At 9:02 on the morning of February 19th, 1945, Corporal Tony Stein hit Green Beach on Iwo Jima with eighty pounds of gear on his back and a weapon his company commander had explicitly ordered him to leave on the ship.

The sand stopped him in his tracks.

It wasn’t sand the way he knew it from back home in Dayton, Ohio. It was black volcanic grit, loose and deep, swallowing boots to the ankles with every step. Marines stumbled out of the landing craft and immediately bogged down. Men fell. Some got back up. Some didn’t.

Japanese machine guns opened up from the interior of the island, line after line of tracers streaking low over the beach. Mortars started dropping in the surf. Artillery from hidden positions walked across the shoreline.

Within three hours, more than 2,400 Marines would be dead or wounded trying to push inland from that strip of ash.

Stein was one of the first men off his craft from Company A, 1st Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division. Slung across his chest was something that looked like it had crawled out of a scrap bin. To officers, it was an unauthorized monstrosity. To Tony, it was the best chance they had against what was waiting inland.

The Stinger.

He slogged forward through the sand, head low, breath burning. Twenty yards. Thirty. A man to his left spun and went down. Another Marine ahead pitched face-first into the volcanic grit and didn’t move. Stein kept running.

The first terrace was a low ridge of sand about forty yards up from the waterline. It wasn’t much, but it was the only cover between the surf and the Japanese positions. Stein dove behind it and rolled onto his knees, sucking air.

All along the terrace, Marines were pinned. Some were firing rifles in the general direction of the interior. Most were hugging the sand, trying to disappear behind nothing. The fire that was cutting them down wasn’t coming from open trenches; it was coming from concrete and rock.

About 150 yards inland, built into a rise of volcanic rock, a pillbox squatted like a concrete tumor. A narrow rectangular slit in front was the only visible opening. Inside that slit, a Japanese machine gun was stitching the beach over and over.

Stein flipped the Stinger forward and locked out the bipod.

The weapon didn’t look like anything in the Marine Corps handbook. At its core was an AN/M2 .30 caliber Browning machine gun—an aircraft gun ripped from the wing of a crashed Corsair. Attached to it was a cut-down M1 Garand stock. A bipod cobbled together from salvage steel folded under the barrel. Iron sights hand-fabricated in a jungle workshop sat on top.

It looked wrong.

It sounded right.

Tony settled the bipod into the sand, pressed the stock into his shoulder, sighted on the dark slit in the pillbox, and squeezed the trigger.

The Stinger erupted.

Twenty rounds a second poured out of the short barrel, a buzzing, ripping roar that was unlike anything any Marine on that beach had ever heard. Tracers, one out of every five rounds, etched a solid, glowing line straight into the pillbox’s face. Concrete around the firing slit chipped and spat dust.

Five seconds. Maybe a hundred rounds.

The Japanese machine gun stopped.

Nobody cheered. There was no time. Another pillbox seventy yards off to the right, built into a low terrace, was sweeping the beach with bursts. Stein swung the Stinger, realigned, and fired again. Short burst. Pause. Another burst.

The second bunker went quiet.

Marines around him glanced over, faces smeared with black sand and sweat. A couple of them called out, half incredulous, half grateful.

“What the hell you got there, Stein?”

He didn’t answer. He was already searching for the next muzzle flash.

Weeks earlier at Camp Tarawa in Hawaii, Captain Harrison Roberts had watched Stein fire this same ugly gun on a sunny training range and had seen nothing but trouble.

“What is that thing?” Roberts had demanded, walking up as Tony cleared the last belt.

“Aircraft Browning, sir,” Stein answered. “AN/M2. We pulled it from a Corsair wing on Bougainville. Modified it for ground use.”

Roberts’ lip had curled as he looked it over. It had no cooling jacket. No tripod. It ran off belts of .30 caliber ammunition, the same caliber as other Browning guns but in a configuration nobody else carried.

“It’s not issued,” Roberts said. “It’s not tested. It’s not approved. And it will not get on my ship, Corporal. You understand?”

“Yes, sir. Crystal clear.”

The thing about machinists is that “no” sounds to them like “this will be harder.”

Tony had been a tool-and-die guy in Dayton before the war, turning steel into precision under fluorescent lights. In the First Parachute Battalion on Bougainville, he’d met another machinist, Sergeant Mel Grevich from Milwaukee, and Mel had seen the same problem that Stein was now solving on Iwo Jima: Japanese fortifications could absorb too much of what the standard Marine loadout could put out.

