THE MAN WHO SAVED AN ARMY WITH A RULE BREAK

At 8:15 a.m., December 7th, 1944, in the frozen tomb of the Hürtgen Forest, Corporal James “Red” Sullivan stared down the length of a weapon that had just signed his death warrant.

An M1 Garand, the greatest battle rifle ever devised, the pride of American industry, the symbol of the infantryman’s superiority —

was a dead lump of steel in his hands.

The bolt would not move.

The trigger would not pull.

The action was fused by a chemical cement of oil, carbon, and cold.

Forty yards ahead, nine German infantrymen moved through the pines with the methodical patience of men who knew they had already won.

Their Kar98k bolt-actions worked perfectly in winter moisture — weapons designed in 1898 that, on this morning, were technologically superior to the best rifle America had ever built.

Sullivan’s squadmates were dying around him.

He had no grenades.

No sidearm.

Just a frozen rifle.

And yet, in the next 48 hours, this same broken weapon —

the rifle he was holding like a cursed object —

would kill every one of those Germans, ignite an underground revolution in weapons maintenance, and save hundreds of American lives.

Not because the rifle changed.

Because one man dared to break the rules.

THE BOY WHO UNDERSTOOD METAL BETTER THAN THE ARMY

James Sullivan grew up in Butte, Montana, a mining town where every man learned the physics of cold the hard way.

His father, a copper miner, came home each night covered in rock dust and coughing up the slow, bloody death that claimed miners before they reached old age.

Red swore he’d never go underground.

So he became a mechanic instead.

Montana winters taught him truths no classroom ever could:

Oil thickens in cold.

Carbon hardens into stone.

Steel contracts.

Machines fail the instant you trust the wrong lubricant.

When he enlisted in 1942, the Army gave him an M1 Garand and a maintenance manual written by men who had never seen what cold does to machinery.

The manual insisted:

“Lubricating Oil, Preservative, Light (LP) — Works in All Temperatures.”

It didn’t.

It killed men.

THE FOREST THAT ATE DIVISIONS

By November 1944, the Hürtgen Forest had become the U.S. Army’s bleeding wound —

70 square miles of freezing mud, sleet, rain, and death, where 31% of a division could evaporate in a week.

The 28th Infantry Division went in with 14,000 men.

They came out with 6,000.

Not all were killed by the enemy.

An unspoken percentage —

a horrifying, rising percentage —

died because their rifles seized.

LP lubricant, when mixed with water and carbon, became a black paste that froze the firing pin, locked the bolt, seized the gas system, and turned the greatest rifle in the world into a coffin handle.

Red watched it happen:

Private Eddie Harmon, 19, died working a frozen bolt.

Corporal Mike Delaney died with a jammed op rod.

Three more choked on their own blood while pounding uselessly on dead rifles.

A 14% weapons-failure casualty rate.

One in seven riflemen dying because a lubricant specification written in an office thousands of miles away was wrong.

Red tried to tell his sergeant.

He tried to tell the armorer.

He was told:

“The manual says LP oil works in all temperatures.”

“Clean your rifle better.”

“Don’t question Army Ordnance.”

He watched more men die.

Something inside him snapped.

THE NIGHT THE RULES BROKE

December 5th, 1:30 a.m.

Inside a shattered barn, Red Sullivan worked alone by the glow of a shielded candle.

Outside, sleet came sideways.

Inside, his rifle lay disassembled on a wooden crate.

He scraped away every speck of carbon.

Every smear of LP oil.

Every particle of the sludge killing his friends.

Then he did the unthinkable.

He dipped a rag into 10-weight automotive motor oil —

the kind he used in Montana winters —

and applied a microscopic film to the weapon’s moving parts.

It was forbidden.

Not discouraged — forbidden.

This was court-martial level.

Destroying government property.

Unauthorized alteration of weapon systems.

If the rifle exploded, he’d go to Leavenworth.

If he told the others and was wrong, men would die.

If he kept it secret and was right, men would die.

He chose the only option a mechanic with a conscience could choose:

He trusted physics over paperwork.

THE FIGHT THAT PROVED HIM RIGHT

December 7th, 8:15 a.m.

Nine Germans advanced through the pines.

Sullivan’s squad was four men with functional rifles — in theory — and one crippled rifleman.

Jennings’ M1 fired once and died.

Garcia’s fired three times and seized.

Rodriguez was already wounded.

It was over.

Until Sullivan fired.

One shot.

Two.

Three.

No hesitation.

No grinding.

No paste.

No freeze.

His Garand ran like a living thing.

23 rounds in 40 seconds, in freezing sleet, in catastrophic moisture, in the worst possible conditions.

