You are standing in a war room somewhere in France. It is late November 1944.

The walls are bare plaster or canvas stretched over wooden frames. A few lightbulbs hang from wires. The air smells like cigarette smoke, coffee that’s been sitting too long, and wet wool steaming dry near a small iron stove. Outside, snow has started to fall in soft, steady flakes. Inside, everything is maps.

Maps on the walls. Maps on tables. Maps clipped to boards and pinned to crates. They’re covered with grease pencil marks. Blue arrows for Allied positions. Red symbols for German units. Dashed lines for supply routes. Neat circles around towns you’ve only ever seen in newspapers.

At the main table, General George S. Patton bends over the big map like he’s trying to will it to change by staring at it hard enough.

He’s fifty-nine. Lean, sharp-featured, restless. His hands move over the paper, tracing axes of advance, tapping at river crossings, nudging units forward as if he can push them east by touch alone. His voice, when he speaks, cuts through the low murmur of the room.

He wants to drive into Germany as fast as fuel and roads will allow.

He wants to end this war by Christmas.

Around him, staff officers jot notes, flip through notebooks, and move markers. They know their boss. His whole presence radiates forward. He hates waiting, hates caution, hates anything that feels like standing still.

In one corner, at a smaller desk half-buried in paper, sits a man almost easy to miss.

Colonel Oscar W. Koch, Third Army G-2. Patton’s intelligence officer.

He doesn’t look like he belongs in a Patton story. He’s not loud. He’s not glamorous. He wears glasses. His posture is careful. His hands move in small, precise motions through stacks of reports, prisoner interrogation transcripts, aerial reconnaissance photos, radio intercept summaries.

He doesn’t command divisions. He commands information.

Right now, those pages in front of him are telling him something he doesn’t like.

He reads. He underlines. He reaches for another folder. A pattern he’s been feeling in the back of his brain for days clicks into place like a final puzzle piece.

He clears his throat.

“Sir,” he says.

The noise in the room tapers off. Patton looks up.

“I believe the Germans are preparing a major counteroffensive,” Koch says quietly. “Possibly through the Ardennes. Soon.”

The room goes still.

Someone chuckles, short and awkward. Another officer shakes his head.

Everyone “knows” the war is almost over. Germany is beaten. Their fuel stocks are nearly gone. Their divisions are shadows. Their soldiers are old men and boys. The idea that they could mount a large-scale offensive in the dead of winter through a forest most people treat as a rest sector? It sounds crazy.

Patton doesn’t laugh.

He focuses on Koch.

“Show me,” he says.

George S. Patton was born loud.

From childhood he devoured military history. Alexander. Hannibal. Napoleon. He believed war was the ultimate test of character and that he was meant to take that test. He went to West Point. He fenced. He rode. He competed in the modern pentathlon in the 1912 Olympics. In World War I, he joined the brand-new Tank Corps, fell in love with steel and speed, and served under Pershing in France.

Between wars, when other officers treated peacetime as a holding pattern, Patton studied. He read everything from cavalry manuals to ancient campaigns. He believed that war favored speed and shock, that movement and aggression saved more men than hesitation and caution ever did. He wrote about armored warfare before most people could even imagine long lines of tanks racing across a front.

By 1943 and ’44, his reputation had hardened. Brilliant. Difficult. Profane. Inspiring. Infuriating. He drove his men hard and himself harder, always toward the enemy.

Oscar Koch was born quiet.

He did not grow up dreaming of glory. He ended up in intelligence work—an unglamorous specialty at the time. Intelligence officers didn’t lead charges. They read. They listened. They sifted lies and half-truths into something useful, then tried to convince commanders to pay attention.

Koch was good at it.

He learned to read reports not as individual stories but as pixels in a bigger picture. Ten prisoner interrogations that all mentioned “a new unit in the sector.” A few railroad movement reports that didn’t quite fit supply patterns. Intercepts with call signs nobody recognized. He learned to distrust hope. He learned that the most dangerous enemy wasn’t the one in front of you—it was the one you had convinced yourself could no longer do anything.

North Africa. Sicily. Normandy. In each campaign, he refined his craft. Collected, evaluated, warned. Over time, he and Patton—a man made of volume and momentum and a man made of pencil lines and quiet conviction—built something rare.

Trust.

Patton listened because Koch didn’t sugarcoat. Koch spoke because Patton was one of the few who actually did something with what he said.

By late November 1944, that partnership was about to be tested.

The summer had been triumph.

