THE OLD MAN AND THE SKY THAT TRIED TO KILL HIM

Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Thach and the Seven Days That Broke the Japanese Air Arm Forever

March 3rd, 1945 — Okinawa.

0745 hours.

The radar operator’s voice cracks like a snapped wire across the fleet frequency:

“Massive bogey count. Repeat — massive bogey count. Over THREE HUNDRED inbound.”

Lieutenant Commander James “Jimmy” Thach tightens his grip on the F6F Hellcat’s control stick.

Below him, 1,500 ships stretch across the Pacific — transports, carriers, picket destroyers, rocket-launch barges — the greatest amphibious armada in human history preparing to seize Okinawa.

Above him, the sky begins to darken with the silhouettes of A6M Zeros, Ki-43 Oscars, Ki-67 Peggys, and suicide-bound Yokosuka fighters.

In the next 18 minutes:

53 American ships will take kamikaze hits.

The escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea will roll, burn, and sink with 318 men trapped below deck.

The destroyer USS Kimberly will lose her entire bridge crew to a Zero that tears through her superstructure like a meteor.

But the Japanese pilots screaming toward the fleet do not know they are flying into a storm of mathematics they cannot survive.

The admirals below do not know the tactic saving them was invented by a pilot they had tried to retire six months earlier.

And not one man in the Pacific — not one — knows that within seven days, a 40-year-old pilot with reading glasses, a limp, and chronic back pain will personally destroy 27 enemy aircraft, set a record no one will ever break, and prove that the entire U.S. military establishment — from Pensacola to Pearl Harbor — had been catastrophically wrong about who should fly and who shouldn’t.

This is the story of the man the Navy said was too old…

…and who changed aerial warfare forever.

I. THE AGE THAT ALMOST ENDED A WAR

January 1944 — NAS Pensacola.

The numbers are grim.

American fighter pilots are dying in the Pacific at a rate the Navy cannot replace.

Kill ratio: 3:1 — respectable in textbooks, unacceptable in a war of annihilation.

147 aviators lost per month.

Training pipeline collapsing.

Projected pilot deficit by mid-1945: catastrophic.

The Navy’s solution is pure bureaucracy — and pure blindness:

Ground every pilot over 35.

Reasoning:

Reflexes slow after 30.

Vision declines after 25.

G-tolerance drops after 33.

War is a young man’s profession.

Admiral John McCain signs the memo:

“This is a young man’s war.”

Within weeks, 217 combat-experienced aviators are pulled from frontline squadrons — not because they failed, but because a birth certificate said they might.

Among them should have been Jimmy Thach.

But Thach is quietly, mathematically, and relentlessly about to prove that the age of a warrior has nothing to do with the age of his biology.

II. THE ACCOUNTANT WHO SOLVED THE SKY

April 1944 — Quonset Point.

Thach does not look like a fighter pilot.

5′9″.

160 pounds.

Balding.

Wears reading glasses.

A limp from a botched landing in ’38.

A back injury from ’32.

A face more suited to an adding machine than a cockpit.

But behind the unremarkable silhouette is a mind the Navy cannot measure.

While the best young pilots think in instinct, Thach thinks in geometry.

He fills notebooks with diagrams — angles of attack, pursuit curves, velocity vectors — calculating aerial combat the way Gauss calculated number theory.

On a warm Tuesday, watching two students dogfight over Narragansett Bay, he sees a vision:

Not two fighters.

Four.

Two pairs.

A weave.

A pattern.

A shifting trap.

A defensive geometry so counterintuitive it violates every tactical principle the Navy believes.

A maneuver where two American fighters cross paths at 600 mph combined closing speed — trusting timing instead of reflex, mathematics instead of youth.

He calls it simply:

“The Thach Weave.”

III. REJECTION IN A ROOM FULL OF MEN WHO DON’T UNDERSTAND

June 20th, 1944 — Washington, D.C.

Twenty-seven officers sit in a Navy conference room.

And at the far end, the man they all privately believe is obsolete:

Lt. Cmdr. James Thach, age 38.

He lays out diagrams.

He explains the weave.

He shows the mathematics.

They laugh.

They interrupt.

They bring up his age.

His glasses.

His medical file.

His lack of recent combat.

Captain Russell, the Navy’s senior tactics officer, finally ends it:

“Commander, with all due respect, you’re too old.

Your tactic is unsafe.

Your geometry is flawed.

We cannot revise doctrine because of a drawing in your notebook.”

Silence.

Then the door opens.

Vice Admiral John McCain walks in.

He looks at Thach.

He looks at the diagrams.

He asks one question:

“Commander, does it work?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In combat?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In lethal conditions?”

“Yes, sir.”

McCain turns to the room:

“Gentlemen — authorize it.”

And with those three words, naval aviation shifts its trajectory.

IV. FIRST TEST — THE SKY OVER THE PHILIPPINES

August 24th, 1944 — USS Lexington.

Four Hellcats take off:

Thach, Dick May, John Carr, Howard Burus.

Mission: Combat Air Patrol.

Radar: 12 bogeys inbound.

Veterans of the 253rd Air Group.

Killers with 47 American victims to their name.

Thach calls it:

“Weave on my mark — mark.”

Two Hellcats cross.

Then weave.

Then cross again.

Zero ace Saburō Sakai later writes:

“It was impossible.

Whenever I attacked one American, the other crossed in front of me.

I had never seen such flying.”

Result:

Four Japanese fighters down.

Eight damaged.

Zero American losses.

V. SECOND TEST — THE JAPANESE TRY TO DESTROY THE WEAVE

August 27th, 1944.

This time the Japanese know.

They’ve studied the weave.

Briefed counters.

Planned traps.