On Bougainville, out in the jungle airstrip, a Corsair had crashed during takeoff. Salvage crews stripped the good parts. Mel walked past, saw the wing guns hanging useless in the wreckage, and stopped.

AN/M2s. Six of them. Lighter than the M1919 ground gun. Higher rate of fire. Designed to spit out twelve hundred rounds a minute from a vibrating wing.

“What if we could carry one?” he’d asked nobody in particular.

He and Private John Little, another Marine who knew how to weld in straight lines, spent their spare hours turning “what if” into “here, try this.”

They cut a broken Garand stock and grafted it onto the aircraft receiver for a shoulder mount. They stole a trigger mechanism from a Browning Automatic Rifle and rigged it to operate the solenoid-fired gun mechanically. They welded together a bipod set from scrap steel. For sights, they made a simple rear notch and front post.

The first time Grevich fired it at a captured Japanese bunker they’d dragged back for target practice, the makeshift gun made a noise like someone tearing a sheet of metal in half—very fast.

Two seconds and forty rounds later, the bunker’s front was a ragged hole.

They built six of them.

Someone started calling them “Stingers” because the guns looked like mean, buzzing things cobbled together in a fit of spite. The name stuck.

They went into combat on Bougainville, and they worked. No jams. No catastrophic parts failures. They chewed through ammunition shamefully fast, but what they hit stayed hit.

Then the parachute battalion rotated back to Tarawa, and the Stingers met Marine Corps bureaucracy.

“Unauthorized improvisation,” one exec officer had called them. “Scrap metal glued together. These will get people killed.”

Stein had argued back, which was not, generally, how you advanced your career.

“Sir, the M1919 is good, but it’s heavy. Needs a crew. Takes time. The BAR’s reliable, but it can’t put out enough in a short window. This thing gives one man the firepower of a crew-served weapon, and I can fix it if it breaks.”

It hadn’t mattered.

Regulations were regulations. Standardization made logistics possible. Every Marine carrying the same weapon meant ammo resupply, maintenance, and training stayed simple. The Stinger meant special belts, special parts, special knowledge. If Stein went down, who fixed it? Who used it?

The verdict had been clear everywhere he took it.

“Leave it behind.”

On January 27th, 1945, when the Fifth Marine Division sailed for Iwo Jima, the manifest didn’t include six Stingers.

The Marines did.

Wrapped in canvas, disassembled just enough to confuse a casual inspection, Tony’s Stinger came aboard with his gear. Somewhere between Hawaii and a black sand beach, the debate between regulations and reality was always going to end the same way.

On the ground.

Back on Green Beach, reality was screaming.

The Japanese had turned Iwo into a concrete hive. Nearly 450 pillboxes and blockhouses honeycombed with tunnels. Thirteen thousand defenders who had zero intention of dying anywhere but in place. They weren’t throwing themselves into banzai charges anymore. They were sitting in holes with overlapping fields of fire and clear arcs against the beach.

Every time a flamethrower team tried to move up, a machine gun slit chewed them apart. Every time a demolition squad crawled forward, some unseen opening stitched the ground around them.

Conventional machine guns were doing work. The M1919s were effective—but they were heavy, needed crews, needed time to set up. On a beach you couldn’t dig into, time was life.

The Stinger was something else entirely.

Stein kept moving its line of fire. He wasn’t just suppressing one bunker. He was playing whack-a-mole with a weapon that could push twenty rounds downrange in a single heartbeat. Every burst bought someone else a chance to crawl ten feet. Every pause meant scanning for the next flash.

The cost was ammo.

At twelve hundred rounds a minute, a 250-round belt vanished in about twelve seconds of sustained fire. In the first twenty minutes on the island, Stein burned through four belts. A thousand rounds gone.

He yelled over to Corporal Frank Rodriguez.

“I’m almost dry!”

Rodriguez ducked down behind the terrace, sand spitting over his helmet.

“There’s more ammo back by the beach!” he shouted back. “Supply dump! Near the water!”

“How far?”

“Eighty yards, maybe!”

Eighty yards of open sand under mortar and machine gun fire. Beyond that, the surf. No real cover.

“We need the gun!” Rodriguez added. “We can’t move without it!”

“I’ll go,” Stein said.

Rodriguez grabbed his arm.

“They’ll cut you in half out there, Tony!”

“They’ll cut all of us in half if I don’t,” Stein snapped. “Hold the gun.”

He left the Stinger with Rodriguez, slung his Garand, and went back over the terrace.