After the breakout from Normandy in July—Operation Cobra—Third Army had erupted out of the bocage like water through a broken dam. They raced across Brittany, liberated town after town, scooped up prisoners by the tens of thousands, and captured fuel dumps the Germans hadn’t had time to destroy.

French civilians threw flowers. Reporters scribbled copy about “Old Blood and Guts” and his unstoppable tanks. Patton’s men covered in days what World War I had measured in months.

By autumn, Third Army was pressing against the German border. Snow dusted the Vosges and the Ardennes. Leaves fell. And across the Allied high command, a belief settled in like fog.

The war was almost over.

Allied intelligence estimates said Germany had burned through most of her fuel. Production plants were rubble. Divisions were understrength. The Luftwaffe had been pounded from the sky. All that remained, many thought, was to push steadily, accept surrender, and figure out what Europe would look like afterward.

At SHAEF—Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force—staff officers wrote careful, optimistic assessments. Germany, they said, lacked the capability for a major offensive in the West.

Koch was uneasy.

He sat in that cramped corner in that chilly war room, night after night, going through stacks of paper. Prisoner interrogations. Aerial reconnaissance. Radio intercepts. Logistics reports. Nothing by itself screamed. Together, they whispered.

German divisions that should have been shattered were being pulled out of line and disappearing.

Rail movements from the east showed tanks heading west, not to plug gaps, but to positions behind quiet sectors.

Signals traffic increased in areas that weren’t seeing fighting.

Fuel and ammo seemed to be quietly accumulating in depots near the Ardennes.

Recon flights that tried to take a look sometimes got turned back by flak or bad weather at just the wrong time.

Individually, each piece could be explained away. Replacement units. Defensive preparations. Local counterattacks.

Koch did what he always did.

He put them on a map.

Unit markers here. Railroad sightings there. Supply dumps. New call signs. When he stepped back, the pattern made his stomach go cold.

The Germans weren’t just hanging on.

They were massing.

And the place where they were massing—behind a forested, hilly stretch held thinly by tired American divisions on rest—looked a lot like a springboard.

He finished his analysis. He walked into Patton’s office.

“Sir, I believe the Germans are preparing a major counteroffensive, possibly through the Ardennes soon.”

Patton listened to the briefing. Koch laid out the missing divisions, the unusual rail activity, the quiet buildup, the weather patterns that would ground Allied fighters.

“How sure, Oscar?” Patton asked.

“I can’t be certain,” Koch said. He wasn’t a fortune-teller and refused to pretend. “But the capability is there, and the conditions are favorable. If I were in their place and wanted to hit us, that’s where I’d go, and that’s when I’d do it.”

Some of Patton’s staff officers shifted uncomfortably. One pointed out that SHAEF intelligence did not share this assessment. Another noted that the Germans were on the ropes; surely they wouldn’t squander precious armor on a wild gamble.

Patton waved them down.

“If you’re right and we do nothing,” he said to Koch, “we lose men. If you’re wrong and we prepare, we lose some staff time and a little fuel.”

He made up his mind.

“Draw up contingency plans,” he ordered. “If they hit in the Ardennes, I want Third Army ready to pivot north and smack them in the flank. Not in a week. In forty-eight hours. Seventy-two at most.”

Around the room, heads turned.

Turning an entire army ninety degrees in winter—tanks, trucks, guns, fuel, food—was not something normal people planned to do on two days’ notice.

Patton’s tone said he wasn’t asking if it could be done.

He was telling them to figure out how.

So they did.

For the next two weeks, while most of the Allied command dreamed of pushing east and being home by Christmas, a handful of officers in Third Army headquarters burned midnight oil over maps.

They charted routes north. They identified choke points where traffic control would be critical. They pre-allocated fuel stocks. They picked assembly areas. They wrote orders with blanks in them for dates and times.

Most of them thought it was an exercise, a form of intellectual insurance against one of their boss’s darker hunches.

Koch didn’t.

On December 16th, 1944, just before dawn, in an eighty-mile stretch of silent woods called the Ardennes, German artillery announced who had read the situation correctly.

Thousands of shells fell on American positions. Fog and low cloud made the explosions feel closer. Units that thought they were in “quiet” sectors saw their foxholes torn to pieces.

Then the tank engines started.

Panthers. Mark IVs. Jagdpanzer assault guns. Columns of infantry riding them or trudging through the snow behind. They slammed into regiments and battalions strung out thinly along roads and ridges.