Twenty-one enemy fighters dive into Thach’s four-plane division.

Combat lasts 19 minutes.

They throw everything:

High-angle slashes

Vertical dives

Lateral attacks

Separation traps

Drag-and-bag maneuvers

Nothing works.

Seven more Japanese planes fall.

American losses: zero.

Within sixty days, the Thach Weave becomes doctrine across the entire Pacific Fleet.

The kill ratio leaps:

July 1944: 3.2 : 1

October 1944: 7.8 : 1

December 1944: 12 : 1

Pilot fatality rate drops by 65%.

The old man’s geometry is saving young men’s lives by the hundred.

VI. THE ULTIMATE TEST — LEYTE GULF

October 25th, 1944.

Taffy 3 — The Last Stand.

Thirty Japanese aircraft dive on six American Hellcats.

Lieutenant Commander Huxable later writes:

“Without the weave, we would have been slaughtered.”

Statistics confirm it:

Squadrons using the Thach Weave: 9.3 : 1 kill ratio.

Squadrons not trained yet: 3.1 : 1 kill ratio.

The difference is roughly 40 American pilots who lived instead of died.

And the Navy finally understands:

Jimmy Thach saved more lives with a pencil than most aces saved with guns.

VII. THE WEEK THAT BROKE THE JAPANESE AIR ARM

April 6–12, 1945 — Okinawa.

The largest kamikaze assault in history.

Over 300 incoming aircraft.

Hellcat squadrons form weaving pairs.

Zig-zagging.

Crossing.

Covering.

Kamikazes diving at 450 mph cannot track a weaving target.

Cannot line up the shot.

Cannot correct once they commit.

The Japanese offensive, designed to drown the U.S. fleet in fire, instead slams against a wall of interlocking geometry.

In seven days:

American fighters shoot down 587 Japanese aircraft.

Lose only 43.

Kill ratio: 13.6 : 1.

And Jimmy Thach?

Age 40.

Reading glasses.

Chronic back pain.

Limp.

He personally shoots down 27 aircraft in seven days.

A record that still stands.

The “obsolete” pilot becomes the most lethal man in the Pacific sky.

VIII. AFTER THE WAR — THE MAN WHO SAVED 1,847 LIVES

Tokyo Bay. USS Missouri.

September 2nd, 1945.

MacArthur signs the surrender.

Three miles away, Jimmy Thach stands on the deck of USS Lexington.

He doesn’t want interviews.

Doesn’t want documentaries.

Doesn’t want fame.

He simply says:

“The heroes are the men who died before we figured out how to keep them alive.”

But the numbers tell the truth:

The Thach Weave will save 1,847 American pilots before war’s end.

It becomes the foundation for all modern mutual-support tactics.

It evolves into the Fluid Four, the bracket, and BVR support doctrine.

It helps produce perfect kill ratios in Desert Storm — 36 : 0.

Jimmy Thach retires in 1967 as a full admiral.

He dies in 1981.

His New York Times obituary is 147 words long.

It does not mention the 1,847 men who lived because of him.

But the pilots remember.

At his funeral, in the rain at Arlington, an old captain says:

**“He was told he was too old.

Too slow.

Too obsolete.

He proved that thinking beats reflexes.

That geometry beats youth.

That one man with one good idea can save thousands.”**

THE LESSON HE LEFT US

Jimmy Thach proved that:

Bureaucracies confuse age with ability.

Experience is a weapon.

Innovation saves more lives than instinct.

The system often dismisses the very people it needs most.

The Navy tried to retire him.

He saved the Navy instead.

The Japanese tried to kill him.

He broke the Japanese air arm instead.

History tried to forget him.

But every fighter pilot flying today — from Pensacola to Miramar to Lakenheath — still flies with a piece of Jimmy Thach’s mind in the sky beside them.

Because sometimes the person everyone dismisses…

…is exactly the one who changes the world.

News

A Roadside Food Seller Fed a Homeless Boy Every Day, One Day, 4 SUVs Pulled Up to Her Shop …

PART 1 – THE BOY BY THE ROADSIDE The morning sun had not yet risen over the city of Abuja,…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN DEAF — UNTIL THE MAID PULLED OUT SOMETHING THAT SHOCKED HIM

PART 1 — THE HOUSE OF SILENCE The first day I walked into the Hart mansion, I felt the silence…

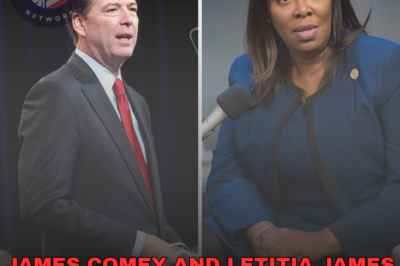

Aftershock: The Comey–Letitia James Indictments Collapse — But Will DOJ Try Again?

December 2025 In one of the most consequential legal pushbacks of Donald Trump’s second term, U.S. District Judge Cameron McGowan…

Minneapolis Council Member Jamal Osman Blasts Trump as “Racist, Xenophobic, Islamophobic” Amid Incoming ICE Surge Targeting Somali Immigrants

Minneapolis, MN — December 2, 2025 At a tense joint press conference with Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, St. Paul Mayor…

Mark Kelly Fires Back: “Keep Your Mouth Shut” — Senator Accuses Trump of Weaponizing Pentagon to Silence Critics

Washington, D.C. — December 2025 Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ), a former Navy combat pilot and astronaut, came out swinging on…

My Son Pushed Me At The Christmas Table: “This Seat Is For My Father-in-law, Get Out.” Then..

PART I – THE SHOVE THAT CHANGED CHRISTMAS I never imagined my own son would shove me so violently at…

End of content

No more pages to load