Five Germans fell.

Three fled bleeding.

One crawled away.

His squad survived because one rifle among them worked.

And that rifle worked because one corporal knew the cold better than the Army did.

THE SECRET SPREADS

Word traveled faster than shrapnel in the trenches.

By evening, men were coming to Sullivan in the dark whispering:

“Show me.”

“Teach me.”

“Don’t tell the armorer.”

He taught them all.

Strip the rifle dry.

Scrape carbon like a surgeon.

Apply motor oil — not LP — in the thinnest film imaginable.

By the next morning, 15 rifles in B Company were running flawlessly.

By the next week, an entire battalion.

By Christmas, half the division.

When the brass tried to track the culprit, every man said:

“I heard it from someone else.”

Nobody betrayed him.

Because everybody who lived because of that trick knew the truth:

The rulebook was killing them.

The rulebreaker was saving them.

THE ENGINEERS FINALLY CATCH UP

By January 1945, malfunction rates dropped from 14% to 3%.

A 78% reduction.

Aberdeen Proving Ground finally tested motor oil.

Their conclusion?

“Superior to LP lubricant in cold-wet conditions.”

Soldiers already knew.

THE WAR ENDS — THE MAN FADES

Red Sullivan never told anyone.

Not his wife, not his kids, not the garage owner he worked for.

He turned wrenches in Butte.

Raised three children.

Got calls every December 7th from the few men who remembered.

He died under a car lift in 1987.

Heart attack.

Age 65.

His obituary never mentioned the rifle.

The army never thanked him.

History never recorded him.

Until a historian opened his footlocker in 2003 and found a notebook:

A hand-drawn diagram of an M1 Garand.

Lubrication points marked.

One note beside the gas cylinder:

“Use motor oil. LP freezes.”

THE TRUTH ABOUT WAR AND INNOVATION

The official Army explanation still says:

“Field modifications by multiple units improved reliability.”

That’s technically true.

Here’s the real truth:

One man from Butte, Montana saved hundreds of lives because:

He knew winter.

He knew metal.

He knew bureaucracy wouldn’t save him.

He refused to let another man die with a jammed rifle in his hands.

He didn’t do it for medals.

He didn’t do it for recognition.

He didn’t do it for glory.

He did it because someone had to,

and no one else was willing.

That’s how real innovation happens.

Not in labs.

Not in manuals.

Not in committee meetings.

In the dark, in the cold, with dead friends in the mud,

and one man saying,

“Not again. Not on my watch.”

News

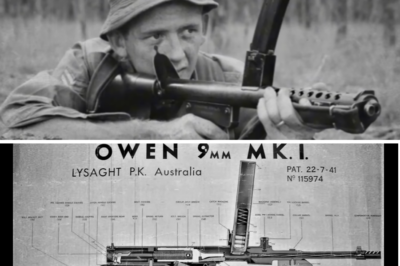

Australia’s “Ugly” Gun That Proved Deadlier Than Any Allied Weapon in the Jungle

THE GUN BUILT IN A GARAGE — THE LEGEND OF EVELYN OWEN Australia, 1939–1945A story written in the exact narrative…

German POWs Couldn’t Believe American Farmers Had 3 Tractors Each

THE PRISONER AND THE TRACTOR How a German POW in Minnesota Discovered the Lie That Built the Third Reich —…

How One ‘Inexperienced’ U.S. Black Division Turned Japanese Patrols Into Surrenders (1944–45)

THE HUNT FOR THE LAST SAMURAI The 93rd Infantry Division, the Blue Helmets America Tried to Hide — and the…

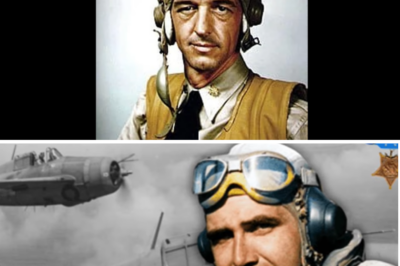

They Grounded Him for Being “Too Old” — Then He Shot Down 27 Fighters in One Week

THE OLD MAN AND THE SKY THAT TRIED TO KILL HIM Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Thach and the Seven Days That…

Germans Laughed at This ‘Legless Pilot’ — Until He Destroyed 21 of Their Fighters

THE MAN WHO SHOULDN’T HAVE FLOWN — AND FLEW ANYWAY Douglas Bader and the Day Tin Legs Met the Luftwaffe…

Why Nimitz Refused To Enter MacArthur’s Pacific War Office – The Island Campaign Insult

THE EMPTY CHAIR IN BRISBANE How Two Men Won a War Together by Never Sitting in the Same Room The…

End of content

No more pages to load