, swinging the hull left and right, never presenting the same angle twice. The extra power in the rebuilt engine let him surge and dodge in ways the German gunners didn’t expect from a Sherman. The modified gun mount let him swing the turret quicker and get on target before the other drivers could even call out bearings. Shells that would have landed on a slower tank smashed into empty sand. Iron Fist’s rounds found their mark.

One by one, the German guns went silent.

The infantry behind her moved up through the breach she’d opened.

When they got back to the pool, Richardson was waiting.

“You just proved something important today, Henderson,” he said as Mac wiped sweat and grease from his face. “Good engineering isn’t about following regulations. It’s about understanding the problem deeper than the people who wrote the regulations.”

Mac felt pride, sure, but also the stirrings of responsibility. If this worked once, could it work again? Could you make a pattern out of what had begun as one man’s obsession?

Over the next weeks, he wrote everything down: schematics, parts lists, before-and-after performance numbers. He didn’t treat it like magic. He treated it like a system.

He started training other mechanics. At first, some resented it—this private acting like a professor, talking about fuel-air ratios and torque curves. Skepticism didn’t last. Not after they drove tanks that had gone through “Henderson’s process.”

Grey Ghost went in as a limping wreck and came out running smoother than new. Widowmaker, notorious for breaking down, returned from Mac’s bay and didn’t spend another day on the sick list.

Brigadier General Thomas Winslow eventually came down to see what he’d been hearing about. Richardson walked him past rows of tanks, some standard, some with Henderson’s subtle fingerprints. They watched Iron Fist and a couple of her sisters tear across the sand, pivot, fire, re-engage.

“Private, how many tanks could we modify if we invested in this?” the general asked afterward.

“If you gave me a team and salvage access?” Mac said, choosing his words carefully. “Twenty a month. Maybe more if we streamline. But the quality won’t suffer. That’s non-negotiable.”

Winslow nodded slowly, mind already chewing on numbers.

“We’ve got hundreds of damaged tanks rotting in lots,” he said. “If we can get even a fraction back in fighting shape and better than before, that changes the board. I’m setting up a task force. You’re leading it.”

“Sir?”

“You’re a sergeant now,” Winslow said. “You’ll get the best mechanics I’ve got. I expect monthly reports. Don’t make me regret this.”

The promotion felt strange on Mac’s shoulders, but it didn’t change what he did when he woke up the next morning. He still walked into the motor pool, smelled oil and dust, and reached for a wrench. Now he had twenty men to bring along with him.

He didn’t just tell them what to do. He told them why. He explained every modification, made them think through cause and effect, trained them to listen to noisy gearboxes and lazy carburetors and ask, “What are you trying to tell me?”

Word leaked out. Units began to request “Henderson tanks.” Division staff officers took notes. A lieutenant colonel from logistics watched for a full day and then said quietly:

“You realize this is bigger than North Africa, right? This is a blueprint for how maintenance ought to work.”

Mac shrugged.

“It’s just fixing things right,” he said.

By late 1944, the task force had processed over 500 Shermans. In after-action reports, commanders noted fewer breakdowns, better acceleration, quicker turret response, and crews who trusted their machines more. The Army copied his model, setting up similar teams in Italy, in England, later in France. Henderson spent as much time traveling and teaching as he did holding a wrench.

Some nights, the weight got to him. Sitting outside the bays after hours, watching the desert sunset flare and fade, he admitted to Jones, one of his best men:

“Sometimes I lie awake thinking, what if we missed something? What if one of these tanks fails because I didn’t look close enough?”

“We all look close,” Jones told him. “We all sign off on the work. If something fails, it’s on all of us. That’s how this works, Sarge.”

In early 1945, as the war ground toward victory, Henderson’s focus shifted a little. He began thinking not just about performance, but survivability: reinforcing known weak points in the armor, adding bracing to hatches, tweaking suspension to take rough ground without punishing the crew, small changes that made it easier for men to live through hits instead of dying inside their machines.

One day, General Winslow called him in. The general looked older, like someone who’d seen too many casualty lists.

“Sergeant, the Army wants you to consider OCS,” he said. “We need officers who think like you. Not just about guns and glory, but about systems and sustainability.”

“I’m honored, sir,” Mac said. “But I’m not sure I belong behind a desk. I’m a mechanic. A teacher, maybe. Not a strategist.”

“You’re a problem solver,” Winslow corrected. “That’s what we need.”

Mac thought about it for weeks. He wrote home. He talked to Richardson, to the men in his bay. In the end, he turned it down. In his letter to the general, he wrote that he believed he could do more good with a wrench in his hand and a group of mechanics around him than with a bar on his shoulder and a stack of paperwork on his desk.

In August 1945, when the war finally ended, he got the news standing in front of a stripped-down hull, pencil behind his ear. The sudden absence of urgency left him hollow and relieved all at once.