Running on that sand was like running in a nightmare about drowning. Every step sank. Every push burned your calves. Mortar rounds bracketed his path. One went off so close that a shower of black grit hit him like hail. He stumbled, caught himself, kept going.

At the waterline, Marines were already ripping open crates, dragging out belts. The “dump” was more of a churned area with stacks of ammunition, flamethrower tanks, and demolition charges under bits of tarp.

Stein grabbed two belts of .30 caliber for the Stinger—about forty pounds of weight total—looped them around his neck and shoulders, and turned.

Halfway back, he saw a man lying face down in the sand, one leg at a wrong angle, a dark stain spreading underneath him. Another Marine was crawling towards him under fire, helmet askew.

Stein veered.

He dropped the belts next to the wounded man, grabbed him under the shoulders.

“I got him,” he shouted to the crawling Marine. “Get back up there!”

Together, they hauled the wounded man up the incline to the terrace, dragging him through sand that fought every inch. A corpsman appeared, dropping to his knees with a satchel.

“You’re good!” the doc shouted. “Go!”

Stein scooped up the belts and stumbled back to where Rodriguez had the Stinger waiting.

Belt in. Feed tray down. Bolt forward.

The gun barked again.

He would do that run seven more times.

Every trip, he brought two belts forward. Every trip, he came back with at least one man on his shoulders or under his arms. Marines hit by shrapnel in both legs. A man dazed and bleeding from a shoulder wound. Two who were pinned behind a low rise with fire snapping overhead until Stein thundered in front of them and jerked them toward relative safety.

By the fifth run, Marines on the beach recognized him. A couple began pointing him toward the worst of the wounded as he passed.

“Over there! Two down by that tank trap!”

“Doc’s over this way! I’ll take the belts!”

He’d drop the ammo and change direction with whatever strength he had left.

Somebody watching all that later said it was like watching a human conveyor belt—bullets going up one way, bodies coming back the other.

All told, in those first six hours on Iwo, Tony Stein made eight runs from cover to surf and back, through what may have been the most lethal two hundred yards of sand any American ever ran. He brought back sixteen belts of ammunition—four thousand rounds—and eight wounded Marines.

In between runs, he destroyed or silenced five pillboxes with the Stinger and probably killed at least twenty Japanese soldiers manning them.

The gun never jammed.

It never melted down.

It did exactly what a man in a jungle workshop nine months earlier had built it to do.

Late that afternoon, Captain Roberts finally saw him.

Stein was half kneeling, half sitting behind a rocky outcrop, field-stripping the Stinger with bandaged fingers. The barrel was scorched but serviceable. Lava dust clung to everything. The skin on Tony’s face was raw from wind, heat, and grit.

Roberts crouched beside him.

“How many times did you run those belts today?” he asked.

“Eight, sir.”

“How many men’d you bring back?”

“Eight, sir.”

“How many of those damned boxes did you knock out?”

“Five for sure,” Stein said. “Maybe more. Hard to tell with all the smoke.”

Roberts looked at the gun.

Then back at the man.

“I was wrong,” he said quietly. “About the weapon. About you bringing it. Keep it running, Corporal. We need it.”

“Yes, sir.”

It wasn’t an official memo. It didn’t need to be. From that moment on, the Stinger wasn’t “scrap.” It was an asset.

The fight for Iwo didn’t end that day. It ground on, up ravine and ridge, into caves and across barren rock, for weeks. The beaches gave way to sulfur-smelling slopes laced with tunnels. The Stinger’s niche—medium-range suppression of fixed emplacements in open terrain—narrowed. The enemy got closer. The ground folded protection and threat together.

On February 28th, Stein went out on a patrol near Hill 362 with a rifle, not his heavy gun. An enemy machine gun started working them over. Tony flanked, attacked, helped silence it. He caught a couple of bullets for his trouble. A shoulder wound sent him back to the aid station. Doctors told him to rest.

He didn’t.

The next morning, March 1st, he strapped his bandaged arm back into a sling, grabbed his gear, and rejoined Company A. When his platoon was tasked to scout machine gun positions near Hill 362, he took nineteen men forward.

Somewhere out among the broken rock and scrub, a Japanese position opened up at fifty yards.

Two Marines went down immediately.

They were in a kill zone.

Stein told the patrol to stay low and fire. He would go for the wounded.

He crawled out under fire, reached the first man, started pulling him back.

Somewhere in that desperate ground between cover and exposure, Japanese bullets found him.

He was dead within minutes.

He was twenty-three.

Eleven days earlier he’d been a machinist from Dayton with “zero confirmed kills” and a weapon no officer wanted near his company. In those eleven days, he’d executed more raw courage than most men are asked to find in a lifetime.