Communications failed. Phone lines were cut. Radios jammed or overwhelmed. In some places, the first solid indication that something was wrong was when a German armored spearhead rolled right through an American headquarters.

By mid-day, desperate reports were coming in from First Army. Massive German attack. Multiple penetrations. Unknown strength. Some units outflanked. Some surrounded. Some simply gone.

At SHAEF, the reaction was shock.

“This can’t be real,” one officer muttered.

The intelligence estimates had said “no capability.”

Reality didn’t care.

Historians would later call it an intelligence failure.

At Third Army headquarters, Patton didn’t waste time being surprised.

He looked at Koch.

No smugness there. Just something like grim confirmation.

“When do we move?” Patton asked.

“We can issue orders now,” Koch answered. “Routes are laid out. Fuel’s been identified. It’s up to you, sir.”

Patton called an operations conference at Verdun. Other commanders arrived expecting to talk about how to keep pushing east. Eisenhower asked how soon anyone could strike north.

Most generals asked for days.

Patton said, “I can attack with three divisions in forty-eight hours.”

They thought he was bragging.

He wasn’t.

He’d already given the alert. Movement orders were written. Quartermasters knew which depots to hit. MPs knew where to stand along frozen French roads to keep trucks and tanks flowing north instead of east.

In the bitter cold of mid-December, with snow turning roads into slick ribbons, Third Army turned.

If you were a GI in one of those divisions, it felt like whiplash.

You’d been fighting for weeks, maybe months. You’d been told your unit finally had a breather. Maybe there’d be hot food, a cot out of the mud, a chance to read a letter from home twice without somebody shouting “saddle up.”

Then, just after midnight, the word came down.

“Pack up. We’re moving. North.”

No explanations. No big speeches. Just orders and a long line of trucks with engines already running.

You threw your gear in a duffel, slung your rifle, and climbed into the back of a deuce-and-a-half with thirty other men. The canvas blocked the worst of the wind; it didn’t block much.

Convoys stretched for miles. Headlights hooded, taillights dim, chains clanking on tires. Tanks crawled along the same roads, occasionally sliding sideways on icy curves. Any vehicle that broke down got shoved into a ditch. There was no time to coax sick engines back to life.

Men huddled together for warmth, breath steaming in the dark. Nobody really knew where they were going. They just knew someone up the line was in trouble.

They covered more than a hundred miles in two days.

On December 22nd, Patton’s vanguard hit the southern flank of the German bulge near a town called Bastogne, where the 101st Airborne and a handful of tank destroyer battalions and other odds and ends had dug in and refused to move.

On December 26th, a Sherman tank from the 4th Armored Division named “Cobra King” made contact with the Bastogne defenders.

The siege was broken.

The German offensive—the Ardennes Offensive, the Wacht am Rhein—the Battle of the Bulge—began to sag and then crumble under pressure from three directions. The bulge shrank. The red arrows on the big maps retreated back to their own border.

By late January, it was over.

Germany had spent fuel, tanks, and men it couldn’t replace on a last roll of the dice.

The war in Europe would grind on into May, but after the Bulge, its outcome was no longer in doubt.

Thousands of Americans who had been surrounded in snow and fog in December walked out alive in January.

They owed that to a lot of people. To the men in the foxholes who said “Nuts” when asked to surrender. To truck drivers who white-knuckled frozen roads. To mechanics who kept engines running in temperatures that made metal brittle.

They also owed it to the man in the corner of a war room who said, “There is danger coming,” and to the general at the center of that room who believed him when almost nobody else did.

You don’t see Oscar Koch in most pictures of the Bulge. He isn’t in the famous photos of Patton at the front, or the shots of relieved paratroopers shaking hands with grinning tankers.

He’s back at a desk, mapping where the German armored spearheads actually are, not where people hope they are. He’s reading new prisoner interrogations. He’s adjusting his estimate of how much fight the enemy has left. He’s doing the same work he was doing in November. Quietly.

In the postwar debriefs and histories, “intelligence failure” became a phrase attached to the Bulge like a label. How, people asked, could the Allies miss so much?

Koch knew the answer.

It wasn’t that the signs weren’t there.

It was that most people, seeing those signs, chose not to believe them.

In the late 1960s, long retired, Koch sat down with a journalist named Robert Allen and wrote G-2: Intelligence for Patton. In it, he tried to explain how he worked. Collect broadly. Evaluate coldly. Think in terms of capability, not assumed intention. Speak truth upward even when it won’t get you invited to parties.