Back in Pennsylvania, his old boss at the garage took him on as a partner, grateful to have him back. But after months, Mack realized that just repairing things to spec wasn’t enough anymore. His brain kept looking for improvements: how to make an old thresher run cooler, how to give a delivery truck better fuel economy, how to extend the life of a combine that should’ve already died twice.

So he opened his own shop—a narrow building with one bay and a hand-painted sign advertising “Equipment Modification & Optimization.”

He didn’t just fix broken parts. He asked customers:

“What do you need this machine to do that it can’t do now?”

Then he tried to make it happen.

Farmers brought him tractors with bad reputations. Factory owners brought aging presses. Small-town trucking firms brought dying rigs. He examined each like he had examined Iron Fist, looking past the scars.

The business grew. Slowly at first, then by word of mouth. By the early 1950s, people were hauling machines from three states over for “Henderson work.” He hired young mechanics and taught them the same way he’d taught his wartime team.

He didn’t talk about Africa. When the conversation drifted toward the war—because it always did, with men of that generation—he’d wave it off with:

“I worked in a motor pool,”

and steer the topic back to carburetors.

It wasn’t until 1984 that history came knocking.

Dr. Elizabeth Chen, a military historian, drove out to his shop with a stack of photocopied reports. She’d found scattered references to a North African tank modification program that had quietly doubled the combat readiness of several armored battalions—and then seemingly vanished from the record.

“Sir, your work changed how the Army thinks about maintenance,” she said. “It influenced postwar doctrine. It’s in the bones of how they do logistics today. Whether you like it or not, you’re part of that story.”

“That was a long time ago,” Mac said. “I’m not sure anyone needs to hear about old war tricks.”

She kept coming back. Finally he let her sit at the cluttered desk in his office and turn on a tape recorder. She asked detailed questions. He answered as much as he could remember, walking her through his thought process.

“I wasn’t doing anything special,” he told her at one point. “I just looked at a busted machine and asked what it could be if I took the time to listen to it. Most folks look at a broken tank and see junk. I looked at them and saw potential. That’s not genius. That’s just refusing to give up on something because someone else already has.”

Dr. Chen’s book came out in 1987. For the first time, Marcus Henderson’s name appeared in print as more than a line in a unit roster. Tank enthusiasts wrote him letters. Museums asked for copies of his notes. The Army invited him to speak, which he politely declined.

He kept coming to the shop every morning until 1992, when he finally retired at seventy-five, handing the keys to a younger man he’d trained.

On one wall of that shop, among framed photos of family and grease-smudged schematics, one yellowed note stayed pinned up until the day he closed the doors. It was in a young mechanic’s handwriting.

“Thank you,” it read, “for teaching me that every machine has potential, and that one person with good ideas and determination can change the world.”

When he died in his sleep in 1998 at eighty-one, the local paper in town ran a short obituary. It said he was a mechanic, a veteran, and the owner of a successful equipment modification business. It didn’t mention Iron Fist. It didn’t mention North Africa or the programs that spun off his notebook sketches.

Most of the people at his funeral had no idea that decades earlier, in a desert on the far side of the world, the quiet old man who fixed their hay balers and delivery trucks had looked at a broken tank and refused to let it die—and in doing so, taught an army how to think differently about every broken machine they’d ever dragged off a battlefield.

News

SOME CULTURES THAT SHOULD NOT BE WELCOME IN THE UNITED STATES

Congresswoman Omar is a very clever person – either she is being protected by the Democratic Party or they are…

Jasmine Crockett Calls for Tax Exemption for Black Americans

December 9, 2025 — Washington, D.C. A reposted podcast clip from 2024 is going viral on X today, with many…

Michigan Woman Demands $250,000 After Police Remove Her Hijab During Booking — Officers Say She Was Arrested Over Fraudulent Plates, Illegal Weapon

A Michigan woman is demanding $250,000 from the City of Ferndale after police required her to remove her hijab during…

Jim Carrey Revives His Most Stinging Trump Takedown: “He Didn’t Make America Great Again — He Just Turned Back the Odometer”

Actor and comedian Jim Carrey is once again lighting up social media with a blistering rebuke of President Donald Trump,…

Alina Habba Resigns as U.S. Attorney for New Jersey After Court Battle Over Her Appointment

NEW JERSEY — After months of legal turmoil and mounting judicial backlash, Alina Habba has stepped down as Acting U.S….

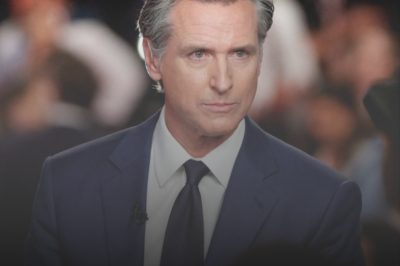

A Balanced Look at Governor Gavin Newsom’s Record: Ambition, Achievements, and a California Divided

California Governor Gavin Newsom has long been framed as one of America’s most charismatic political figures—an image reinforced by his…

End of content

No more pages to load