The patrol dragged him and the wounded back. They recovered the Stinger.

Later, it went back to Hawaii with his effects. Eventually it disappeared into storage and then into history’s footnotes—one of six handmade guns built in a jungle and carried across an ocean because one man believed he might need more than the manual said he was allowed.

On February 19th, 1946, in the Ohio Statehouse, a Navy admiral presented a blue-ribboned medal to a young widow in a hat.

The Medal of Honor citation described the man she’d married as “conspicuously gallant.” It mentioned “a personally improvised aircraft type weapon” and “eight trips across open sand under heavy enemy fire to bring ammunition and rescue wounded comrades.”

It did not mention a machinist named Mel Grevich or a helper named John Little. It did not mention arguments in offices at Camp Tarawa or regulations that almost left the Stinger rusting in a base scrap yard.

Those details weren’t the point of a Medal of Honor.

The point was that when everything went wrong on that beach, when plans met concrete, someone had been there with the right tool and the will to use it.

Today, most people driving past Calvary Cemetery in Dayton have no idea who lies under the simple white stone with the small Medal of Honor emblem etched near his name.

Most Marines can tell you about the flag on Mount Suribachi.

Very few can tell you about a kid from Ohio who dragged eight men off a killing ground and tore five machine gun slits open with a gun he wasn’t supposed to have.

The story of the Stinger sits at an uncomfortable intersection the military still wrestles with: between standardization and innovation, between regulations and reality.

Armies run on common calibers, shared parts, known procedures. That makes sense. It keeps logistics sane and training unified.

But wars are lost—and won—in gaps. In those moments when what you have doesn’t quite match what you need.

Sometimes, closing those gaps requires someone like Grevich to look at a wing gun and see a shoulder weapon.

Sometimes it requires someone like Stein to hear an order and decide, quietly, not to obey it.

That’s messy.

It’s also human.

In a perfect system, there would have been a committee, a prototype program, tests, field trials, a formal designation for a high-rate-of-fire portable machine gun for bunker busting. Maybe by 1947, they’d have had one.

In the system we actually had, there was a wrecked Corsair, a welding torch, and a machinist with an idea.

And on February 19th, 1945, there was black sand, concrete, and a company of Marines who needed that idea to be real.

The next war won’t be fought with welded aircraft guns on rifle stocks. It’ll involve drones, code, satellites—tools that make a Stinger look quaint.

But the underlying question won’t change.

When what’s issued doesn’t match what’s needed, will there be room for someone on the ground to look at what’s possible and say, “We can do better than this”?

And will there be someone willing to carry that better thing into fire, even when everyone tells him he’s wrong?

Tony Stein was.

That’s why he matters.

News

Alina Habba Resigns as U.S. Attorney for New Jersey After Court Battle Over Her Appointment

NEW JERSEY — After months of legal turmoil and mounting judicial backlash, Alina Habba has stepped down as Acting U.S….

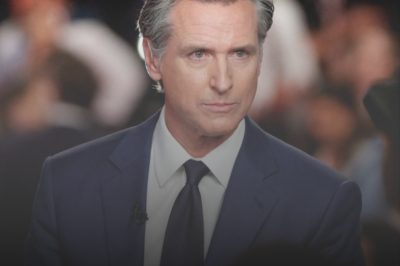

A Balanced Look at Governor Gavin Newsom’s Record: Ambition, Achievements, and a California Divided

California Governor Gavin Newsom has long been framed as one of America’s most charismatic political figures—an image reinforced by his…

Candace Owens: How a Once-Obscure Commentator Became the Most Dangerous Woman on the Internet

By the time Candace Owens began publicly insisting that French president Emmanuel Macron and his wife Brigitte were part of…

Inside the Minnesota Social Services Fraud Scandal: A Billion-Dollar Breakdown, Retaliation Claims, and a Growing National Ripple Effect

The Minnesota social services fraud scandal — now estimated at nearly $1 billion in stolen taxpayer funds — has exploded…

ABC Extends Jimmy Kimmel’s Contract Through 2027 After Turbulent Saga Over Charlie Kirk Comments

ABC has renewed Jimmy Kimmel’s contract for another year—extending the late-night host’s tenure through May 2027—following what insiders describe as…

Greg Abbott Makes Major Announcement About Turning Point USA in Texas, Warns Schools Against Blocking ‘Club America’

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott on Monday issued his strongest endorsement yet of Turning Point USA’s (TPUSA) high school network —…

End of content

No more pages to load