He was sometimes called “Patton’s oracle.”

He shrugged that off.

He didn’t claim mystic insight. He claimed only that he’d added up what the enemy could do and warned people that they might try to do it.

The tragedy, he said, was not that people failed to collect information.

It was that commanders failed to listen to the information that made them uncomfortable.

Patton was the exception.

Patton had his faults—God knows there are books about them. His temper. His ego. The slapping incidents. The belief in reincarnation and destiny.

But in that cold French room, staring at a map, he did something that doesn’t fit neatly into the caricature.

He listened to the quietest man in the room.

And he acted.

After the war, Patton died in a car accident in Germany in December 1945, a few months after victory in Europe. He was buried among the men his tanks had led.

Koch lived on, quietly, without parades. Within the small world of military intelligence, he earned respect. Outside it, his name faded behind bigger ones.

If you pull back from the tanks and snow and shells, the story they wrote together is not just about the Battle of the Bulge.

It’s about a pattern you can see anywhere humans are trying to steer something big.

There are always Pattons—people who want to charge ahead, who thrive on momentum, who believe that boldness itself is a strategy.

There are always Kochs—people who sit in corners with data, who notice things that don’t fit the story everyone else is telling themselves, who feel an obligation to say, “Wait. Something’s wrong.”

Wars are often won not by the loud man or the quiet one alone, but by what happens when the loud man stops, even briefly, and says, “All right. Show me.”

Companies rise or crater based on whether the person at the top hears the analyst who says, “These numbers don’t work.” Families survive or fracture based on whether someone listens when another person says, “We need to address this, even if it hurts.”

So here’s the part where the history lesson turns out to be about you.

In your life, who’s your Koch? Who’s the person who sees the thing you’re incentivized not to see? Who’s telling you a story you don’t want to hear?

And are you Patton only when it’s fun—only when “forward” matches your hopes—or also when “forward” means stopping, turning, and admitting you were wrong about where you thought you were going?

Thousands of men walked out of the Ardennes alive because one general trusted one intelligence officer at the right moment.

In all the untold cases where people didn’t, we don’t have monuments. Just consequences.

Patton’s greatest moment may not have been a charge. It might have been the moment he tapped a map, looked at a quiet man with a stack of reports, and said, “I believe you. Let’s prepare.”

Koch’s legacy isn’t in marble. It’s in ordinary men who came home, had kids, coached little league, yelled at traffic, and told stories on porches—men whose lives would have ended in frozen foxholes in December 1944 if their commander hadn’t listened to a voice most people were trained to ignore.

That’s what responsibility looks like when you strip away uniforms and flags.

The storm comes either way.

The only real question is whether you let the quiet voice warn you in time.

News

CH1 The Mud Trick One British Engineer Used to Blind a Panther Platoon

On the morning of July 14th, 1944, Royal Engineer Harold Bowmont knelt in a flooded Norman ditch, mixing clay and…

CH1 German Command Laughed at this Greek Destroyer — Then Their Convoys Got Annihilated

In 1941, every navy in the world agreed on one thing. You do not send obsolete ships into modern war….

My PARENTS And SISTER Refused To Take My DAUGHTER To The ER ‘After She Broke Her LEG’ And Made Her…

Chapter 1 The Things I Pretended Not to See For a long time, if you’d asked me to describe my…

CH1 They Mocked His P-51 “Knight’s Charge” Dive — Until He Broke Through 8 FW-190s Alone

December 1944, the winter sky over Germany was a killing ground. At 28,000 feet, the cold bit through leather and…

CH1 Jimmy Kimmel’s Renewal Rebellion: Inside ABC’s High-Stakes Showdown With Trump, the FCC, and the Charlie Kirk Suspension Scandal

By December 2025, the late-night wars no longer feel like entertainment journalism — they feel like political reporting. And Jimmy…

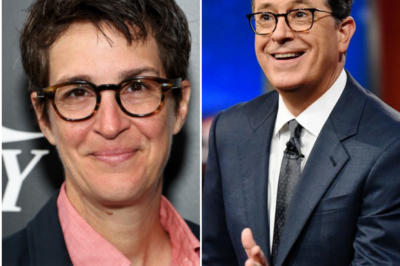

CH1 Rachel Maddow vs. Paramount: Inside the Brewing Media War Over Stephen Colbert’s Firing — and the Future of CBS News

December 2025 — Rachel Maddow has never been one to step lightly into a political firestorm. But this time, she…

End of content

No more pages to load